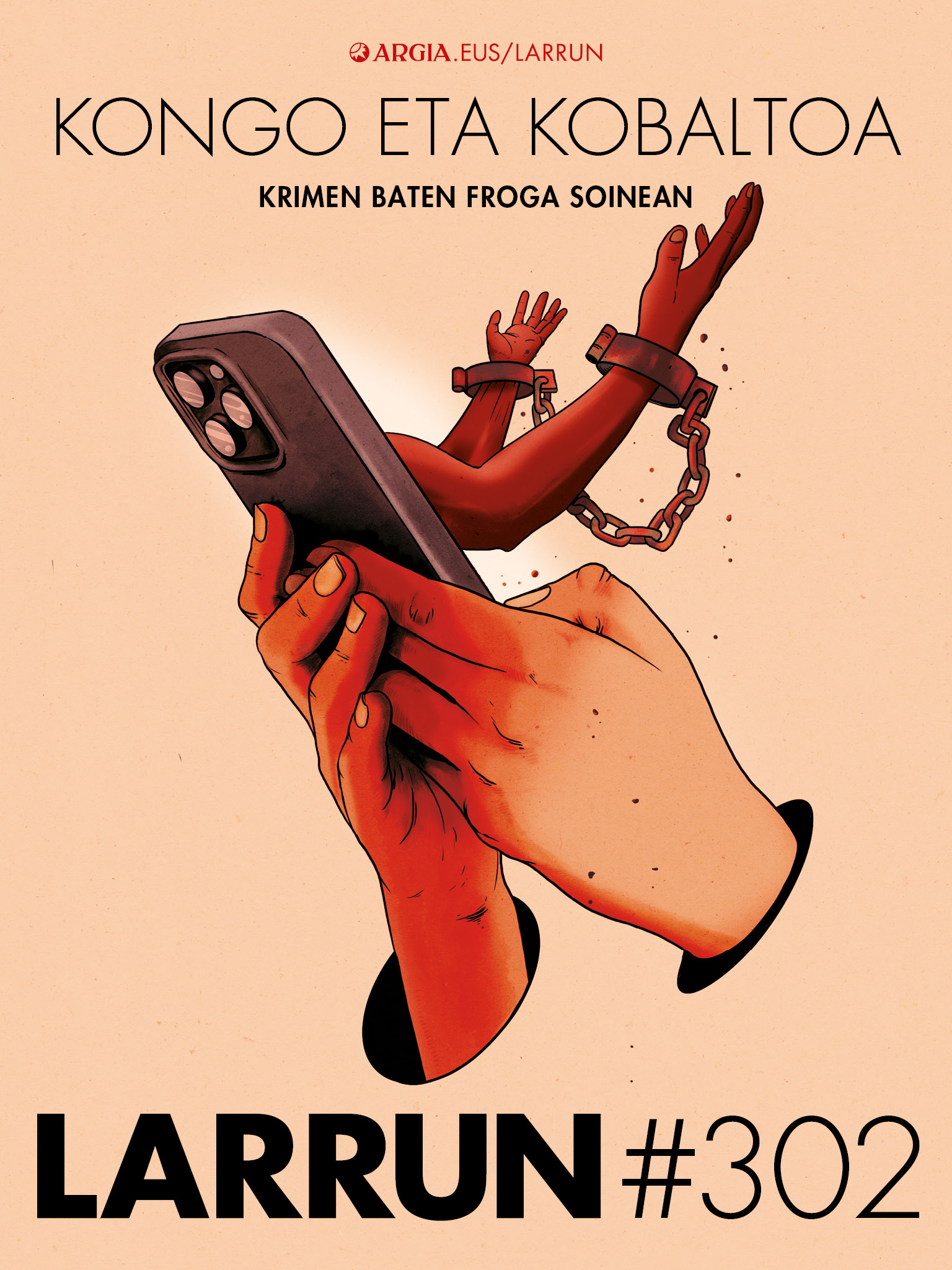

What are we willing to stay connected for?

- It serves us to take this last portrait with twilight. Or the little puppet that we just asked the waiter of the pay bar in a moment. And, wow, in the back pocket of the pants that want to mimic the Levi’s come perfectly. The cell phone also serves that. So who cares that in the background, we're a little bit of proof of a crime? It's just a few grams. A little chute. Seriously, what damage does it do? In 2023, for the fourth consecutive year, production was exceeded and 230,000 tons of cobalt were extracted in the world. 2024 will not be different. This mineral is essential to increase the duration of lithium ion batteries, we move through it. In fact, in addition to turning on Android and iPhone screens, it's a basic raw material for renewables or electric cars that say they're going to take us to the energy transition; for each battery, it takes 13 kilos of cobalt. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, half of the world ' s cobalt reserves are concentrated, of which 76 per cent is now being extracted. But we return child exploitation, accidents and pollution to the Congolese. Unfortunately, it is not new, because the same has already happened with the ivory and rubber industries: they were given slavery and genocide in change. We've hung on a map that dreamed place that's called progress, without realizing that we've reached the past of pounds and grams, in the heart of 19th-century Africa.

