From making violence visible, to taking responsibility and organizing avenues for reparation

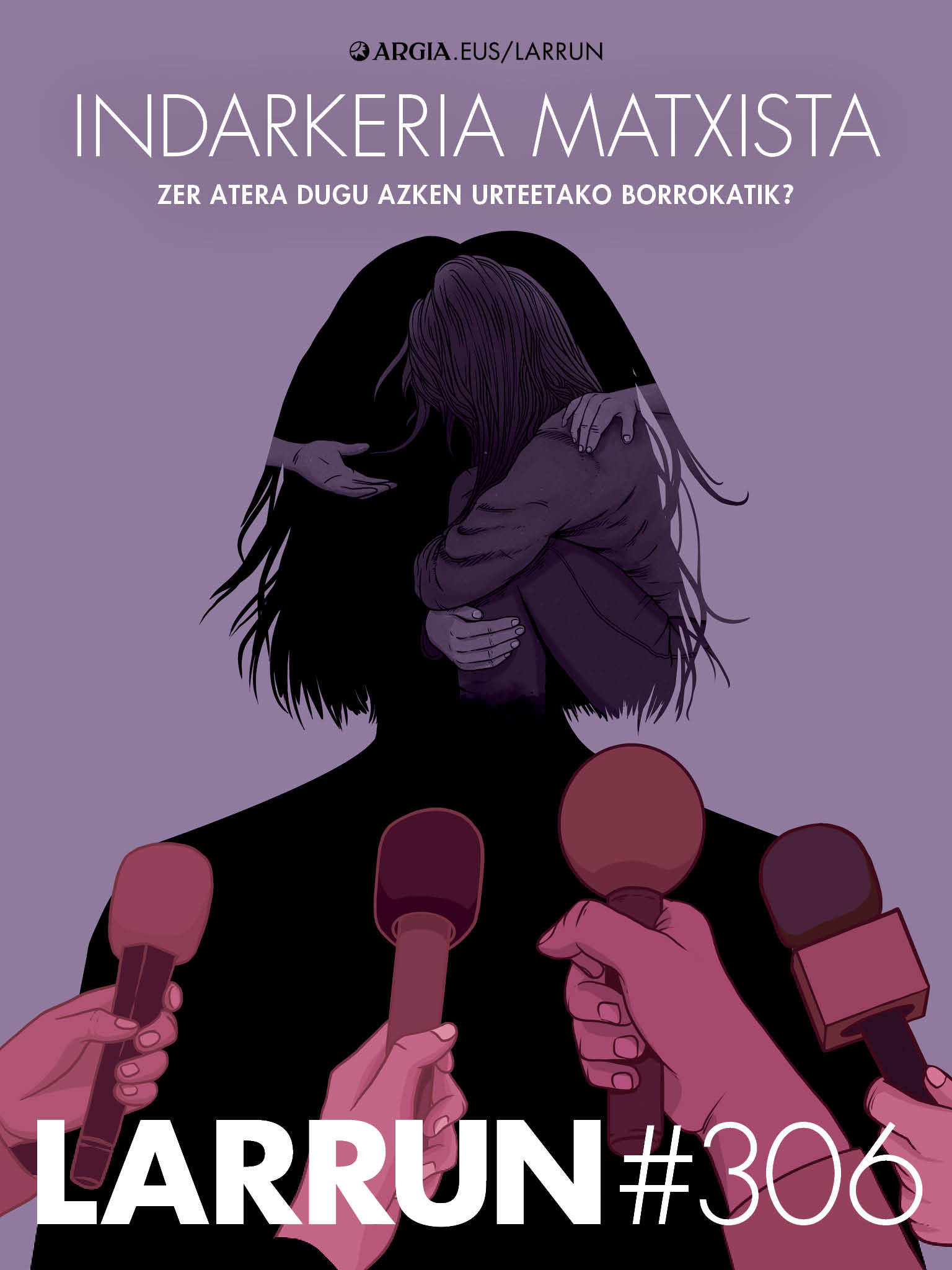

- In the last two decades the issue of macho violence has been brought to the forefront by the struggle of the feminist movement, among other things, and what was described as intimate partner violence or a “family problem” has jumped into the public sphere and onto the streets. The wave against male violence has been strong: it has become visible, women have taken to the streets, men have been questioned and it has been highlighted as a structural problem. In a few years new and theoretically more advanced laws have been established. But what was the point of that? Have the judicial processes done well? Is the community willing to accept the magnitude of the problem? When will the men take care of it? What trace did the wave leave?

