"Literature is a place for complexity, not for lecturing."

- Uxue Alberdi has just published his seventh work for adults, the third in the story: Hetero (Susa, 2024). The book contains eight narratives, and the starting point of all of them has been a landscape, a moment or a relationship that has made him stand in the memory and think “I have to write about this once”.

It's been eleven years since Euli-ambiente -- your second book of stories. I have clearly noticed the bleeding.

In recent years, I have made a conscious effort to learn how to read and write better. The first book, Aulkbat elurretan (Elkar, 2007), I wrote it at the age of 20; I had a great passion for reading and writing, but I was writing by the touch. I was really excited, but I didn't know what I wanted to write. In creative processes there is always a palpable phase, necessary, because we have to walk along unknown paths. But as I read more and better, I've tried to fine-tune my tools and intentions. In the fly environment, I started from a few ideas or sensations, and I didn't know where I was going.

In Hetero, before writing, I've done a great approximation job of taking notes, doing memory exercises, looking for narrative structures, collecting material. I had some stories I called -- dynamics between characters, landscapes, languages, scenes -- and I've looked for the most honest way to tell them to me. And it's been a joy. I've written eight stories in three years, but equal to 500. It's hard to look back at evolution itself, but I think they're more conscious stories and a much broader reader journey.

In the books published since Euli-giro, hearing is very present.

You say ear, and I don't know how they'll tie up, but I think it has something to do with it. I think books about the fly environment are more daring. In the work I had carried so far, I hid more behind the words. Writing can be curtain or window. It really seems to me that the first condition for telling something right is wanting to tell, daring to tell. Technical-artistic resources can be used to show or hide in any artistic discipline. Showing is scary, but I admire writers who dare to show their mess above their fears. We are all chaos, no one is absolutely sure of anything; we all have contradictions, we are all amulets and beautiful. That is why I think it is important that people dare to tell us something about the risk of taking us, of disagreeing with us, of enjoying ourselves and of not enjoying ourselves. I think I started to be more daring in Jenisjoplin, and I dared to say that in Gorge Contra, in Dendaost and in Hetero there is this movement. What do I want to tell you? What impresses me? At first, I heard inside myself.

He's put the title Hetero. How have theoretical readings influenced your work? To

begin with, I must say that I would not dare to put the title Hetero to this book if it was not for you. That is the case. As he delivered the stories to Leire [Lopez Ziluaga, editor of Susa], he was shamed to say: “It’s very heterogeneous.” There was a way of saying it. “This is what has come out of me, but I realize it.” After a while I thought: “What if this is what these stories are telling me?” So I looked at them from another place. I was creating those stories as I asked the inside, and when I met the title, I was simultaneously raised by fear and concern. It's a powerful title, quite flush. He laid you down against the wall. It is not the same to put in a book The water that touches us, all the ages of Man or Hetero. The others could be beautiful, symbolic, but they didn't say much, they didn't project a specific light on the collection. Hetero does. Reading Hetero, I think we all get a little bit alert. What do you mean by this title? I was also afraid, because I knew I was going to have to talk about the title. But inside I was saying yes, with everything I don't understand. This title is not very controlled. There are things I see, and there are blind spots that I haven't been through my body yet. Writing, to me, is a way to get things moving that I still don't fully understand, emotions that I don't quite master.

My blind spot with the title has to do with heteronorma: when you're in a system's power place, you don't have to think so much about it. I thought a lot about the invitation that McKenzie Wark makes to think about Love and money, sex and death, translated by you, rather than being straight. In fact, we first associate heteronorma with desire, but it's a lot more. And I think that even though we keep going to bed with the same person or similar people, we can do it more hetero-minus hetero-and there can be movements beyond the bed.

"I think it's important to risk saying even the danger of not wanting to do something grounded."

It is a political regime.

Yes, and a drill, a theater, an economic and psychological structure… I try to be more and more conscious when and in what way I am playing the hetero. I'm waiting, nobody asked me yet: Are you heteronous? I've thought a lot about that, about what I'm very heterogeneous and about what I think I'm not so heterogeneous. What have I become unheterogeneous and what not?

