“The Basque Country is the region that is fighting the most against renewable macroprojects”

- Vidas irrenovables (Non-renewable lives) has filmed the consequences of "renewable" macroprojects. The Basque and French subtitles are being prepared) by this independent director, raised in the rural area of Extremadura (Cabeza del buey, Spain, 1985) in the documentary. The film is making its appearance from village to village and with his presence and with 30 performances in the Basque Country from September to March. So far no one has left the room as they entered after watching this documentary...

You have made some basic choices when making the documentary. Independence was first. What is that in practice?

We have been producing Metáfora Visual for twelve years and in the first six years we only advertised for other companies. In 2019 we decided to make our own documentaries and we were clear that we wanted to make them 100% independent, without any public support or collaboration from private producers. For what reason? Because this allows us to be masters of the product, to think freely about what we want to tell, how, when we want to start working...

We save part of the money that the producer earns by advertising to make our documentaries. But of course, doing it independently has a much higher risk, one assumes the total expense, so we have to worry about projecting the film a lot later to get the performance. This forces us to move and helps us to create an audience: as we present the documentary, we create face-to-face relationships with people, we share the day... This way of making films is very enriching. And looking to the future, we know that we have an audience that may be interested in what we're going to do.

Another option has been to give a voice to the citizens who are mobilizing against wind and photovoltaic macro-projects and, instead, not to interview companies and the government. For what reason?

When we started researching the subject, one of the options we proposed was to interview companies and organizations. But as we filmed and met people, we saw that they had been struggling for years, begging to be heard, asking to be taken into account, claiming that there was debate, asking to see what impact they were having on their lives... and they were ignored. That is why we decided that we would not give a single minute to companies or administrations, which have been using all the mass media as their loudspeaker for many years and telling them everything they want. We decided that this documentary would be a window to people who have no voice.

They said it was a partial documentary.

I don’t think it’s partial, because the impression that most of us have – and I thought the same thing until I started researching this – is that there is no other option and that they have to be done at all costs... this thought is widespread and has arisen because of the loophole that the industry and institutions have given us. Since we have this preconception as a basis, we decided to do it this way, so that the whole other side is known and so we have all the cards exposed. Let’s find out how people are affected and then let everyone decide if these projects are good or bad.

Trailer of the documentary. English and French subtitles are being prepared.]

Upcoming performances in the Basque Country

25 FEBRUARY: In San Sebastián at 19:15 in the Trueba cinema.

26 FEBRUARY: In Igor, at 18:00 in the Lasarte room.

27 FEBRUARY: In Balmaseda, at 18:30 in the Teatro Claret.

28 FEBRUARY: Carranza at 19:30 in the cultural center.

28 FEBRUARY: In the evening at 19:00 (no presentation).

1 MARCH: In Urizaharra at 12:00.

13 MARCH: Zarautz at 19:00 in the Model cinema.

14 MARCH: In Araia (without presentation).

14 MARCH: I'm fucking with you.

15 MARCH: In Arano.

Another option was to interview 70 people from 11 territories of the Spanish state. You had 50 hours of recording, and then you shortened it to an hour and a half: There are 47 people on the screen.

We decided to do it this way, because if we had focused on only two cases, there would be a risk that the audience would think that these are specific cases. That's what people think: “They have insisted on our valley, they have sewn us with projects”... and I tell them, “no, no, they have insisted on everything, below the Pyrenees there are no territories with a radius of 50 kilometers that have not insisted, so relax”. But as these citizens are only given a voice in the regional media, people believe that the problem is theirs. The problem is general. That’s why we decided to expand the field so that the audience can feel that the situations from north to south are the same. I think we've done it.

We have filmed in every territory where we have managed to get in contact. There are no projects in the Basque Country because we were filming in 2023 and then there were almost no projects. They appeared in 2024, when we were finishing the recording, and we had so many hours of recorded and advanced storytelling... The same has happened to us in Catalonia and also in the Balearic Islands and Madrid.

I missed Navarre...

Many people have told us, "they have been on the wind for many years"... the Aragonese told us to go to Navarre but we didn't get anyone to talk.

