In the name of green capitalism, criminalized by land defenders.

- In 2023 we learned how far the power of the Russian Swiss multinational Solway Investment Group came. A journalist from the Community Press informed us of an investigation that revealed the abuses of the Fenix mine it has in Guatemala, and the multinational tried to censor that conversation by demanding its elimination and payment of EUR 15,000. ARGIA took advantage of the aggression to defend independent journalism. We now know first-hand the human rights violations generated by Solway's extremism: environmental pollution, criminalization of the defense of indigenous peoples, threats, attacks on journalists, bribery... Given that the Western multinationals want to silence the pain, fear and destruction caused in Guatemala, we have given a voice to the organized communities working in the defence of the land.

In Euskal Herria, we are increasingly rising to the proliferation of macro-projects, concerned about their damage. But how far are we going to defend the environment? The Maia peoples we have known in Guatemala have no doubt: they are taking land defence to the end, because life is at stake. Unlike most Westerners, indigenous peoples coexist with nature, they are their vital sustenance and land and water play a fundamental role in their conception of the world.

What is the relationship between climate change and human rights violations? NGO Mugarik Gabe concludes in several reports that there is a close link, among other reasons because in Latin America the same pattern is repeated in many countries: “The extremist, capitalist, and neoliberal model is systematic, guided by colonial logic and sporadic.” It is therefore clear that we are protecting the land by defending the rights of peoples of origin. The NGO is calling on the institutions to take responsibility for the development of their functions. “We need to focus on the companies and entrepreneurs most responsible for the climate emergency,” they say. Thanks to Mugarik Gabe we have travelled to Guatemala and we have known the struggles of the Mayan population suffocated by extremism.

Alta Verapaz is the largest macro-project department in Guatemala. In turn, this department is the one with the highest extreme poverty in the country, with a poverty rate of 83%. In the villages that we have crossed the rugged roads there is a clear lack of basic needs, as electricity does not reach everywhere and food is more or less abundant depending on the harvest. In addition, there are isolated communities that have been unable to access them because of the closure of roads due to the rains, and because some roads are owned by hydroelectric companies that need their authorization for their passage. Of course, they don't want to find journalists on their way.

Two of these hydroelectric plants are located near the capital of the department of Coban: Renace and Oxec respectively. The indigenous leader of Maia q’eqchi’, Bernardo Caal (Santa María Cahabon, 1972), stresses that “killer capitalism” has a great interest in Alta Verapaz, because there is productive biodiversity, among other things. He is well aware of the practices of multinationals, as in 2018 he was sentenced to seven years in prison for fighting these macro-projects without presenting evidence. Charged with theft and unlawful detention, Amnesty International has recognised him as a “prisoner of conscience”. He has spent four years in Cobane prison and, because of his good conduct, he was let out. From outside the prison he has told us that he was helped to survive the prison, to continue fighting and claiming and to receive 50,000 letters of support from the citizens. Noting the Cahabon River, which passes 300 metres from the prison door, he recalls that he listened to the river inside, which gave him strength to continue to defend his flow.

Caal accuses the owners of “green energy” producing companies and the governments that are accomplices to it of “ecocide”. It describes nature as being: “The hydroelectric plants torture, massacred and kill the Cahabon River. Where does all the wealth they bring out go?” he denounced, recalling that the energy they obtain from it is not for the communities, but is generally destined for mines and other macro-projects. To illustrate the size of these plants, it should be noted that the Renace and Oxec hydroelectric power plants produce more energy than the State generates. To do so, Caal has warned that the river dries because, in order for the plant to function, it diverts the flow towards artificial channels of 8-10 meters depth. After all, they privatise water and the river for economic gain.

The entrepreneur has no hair in his mouth and says that the culprits must be pointed out: The Spanish businessman and president of Real Madrid, Florentino Pérez, says that he is acting as “criminal”, as his company is ACS, owner of Renace and part of Oxec. He has also pointed out to an Israeli company that owns the latter, that in times of war he arrived in Guatemala “to get millionaire projects” and “to do scams”. However, Bernardo Caal has shown that these transnational corporations can be tackled: “Florentino Pérez’s company had seven licenses to build power plants, and when they were in the fourth phase, they put me in prison. But thanks to the help and struggle of many organizations, the others were paralyzed.”