In the book, many of the characters fall within the heteronorma, both in sexual affective relationships and, for example, in relationships with parents and biological, cultural and political parents. They are heterogeneous in the relationship with authority. Thanks to transfeminism I have tried to make some movements of de-hetero-culturality: I do not pass my work to the cultural parents for the contrast, I do not seek authority, but I try to share my tools and the cultural capital accumulated with the sisters, and I want to listen, read, understand my female colleagues, mourners, maricas, to put me in the collusion with them.

"We have to know the language of writing, know its power and possibilities, see where we can get dirty or break"

Many of the nodes in stories are also related to heteronorma.

Yes. Many characters are tense between two opposing forces: they want to kill their father and keep their father alive, they are uncomfortable but do not leave the game, at the same time they want to be there and not be there. In the story “All the ages of the human being”, a family appears that wants to keep its father alive and strong. They organize a swimming challenge for the father and his two children to participate, and the family prepares everything for the father to win. The daughter feels great relief when she sees that her father can still defeat her, she gets something loose in her chest. I wrote this story from the impression that my father's old age gives me, but if we open it to society, isn't the game always what the father organizes to win?

Despite these more theoretical readings, it is not a book panfletario.Un friend writer wrote to me

as soon as I finished the “Literary Lessons”, telling me that it seemed like a shredder: “I have hated the editor, I have hated the writer and I have hated myself because I have felt identified with him and I have become entangled in this kind of relationship.” As for this story, the editor has nothing to say, but the writer is not linked to the editor from a place he can presume. I was writing from the opposite throat, I had a head full of feminist theory; I knew the theory, but I fell the same. We chained ourselves in our arteries, in our holes. In addition to the male characters that work for empowerment in stories, I've tried to show what the female characters put into those relationships, instead of pulling them out of the equation.

It is difficult to show the flirtatious face of despoderado.Cuando we talk about rupture or overcoming the nuclear family, when we criticize the heteronorma, as in many other struggles, one thing happens: what we want to overcome or break or change has

built us, about that we live some more than others. We need politics, we need theory and slogans, rigorous thinking, but literature doesn't have to be a place to tell how things should be, but to complete and teach them. How do we move? What happens in our inland waters? How do the characters love it? How do you want it? What do you want, but what do you do? I think literature is a place to be complex, not to give lessons.

For example, in Annie Ernaux I read Pure Passion and, to begin with, I get angry with the title, because for me it is not passion, it is an obsession, a chaining and a sick place; and at the same time, it seems to me an amazing book. Reading I suffer, my head just screaming at the narrator, it doesn't matter! But why did Ernaux write? It was because he hadn't left. And it's important to say that feminists also engage in asphyxiating, powerful relationships, that our love is not pure, that we all have holes. No one is independent, we're all dependent, and it's important to have all of that feminist literature by hand. But more important are the good friends who will tell you: get out of there. And give it to you for that time.

The way storytelling characters play is not exemplary, but at the same time they are not so blind as to be comfortable. On the other hand, within this hetero framework there are also characters who love and feel tender, who due to difficulties exercise mutual care.

I don't want to end the conversation without mentioning the work of language. The home brand is rigor and wealth in your case, but this time it seemed to me that it has taken a step further, especially in the “Water that touches us”. “The water that touches us” is,

in a way, Jenisjoplin’s precariousness. It's been a joy to write. I wanted to capture the soundscape of our adolescence: what tells us how to talk about characters and times. The stories are written in unified Basque, but they are dotted in Basque, in western Basque, in sukalki. For me, it is very important that the language is well-focused — syntax, the stream down — that it knows how the Basque language works. Language is a living animal.