Ferdinand Lassalle runs a alley between Lumumba and Shuman streets. He stretched his neck and frowned when he closed his eyes a little bit, as if he wanted to focus a little more. One of the hundreds of demonstrators who have gone past the Place du Luxembourg has drawn attention to the affixa in his hand: On nous tue à cause de nos richesses (They kill us for our riches). Others bring blue and colorful flags, and Stop Genocide! Stop the War! The megaphone moves in its mouth screaming its slogans, while the gabardines and the necklaces were tightly attached. It's cold in Brussels. 25 February 2024.

Lassalle has taken the notebook and pen out of the inner pocket. He is a classic, elegant journalist, who knows how to squeeze small details. He overlooked the humility of the stickers glued here and there on street furniture: Let’s start talking about Congo, they say quietly. The march has been organised by the Congolese diaspora of the European capital to denounce the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). March decided in 2022 to return to the offensive in the Rutshuru Mountains in North Kivu. The population lives in a war context that has never ceased and, although it varies according to sources and years, it can be said that the war has already caused between eight and ten million deaths since 1990.

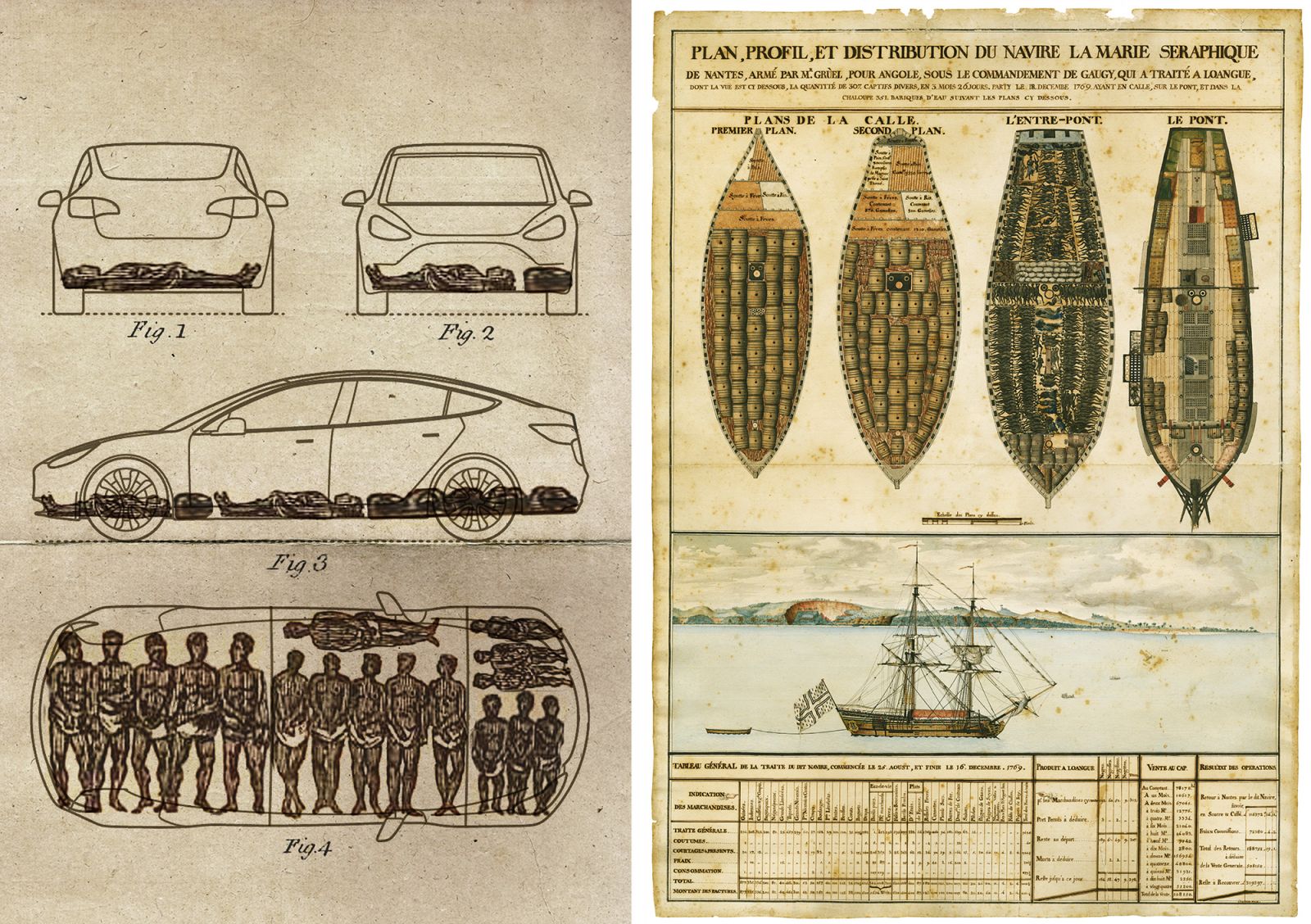

But when protesters talk about genocide, they also talk about an invisible crime that has been repeated continually over the past five hundred years: starting with slave trade, continuing with the horrors that have been made to get rich with the Belgian rubber Leopoldo II.ak – still millions dead – and also with the perpetual situation that today continues with the misery of mineral exploitation.

The private mining company Albanian Minerals of the United States estimates that the value of the mining resources in the subsoil of the KED can reach $35 trillion. Labour and natural wealth, that is the double condemnation of the Congolese. That's why they're killed. The same is true in the east of the gigantic country, in the vicinity of the Great Lakes of Africa, to find gold and diamonds and sell them in the luxury jewelers of Paris and New York, as well as in the mines of Katanga or Lualaba of the south to extract the cobalt and power the lithium ion batteries that the world needs to stay connected with it. Cobalt is one of the biggest slaves of the 21st century.

“With proof of a crime,” Lasalle has two or three times highlighted the words, thoughtfully, trying to explain the idea that has revolved around him. This time it seems to have been right. It serves the phrase. The journalist has re-entered his pocket and quickly returned to the past, 120 years ago, to his hut or paillot in Yangambi, the embodiment of the fictional character created by Bernardo Atxaga for his novel Zazpi etxe France-Spain, set in the Congo, dependent on Belgium. He will be the guide to this journey that has no timelines.

*****************************

Because this journey has not a single port of departure, nor a specific moment. The history of Congo is as long as it is inaccessible to make the four cardinal points of a map fit. Perhaps if we were to give a symbolic start to the crime suffered by the Congo, we would mention 1482. Just as the indigenous peoples of America have a fatal year, so do the Africans, a decade earlier.

