“Change and movement I am passionate about”

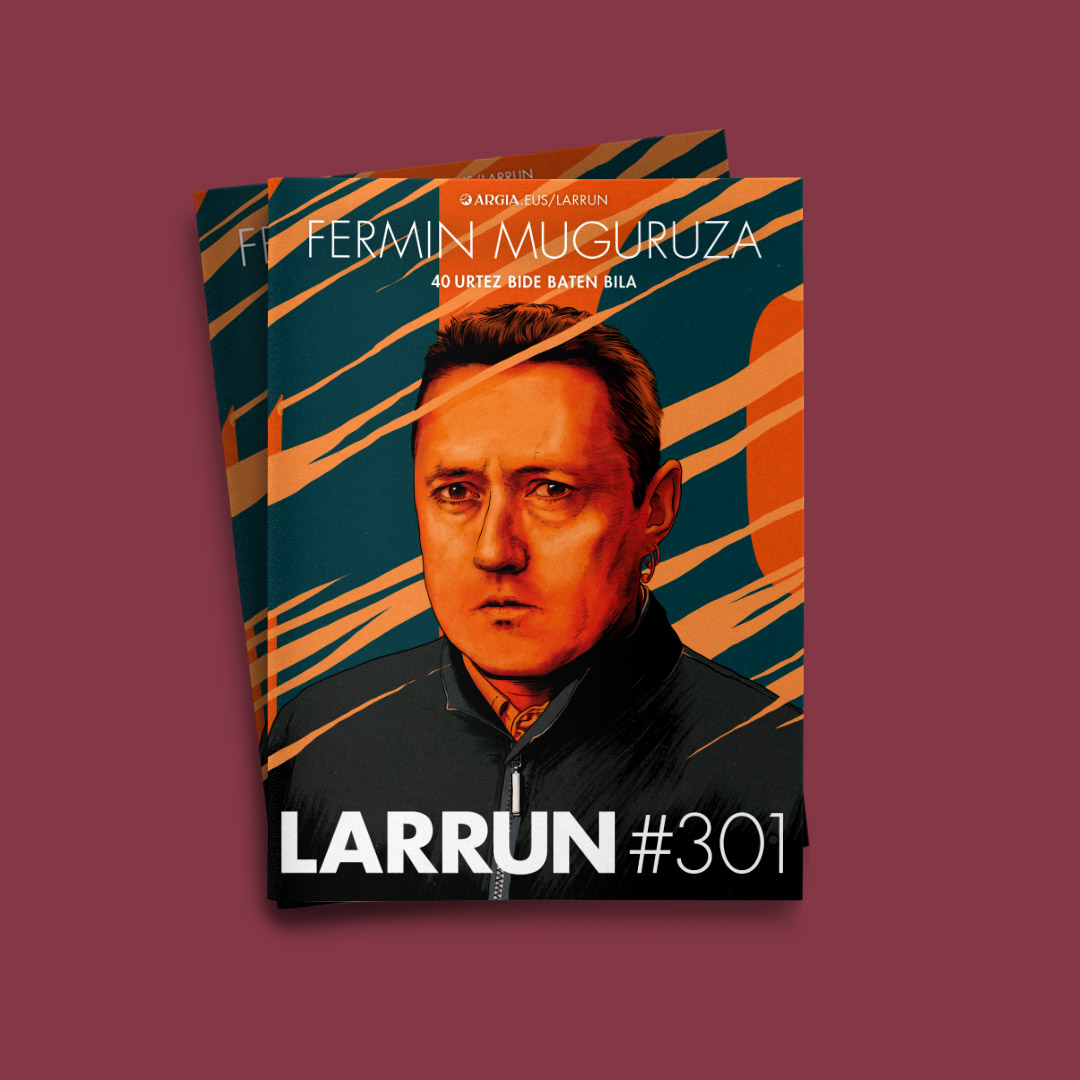

- Fermín was born in the former hospital of Irun in 1963, within the Muguruza de los Ugarte family. He is an artist who has exerted a gigantic influence on Basque music in recent decades. Not for nothing, he has been the singer and alma mater of Kortatu and Negu Gorriak, the creator of the independent label is Ozenki, the musician who has composed nine solo albums… In total, he has offered over 830 concerts in Euskal Herria and throughout the world, since he became Euskaldun, in Basque. “I have always looked for a way: Euskera, self-management... and with my work I have tried to change things. And if things can't change, at least, I've been surviving, advancing and protesting," says the interview we've done at Irun's Kabigorri Atheneum.

In the next lines the reader will be able to confirm that the joy of living unforgettable experiences in the world of music contrasts with the constant persecution that Kortatu has had for more than 40 years by the police and the extreme right. From death threats to attempted attack.

But they haven't shut it down, and they're not going to shut it down at 61. Despite having spent the last few years working on other works – comics, animated films and documentaries – at the end of December he will begin to write a new chapter of his biography, with an international tour in which he will offer all his fortune. Always in movement, always in transformation, we have passed over your life and your work.