We have to know the language of writing, know where the air is from, know its power and possibilities, see where we can get it dirty or break it. I think there are a lot of books in Basque that have nothing of Spanish and that, in my opinion, are miswritten. I say bad writing because the language doesn't dance, it doesn't say anything, because it's cardboard. Instead, I think what we needed to bring the novel Pleibak, by Miren [Amuriza] Pleibak, to the next phase. I think he is one of the writers who best knows how to listen to the Basque, has an impressive ear and, precisely because of that, he can include phrases such as “a pollalapiz has come to me” or “these have always been some notes”, because at the same time he tells you “a narrative type”. He knows how to build the narrative, and he puts it on you, but when he has to say the debt will say the debt, why can't we say the debt in Euskera in a book?

Just like in any other area, if you know your tool well, you've got a lot more access to freedom. Language can be broken from responsibility or irresponsibility. I think we have to distinguish between books that are written forcefully in Basque, stained, dotted or obligated, but that have movement, rhythm, color, life, hearing… and that, supposedly, are written in Spanish even if they are written in Basque. Very little has been said about this, but I think it is urgent. Doing well in Basque does not mean in cardboard and all the same. Let's focus the tool in depth and then break it as everyone wants, let's play with language so that more people come in, and let's open up the imagination.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]

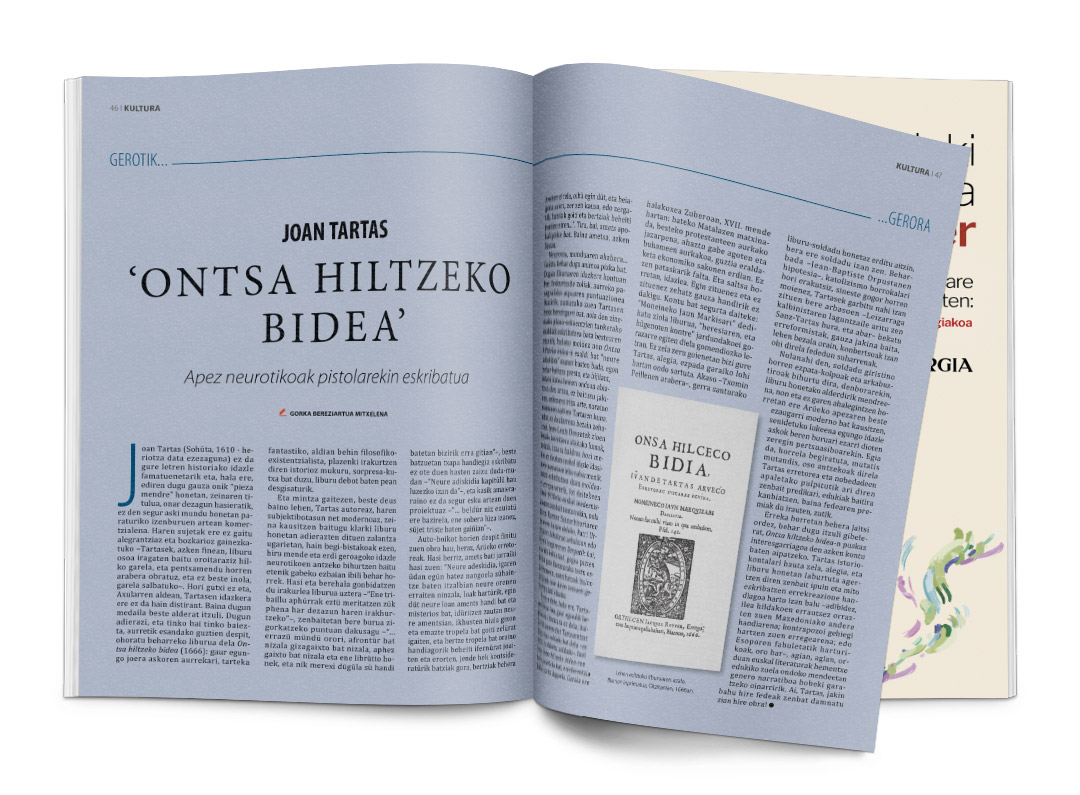

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)