In that year, sailor military captain Diogo Cão arrived by boat at the bay of Loango, south of Ecuador, on the longest journey a European had made until then. King John II of Portugal was in charge of starting the expedition in Lisbon a few months earlier. The goal? Gold. After passing through Cabo de Catarata, he found the mouth of a river of great flow. The local bantús knew their intimate secrets very well, and they called it Nzege, the river that devours all the rivers.

A stone

The Portuguese conqueror put on the ground a padrão, a stone, to tell everyone that from there all land had a unique owner. Then he made a second trip and continued to climb the waterfalls of the river. Another godfather. And he sought the gold he wanted in business with the authorities in the kingdom of Congo. Legend has it that Cão died on the hunt for a crocodile. But this was already the case, because the blissful stones on the shores of the Congo would from then on mark the fate of millions of people. The Loango Bay became the station of many European expeditions in the following centuries, and not only that, but also the beginning of a tremendous slave trade.

In the 15th century, shipbuilding began to evolve like a hungry marine snake for long journeys across the ocean. After placing the Latin candles to the carabela, the Portuguese managed to make the pot large enough to store in their stomach a large amount of food for many days. The Basques were also not left behind in this race, as even larger and heavier boats emerged from the docks of the Cantabrian Sea for the great catches of the kingdom of Spain in America. And the conquerors, too. And with the Portuguese as intermediaries, the traffickers participated in slavery and the feeding monsters...

In the bay of Loango, in the village of Diosso, there is a great stone. It's not the one Diogo Cão put in. In 2008, it was included in the World Heritage List by UNESCO, as it is one of the main ports of slave transport from the 16th to the 19th century. They set up a monolith to celebrate it. Departure of caravans. The town of Loango, the first place to ship about 2 million slaves, says a simple dark slab at the foot. Ferdinand Lassalle pointed the pencil in the drawer: “2 million blacks.” How much is that? How many rods can cut four million hands? And have some captures been drawn or has a cobalt been extracted? He wondered.

In the bay of Loango, in the village of Diosso, there is a great stone. It's not the one Diogo Cão put in. In 2008, it was included in the World Heritage List by UNESCO, as it is one of the main ports of slave transport from the 16th to the 19th century. They set up a monolith to celebrate it. Departure of caravans. The town of Loango, the first place to ship about 2 million slaves, says a simple dark slab at the foot. Ferdinand Lassalle pointed the pencil in the drawer: “2 million blacks.” How much is that? How many rods can cut four million hands? And have some captures been drawn or has a cobalt been extracted? He wondered.