Cahabon is one of the most important rivers in Guatemala and Caal is clear that he will continue to defend: “Cahabon goes like a snake, zigzagging, joining the rivers of different peoples. It is the union of numerous rivers that, after many miles, lead to Lake Izabal.” The indigenous leader continues to believe in the fruits of exerting pressure through the organization, although to do so he has to take risks. The prison has not silenced it, but it has ensured that its case has international prestige and support.

From hydroelectric plants to mining plants

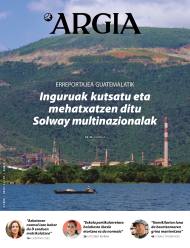

The zigzag of Cahabon is directed towards the east of the country, towards the heat of the Caribbean Sea. Over the many plants, Cahabon joins the Polochic River at the entrance of the department of Izabal and pour the flow into Lake Izabal, the largest lake in Guatemala. The waters of the lake, 45 kilometres in length and 20 kilometres in width, have been very busy in the last decade and contaminated by the effects of extractivist macro-projects. As we have been told by the surviving communities of the lake fishing, the Fenix de Solway mine and the palm plant of Naturoils, S.A. contaminate Izabal, among others.

Izabal is surrounded by an idyllic landscape for tourists: high green chains, wild nature, free animals, birds in the catch of stripes. The lagoon is so big that it's hard to see the other end of the land. But there's something you can see from any point on the lake at the naked eye: a piece of naked, colorless green, brown-orange dyed. “There’s no more anterior hill, it’s an egg shell, like an egg without yolk or clear,” a fisherman describes. And underneath this naked mound, on the shore, there is a fireplace and gigantic constructions with the Pronico, the nickel processing plant used by the Russian Swiss company Solway Investment Group.

Pronico, CGN and Mayaniquel are the ones who are taking out nickel and have tried, like other entities, to explain it so that sanctions against one or the other do not affect them. But basically, they act together and they're linked to Solway. As Paolina Albani told us in the 2023 interview, “they behave like criminal organizations,” even taking their heads off, another will come and will continue to remove nickel “because it’s profitable.” Faced with the sanctions imposed for breach of the law, they have always denied what they are accused of, and emphasize that they are “sustainable companies”, that collaborate with the government and the Guatemalans, and that they generate about 1,500 jobs.

Who has polluted the largest lake in Guatemala?

The usual practice of this multinational that tried to censor ARGIA is to suppress all voices against it, as we have seen from there. The mine is located in the fishing village of El Estor, with about 80,000 inhabitants, and more than 90% are of Maia q’eqchi’ origin. The company has the entire mine environment under control, and maintains constant surveillance from land, air and water. It is therefore not easy for journalists to get there. Juan Bautista Xol (El Estor, 1994) We moved to El Estor with the journalist of the Community Press. From the outset he has lived and counted the fight against the mine, and to report the case he is being persecuted. “The communities that you see by the road are the ones that lived on the first mountain, but were displaced to extract nickel.” Bautista explains that many times companies use money to displace communities, and other times violence or intimidation. Later, protected by a large lockdown, he has taught us the domicile of the company’s workers who come from outside, what is known as “colony”.

The closer I get to the plant they process, the worse the road is. “These holes have been caused by the transit of their trucks,” said the journalist of El Estor, pointing to the fireplace and adding: “When they were processing nickel, the smoke from the fireplace raised a red cloud every day.”

At the moment, this plant is not operational, among other things because in November 2022 the U.S. Department of the Public Treasury frozen its current accounts, due to the activities reported. However, this sanction was lifted in 2024, and Solway announced that work is being done to get it back on track. Work is also being done on the extraction of so-called “rare earths” containing some minerals, but their influence on the people cannot be compared to that of fireplaces when they are operating. It is a nightmare for the people, who are living with uncertainty when it comes to putting it back on track. The information offered by Solway is very opaque and the population does not know its intentions. In this way, it is also easier for him to act with impunity.