The same thing happened to us in Extremadura, and we are local! Only one local project appears, the only one who speaks is the lawyer, and he is from Huesca. Extremadura is full of projects but nobody wanted to leave.

Why didn't they want to show up?

Because they're from small towns. Maybe they have been positioned for many years and if they also appear on a speaker, it can happen that the conflict is greater, that they point out... there is a big gap in the villages.

Are there any other choices you have made when making the documentary?

We don't do closed scripts. First we are documented by reading the press and scientific articles. Then we talk on the phone with the people and according to what they tell us, we place each one in a series of themes and we develop the script, but without closing too much. Finally, we make a living with the interviewees, we go to them, we spend four or five days or a week with them, we record at intervals throughout the day... Experience has shown us that when we gain confidence with the interviewees they tell much more interesting things, so as we meet people we change the script, we work in a very free way.

With so many hours of recorded interviews, to decide which topics to include and which to exclude in the documentary, we were clear that the most important thing was how it was narrated, because that is what generates emotion and empathy in the audience. And that's the only thing that can make a change.

On the other hand, we have not used narrators or off voices: the thread is sewn through dialogues that link the protagonist to the protagonist. They must be selected so that the sequences are linked to each other so that the thread reaches the viewer. We have omitted some very good passages because the thread was lost.

It seems to me that the landscape is the main protagonist of the documentary: wealth and extermination, both appear. What is the landscape for you, who grew up in a small village in the countryside and made this documentary?

“Of course these macro-projects affect us all because they are high-volume infrastructures that will condition the environment for decades to come.”

As the geologist José Simón says in the documentary, the landscape is all that surrounds the environment: natural heritage, cultural heritage, people, animals, plants... we are all part of the landscape. The drastic change that these projects cause in the landscape affects us all. It affects wild animals: they decide to leave, they don’t stay around the aeolians if they have the freedom to leave. It affects domestic animals because it changes the way they are managed. And although many say no, it also affects people: it affects you psychologically, in your relationship with your environment. For example, the documentary features two Burgos brothers who are pastors and whose father, who is over 90 years old, has stopped looking at these mountains for 25 years, since the wind turbines were made. Of course it affects us all, because they are high-volume infrastructures that will condition the environment for decades to come.

The film puts on the table a topic that is usually hidden: the conflicts that these projects generate in the villages, by means of money. The Matarranya Valley in Teruel is shown as a positive example: in it the citizens faced the companies...

The citizens of Matarranya saw how the inhabitants of Terra Alta in their area had been living with wind turbines for more than 20 years; and they saw that the villages had been emptied. They also saw that the same thing happened to other areas of Teruel. And the citizens of Matarranya knew that sooner or later the companies would also reach them. So they confronted them and began to inform people. So by the time the projects arrived, the village was already aware. Some municipalities in the valley were initially in favor of these projects, but the population pressured the municipalities to carry out popular consultations, and they managed to get the municipalities to support them as well. That's how they avoided the conflict in the country.

What causes conflict in cities?

“The lack of transparency on the part of companies and administrations generates conflicts in the localities”

Lack of transparency. There is a high degree of opacity on the part of both companies and administrations. Companies go from landowners to landowners, instead of bringing them all together. In the few cases where they meet everyone, the company tells what it wants: it will pay so much per hectare, it will bring great profits, it will create many jobs, it will bring a lot of money to the people... Each one makes a movie in his mind and some landlords say yes, others say no, the others stay if I have... Let’s say that if a landowner with 20 hectares has been promised 1,500 euros per hectare, it is 30,000 euros per year, and he has signed it immediately and he is desirous; and then he knows that his neighbor has said no and that he is postponing the project for him. This is where conflicts begin.

If the municipalities were to exercise transparency and put all the information on the table, this would not be the case. It would be discussed respectfully and calmly, not with the urgency of who has the project on them. On several occasions, in the case of public mountains, citizens have learned about the project when the Town Halls had already done everything. In these cases there is a great conflict, those who support the municipality will defend the decision, those who disagree with the politicians who are governing will oppose it... a serious climate of conflict is created, and once the coexistence is broken it is very difficult to recover it.