Pool Malebo

More than 12.5 million people were kidnapped and transferred from Africa to America in four centuries, of which nearly 6 million were landed on the shores of Loango and Angola, according to the Slave Voyages database. The first boat sailed from the shore of the Congo in 1514, with a Portuguese flag, 237 slaves, and when it arrived in Vigo, only 168 remained alive.

But with homogeneous terms of “slave” or “African” we cannot fall into simplifications. Many kingdoms and people of peoples were enslaved. In the first phase, for example, the Pool Malebo area was the largest slave market. In this natural lake created by the Congo River, there are currently Kinshasha and Brazzabille, capitals of the KED and the Republic of the Congo, but at that time it was controlled by the people of Teké. More to the north, on the other hand, there were bobangias, landowners of land that survived the course of the Ubangi River and that had been introduced into slavery to the knees. Subsequently, the traffic spread to the kingdom of Loango and at a later stage also deviated through the Niari Valley as a tsunami.

All these details are due to the Congolese historian Arséne Francoeur Nganga, who has closely investigated this territory. According to him, the banks of the right bank of Pool Malebo were fundamental to supply slaves to the insatiable market, and the epicenter of Brazzabill was the building now housed by the City Hall. The people who had been imprisoned in various places piled them up and from there took them directly to the shore of the sea, to put them in the hands of the Europeans: “It was the largest slave market in Central Africa, but unfortunately there are no plates or events here that remember it,” says the researcher Ziana.Tv on the television channel of the Congolese diaspora.

In Loango, beyond that cold monolith that begins to lift up the painting, Lassalle has barely seen anything. He has found a small museum in Diosso, where he shows his customs and art. And it's facing a big tree. Then the museum watchman came to him. His name is Joseph Kimfoko, and he has been complaining about the government for years about the bad situation in the museum. According to the journalist, they used to force slaves to go around the tree seven times to forget the past before embarking on a "no return" journey. Reset the memory so submission prevails. There are more trees of this kind on the west coast of Africa.

The Portuguese never went too far into the Congo, they preferred to marry the daughters of local leaders, and became a tangomão that dominated their culture and language to mediate human flesh. Perhaps in this way we will better understand how the demons kept that cavity for more than three centuries so far away from the claws of the European expoliadores. However, in 1851, a Scottish physician named David Livingstone, with a quinine pot in his pocket, discovered that it was effective in dealing with malaria, crossed the Zambezi River of steam into the stream. And he thought, “Will there be something similar that leads to the heart of Africa?”

Lassalle runs through the leaves and branches of the gigantic mangoes. Following the naked footprints of the slaves, he enters the path that goes to the coast of Loango. The mango is very special for the descendants of the slaves. The Portuguese brought the fruit tree to Africa in the sixteenth century, domesticated, and it is believed that the mangoes of over 300 years now seen in Loango are the pups of the seeds devoured by those poor devils who with their feet headed towards the boat.

That's what the legend says, but now it's the same. They took them. Two million. All in the belly of the snake. Once on the cliff, the journalist has looked at the large Atlantic. He heard not the rhythmic noise of the waves, but the scream of a mandrel, similar to the chillids that were heard on the beach, on the shore of the Yangambi River, while they were cognating.

Copper Belt

Linvingstone spent twelve years exploring the Great Lakes of Africa in order to find the Nile spring. In 1872 he arrived at the Lualaba River. It's over. Arab slave traffickers did not allow him to go less than a meter. Desperate and sick, he returned to Tanzania, and soon met Henry Morton Stanley. A missionary doctor and a racist correspondent. Two white men commenting on the fate of an entire territory... I'm imprisoned. Clac! At that particular moment, the old Kodak Lassalle camera has buried the historical event.

Lualaba is currently the southern province of KED and is located west of the Copper Belt. It is a giant, rich, horseshoe pit of hundreds of kilometers, unrivalled in the world. In addition to the sea bass, it occupies large areas of Alta Catanga and Zambia. Copper, nickel and cobalt are the most abundant metals, but there are others, such as uranium with a concentration of 75%. During the Second World War, the Americans got the material to make an atomic bomb from the Shinkolobwe mine in Katanga, which was then in the hands of the Belgian company Union Minière, and that secret plan does not know how many people died from causes related to the forced extraction of uranium.

Why is this area so special? Apparently, due to a whim of tectonics, copper and cobalt minerals are located at a shallow depth of the Earth’s surface. Below the water table, the cobalt appears together with the mineral carrollita, and from there, in a heterogeneous form by oxidation: “Katanga cobalt pits are unique. They are blocks of several kilometers and the grapes float like a bollo,” explains the geologist Murray Hitzman to the writer Siddhart Kara in the book Cobalt Red (Kobalto Rojo).