At a time when the wave of the street is calming and capitalism is emptying itself of feminism, women continue to try different paths: feminist justice, community processes, social media denunciations... Idoia Arraiza Emagin, a member of the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz, Alejandra Codesal and the lawyer of the Garazi Plazaola Irule Abogados group, have reflected on the possibilities and limitations of all of them and on the path taken. It is clear to them that the focus should be on reparation for the person who has suffered violence and the response to the macho violence should be based on collective responsibility.

In recent years there has been an increase in the number of complaints and a deepening of the judicial process. What did it do for? What limits does it have?

THE PLAZA GARAZI: In the initial blow, I am surprised that you mention that the percentage of complaints is increasing. It is true that, given the data and statistics, the trend seems to be on the rise. But the experience of Irule shows us that the highest percentage of macho violence is not reported, nor is it judicialized. The data confirm our feeling: if we compare the amount of gender-based violence according to the surveys and the number of complaints, we can conclude that only 5.7%-6% are reported. The reason for the increase in denunciations may be that today women are identifying violence in a much more concrete way, as well as gaining legitimacy to denounce it, thanks, among other things, to the work of the feminist movement in recent years.

With regard to the legislative framework, progress has been made. In 2004, the Comprehensive Law against Gender Violence was enacted in the Spanish State, and the previous context was very different. I would only insist on the “yes” law (2022) because this has also led to a series of instruments that help to deepen the judicial process, even outside the judicial process.

But we see many limitations in the judicial process. The lawyers, judges, prosecutors or legal operators concerned lack training and training in the gender perspective. It is not just that they need to cultivate awareness and technical knowledge in gender-based crimes, but that they need to understand the structural root cause of macho violence and how it affects each case. We must demand this training, which was already partly covered by the 2004 law.

Another limitation is that access to justice is not universal: the system of free justice, which is absolutely necessary, is in failure. It is very precarious and we constantly see how women treated by court-appointed lawyers often have bad experiences.

On the other hand, judicial processes reduce the conflict of violence to the relationship between the woman who has suffered violence and the person who caused it. In the courts it is not treated as a structural problem, although in the laws there is this political recognition that places it as structural violence and within the patriarchal system. If we deny the very root of the conflict, the judicial process does not have sufficient potential to address the damage and the underlying conflict. By this I do not mean that it is useless; we need the tools to avoid impunity. After all, we can fall into the judicial system at any time for anyone, and even more for the most vulnerable people. In this context we experience a terrible violence every day, and many women need this tool, even if we do not want to meet the needs that we would like to meet, because it is a way to guarantee a minimum of security and well-being.

How do you assess the course of the judicial process? Do the limitations it has cause it not to be denounced more times?

ABOUT IDOIA ARRAIZA: I do not know the judicial system so intimately, but from my experience I say that about ten years ago the slogan was denounced, denounced, denounced, as if it were a salvation for women; and we have seen that this path is not valid. One of the last years has been the learning, the limits of the judicial process have been socialized. Before it was something very unknown for us, we weren’t trusted by the courts, but today we see it live because of the leaked videos-and, what phrases they throw out, how it revictimizes... It's very hard to go through this process, you have to be strong.

In my view, the main limitation is that the resolution focuses on the punishment of the perpetrator and not on the reparation of the perpetrator. This paradigm is very limited and individualizing. What women need often does not correspond at all to what the judicial system offers. Moreover, in this process they are also subjected to institutional violence, the word of women is questioned and they are made to feel guilty.

It is the war of the Rapporteur that is at stake in the assas, it seems that if the verdict is in your favor you can say “mine was true”. They demand objective evidence for this, but sometimes this is very difficult. Many cases are dismissed for lack of evidence, without ruling on whether the defendant is guilty or innocent, but since he has not been convicted, he is used to say that the woman was lying and is sued. Winning the trial has more to do with winning support in the Rapporteur’s war than feeling that justice has actually been done or that you have received reparation.

THE PLAZAOLA: The judicial process is paternalistic, and the feeling of women is that of losing the agency, of infantilization: they have the frustration of expectations, it does not correspond to their times, it is difficult to place their word there... Due to the lack of capacity of legal operators and the macho culture – which is the same as in society – the imaginary generated by stereotypes and prejudices leads to a mistaken look at women: they are seen as irrational, crazy, unequal people, among other things, because of the effects that the process itself generates on women. The process requires women to be perfectly coherent, chronologically perfect... and just in macho violence this does not happen.

It often happens that, out of embarrassment or for certain reasons, women minimize or justify violence, and then they are not believed. It is directly related to the stereotype of the “real victim”; the “perfect victim” is: a woman who has suffered violence but does not report it, who has an attitude of submission and passivity, who has suffered very serious or deadly violence... But the reality is that almost no one fulfills this stereotype, since the profile of women who have faced violence is varied. In addition, in this imaginary it is also understood that in our society machismo is already overcome, and it is believed that women use judicial processes to generate harm to the aggressor; the false accusation or what we call spurious encouragement is present.