On the shore you see large piles of waste generated by the mining operation. The company says they treat them so they don't become polluting, but many fishermen have assured us that they don't. “They do not comply with the environmental impact report. They've dried up the hill and polluted the water. Fish have decreased. Before we took the hook and took a fish, now we didn’t.”

As has already been mentioned in previous articles on Solway, in 2017 there was an explosion of the case when a reddish spot appeared on the lake and fish emerged dead. It was then that the Fishermen's Guild was created and protests hardened. The company claimed that the contamination was due to marine algae that were responsible for the contamination and attributed the blame to the population. However, according to the large international journalistic study Mining Secrets, the company concealed the contamination and used all kinds of practices to silence what happened: threats, intimidation, bribery... Moreover, during the protests, the Police shot the fisherman Carlos Maaz, arrested by the police.

Organized by fishermen against the mine

The situation has become completely undermined, and since then they have been involved in violent criminalisation and repression. We have been told this in the plenary session of the Fishermen's Guild by a dozen women and a fortnight of men invited by the Community Press, who have asked journalists to tell us their reality: “When you come, the company and the government bother, but if you don’t count everything, it’s covered.” Until now, they have felt “abandoned” by means other than the Community Press. They criticize that the power of the company reaches everyone, and that it has purchased media, armed forces, government, mayor, judges... and representatives of indigenous peoples.

“We are at a critical time, the tension is great.” The members of the Fishermen’s Guild speak from indignation and indignation, interspersing the Q’eqchi’ and Spanish language. And it's no less. Violations of the rights of indigenous peoples are ongoing and have been condemned to live in the exercise of power, with fear, anxiety, mistrust and helplessness. The organisation and solidarity are the ones that help them to move forward, but they have recognised that for lack of resources it is difficult for them to maintain the AIDS network.

You recalled that on 29 October last, another colleague from El Estor was also killed, the fisherman Felipe Xo Quib, also of Portuguese nationality. A worker of the mining company has been charged with the murder in the Fishermen's Guild. The widows of the two fishermen are in the plenary, the children on their knees. “Who will compensate these women? How are the children going to get ahead?” The blacksmiths have called for “justice”, and have reaffirmed that there have been no injuries.

Violation of the right to consultation

The members of the Fishermen’s Guild have two main requests: to investigate human rights violations and Solway’s action and to give effect to the legal right to consultation. The right to a “well-intentioned” consultation is one of the main demands of the Mayan people. Therefore, before authorizing the implementation of a macro-project in the territory, the State should consult the countries of origin, which should be prior, free and informed. In Guatemala they have two tools to demand that this be guaranteed, which the Government has approved: the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169 on Indigenous Peoples, signed in the 1996 Peace Accords, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the Government in 2007.

The Fishermen’s Guild asserts that a “well-intentioned consultation” would accept the result. However, there have been no cases in El Estor and other communities in Izabal. The Constitutional Court of Guatemala ruled in April 2022 that the Fenix mine, consulted in 2021, was not legal. The judgment stated that the company should stop its activity until further consultation, but there is no date for this. The president of the Fishermen’s Guild, Cristobal Pop, was imprisoned for the defense of the lake and has denounced that the 2021 “was not a consultation”: “The communities did not allow the installation of the mine, the interrogation had no information or freedom.” In fact, the fishermen have warned us that at the time of the consultation he was in a state of siege in El Estor and that the company used the bribe to obtain votes to favor.Otra of the causes of the tension that live in the village is that the mine has created conflicts and sides among the population.