Wheeled mines

Western countries have based the energy transition on the exploitation of critical raw materials such as cobalt. According to a report by the International Energy Agency, between 2017 and 2022 global demand for cobalt rose by 70% and that of nickel by 40%. Behind this growth is the renewables sector, as wind turbines and solar panels need a lot of metals and rare earths for their operation (lithium, cobalt, neodymium, copper, silver, gallium, graphite...). And the same is true of electric cars; experts say that as mobility is electrified, demand will increase enormously, but it's not enough for everyone.

Revista Elhuyar (nº 353) A report published by Egoitz Etxebeste describes electric cars as “wheeled mines”. “The electric car is a great class elephant,” explains Alicia Valero, researcher at the University of Zaragoza in the same report. Such a vehicle can carry up to 13 kilos of cobalt, more than 40 kilos of nickel and 9 kilos of lithium. In view of the degree of depletion of these materials, Valero believes that “throughout the world the energy transition that has been proposed in the global north will not be possible”.

So, on the one hand, we have a lot and at hand in the Democratic Republic of Congo -- almost 60 percent of the Earth's reserves -- a high-law cobalt, very scarce in other places, and on the other hand, this metal has become something essential in the energy model designed for global interconnection ... It is no wonder that the African country is one of the black spots in the world of economic interests and exploitation.

Congogate

Siddhart Kara has known firsthand the mining situations in the Congo. The American writer, professor and activist, of Indian origin, has experience in the study of slavery in the twenty-first century. He has crossed half the world trying to document cases related to sex trafficking or child exploitation, and he has written numerous papers about them on media such as CNN, The Guardian or the BBC.

Cobalto Rojo has been published by the editorial Captain Swing in the book Cobalto Rojo. Congo bleeds to connect you (Red Cobalt. Congo bleeds for you to connect – it perfectly describes the conditions under which the Congolese take the cobalt by hand. But not only that: it's also tested the connection between suppliers. The multinationals say that their supply chain is “transparent”, but Kara sees with her own eyes how they take advantage of the work of children and the enslaved craftsmen.

This chain includes well-known technology companies (Apple, Microsoft, Google...), battery manufacturers (CATL, Samsung, Panasonic...), large mining companies and Chinese intermediaries – since the signing of the “dependent contract” with Beijing. From the outflow of the subsoil to the London Metal Exchange, the author has demonstrated the bribery that exists on the long road that runs through the cobalt, and has put figures on the theft of resources to the Congolese: billions of dollars. How much is that for a poor country with a budget of just 6.9 billion dollars? More than one has called for the Congogate scandal, and not for a minor reason.

The horror

This fact has not impressed Ferdinand Lassalle too much, who has lowered the flap to the cap. He knows how far corruption and cruelty can go when the greed of the white man is interposed. I had seen it in Yangambi, the life of a black man was not worth a rifle bullet ... The registration began to swiftly backward until he found among his pages a cut from the newspaper Le Peuple, dated June 11, 1904: “An immense cuve dans laquelle fermentent les atrocités, les oppressions et les cruautés”. Barbarism, oppression and cruelty are constantly becoming aggravated, as the Belgian leftist journalist describes what is happening in the particular winery in Congo, Leopoldo II.aren.

A report by the British Consul in the Democratic State of the Congo, Robert Casement, was discussed in the UK House of Commons that year. The Report was an incentive for the Belgian monarch to dissolve from his possessions in the Congolese territories. However, the international campaign against inequalities in this country had begun earlier.

Edmun Dene Morel, an employee of a shipping company in Liverpool, discovered in the 1890s that there were millions of francs of gap in ivory and rubber that was imported from the Congo Free State to the port of Antwerp. He also collected testimonies from missionaries about the treatment of Congolese people in the Leopoldo colony II.aren. Someone was getting rich at the expense of that exploitation. In the same years, a sailor with a vocation as a writer climbed through the river, in the heart of darkness.

"The horror! The horror!” This is the only thing Joseph Conrad, one of the protagonists of the famous novel Heart of Darkness (Ilunbeen bihotzean, 1899), sick, hallucinated, in moments of premature death. What did you see and what did you do in those ivory explosions in the Belgian Congo? “In this book there is no beginning or end in itself, because the end is to return to the beginning, to the beginning of civilization and to the night of London,” says Iñaki Ibáñez in the introduction to the Basque translation of Ilunbeen bihotzean (Ibaizabal, 1990). Let us therefore go back to the time when the Congolese forests were left to the Belgians.

One hand

In 1876 he founded the Leopoldo Association II.ak Association Internationale Africaine (AIA), with the objective of developing a plan that had been in the head for many years. He researched the system of Spanish slave colonies in America in the Archivo de las Indias in Seville – at least that says historian Adam Hochschild in his bestseller book King Leopold's Ghost (the ghost of King Leopoldo) – and wanted to copy something similar for Africa. By then the powers of the world had already taken over the continent: France West, United Kingdom East, Germany South... Only the territory of the center remained “free”.