A judicial process is initiated on all this imaginary. So, of course, many women choose not to report it because they generally look at the court with mistrust as something they can’t control. What results can we achieve with the process? The main result could be punishment, but this woman probably wants protection, to stop violence, to improve living conditions... the result does not correspond to her needs. After all, the justice system is patriarchal and reproduces violence. We can see the law as something neutral, abstract and universal, but this legal framework has been made by white, straight, middle-class or upper-class men. This is the subject or recipient upon which the law is based; women and other identities are on the margins; the law is not intended for them.

Should we continue working to make progress in the justice system or should we focus our energy on other avenues? If it is to be continued, what are the areas to be addressed?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: We are committed to other ways without hesitation. This does not mean that the judicial route should not be a line of struggle; it is perfectly legitimate to want to use it. It is another tool that can be useful for some women, so it is worth improving and working towards it. It is true that some progress has been made, It is only true that the law is yes, for example. We can criticize that it has both pros and cons, but it has been achieved thanks to the struggle of the feminist movement and deserves recognition.

What improvements in the legal field? Issues such as: understanding violence within public power relations, not questioning the women’s narrative, focusing on the needs of each woman for reparation, having all this look internalized by all those involved in judicial processes... And the logic that more prison sentences will lead to less violence must also be changed. What women often want is not to repeat it, so what elaboration or tool will be proposed to this man?

THE PLAZAOLA: Of course, there are other ways to go. However, the focus should not be shifted away from this, but efficiency must be improved and institutional violence must be resolved. The humanization of the judicial system and the application of a gender perspective is both necessary and urgent. Putting the body in the courts is very hard, it is also hard for us as professionals. The atmosphere, the looks, the comments, this constant questioning... they treat women as if they were a cold procedure.

When we talk about sexist violence, we talk about criminal proceedings, but I would like to remind you that there is an area that is more unknown: civil proceedings or family proceedings. This path is also very violent. Many cases of violence are not reported and are dealt with in the form of divorce and parenting measures by civil or family judges. There are legal instruments in this process that allow measures to be taken, for example in the case of child care, if they are in a situation of violence by their father. We claim the resources received by the laws, but the judges do not take them into account, they do not have a gender perspective. There is very quiet violence in civil processes, we see very violent cases. Many judges, prosecutors, and/or attorneys do not identify that what they are seeing is violence, and it is urgent to change it. Shared parenthood is having a huge impact on children and families, as violence is perpetuated in many cases. This line must also be strengthened.

I see some changes that are feasible. For example, using an easy-to-read system in sentences, not cryptic language. Sentences must be read by any person who is not an expert in law. The right to carry out the process in Basque must also be guaranteed. Law is, or should be, a social service and should be socially oriented.

Another change would be to put people who have suffered harm and their needs above bureaucratization. For example, in the case of sexual assault, which is a semi-public offence, the general rule is that the woman who has been assaulted must decide whether or not to file a complaint. But this will is once again ignored by institutional violence. Even if the trial has already begun, the prosecutor and the judges should understand that the person concerned has the right to withdraw.

How do you evaluate the legal framework, of the Spanish State? What progress has been made? What are the boundaries?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: I would mention two laws at the state level. One, that of gender-based violence in 2004, is very limited: it limits gender-based violence to aggression by a partner or ex-partner, i.e. the private sphere. It is true that the autonomous laws exceed the state law, in the Basque Country it is identified that violence against women is suffered in any sphere, and several types are contemplated. Institutional violence and torture have been added to the latest reform of the law among the forms of macho violence against women. At least there's progress on paper, then in practice, well.

The other, Just yes is the law, there is a step forward, at least in theory and location; the focus is to value approval. And it calls everything sexual assault, that's something we've fought for since the feminist movement. This has also been criticized, but I think there are two controversies: one is to call everything an attack, and the other is to see if everything has to go through the penal code. Other things are criticisable, and although everything is very nice in the law, then many issues remain in the hands of the judge’s interpretation.

But it must be acknowledged that progress has been made on paper and in preventive measures. Thanks to this law, comprehensive crisis centres have been set up in various autonomous communities to deal with sexual assaults, institutional resources that you can use free of charge even without making a complaint, offering legal and psychological advice, etc. Another thing is what employees are in these centers and what treatment there is... the same as always.