You were born in 1963 in the house of the Ugarte. Your childhood and youth time is about the 1960s. What are your memories of then?

I remember my childhood in the Lapize neighborhood, at the entrance of Irun. We were in front of the Escuela Sindical de Formación Profesional and La Salle College, so around our house there were many students, it was very alive, we spent all day in the street. I remember, of course, that everything was in Spanish. I didn't even know that Euskera existed. We went up and down the hill with the reel, we were going to steal dolls or corn into a garden that was up there ... I have very good memories.

When you were five years old, ETA killed the torturer Meliton Manzanas in Irun and caused a gigantic earthquake in Basque politics. Do you have childhood memories of Manzanas?

I can't really remember what happened when I was 5 years old, but there's an expression that my father always said and that a lot of Irun's adult people use: Apples are raining more than when they killed. A rain had fallen that day. After the murder of Manzanas, in addition, emergency situations and arrests, demonstrations, students on the street soon began... However, I have images in my head much later, when the students were coming out with the ikurrina in protest, and taking out an ikurrina meant that the police would carry out their calls right away, screams ...

Where does your interest in music and culture come from?

My father loved accordion a lot. He didn't know how to play, and he wanted to teach us. Mikel Bikondoa was coming to teach us the accordion, who had been the world's champion. I remember asking us for musical seriousness. You could play popular music, but you had to be always very serious. It rejected the way in which the accordion of the French State was played with its vicissitudes, saying that it was not about touching the accordion. I was influenced by the music coming from the east, with an oriental aesthetic, I mean the time when the blocks existed. I have ever talked about this with Joseba Tapia, who has also received classes with Bikondoa. I also went to Bonn to a championship, to Germany, with my older brother Jabier. Despite being West Germany, it was Germany and we saw other ways to play.

Before you created Kortatu, did you walk into social movements?

Shortly after Franco's death I entered the salsa, when we received a hard blow here. Josu Zabala was killed at the Hondarribia festivities on 8 September 1976, coinciding with the Alarde of San Sebastian. I was 24 years old and had an ikurrina embroidered. A demonstration called for the freedom of the disappeared Pertur [Eduardo Moreno Bergaretxe] to reclaim "the total amnesty of prisoners on the street" and the Civil Guard came here. They shot a lot of gunmen and killed Josu. It was very hard for everyone. My older brother Jabier was here, and Iñigo and I were on holiday with my parents in Salou (Catalonia). They called them on the phone and I remember they started talking to each other in Basque, that for the first time I realized that they knew Basque, that their mothers were very few, but that they could speak in a mysterious language, without us understanding it. We turned right away. Irun Municipal Police (Gipuzkoa) had occupied Irun, where the burial was found. My father went to the demonstration and we went to a house to see the demonstration. The police came in very strong, and then I had nightmares about the dogs, which were starting to run behind me and the people. What I saw was like trauma.

The next year, I started military. What was called pre-militancy was done in a movement called Gazte Abertzale Iraultzailea (GAI), a youth movement with a quite libertarian tendency. When we entered the group and read all of Marta Harnecker's books, it faded. In Irun we were a lot of young people, and we were told right away that we had to organize KAS Gazteria, which were creating village groups in town. In fact, when we went to the first congress to create what would later be Jarrai, our presentations were not accepted. We were mainly dealing with two important points: one, unwelded, the input; and two, the legalization of all drugs. They were not admitted and we left. We were three groups in Irun and one followed. I entered the Antinuclear Committee.

You mentioned that of Zabala. It was convulsive times. Repression, state terrorism, armed struggle... Can you cite more events that have marked you in your youth?

Before going to the Hondarribia Institute, I did a year in San Sebastian, at La Salle School in the Loiola district. It was there that María José Bravo happened. She was raped and killed by the Spanish Basque Battalion (BVE), and her partner was beaten and severely injured forever in Loiola. It was terrible, I was 16 and we were the same age. When you're young, that makes you. I remember going to Boulevard to make the demonstration and we were told, “The students have gone with the banner.” We approached us and we got on our way. The police rushed to charge; we rushed out and those who came behind us protested them of rage. My memories of urban guerrilla dance are very strong and I can proudly say that it was absolutely necessary. I've told you that detail, but we've experienced a thousand other events. “Day uniforms, uncontrolled at night,” we screamed and so it was. It has been demonstrated, not only in the Basque Country, that there have always been military involvement or civil guards at the far right, see Lucrecia [Pérez] or Carlos Palomino.

I have a pretty sharp timeline. BVE and other groups, from Franco until 1983, were engaged in spreading terror. Subsequently, using the same structures and mercenaries, the GAL was created for the practice of state terrorism with the PSOE. I remember that the murder of Santi Brouard, for example, was a tremendous blow. Brouard had a great charism. Once it was when Kortatu started. We took the model out in June 1984 and it was killed on 20 November. In addition, the first time we went to Iparralde, [Xabier] Galdeano was killed. We knew it after the sound tests and remember that his daughter came to visit us, saying: “You have to do a concert.” After that, the Mombar Hotel [Josu Muguruza was murdered by the GAL in Baiona Ttipia with four refugees and was saved because a few minutes earlier he had come to a nearby bar]. When you get to live things like this... Imagine how many blows.