And the monarch didn't waste the time. To take advantage of this territory, he hired the services of the young Henry Morton Stanley, who had just sailed all over the Congo. It would be a civilizing mission. Stanley had fooled dozens of Congolese chiefs to steal the lands and, to whom he was unwilling, punished him with a scourge of hippopotamous chicotte. Boom! Or simply “shoot like a monkey,” according to contemporary English explorer Richard Francis Burton. Interestingly, in the Basque Country, in Vitoria-Gasteiz, a street still bears the name of this civilized character, as Stanley visited the city.

He managed to arrive in time at the Berlin Conference of 1885, where Leopoldo II.ak was distributed with Cartabón Africa. Congo remained in its hands. Literally. From then on, the Democratic State of the Congo became its personal property. A private land is 76 times larger than that of Belgium.

To weigh up the territory as much as possible, the Belgian officials opened up terror. For example, each family was asked for a quantity of rubber, and if he came back from the jungle without that material, his hand was cut off from one of his relatives. Hand, nose, head -- mutilations were a daily punishment. And the chicotte. Boom! Boom! According to Hoschschild, the population of 20 million people in the Congo was halved in a short time.

Antwerp coffers, on the other hand, were plundered by exporting rubber, as in European cities the demand for wheels and bicycles increased enormously. But in the early 20th century, the rubber market started to run out, and prices went down. This probably had more weight – than any campaign of international pressure – in the decision to deliver the African colony to Belgium in 1908, Leopoldo II.ak. Yes, he received a “compensation” of 50 million francs for his generosity.

Limited narrative

The Belgians did not have to squeeze their heads too tightly to know how to take advantage of their king's gift: the copper was the new rubber, the slaves the old instrument. They tinted. The catangaros had known for a long time how to extract the copper from the ore, and the colonizers soon looked at it. In 1906 they founded the company Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK), and soon huge mines were opened around the city of Élisabethville. As the catangaros did not have enough hands, thousands of slaves transported from other places were exploited. Art.

After the independence of 1960 in the Congo, the short window of hope opened by Patrice Lumumba was suddenly closed down by the secret services of the United States and Belgium (see table) and Mobutu Sese Seko sent for 30 years on the renamed giant Zaire, an unfortunate transcript of the word Nzege of the Kikongos. Corruption, pillage and inequality were imposed. Subsequently, starting in 1997, it became the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the country was in the hands of Laurent Desiré and Joseph Kabila, father and son, plundered again by violence to their advantage.

The aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, the “Second War of the Congo” launched in 1997 and the intervention of other countries in the West and Africa, has caused millions of deaths and dozens of cruelties in another three decades. Hands, noses, heads -- again. According to data from the International Organization for Migration in Geneva (IOM), in 2023 there were seven million people displaced inside the DRC by conflict.

The current president, Félix Tshisekedi, wants to revise the Constitution on the pretext of making war in the eastern provinces such as Kivu with the M23 group and other rebels. For many, however, Tshiseked is looking for a third term: “Several researchers, anticipating the repression of the protests, are emphasizing the need to document everything,” said journalist Oskar Epelde in one of those imposing sound chronicles he is carrying out from Africa for the Basque Country Irratia.

It is true that the history of Congo is inaccessible, but we cannot think that the only cause of the crisis it is suffering is its minerals and international interests. “A limited narrative can oversimplify the dynamics of the conflict in the Congo and underestimate the importance of local factors,” says Tricontinental researcher François Polet Centre. Congo (DRC). Reproduction des prédations Reproduction of catches) has published a special journal with articles by several experts from the Congo area, under the coordination of Polet. With a compassionate look, we will only be able to draw a Congo that does not exist and that “can be” on this map, rather than counting the country that it really is.

Portrait of pollution

Élisabethville. It is the old colonial name of Lumunbashi. 2,200 kilometres from Kinshasa. The capital of Katanga and the second most populous city of KED. Two million inhabitants. At dawn, the sun woke up again from a leap and in a minute illuminated every corner of the city. “Kapuscinski is right,” says a voice quietly, while the rays spread millions of particles of flying dust.

The Polish writer wrote in the masterpiece Heban that light overflows on this continent: everything is lightning, everything looks, everything is very bright. Klak-klak. Ferdinand Lasall has kept the coding in the bag and shaken the dirt street with some leather boots, without losing some elegance. When dust has been postponed, however, it has happened with a fortuitous landscape.

In the mining territories of the Congo, in both Katanga and Lualaba, “the buildings, houses, roads, people and animals are covered with craca,” explains Siddhart Karak in the book Kobalto Gorria. Same in Lumumbashi as in Kipushi or Likasi. In Likasi, for example, “air pollution has reached dangerous levels. A cloud of smoke, dust and ash is blinded throughout the region,” says Kara. There are no flowers, no streams, no birds. Nature has disappeared. It looks like a simple ocre watercolor, a perfect portrait of the environmental catastrophe caused by mining in the 21st century. Clac.