THE PLAZAOLA: It also seems to me that the legal framework of the state is quite apparent, given the context in which we live. The 2004 Act did not even comply with the Istanbul Convention on Violence against Women, but It is only Affirmative that the Act has broadened the framework and the subject, and in some way equated rights in the case of sexual assault with those who suffer from intimate partner violence. Since the issue of consent has been included in the criminal type, we can begin to use another discourse in the courts. The Organic Law for the Full Protection of Children and Adolescents (LOPIVI, 2021) is also noteworthy because it has brought new concepts such as vicarious violence and parental alienation syndrome. It seems to me that these are truly courageous laws that provide practical tools, even useful for the judicial field; they have great potential.

I think they have done a powerful exercise to see the reality and to say that women do not resort to the judicial system, we also need other measures. That is why they have also included elements that are outside the judicial process, such as crisis centres, the right to receive evidence even without making a complaint, etc.

Another tool is the so-called pre-test. In reality, for women who have been sexually assaulted, this measure is enshrined in the Victim’s Statute, but in practice it is not done because neither the spaces nor the professionals are oriented to it; now, in LOPIVI it has been recognized that it is necessary to carry out tests in advance for those up to 14 years old, but we will see how they will do it. Compliance with this measure could reduce re-victimization, because it means that the statement is taken only once, through trained professionals, and that you will not have to repeat the story again.

Is it necessary to define what violence is? Should all forms of macho violence be prosecuted?

BY ALEJANDRA CODESAL: The self-criticism or reflection that we have made in the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz in the debate to determine what violence is is is that we cannot simply count the attacks. In order to draw attention to the importance of violence, we have often numbered attacks without contextualizing them. In this way it was sought to add to the table the breadth of violence. But today it is up to us to think of new formulas: talking about attacks of higher and lower intensity is not about downplaying violence, for example. Addressing the intensity of violence can have a political role and help us to frame different forms of violence without falling into alarmism or a culture of fear. All sectors have a responsibility to do this, and it is also the job of the media to give structural character to the attacks.

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: All violence must be named because what is not named does not exist. When we talk about direct violence, it is important to understand that sexual assaults, for example, are not specific and isolated cases, but occur due to the presence of structural violence. Structural violence is based on the economic, material and unequal distribution of power. Without forgetting the symbolic and cultural violence.

This does not mean that all violence must be judicialized, because in the first place, it is impossible. But we need solutions to all kinds of violence. First they must be made visible and then we need tools to stop them and not repeat them as much as possible. Women want the recognition of the pain they have been subjected to and the guarantee that it will not happen again. It is clear to us that the tightening of the criminal system will not end violence. Prisons do not serve for social change; on the contrary, they serve to strengthen the values of the patriarchal system.

THE PLAZAOLA: The feminist movement has worked hard to name violence, which makes it easier for one to identify. However, judicializing everything would not make much sense, the system would collapse. I think it makes sense to use the criminal code only for the most serious cases. In reality, it is the minority that chooses the judicial route, so the solution must be somewhere else.

In addition to the judicial system, a number of other avenues have been explored to combat gender-based violence. What are these paths and where are we now? How do you value them?

FROM CODESAL: Feminist self-defense is the tool that we proclaim from the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz, and we have always placed it outside the penal system. We do not say whether or not it is legitimate to use the judicial system; however, we believe that attacks occur in specific contexts, in the community, and that we should therefore address them in the community. We have been defining what feminist self-defense is and we continue to do so, walking. We make a great reference to networks of support, to collective attention, to the transformation of spaces into feminists... To do this, we are working on the formation of protocols and we focus on three areas: pedagogy, prevention and response.

We usually associate the protocol with the immediate response in the event of an attack, quickly and automatically. But it is not only that: the protocol must offer a feminist image, and experience has shown us that the very existence of the protocol can have a preventive function, although it does not mean that the attacks will not exist. The protocols are not only for party spaces, but they show that this space considers itself feminist, that it will provide some guarantees to have the safest possible area, and that it should ensure that if someone feels that they have been attacked, they will have a network of protection, among other things. They must have a broad vision, because we have seen that the protocols focused on the response have many limitations: the risk of falling into automatism, not taking into account the word and will of the aggressor for following the protocol in detail... In the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz we have learned how to change processes and promote debates and reflections.

Care must be a collective responsibility. If there are several groups in a space and the feminist movement is involved, it is not only our task to create protocols and turn the space into a feminist. We must also call upon the responsibility of cishetic men, because often the aggressors are around them and can play a preventive role. The discussion that we have on the table is what to do when the attack occurs; often men neglect the perpetrator because they do not want to identify with him. But the goal is not to move from one place to another. The environment must also have a function in the repair, it must perform accompaniment.