(...)

He also talked to me about armed struggle, and in the line of time I have defined it quite well, that in 1979, when we were 16 years old, there was a movement and a strong debate about whether the armed struggle on the Abertzale Left should be abandoned. So, for example, the polymilias [ETA pm] abandoned it. There was a group, including Sabino Ormazabal, from the Gladys del Estal crew, who said that the armed struggle had no way, that if we had not to fight, for civil disobedience, and that, as we were organized, we had to do it. They went to the bridge when we were in Tudela and said, “Don’t start throwing stones, we’ll cut the bridge and if they stick us, they’ll stick us, but we’ll stay here.” They were placed in the front line. The Civil Guard approached the area and shot Gladys in the head, who refused to shoot. That was a tremendous lesson for us, and we said, there's no way for that, there's a way for armed struggle, if not, they'll kill us.

Then I recall that it was a continuous noise that was called sabre noise and that in 1981 an attempt was made to give a coup d'état and tanks were taken out in Valencia, in an operation in which the king of Spain was also involved. When I turned 18, The Clash came to the velódrome in San Sebastian and, at the same time, began the hunger strike for anger, led by Bobby Sands, which left ten dead. We even knew the names of the dead. I remember we were at the Hondarribia Institute and we were leaving the Institute in demonstration every time a prisoner died. These things mark you and they influence what you're going to do next.

Kortatu was born in this environment. In four years you offered almost 300 concerts and created four albums. What was your life like?

Very intense. Before we started Social Vomiting, the group of Victor Pérez, my close friend, and then we started and Anti Reg, then Bada, Bolingas Anonymous... There were lots of groups in Irun, and the epicenter of the city earthquake was here, in Moscow Square. We lived in the street, and here we met, we walked together. In Kortatu's time, it was very clear that we had to get on the camper and move outside. We slept very little, partly because I slept little by myself and then, of course, by amphetamine. We used to be sleepless days; what's more, sometimes we'd give a very distant concert and we'd come home, listening to music, talking without silence -- I remember there was a lot of intensity.

I'm going to give you an example of how we lived. In Hondarribia, the fishermen went on strike and closed the two spigons. “Here are a lot of fishermen, what are we going to do?” he wondered and answered: “Let’s go to gaztetxe to do a concert for the fishermen.” That's how we went. The gaztetxes they were dealing with were from village to village and we were there, always willing to go and play. So, we met a lot of people, the idiosyncrasies of each village, the assembly of young people of each village, the problems of each one, we help to create free radios and fanzines...

They began to leave Euskal Herria very quickly.

We then began to turn to the North, from there to the French State and then to Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands; and to the South to the Spanish State. We received great lessons. In Barcelona, for example, we knew a very strong movement around hardcore and how the anti-fascist movement was being organized at the “red waistline” of Madrid. In politics, we knew what organizing and fighting was, but then we knew what that was in the music world. We saw that in the French state with the independent record companies. And when we went to Holland, we met The EX. They were a group of independent labels, but they also published works by many others. They were an inspiration to later make Esan Ozenki. We were in their house, they lived together, they had studio, warehouse, room for guests, we were rehearsing -- we were flirting a lot. What did we do in those five years? Learn, fight, get in every mess, write songs, give concerts, listen to music...

You were 21 years old when you created Kortatu and you gained success very quickly. You sold over 100,000 copies of the first album. How did they manage success? Did you have your feet around the people who kept you on the ground?

Yes. We were a crew of Christ, we were in the neighborhood, and the neighborhood does not recognize privileges. Let me tell you a ridiculous anecdote. We went to a nightclub on Irun Fuck Street and they never let us in. At the door there were two thugs who knew how to leave wood and we, in case, hid very quickly. But fundamentally, they don't let us in. And once we went, we heard from the outside that in the disco they had put Kortatu's music. We said, "I! You are putting our music, it’s us,” but they didn’t believe us and sent us to the freak.

That is, we didn’t get too far in the head about “uau, we are famous”, especially because we played with many groups. We, in the early days, those of La Polla took us to Galicia and those of Barrikada to Madrid, and we helped them to make the way to posterity.

Although Kortatu mixed a festive and vindictive atmosphere, songs related to the Basque conflict have a special weight. Were they afraid of the police and the extreme right because they were warming the environment?