Slaves

Our guide has reached a mine called Êtoile, not far from the center of Lumumbashi. It is the first that the Belgians opened up in Congo in 1911. When Mobutu nationalized the company UMHK in 1967 and instead founded Générale des Carrières et des Mines (Gécamines), he was left in his hands. The dictator used the state company for decades for personal enrichment, until the financial crisis occurred in 1990. Since then, the Congolese Government has continuously sold mining rights to foreign multinationals, and today most of them are Chinese giant companies that form a “mixed” model with a small share of Gécamines.

Diesel or slave labor. In a mine there are no more motor forces, as the geologist Antonio Aretxabala says. In 1997, Êtoile was also the first to implement artisanal mining: the workers, by hand, extract the cobalt themselves, most of the time clandestine in mining areas, then sell to the négociants or intermediaries for four salaries, and at the turn, the materials end up in the trucks of the multinationals. According to Kara, 30% of the cobalt exported from the Congo is produced in this way. On the other hand, it should be taken into account that the artisanal heterogenite has ten or fifteen times more “law” or quality than the industrial heterogenite.

This opaque system allows companies to dock, but who pays? In underground wells there are accidents, there is child exploitation, there are penalties... In Tilwezembe, for example, in the province of Lualaba, a mine 30 kilometers from the capital, Kolwezi, Kara saw two thousand or three thousand children “at any time” working for a dollar a day. If they did not obey their bosses, yesterday! Some of them remained closed in dark transport containers “without food or water for two days”.

Slavery continues in the Congo. Debt is the best chicotte: children are forced to dig a hole in the ground until they find the mineral, paying misery every day, and then, on the pretext of paying the money, they are held prisoner by pulling out the precious heterogeneous with their bare hands. “Can a company located at the top of the supply chain really say that the cobalt of its appliances or cars has not come out of a market like this?” the writer said in the air.

Macano

Not far from Tilwezembe is the largest cobalt mine in the KED, located between the cities of Tenke and Fungurume. The name is also not original: Tenke-Fungurume Minning or TFM for everyone. 1,500 square kilometers. Like the metropolis of Greater London. Bigger than Lapurdi. In 2016, multinational Freeport sold its share of the mine to the company China Molybdeum Company (CMOC), thus becoming the world’s largest cobalt producer, ahead of the other Swiss giant in the sector, Glencore.

Lassalle heads to the southwest of the city of Fungurume, to an infinite neighborhood. He bent his head to enter the door of the brickwork hut and as soon as he entered, he had to take the silk scarf that he carried to his neck. A pestilent smell invades the entire environment. On the ground, sitting and without strength, he's seen a boy. Thin limbs stand out from a broken table. What is it? Where had I seen the scene before?

His name is Makano. He is only 16 years old and in the book Kobalto Gorria we can read his testimony: “The father passed away three years ago,” she explains. I am an older son and now I was responsible for making money for my family. I started hanging out with some friends in the campas of southern Fungurume. We punched small wells, sometimes we found the mineral, sometimes we didn't. We didn’t win much and we thought it was better to start going to the concession.”

The concession is a giant operation of the CMOC within the TFM. Every night they were silent, and after many hours of work, because Macano had no bicycle, he was carrying on foot a heterogeneous 40 kilograms of weight. Good quality cobalt, but in spite of everything, the bag was worth only two dollars.

On May 5, 2018, after spending the whole night punching, the young man rushed and suffered an accident as he left the well with his bag on his back. He remembered that he was in a hospital in Kolwezi: “He had his legs and hips torn apart, his wounds everywhere and his head swollen,” he says. The family spent all the money it had for a life-and-death operation, and the doctors put a long metal rod on his right leg, which was sent home a week later. Macano is deeply wounded and has a fever. He needs antibiotics so he doesn't get into shock. “I know my son is dying. She has to go to the hospital, but I don’t have money,” explains Mother Rosine, who is nearby.

At the Shabara Mine

Since his first trip to Congo six years ago, Siddhart Kara has often experienced harsh situations. In Fungurum, thousands of citizens have been driven out of their homes to set up a mine, left without anything, and all they can do is exploit the mineral themselves, even if it is illegal. But when the multinational company prevents them from accessing the mine, the tension collapses. As in June 2019: Soldiers were sent and several people shot to death. As with the rifles of yesterday's colonizers, today's pods emerge from the Kalaxnikov.