It is necessary to inform and not impose, that everyone makes his or her own decision, but saying things as they are: they will pay the landowner more than 1,000 euros but this must be taxed; on the other hand, the landowner will have an additional income and this is also taken into account when making the income statement; this land will go from rural to industrial use and this has a different Real Estate Tax; the clause that they put in many contracts is that if the price of electricity falls, the rent of the land also falls.

The ecological group GEPEC in Catalonia tells the landowners: “I’m not going to tell you if you have to sign or not. What I recommend is that you go to a lawyer and don’t sign anything first before the lawyer reads the contract.” In almost 100% of cases, lawyers advise not to sign the contract because it is not clear who will dismantle the infrastructures once they stop using them, who is responsible for these wastes...

All this is not counted by the companies and the administrations that support it.

Another case that appears in the documentary is that if the landlord does not collect the rent, he does not even know who to claim...

The problem is that these companies are usually instrumental, created with minimal social capital, only to obtain permits and processing, and once the wind or photovoltaic polygons are created, they sell or transfer them to both industries and investment funds. In short, they are the same, because the owners of large electrical industries and those of investment funds are the same.

In the making of the documentary we have met the landowners who have stopped receiving the rent. We have also met the municipalities, which have stopped receiving the rent of public mountains. And they don't know who to claim that money from. They have explained the problem to the administration and the response they have received has been “that is a contract that you signed and you are responsible”. And many times, people who don’t get paid say they’ve been bullied because they don’t recognize that they’ve been tricked, or because they’ve defended the project passionately from the beginning.

It doesn’t always have to be that way, they are charging rent in other places and they are satisfied, although what was originally 1,000 euros in reality was 700. Companies play a big role with the fact that many of those who have inherited the land today don’t even know where it is. If these people were paid by the farmer 100 to 200 euros and now they are offered 1,000 euros, they accept it directly and then what they charge is 500 euros, they deserve it, they have no connection with that land, they have never cultivated that land...

The subject of revolving doors appears in the documentary. The mask of democracy falls on these issues...

Absolutely, absolutely, absolutely. That's the most hypocritical. Companies are often taken into the spotlight and it’s fine, they should also have an ethical code, but well, companies are always the company. On the other hand, it must be the government that must ensure that these absurdities do not occur and prevent such impunity, and that is not the case. Those who hurt me are the public administrations, politicians and officials, because they are owed to us, they are paid for by us in these positions. When a democracy is so corrupt, call it democracy, but for me it is no longer so because people are not cared for.

These projects are declared to be of “general interest” in order to be carried out...

They have a 100% private interest. If you want to install solar panels in your house, they will bother you a lot; whether you want to make a window to the house or change four tiles... and these companies will transform the landscape, transform the lives of all the locals and have the free way to do anything. There are drones that measure the size of the mobile, and in some areas they can not be used to avoid damage to the birds, very well, but right there they can install 50 wind turbines with 100 meters of arms, being bird crushers!

What does the documentary do to people who watch it?

There are two types of audiences. On the one hand there are those who have been struggling for some time, those who have been informed, those who know what these projects can bring... but still, the documentary makes an impact because they realize their size. The wind makes an impact on the one who fights the photovoltaic and vice versa, the one who fights the wind thinks the photovoltaic is more benign, but when he sees this vast sea of mirrors, he thinks: “I don’t know what’s worse!” In these people, the documentary also generates the desire to continue fighting, because they see that they are not alone, that many people are fighting in the same battle.

The impact that other types of audiences, i.e. those who are not struggling, feel when watching the documentary is even more enormous. A lot of people come out of the movies crying. More than one has told us that he has suffered back pain because of the tension... most of them do not know this part of the projects, everything is considered wonderful, and when they see the extent of the massacre and that it will affect all of us who live in the city and in the countryside, they are very affected. Many come out of impotence and others show their willingness to help, for example, after watching the documentary, biologists and engineers have come to ask us for contact, ready to put their time and knowledge at the service of platforms.