This occurred mainly in the 1990s, with the denunciation of Galindo. That's where we started to become aware. But before us, we were moving forcefully. Look at what happened to us in 1986, I've never told you. Iñigo [Muguruza] lived in Hendaya, at a time when the border was fully militarized: gendarmes, PAF, National Police and Civil Guard were on the bridge. The day we were going to play at the Moscow parties, as we passed the border, they got naked and humiliated. They had plenty of time to keep them and at the end they said: “Come, go here and now go and tell your brother to offer us, as always, Jimmy Jazz, that we will be there.” The square was full up and Iñigo, of course, wanted to finish, was angry, you have to understand how we hated the police – that was where we joined all the groups, we all had the songs against them, they hated us and we hated us. I went up to the stage and started. “For all those sons of whore, the dogs have told us that they will come and here they are, be careful, this is for you... Jimmy Jazz!” I'm sure they were there, but it starts to do something -- if you take out the gun, you're going to cause a massacre, but you're not going to survive. Imagine what the atmosphere was in the Basque Country in the 1980s. It was hard. And also, amphetamine is a swell of fear, and I think that also influenced how we went out on stage, or unconsciousness, or youth -- and as Hertzainak said: “War on the State, war always.”

I'm going to tell you a new story. Last year, in 1985, before the Sarri flight, we headed for Martutene. He was in Irun prison [Joxe Mari], in a state of fatigue, and went out a few months later. When we first played at the Moscow parties, we offered him the concert. Two days later, in [far right], in the newspaper El Alcázar, they published an article of Christ against Kortatu. That was our first experience of criminalization. What happened next? The head of the neighborhood community was told by a civil guard who seemed to be a smuggler, "Hey, they're going to get you." Bilili, a mythical one, spent a week hiding in the mountain. Upon her return, the Civil Guard still sought someone to attribute responsibility for what happened to her ex-partner. He finally came to a lawyer, because otherwise he would have been beaten. That was in 1985, imagine what war we were living in.

Three years after you took the first album from Kortatu, you pulled it out in Euskera. Then you've done it all along the way for decades. What have you gained from doing your work in Basque?

I've won a world, I've gathered a world, as we sang in the Big Beñat. We studied at AEK in the middle of a very rich cultural movement to regain the Basque. The race was invented, we crossed the border as the immigrants have gone, we shouted “no, there were no limits” without showing us the card – at that time, we had to first show the passport and then the ID. In addition, the Basque country has given me a great capacity to read, speak, search for words, invent words... To find out all of a sudden that the bullet cap is said in Basque. You take pride in Euskera. Furthermore, I would like to say that I also very much like Spanish, as well as all the languages I have learned: French, English and Catalan. They have all given me a lot, but Euskera has given me pride in being my language, one of the most proud it can have. We were removed and recovered, in our case we were the missing link, and later my children have spoken to my father naturally in Basque. That was a victory.

What do you think when you hear Basque musicians singing in other languages?

I get angry, it's very painful for me. The musicians who choose to sing in Spanish, being all Basques, provoke a cultural shock, the culture shock. How is that possible? I do not understand. I come from the generation that made a great effort to reclaim the language, we euskaldunize the whole crew, we changed our jokes, our nonsense and everything from Castilian to Euskera. With Negu Gorriak for example, in the van we had a great atmosphere. Íñigo and I were Euskaldunberris, Mikel Txopeitia and Jitu were also studying. And we had with us Mikel Anesthesia, Euskaldun zahar de Zarauz, with a wonderful Basque, and Kaki, a Basque scholar. How to better express in Basque the things that helped us all the time. We talked a lot in the van, and if there wasn't a sentence coming out, Kaki gave us master classes. In addition, Kaki and Mikel were tuteing with each other… too much for us!

However, it seems to me that we must also develop strategies of seduction, which happens to me with my son's crew. I arrived and said: “What? Don't you know Basque? What are you doing?” I have given them many times, and well, there you also have to understand that at that moment they want to learn Spanish or French because they have missed several records.

If you're Euskaldun, talk to me in Basque! Sharpen your axes! They were singing with Duat. Are you worried about the future of Euskera?

Galder, Xabi Strubell and Joseba Ponce belonged to the next generation. We saw some trends that we didn't like, and so we decided to say: if you're Euskaldun, tell me about Euskera. And yes, I worry. When I see a whole crew of Basques talking all in Spanish, it strikes me, but I think they “will soon regain consciousness.” And if not, the next generation will give you wood, because it's cyclical.

However, recently the musical phenomenon of Pamplona has sparked a great debate, by its form of expression, with the Mafia Chill, etc. I found it very interesting, the most interesting thing that could happen to Euskera. Sarrionandia said in an interview that Basque literature needs “the barbarians come” and I took it metaphorically and thought: the barbarians have come to music. I thought it was absolutely necessary, because they confused with different expressions, also the jargon in Spanish, they invented words… and with that they attracted new people. As Jon Urzelai says in his book His Festak, he was given another varnish to the Basque. Or with Hoffe, he mixes the Basque and the Spanish in his collaborations. I'm looking forward to seeing when he also follows the path we did with Kortatu. He has the advantage that he knows Euskera.

In an interview with ARGIA by Garbine Ubeda, Josu Landa and Gorka Arrese: “Sometimes I think people think they have rights to us.” Inside we are in the podcast Kaki Arkarazo told that many saw Kortatu as a “group of the people” and asked them to go to give a concert to their peoples. Could you please tell me that?