Some have even spoken out in defence of mining. The fishermen gathered in plenary are leaders of the Old Authorities – the organisation of indigenous peoples and self-government – and say that the COCODE organisation – auxiliary mayors –, which brings together representatives of indigenous peoples, is committed to the mine, rejects them. They have assured that some have lived in the first person to have been auxiliary mayors and to have suffered bribery, but by refusing to do so, now, as old authorities, they feel marginalised. In the 2021 consultation, for example, certain COCODE interrogations were summoned and former authorities were excluded. “We regret that collaborating mayors and mayors sell themselves. Indigenous people should not sell poverty.” Another, looking at the neighboring lake and the fertile lands, added: “We are told that we are poor, but look at this, everything is wealth.” Guided by the fishermen of the Gremio

Cristóbal Pop and Juan Bautista, we have crossed the lake Izabal by boat and we have reached the community of Chapin Abajo on a one-hour journey, at the speed allowed by the old engine of the boat. As we approach the shore, we perceive a strange smell. “It’s the smell of the NaturOils plant, palm oil,” says journalist Juan Bautista. This community is isolated because they cannot leave it, as several members are criminalized and have arrest warrants to fight against the impositions of palm plantations. However, we have found an organized community “against capitalism and neoliberalism”, as the explanations of the indigenous leader Pedro Cuc have made clear to us. Among other measures, half of the land that Palma had occupied without consulting, cutting palm trees on its own and diversifying the harvest has been recovered. They have been doing so for a year now, but they are still grieving: they are surrounded by police forces that have suffered severe repression, violence against adults and children. However, they are hopeful in the struggle for the fulfilment of their mission: “All we want is to give our descendants land and habitable values.” The attempt to censor the voices of communities begins with the sunrise, and this is how the umbrella networks launched

the night before are being collected. Fortunately, the wives of many of these men will sell on the beach or on the market what they weigh on the net, until child care jobs do not prevent it.

John the Baptist is the father of the journalist. The journalist worked for five years as a victim's aide, at a time when he began to report and report on illegal fishing. They are artisanal fishermen in general in El Estor, and they are very far from the industrial fishing so usual in our surroundings. His son Bautista discovered that traditional fishermen needed a voice and found the way to claim on social networks. “I am not a journalism graduate, but I am a community journalist,” said the Communist Press contributor.

It has paid a heavy price to be a community journalist, that is to say, community loudspeaker. A number of community journalists were targeted by the company for following the anti-mine protests in 2017, and had to flee it. Bautista was not yet a journalist, but he felt “obliged to inform the public” and began working for the Communist Press from Eastern Europe. In 2021, the company carried out a strong crackdown on land defenders, who blocked the road, and Bautista reported it. The answer to the information was that they entered their home for six hours, they removed the electronic material... He then fled for 45 days to “protect his life”, and upon his return he found that the mother of the two-year-old and her partner at the time had also managed to attack the journalist with the bribe.

He is now the only Community journalist in the town, and he has criticised the fact that the authorities have difficulty working and denied him information. However, the gratitude of the communities motivates him to move forward and it is clear that he will continue “to the head” in this work: “I have persecution and targeting against me, I am afraid to enter and leave the house, but I have not moved from my people. Because if I go, who is going to do journalism?” In defence of freedom of expression, various workshops are being held in the surrounding communities so that citizens can learn to tell independently what has happened, without waiting for journalists.

Bautista's parents support his work and that also helps him not to give up: “My parents are part of the resistance of the territory and thanks to them I am here. I’m not going to leave it, I may one day get censored, but on my own I’m not going to stop telling

the reality of East.” Information about the excesses of extractivist projects to reach the other side of the sea is often against the wind. On the contrary, Europe opens the door to the oils and nickel extracted from the palms and the mining plants, and large companies and shops welcome the loaded boats departing from Puerto Barrios in Izabal.

In 2025, at least one journalist was murdered in Guatemala and another disappeared. It is dangerous to do journalistic work in this country, and so has Reporters Without Borders, in the World Press Freedom Classification 2025, published on May 2. Guatemala ranks 138th out of 180... [+]

A Western multinational exploits the natural wealth of a territory considered “third world” on a massive scale. Money for the company, pollution for residents and various problems. How many times have we heard this story? On this occasion, however, 65 journalists and... [+]

Martxoaren 8an legearen alde bozkatu zuten, baina presio sozialaren ondorioz martxoaren 15ean artxibatzea erabaki dute. Abortatzeagatik kartzela zigorrak handitu eta eskoletan sexu-aniztasuna irakastea debekatu nahi zuten.