Artisanal miners often create cooperatives that supposedly improve their conditions. In the province of Lualaba there are two main: Coopérative Minière Maadini kwa Kilimo (CMKK) and Coopérative Minière Kupanga (COMIKU). In theory, they control the activity through registration cards and there is a “Mining Code”, but in practice bribery and labor exploitation are also present. Right in the mine of one of those cooperatives, Shabara, Kara saw an image that Kara will never forget: “15,000 men and adolescents shouted with hammer and paddle inside a crater, with little space to move, not even to breathe.” Klak-klak-klak-klak. The photo has turned around the world and appeared in the world's leading news agencies.

Elodie

Chaos is apparent, as in this disorder there are always levels and hierarchies. They are often organized in family or in groups, and each one has its role. Men extract heterogeny in dangerous tunnels that are deadly traps, young people transport sacks, children crush material and children clean them in rotting water wells contaminated by metal spills. In that link, the last and the biggest losers are always women, even more so if you're an orphan.

Elodie was 15 years old when he met Kara. I was hitting the ground with a steel bar near Lake Malo looking for cobalt. $0.55 per day. It was barely “bone and tendon” and with each cough it seemed to break his ribs. AIDS was in an advanced situation, including the author.

His father, buried forever a few years ago by a mine from the multinational Glencore, died of an infection by the cleaning of the cobalt in dirty waters. Elodie had a baby on her back, held up by a rag made of jirons. Your baby. He's read well, Elodie was 15 years old. And in order to survive, I was forced to prostitute myself among soldiers. Muango yangu njoo soko, he said, my body is my merchandise: “For him, prostitution and the need to dig for cobalt were the same,” Kara added.

*****************************

Amnesty International has denounced that in the Democratic Republic of the Congo at least 40,000 children are working in the mines, which only have breakfast in the sun. The same organization researched for the first time the trajectory of cobalt in another dossier published in 2016: after being processed it remains in the hands of China and South Korea companies that manufacture battery components, sell components to battery manufacturers and end up in products from technology and automotive companies. Apple, Volkswagen, Tesla, Sony, Dell, Vodafone, Lenovo, Renault, Huawei… There were 29 multinationals involved and, according to Amnesty International, the vast majority have done nothing to change the situation.

Let's start talking about Congo. Let’s start. And let's start talking about why the Global South has to suffer the burden of the well-being of the West once again, the burden of the devices that we carry in our pockets or on the wheel.

According to the latest EiTB Date survey, the sale of "low-polluting" electric cars in Álava, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa has risen from 10% to 60%, respectively. There and here wind and photovoltaic power plants will be built; in Navarra a pole of digital transformation will be built; in Ribabellosa, a gigantic data center; in Donostia, a quantum super computer; and in addition, artificial intelligence is in force with its army of hardware and semiconductors. How many metals, how many minerals, how much cobalt will it take?

The phrase that heard the girl from Lake Malo has been engraved in the head to Ferdinand Lassalle on her return journey. Bodies were merchandise and merchandise in the Congo. From Katanga he has addressed Yagambi in a British aviation biplane, from Yagambi to Kinshasa in the steam, then in the cupboard, and has finally reached the end point, to the alley between the Lumumba and Shuman streets of Brussels, dzart and klak, without realizing that it is also the beginning. But this is not a novel, this is a reality.

Energiaren Nazioarteko Agentziak (IEA) astelehenean argitaratutako txostenaren arabera, %2,2 igo da energia eskaria 2024an aurreko urtearekin alderatuta, besteak beste, egiturazko arrazoi hauengatik: beroari aurre egiteko argindar gehiago erabili beharra, industriaren kontsumoa... [+]

Eusko Jaurlaritzak eta Arabako Foru Aldundiak Datu Zentroen instalazioei ateak irekitzen dizkiete horiek arautzeko legedia sortu aurretik. Bilbao-Arasur Dantu Zentroarekin, bere lehen fasea gauzatuta, eta instalatzea amesten duen Solariaren Datu Zentroarekin, 110.000 m2... [+]

Espainiako Estatuko zentral nuklearrak itxi ez daitezen aktoreen presioak gora jarraitzen du. Otsailaren 12an Espainiako Kongresuak itxi beharreko zentral nuklearrak ez ixteko eskatu zion Espainiako Gobernuari, eta orain berdin egin dute Endesak eta Iberdrolak.

The Centre Tricontinental has described the historical resistance of the Congolese in the dossier The Congolese Fight for Their Own Wealth (the Congolese people struggle for their wealth) (July 2024, No. 77). During the colonialism, the panic among the peasants by the Force... [+]

The update of the Navarra Energy Plan goes unnoticed. The Government of Navarre made this public and, at the end of the period for the submission of claims, no government official has explained to us what their proposals are to the citizens.

The reading of the documentation... [+]

Environmental activist Mikel Álvarez has produced an exhaustive critical report on the wind macro-power plants that Repsol and Endesa intend to build in the vicinity of Arano and Hernani of the region. In his opinion, this is "the largest infrastructure of this kind that is... [+]