It wasn't just at the end of Kortatu, it was a constant. In that interview, I told everyone that that was a burden for us, but well, we've also learned to manage it. I've learned to say no. The same as with the requests for concerts, even when we have an announced tour, in a few days we have received. “We want you or Manu Chao to play I don’t know which day I don’t know which side,” I was told recently. I'm laughing at it now, but I used to take it very badly. At the time, there were people who were confused, and even if I was on every cell phone, if we didn't go somewhere, I would take it wrong. Young groups are also going to be affected, but I hope that there is another kind of understanding and that people are not so square.

After a concert by Public Enemy in Paris, in 1988 you decided to dissolve Kortatu and soon after you founded the Negu Gorriak. In ARGIA, you announced the name of the new group. At the touch of the blacks of the EE.UU, they shouted: “I’m Basque and I’m proud!” You published nine albums with many styles: rock, hardcore, hip hop, bertsos, dub music, ska, sampling, soul, African sounds…

To begin with, we achieved independence. People felt that Kortatu was from the village, and yes, it was, but from then on we had to send in our project. We were clear: we will organize what we want and like us, otherwise we will not. And how we should. If we see that in one place 5,000 people will arrive, we will ask for a team for 5,000 people. We saw that the meters of the bar were calculated very well, but all those people deserved to be respected, because I was going to listen to music, offer you the necessary music equipment, etc., it was hard for them to work. There we created a school, and as a result of it, for example, we started collaborating in the organization of things for Jarrai in the South and for Juventudes in the North. Then I have been collaborating for many years in the RSI.

In that independence, you created Esan Ozenki Records on your record label and published about 200 records.

I have an incredible pride around Esan Ozenki, how we started to pull out groups and spread around the world. In addition, we also published the sub-seal Gora Herriak and as a consequence we started building round-trip bridges: From Argentina we came the All Your Dead group and we were going there, the Enemies went to Mexico, our groups moved across Europe, we pulled records from Swiss Wemean or the Bassotti Band from Italy... Esan Ozenki became a benchmark worldwide, to the point that Massive Attack coordinated a double album with groups around the world to ask for the freedom of Mumia Abu-Jamal and they said they wanted to take that album with Esan Ozenki. And we took it out.

I recently read in a tweet someone about a Kortatu album: “This album marked me dry when I was young and shaped my thinking for a lifetime.” I, too, am from 1985 and, for example, my youth was marked by the records of Negu Gorriak and Esan Ozenki that my father gave me. And like me, there are probably thousands more people. What do you feel when you know you've influenced the mindset of so many people?

I feel there is no spontaneous generation. We were also marked by many groups: The Clash, Sex Pixtols, The Undertones, The Jam, The Stranglers and, above all, 2 Stamp Tone: The Specials, Bad Manners, Madness, Selecter, The Beat… In addition, one of them at its height was the one we brought to Aixerrota (Punta Galea, Getxo, Bizkaia). It was terrible. Niko Etxart, Zarama and The Beat! To me and Kortatu's first battery, Mattin Sorzabal, we had to cook and eat with them sandwiches.

But, well, not only those who were not mentioned, also those of before, Ez dok Amairu or Imanol, when I heard the latter singing [recites everything in memory] “The other day, in the middle of the street, in the center of Benta, in the center of Gran Benta, killed our brother Xabier (...) And how we lived, in the peace of mind. Then I learned what I was saying, in short sentences, like You Trapped Art. In addition, Latin American music (Victor Jara, Quilapayún..), I could mention Rock and roll or Nina Simone. Recently I saw the documentary about him Summer of Soul, he starts playing the piano, starts listening to Christ's speech and gets his goose bumps. And the biggest influence: Otis Redding. For me, hearing it was like receiving something from slavery, sadness, struggle and joy of life. I mean, I've also had those kinds of references, and what do I feel? That I am doing my broadcasting job well. Let's see if the musicians who have received that guess how to transmit it.

If you had to choose a Negu Gorriak album to give it to a person who doesn't know the group, what would you give?

I would give him our attitude. The other albums are collections of stories, but this is a novel, with its introduction, chapter one (The first bullet), last and epilogue.

You also won the battle to Enrique Rodríguez Galindo and claimed “Victory is ours.” What do you think of your name?

How long it made us suffer for eight years, we received death threats, letters, bomb threats at Esan Ozeni... There has been no peace process here, and Galindo is an example of this. He was Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, untouchable, owner of the torturers. But not only that: state terrorism, smuggling, drug distributions -- it's led to a lot of things that we should know. I thought when he died: “This has gone in peace and here are many others who remain in jail.” The Basque prisoners have to go out in the street. We need them at home.

It was also an attempt to attack you. What was it like?