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: I will highlight three paths: feminist self-defense, anonymous denunciations and other community models of justice. The most anonymous complaint is in full swing, and it seems to me that dynamics such as Me too can be another way of making a social complaint, outside the judicial channel. Then we can discuss what the opportunities and limitations are and what all this entails.

In the case of other community justice models, we are already working on how to handle attacks when they occur within an association or collective. How to make a comprehensive process by putting the person who has been attacked and their needs at the center. For example, in order for this person to continue his or her normal life, the aggressor may not use certain spaces, nor may he or she be a cultural and political reference. In the meantime, the aggressor will be asked to cultivate, to take responsibility; the ultimate goal will be for this person to really have a transformation, and to be able to return to life, to spaces, if there has been reparation. It is true that these processes require certain conditions and are rarely carried out, but it is another possibility that is bearing fruit in different places. They are parallel models of justice, made from transformative justice.

THE PLAZAOLA: I knew all these paths of care and I find them very interesting. Those of you who are working on it know that it is not an easy topic, and you can not idealize it or lose its criticality. But in this process of construction we can feed each other and extract very interesting studies that we can also apply to the judicial system. We need to work these other ways as well.

The feminist movement advocates a feminist model of justice. What is it and how is it done? What has the application shown in recent years?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: Feminist justice is a concept that is under construction, both in theory and in practice. Theoretically, I would say that feminist justice is based on restorative justice, it focuses on reparation: that of the person attacked, of the relationships, of the community. It is understood that if both parties make a commitment, it is possible to resolve the situation. And transformative justice tries to change the previous conditions that have allowed violence, to make the transformation more integral. Feminist justice drinks from these ideas.

For me, feminist justice is justice that puts at the center the dignity and reparation of the person who has been attacked. What matters is not what is done, but with what intention. To give an example: the processes that are carried out from the community can be a way of doing feminist justice, in which the aggressor really recognizes that he has caused pain and wants to take responsibility for it. But if you do not accept this, taking other means and/or making public denunciations can also be a feminist justice if the dignity and reparation of the person who has been attacked are at the center.

FROM CODESAL: We reflected on feminist justice in January during the days of the Chaqueta de Violencia Machista organized by the World March of Women of the Basque Country, and we believe that the following three criteria mentioned there must be basic to start processes: the guarantee of non-repetition, the fight against neglect and the reparation of the affected subjects. The process varies greatly depending on the responsibility of the person who caused the pain, who sometimes only does it to maintain a good image, and it is necessary to see if it is really linked to a commitment.

In addition, it is important for us to have a connection with other sectoral struggles and to guarantee the material needs of the person. We cannot talk about feminist justice if there is no access to housing, if there is no access to decent employment, if there are no guaranteed material needs. Those who are often subjected to macho violence are the subjects beaten by other forms of violence. All this must be taken into account in the realization of feminist justice.

What is the significance of feminist justice in society today? How much effect does it have? How much is this feminist justice?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: Feminist justice is very abstract, something very powerful. I find it difficult to answer that question. The judicial system has not been chosen or resorted to feminist justice, one way or another. Feminist justice includes many things, from the philosophy of feminist self-defense to anonymous accusations. Feminists have always tried to obtain our truth, recognition and reparation with better or worse results, but from this attempt we are building feminist justice.

As far as the implementation of other community processes is concerned, I think it is carried out in very specific communities, in our politicized spaces, and it is by no means generalized in the public. It arises from a need, seeing that the other does not serve us, we are experimenting and practicing if we achieve it in this other way. With all the difficulties they have, which are very difficult and hard processes.

FROM CODESAL: Many practices that are not identified as feminist justice may be related to feminist justice. One of the requirements is that the person is not isolated and there is minimal articulation with a protective net. If the mother is the one who resists violence, for example, she can take advantage of community life to organize support: having contact with those of her children’s leisure group, with neighborhood merchants... or even having a group of friends. Even if the feminist paradigm is not in mind, the fact that these support networks are organized can be a feminist justice. We need to reflect on this, how to allow mechanisms and alliances for the existence of these networks in different contexts.

The number of complaints on social networks has increased considerably. Why did this happen now? What does he respond to? What function do they perform?

THE PLAZAOLA: I'm not sure why now, but I saw it coming. Me too from the USA, the account and book of Cristina Fallarás in the state... Women have found on social networks a much more accessible and secure way to make our stories. There is a tremendous need to make our voices heard, and this is far more effective than the path that the judicial process offers.