Four of the projects featured in the documentary have been stopped since then.

Yes, and many other projects that have not appeared in the documentary. First, because people are fighting. Secondly, in this great wave, they themselves know that despite the presentation of fifteen projects, there are three that will be carried out. The projects stop if he fights. But we can stop one project in a valley and have two more new projects on top in fifteen days. The struggle involves a lot of work and fatigue and for that reason, the more people, the better.

You’ve been in the U.S. a lot of times documenting. How do you see it?

“Neither the administration nor the companies are interested in noise because the message falls; they prefer to go somewhere else”

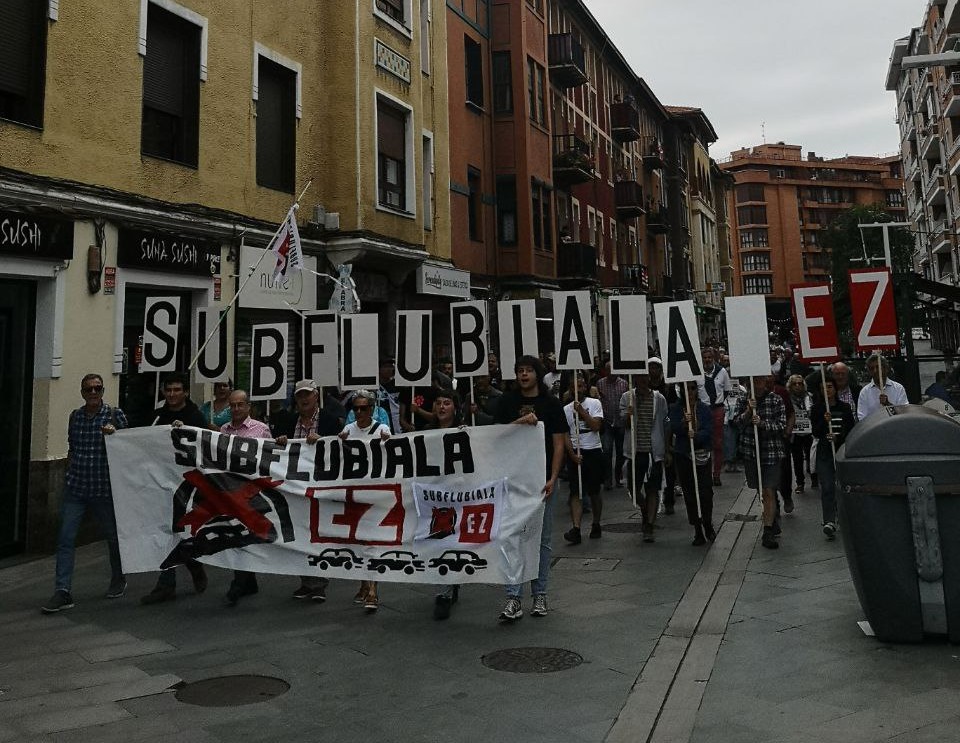

It is the territory that is struggling the most for the short time it takes: the one with the most platforms –there is a team in almost every village–, the one with the greatest and most organized struggle... It is one of the territories where the documentary is most projected. There is movement and with the sound that people are making, I think a lot of projects will stop. Because one thing we have seen is that where the noise is made, it stops, not because the administration and not the companies are not interested in the noise, because the message falls; they prefer to go somewhere else. It's going to be a tough fight, but it's a territory with experience in fighting.

Lehengai anitzekin papera egitea dute urteroko erronka Tolosako Lanbide Heziketako Paper Eskolako ikasleek: platano azalekin, orburuekin, lastoarekin, iratzearekin nahiz bakero zaharrekin egin dituzte probak azken urteotan. Aurtengoan, pilota eskoletan kiloka pilatzen den... [+]

Today’s Venice is built on an archipelago of 118 islands. These islands are connected by 455 bridges. The city is based on mud rather than Lura. Millions of trees in the area were cut down from the 9th century onwards to build piles and cement the city. Years have passed and... [+]