Negu Gorriak played the week after the 2001 Velódromo concert, where some 25,000 people enjoyed the victory in two nights next to Intxaurrondo. I went to Barcelona to give a concert in favour of the prisoners and there they tried to put a bomb on me. Four neonazis were burned in the Sants neighborhood when, by chance, they were exploited by placing a home artifact at the place where we played the concert, and some had to be hospitalized. Two years later, in the trial they said that the purpose of the bomb was me and I am convinced it was a gift from Galindo. These neo-Nazis were well known, one was [Santiago] Royuela, his father had a Francoist group and was accused of placing an explosive device at the headquarters of El Papus magazine – one dead in 1977 and another seriously wounded. His son was part of a Nazi group, Ynestrillas and with whom he maintained relations. Ynestrillas were charged with the murder of Josu Muguruza and I was threatened many times in this way: “We’ve cleaned a raspberry, the second one will be you.”

I'll move on to the stage where you started alone...

...knows what the Civil Guard did to us?

I…

When we went to some concert or to the movies, the kids were attended by a girl from Irun. After a while, she was raped and a pistol was put into her shirt. Subsequently, a woman from Irun was arrested and, while she was being tortured, asked who took care of the children of Fermin Muguruza. Or I remember when Gurutze Iantzi died, the civil guards went to register his sister's house. In Rome, having been together in anti-fascist meetings in 1991, I already had a picture of the group we went to and they told him: “Do you also know that son of Muguruza’s bitch?” and they told him to pass the prayer. I was threatened with death from many places for years.

After Negu Gorriak, you pulled out a record with Dut in 1997, you did a big tour and then you stood alone. Since Brigadista pulled out his Sound System album in 1999, you have done eight more works. The change in musical styles is constant. Have you never been tempted to continue with the formula that guarantees success? Is there no temptation to inertia?

That never happens. Change passion and move, go to New Orleans and turn around previously made songs, mock me with the environment around us. One said to me once, “We want to hear the songs of Kortatu, but as Kortatu did,” and I: “As Kortatu did, when? On the first album, on the second, in Kolpez Kolpe or live, where did we have a wind section and a percussion? What are you talking about?” There have always been people who have wanted to stay with this, but it's my answer, you have to stay with all my journey.

In that sense, I once read you a tweet in relation to your song Klika for the Korrika, denouncing you. Are we more conservative than we thought?

Yes, but not just the Basques. The Klika guy went to the hostile, because he had a self-point. I was in that environment, because my son would make me listen to that music, and I thought we had to. In the year 2000, Big Beñat had its remarkable Big Beat electronic rhythm, and in 2018 we had to connect with Klika with what was happening on the street, so we had to connect with the car and dance hall rhythm. Now the autopoint is fully approved and used by a lot of people. The first distortion, the pre-recorded rhythms or the electric battery were not accepted. When Bob Dylan moved from the acoustic guitar to the electric, for many it was a sacrilegium. Pete Seeger wanted to cut off the guitar cable with an axe and the documentary made by Martin Scorsese starts with the cry of a guy: “Uuuuuudaaaaaaas!” Camarón de la Isla was also a traitor for flamenco purists in Andalusia for doing things differently. Accepting change always costs people, it is not just a matter of the Basques.

How do you see the current landscape of Basque music? Which group of Euskal Herria is hearing lately?

Very excited about: Chill Mafia, Hofe, Ibil Bedi, Tatxers, Broken Brothers, Olaia Inziarte, Eneritz Furyak, Petti, J Martina, Merina Gris, Sara Zozaya, Nakar, Verde Prato, Olatz Salvador, Equipo... I listen to all of them and many others very willingly. I've invited many of these groups to be the first in our concerts.

You've often brought music and activism together. With Negu Gorriak, for example, you offered a surprise concert before Donostia's court to denounce the trial of unmissable partner Mikel Anesthesia. You've also touched in many places and threatened gaztetxes. Do you have any concert that you remember with special affection from that point of view of activism?

Artozki's, for example, was big. When the Civil Guard controlled all the roads, we managed to do a concert. We finished Manu Chao's tour in the first week of September 2003, and I started my solo tour with this concert at the end of September. People took our amplifier and our sound equipment… Leño, a great friend of Pamplona, was in that ear. What happens is, then we have a counterpart: defeat. But you think about the moment, “tomorrow they will arrive, but today we have achieved this.” As Victor Jara sang in Te Memoria Amanda, “life is eternal, in five minutes.”

Certainly, that of the input was another of the strong phases. At one point, they decided that they would not stand trial. Mikel Anesthesia was there and we decided to give a concert to the courthouse as a search and capture order was issued on his truck. But the thing is, we're not alone, but there's an entire community willing to do it in activism. That day, we had 100 people willing to help us. The vans in the Ertzaintza were also there, with the helmets laid, but when we arrived in the van, the young people cut the street, the televisions were there… and decided not to intervene. When it was over, we went off the track. They wanted to file a complaint later on, but it was there.

It was also very nice the last thing we did in Paris, in 2017 by the prisoners, in a truck leaving Montparnasse and walking all the way through the center of the city, was very strong. And finally, the Pre-Penitentiary Center of Herrera de la Mancha, first concert by Negu Gorriak in 1990. That was very big.