It has generated a lot of interest in the media, but what we say in the office is that it has not surprised us at all, it is a reflection of the violence that occurs in the day to day, a symptom, and it is very positive that it comes to light. It has great potential because it has made very visible the extent of the violence, how normalized we have it, and how close we have it. For it to evolve more transformatively, a more collective process is inevitably needed, but that would be the next step.

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: The internet and social networks have many possibilities and limitations, and this is an example. We can take that space to tell our words and our experiences, to read and see what others have done to me, to feel complicity and to encourage you to tell mine, even if it is anonymous, because it is very hard to confess to yourself that you have suffered an attack.

I also believe that there is the potential of Christ and that for some people this is the first step towards reparation. What's going on? It has become visible how big and structural the violence is, and that the macho and fascist reaction has come to delegitimize it and question our word again, as everywhere else. Even if I go to court instead of counting on social media, that’s not the solution. The public does not want to recognize how deeply the violence of patriarchy is rooted and how far the effects of its acceptance go, that is why the reaction comes. It must be a collective responsibility, because we are all involved. The attackers are not monsters, they are normal people, they can be my brother, my son, my partner... and to accept all this is very hard, we are not ready.

FROM CODESAL: It can be a way to channel pain. It is a way of being able to locate the Special Rapporteur outside the criminal justice system, in the conditions that you want and with the minimum guarantees to guide the process. It is a very new process that will still bring us many reflections; it has lights and shadows. It has the potential that you mention, but many times in the feminist movement we doubt what to do with all these denunciation messages, as if we had to attend to them. And many don’t look for it, they just need to release it, and maybe they have other mechanisms outside of social media.

It also has limitations, for us it is necessary to contextualize the attacks, and with this type of testimonies it is not so easy. We cannot forget the structural reading, otherwise the flood of testimonies can lead us to the normalization of attacks or the feeling that the feminist struggle has achieved nothing. There are many challenges to this topic, and we need to address this from the collective as well.

Another way of denouncing the macho violence is the street. Have the street protests reached their peak? Are they effective?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: I don't think they've lost their effectiveness, they've lost their impact. A few years ago, the demonstrations of March 8 and the opposition to some of the attacks were very spectacular. Now that impact is lost. However, these massive demonstrations have made an illusory effect, these photographs have not been real; it has had a lot of fashion and even capitalism has wanted to take it to enrich this wave. Now we have to see what fashion has left behind.

We have achieved several things through mobilizations, for example, they have done so in the context of protests triggered by the gang rape of San Fermin. Only yes is the law. And the wave has also brought a strong macho reaction, not only from the right, but also from the left: they put up resistance to comply with protocols, they more easily question what we have said, and we are also seeing it among young people. Now the challenge is to keep these things that we have achieved, and the street will always be efficient. The loss of impact does not mean that we should not use street protests.

FROM CODESAL: The presence in the street is essential, both for the emergence of strength and speeches that are limited to certain spaces to go out into the street. It serves to mark some red lines around some discussions. The discourse of the feminist movement will never be unified with what may be on the street, but we mark some ideas that later enter the public in street mobilizations. The current situation is the result of the struggles that have been going on for years, and it must remain so.

We understand the street taking in a literal sense: the incorporation of the feminist imaginary in the spaces, the presence of feminist messages, the creation of networks of mutual support between different struggles, the visibility of the feminist movement with which it unites. Making alliances is also about taking the street, as this guarantees that mass demonstrations, such as the general feminist strike of 2023, can take place.

THE PLAZAOLA: Almost all situations in which macho violence occurs tend to be within the family or in intimacy. Since these are realities in such a private sphere, it is absolutely necessary to make them visible, to take up space and to have these speeches, both on the networks and on the street.

How are other feminist defense mechanisms doing now, have they been weakened? Is it time to try new ways? Where do you want to go?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: We need to rethink the philosophy of feminist self-defense. In schools we see that many young women are very empowered and able to respond to their peers, for example. But it is true that many others have no internment at all and want more support and more police. The idea of delegating to the institutions and the legal system has spread, and I think we need to believe again in our ability to defend ourselves, to respond individually and collectively and to manage things differently. Feminist self-defense has been closely linked to the shooting of the attacker from the bar during the holidays, etc., but it’s not just that. Knowing that most of the attacks happen from a known person, or that some situations happen to us when we are flirting, we need intimate empowerment: to put my desire in the foreground, to set boundaries, to be able to manage those situations myself.

We're in the swell of the wave, and we're rethinking where we should go. The World March of Women’s Day in Villava was also dedicated to this, among other reasons, because we saw the need to renew tools such as the protocol. From the feminist movement we are constantly thinking about strategies and tools to combat violence, and we will continue to do so, adapting to the situation and opportunities of the moment.