Your trajectory is closely linked to the conflict and the political situation of Euskal Herria. In Kortatu you were quite clear that you were in favour of ETA’s armed struggle. But then, in the late 1990s, you took advantage of your political and cultural capital to say publicly that you had to end the armed struggle, when this was not easy and knowing that some would not forgive you. Then you have been on the front line calling for the release of Arnaldo Otegi, and also in defence of the rights of political prisoners. How do you see all the way?

We were also very critical in the time of Kortatu, remember that of Yoyes (his brother Ángel Katarain was our technician and today also is, in this last tour we are accompanied), or that of Hipercor (a few days later we had to go to the neighborhood next door) or that of the headquarters of Zaragoza… but yes, in general, we were in favor of the armed struggle, and also of the peace process. The album Azken Guda Dantza made a gesture to the Algerian table, because we were convinced that the armed struggle was going to end. But that didn't materialize and killed Josu Muguruza when I was in Egin Irratia. He was like a brother. There was also the case of Xabier Kalparsoro and Gurutze Iantzi with Negu Gorriak as we went through Europe. However, when [Gregorio] Ordóñez was killed in 1995, the members of the group joined Begoña Garmendia, councillor and spokesperson for HB in Donostia. I still remember his words textually: “We have to fight political opponents with political weapons.” But we also have to take into account how any discrepancy between us was used, which is why many of us who were against it expressed it internally. That's right, until there's a time ...

I had a speaker, but there were always people who thought like me. For example, in Egin himself, the opinion section was carried by Sabino Ormazabal, and we mentioned before, he already thought that the armed struggle had to be abandoned. I was writing a column in Egin, and I started putting some things -- and the first one in 1995 against the kidnapping of Aldaia and some painted ones. “Aldaya pays and calla” (Aldaia pays and calla), they said, we were immersed in the “Talk” campaign and then, when they killed Miguel Ángel Blanco, in 1997. “Cruel and wrong” I wrote in Egin and asked for a truce, a moratorium, to speak of armed struggle. And yes, it was very hard. Some people took it very badly, and in some places they used the word traitor, and they painted it. But well, then you realize that in this life that word is used very easily. And while I was still collaborating with Jarrai and Haika, and when Estella-Garazi arrived with Haika. After his defeat, my rejection of the armed struggle was very explicit, I collaborated with the civil disobedience group zuzen, and I have to say that in 2004 Segi proposed to do the song of Gazte Topagune, and I did it.

How do you see the racism and fascism that grows in the cities and neighborhoods of Euskal Herria as in the international arena?

It is very worrying. In Donostia-San Sebastian, for example, the very well-organized solidarity dinner has been eliminated: one day a concentration is made with the PP councillors and the following day [Eneko] Goia prohibits dinners. But what is this? In football there are always jaleos and that is not forbidden, but a very important tool that can help calm the disturbances on the street. I believe that a great deal of pedagogy must be done and activated in order to try to help people, especially vulnerable people. In a city like Donostia-San Sebastian, on Sunday there were two demonstrations: one for the dismantling of tourism and the other for the solidary dinners. Very clear message.

You've spent the last few years making music for film, documentaries, comics, animated films... There Checkpoint Rock was a milestone and brought you the offer of Al Jazeera to make eleven documentaries. But I do not want to fail to mention Palestine. How do you bring genocide? How do you see the response from Euskal Herria? A tweet you sent at first opened up a lot.

The truth is that I am very ill with Palestine and I think it is essential to press ahead with the boycott: Boycott of Israel. The tweet I was talking about was the occasion of the first demonstration in San Sebastian, as the communiqué was very warm, neither the boycott nor the genocide. I believe that we sometimes try to achieve the maximum consensus, emptying the demands of substance. I disagreed, and I went to the demonstration without signing the manifesto. We are living in a holocaust, for a year now, and what are the Palestinians asking us for? Boycott of Israel. What did Desmond Tutu ask before he died? Boycott of Israel. The boycott was effective against apartheid in South Africa and the boycott must be effective against Israel. In addition, I would ask for a global strike, a day or two, or a week, why not. We are on the doorstep of the Third World War, we are going to stop everything. I believe it is possible with Palestine. In this respect, at the concert we will be offering in Donostia, we will have the presence of the Palestinian group DAM and I hope that we will be able to bring it.

Taking advantage of the 40th anniversary of Kortatu's first album, you announced a concert in Bilbao, another one later, and you have finally organized an international tour. How do you think about concerts?

As Eider Rodríguez wrote, it is not a nostalgia, but an exercise in historical memory. And I'm sorry. We recovered, as a criterion, at least one song from each album, which will be 33, at least two and a half hours live. There's everything. I recently wrote Ulrike Meinhof for the last song, The Front Line or Kolore Bizia. We'll also take some videos, of the 33 themes there will be about fifteen, to see what work I've done, and for example, in Yalah Yalah Ramallah you'll see pictures of Checkpoint Rock. It's going to be a review, a way of saying, this is all I've done in these 40 years, this is all my good.

What reception is the international tour taking? Do you want to stand out?