FROM CODESAL: I don’t know if it’s a turning point or not, but it’s true that today the media are paying a lot of attention to the judicial process; and the guarantees are elsewhere. I also support feminist self-defense. Let me repeat: we have to organise the responses from the community and the support networks, depending on the context of each case.

I have a pretty positive outlook. The struggle has had an impact on other generations, and we see that some groups of young people have the idea of feminist self-defense in their minds, and not especially those who are organized in political movements. In basketball teams, for example, the macho attitudes of coaches or other figures are being identified, and the girls themselves initiate defense mechanisms and network to make joint complaints. However, it is true that in some sectors the idea of delegating support and/or asking for more police may be present. We will always be in this tension, constantly refining the discourse: if the feminist movement has launched a discourse and political use has been made in some sectors to increase sanctions and defend the prison, we will have to pull to remind ourselves that the feminist movement must be anti-prison and we must defend other means.

THE PLAZAOLA: We are very focused on ourselves, so where can legal operators go? What we are working hard on is adapting judicial processes to the needs of women. Experience has shown us that the way women are treated in legal processes radically changes their level of reparation. All people and workers in primary care must be trained in a gender perspective; social services, equality departments, women’s homes, crisis centers, Ericoría, courts... In Irul we try to carry out the care under the right conditions, we see that this is the path that we can improve. In the formations we try to transmit these new ways of doing.

At what point are the public institutions? What needs to be demanded of them?

FROM CODESAL: The organizations have made feminist speeches, but they have not applied them. They need to put resources not only on equality policies, but on investments in general, on the health system, on the education system, on social policies... They must guarantee material needs. We need to push from the street, from an intersectional perspective. That is why we work in alliance with other groups, because we understand our struggle not as demanding only equality policies, but as the struggle to guarantee minimum rights in the whole.

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: With the focus on macho violence, the resources that are destined for this are increased, they are not precarious for the users, the workers have decent salaries and the services offered by the institutions are not another place of re-victimization. Waiting lists for care by specialized psychologists cannot be 4-6 months, to cite one example.

THE PLAZAOLA: We must look at the issue as a primary social and political conflict, it is a serious issue, but it does not have this reflection in the budgets. Resources are needed to tackle all these paths that the law already allows; the biggest problem is that the advances remain on paper, which is of no use to us. There is political legitimacy, but the political will of the larger sector is not real. Those of us who are working on these issues, as well as those responsible for politics, see that most services have been overwhelmed for a long time and that is not enough.

In addition, we have recently observed that in the cases we attend to, the housing issue is a recurring problem, sometimes central. The lack of access to housing leads to the perpetuation of violence in any type of family and economic situation. Many women and children live in situations of violence because they cannot leave this house, otherwise the solution to stop the violence would be much faster. Housing is a very big social emergency.

FROM CODESAL: Local actors have concrete proposals and organisations have the opportunity to make progress on them. They have the opportunity to receive specific demands from domestic workers, pensioners and/or collective housing and then take steps to build a new system.

The media has become very powerful loudspeakers of sexual assault. But are we doing well? Does offering a flood of attack news have any negative consequences? How should the media act?

THE STORY OF ARRAIZA: The fact that the media is a loudspeaker and makes something visible as such is not bad, but depending on the treatment of cases, the media can be friends or enemies. Some hegemonic media and gatherings are looking for morbid and controversial ways to make money on the subject of sexual assault. All they can do is confuse things, question the word of the aggressor, give space to the aggressor and the macho speeches... it’s very harmful.

They can also have a good side if they respect certain conditions: if they place violence as a structural issue, and if they do not treat attacks as something specific. They must take advantage of specific cases to expose all this basic violence, to make them understand where it comes from, and to demand responsibility especially from the Zis men, but also from the community and society. We also need positive references, such as the cases of women defending themselves from an attack and going out on their own.

FROM CODESAL: The media that make a feminist bet should also allow spaces like today’s and give voice to other positive experiences to convey the idea that we are moving forward; how the feminist response is being organized, what good practices are used... Because the mere scrutiny of attacks can fuel a sense of hopelessness and anguish for women or other identities, and does not involve men’s questioning. We need to think about the goals with which we launch various messages and what is really more transformative. For example, seeing a flood like this can greatly paralyze a person who has suffered an attack that has had a major impact on his or her life.

THE PLAZAOLA: It is very important to treat these issues in a relaxed way, and to provide spaces for discussion from different points of view. When people call us from the media, they often ask us for instant answers and opinions, and this speed is not of interest for reflection and influence in the transformation.

It just comes to mind that yes is the noise that was created in the media with the law. I was suffering to see that there was only talk of revising the sanctions. I could not believe that the media were unable to explain the law and frame the debate: where the law came from, who did it, for what... All this must be explained by specialized people and not by the participants. It is necessary for our rapporteurs to be present in the media, we must also occupy this place, but not under any conditions.

THE MEMBERS OF THE TABLE:

Idoia Arraiza Zabalegi, member of Emagin

Born in Pamplona in 1987. She is a psychologist by study and holds a master’s degree in Feminist and Gender Studies. She has worked at the Midwife Association since 2011. She conducts research, advice and training in the field, especially in the field of macho violence and feminist self-defense: in the context of parties, raising awareness, creating protocols... It contributes to the management of cases of violence within associations and movements. From a young age she has participated in the feminist movement and in various groups.

Alejandra Codesal Celorio, member of the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz

Born in Vitoria in 1994. She is a member of the Feminist Movement of Vitoria-Gasteiz, which operates from the perspective of the popular movement. In recent years he has participated in the Working Group on Protocols, where he has worked on protocols for dealing with attacks both in the festive area and in other spaces. He has accompanied in concrete attacks and is currently organized in the Working Group on Violence. They are reflecting on what they have learned from their experiences and working on responses to violence. They collaborate with several agents of Vitoria.

Garazi Plazaola Ugarte, lawyer at the Irule office

Born in Legazpi in 1989. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Law and a Master’s degree in Human Rights and Public Authorities. He has been working as a lawyer since 2014 and is the founder and member of the Irule Abogados group. Through this office, they provide legal services from a feminist point of view, because they consider it necessary to carry out traditional legal practice in a different way. They work mainly with private cases related to domestic violence and macho violence in general, both in and out of court. They provide legal advice in women ' s homes and municipalities, as well as training on, inter alia, the contents of recent laws related to gender-based violence.

Prentsaurrekoa eskaini dute ostegun honetan Marc Aillet Baionako apezpikuak, elizbarrutiko hezkuntza katolikoko zuzendari Vincent Destaisek eta Betharramgo biktimen entzuteko egiturako partaideetarikoa den Laurent Bacho apaizak. Hitza hartzera zihoazela, momentua moztu die... [+]

Antifaxismoari buruz idatzi nahiko nuke, hori baita aurten mugimendu feministaren gaia. Alabaina, eskratxea egin diote Martxoaren 8ko bezperan euskal kazetari antifaxista eta profeminista bati.

Gizonak bere lehenengo liburua aurkeztu du Madrilen bi kazetari ospetsuk... [+]

11 adin txikikori sexu erasoak egiteagatik 85 urteko kartzela zigorra galdegin du Gipuzkoako fiskaltzak. Astelehenean hasi da epaiketa eta gutxienez martxoaren 21era arte luzatuko da.

Matxismoa normalizatzen ari da, eskuin muturreko alderdien nahiz sare sozialetako pertsonaien eskutik, ideia matxistak zabaltzen eta egonkortzen ari baitira gizarte osoan. Egoera larria da, eta are larriagoa izan daiteke, ideia zein jarrera matxistei eta erreakzionarioei ateak... [+]

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

15 urteko emakume bati egin dio eraso Izarra klubean jarduten zuen pilota entrenatzaile batek.

Lestelle-Betharramgo (Biarno) ikastetxe katolikoko indarkeria eta bortxaketa kasuen salaketek beste ikastetxe katoliko batzuen gainean jarri du fokua. Ipar Euskal Herriari dagokionez, Uztaritzeko San Frantses Xabier kolegioan pairaturiko indarkeria kasuak azaleratu dira... [+]

Bi neska komisarian, urduri, hiru urtetik gora luzatu den jazarpen egoera salatzen. Izendatzen. Tipo berbera agertzen zaielako nonahi. Presentzia arraro berbera neskek parte hartzen duten ekitaldi kulturaletako atarietan, bietako baten amaren etxepean, bestea korrika egitera... [+]

Martxoak 8a heltzear da beste urtebetez, eta nahiz eta zenbaitek erabiltzen duten urtean behin beren irudia morez margotzeko soilik, feministek kaleak aldarriz betetzeko baliatzen dute egun seinalatu hau. 2020an, duela bost urte, milaka emakumek elkarrekin oihukatu zuten euren... [+]

Neska adingabeari sexu abusuak era jarraituan egin zizkiola frogatutzat jo du Bizkaiko Lurralde Auzitegiak.

1989tik 2014ra, Frantzia mendebaldeko hainbat ospitaletan egindako erasoengatik epaituko dute. 74 urte ditu Joel Le Scouarnec zirujau ohiak, eta espetxean dago beste lau sexu eraso kasurengatik.