I would point out, for example, that in Buenos Aires, in the environment with Milei, now that there is privatization, we will play at the Artworks Stadium. It is a rock temple with a capacity for 5,000 people. Or in Mexico there will be groups that have walked around the country, from Tijuana No, etc., we'll do it on a site for 10,000 people. All tickets for the Berlin concert are sold and it will be in May, playing at La Cigalle in Paris seems incredible… I am very happy because many people have deluded it. Not with as much joy as here, of course, but in the Spanish State, in Catalonia, in Galicia... it has taken very strong. More than 10,000 tickets have been sold in Madrid and over 6,000 tickets have been sold in Madrid. That is another victory.

What about San Sebastian, what to say? It will be the summit of my trajectory. And somehow a milestone for Basque music. He recently announced that there will be a festival and the guest groups will be as follows: Girl Coyote eta Chico Tornado de Donostia, Des-Kontrol de Mondragón, Selektah Stepi de Irun (Bad Sound System) de Palestine and DAM de Palestine, to see if we can bring. As Urko Rodríguez said in a tweet, we want to become our Wattstax and pay tribute to Aitor Zabaleta.

What do you think of the culture of the sold out?

It's complex, but I think it's bad that the artist needs the Sold out. With the pandemic, several people began to proclaim that they had made “Sold out,” when the halls were at half capacity. It made them illusion. Before all the tickets were sold by many groups, or in many rooms all the tickets are sold, but it was not created. The truth is that the culture of the sold out sells exclusivity, so you have to buy your tickets as soon as possible, and that is not one of our values. However, having said that, what has happened to me in Miribilla happens to you. Jone [Unanua] and I looked in the kitchen, amazed. We do not even welcome the fact that all tickets have been sold in a matter of minutes. We felt a great responsibility, people were angry because I couldn't get an entry. And by the time we did the second, I already had the message ready, because in a minute they resold all the tickets. “Today I’m going to start looking at what we can do in 2025.” We said, what can we do against the sold out in Euskal Herria? We were offered St. Mamés, but after two Miribillas, we were clear that we had to be in Anoeta. Let's go to Anoeta to make room for people. Then it has happened to us that we sold about 25,000 tickets, a tremendous barbarity. We have recently opened the second ring with 8,000 more seats. We have tried to make the tickets as cheap as possible, but the costs are gigantic, change the grass of the football field, etc., but we will share that spending with Bruce Springsteen.

What do you think of platforms like Spotify that have gained so much power in the music world?

I read Anari, or we organize something together, or we can't do anything. I have all my music. And I see that Spotify has put a lot of money to make Barcelona the sponsor of the football team and put the logo on the t-shirts, and the musicians who fill it with content pay us a misery. They treat us like slaves or parishes. “Above, parishes of the earth. Standing, famélica legion.” But it's not just that. I think social media is even worse. At Elon Musk, I have the messages all the time, and I don't follow them. That does seem hard to me.

After devoting their whole lives to culture, what do you think of cultural policies here?

On the one hand, it's a shame to see how few creators live from culture. We have created an immense infrastructure network, we have culture technicians, and that is fine, but those who create it are very serious. On the other hand, we do not have Basque cinema related to Basque cinema. We are falling into the trap of Christ, because the politicians dealing with culture tell us that Basque cinema is a great success. It's a lie. We have no Basque fiction, that is very serious. Christ’s productions are coming to the Basque Country, because there are now also economic incentives in Gipuzkoa and in Bizkaia, and they will soon also be launched in Álava and Navarre. They come here to work, they find people here to work, but they are external productions. All in Spanish. And around the story we have an impressive attack, with works like La Infiltrada. But here we come to another topic.

And what can we do about this wave?

It's a very good question, I don't know. I was asked to put some songs on La Infiltrada, and I said no. And do you know what you have done? In this soundtrack they have created several songs with Artificial Intelligence, creating music similar to that of our groups. Those songs have no authorship in the soundtrack, and I think it's serious. And what can we do against that? We are entirely dependent on the Spanish State to produce these kinds of productions, and therefore they will never give us permission if we oppose their story. Anyone who wants to do this kind of film knows that these doors are closed and that it is very difficult to do so. Guk Black is Beltza II: Ainhoa we did it with our means and I am happy, now we have also put it in Filmin. But we've taken this step because on Netflix you didn't want it, it's precisely in the Goya that the far right campaigned against us, and they prefer to put movies like Don't Call Me Beef. Now they're also doing a series for Netflix, and at La Infiltrada, they're starring a Spanish policeman, they're making another similar movie with a pickup, about Meliton Manzanas that made Movistar's invisible line -- but what's this? They know what they do, they want to make up the story and they have the power to act constantly. I'm very disappointed, I've been in the movies for many years and I've seen the situation. There's no way, this looks like Intxaurrondo productions.

And, Fermin, what is your hope today?

As Angela Davis says, hope is a discipline that is worked on every day. Otherwise it would have been over.

Aposapo + Mäte + Daño Dolor

When: April 5th.

In which: In the Youth Center of Markina-Xemein.

---------------------------------------------------------

I’ve made my way to the cheese house with the shopping cart full of vegetables, and we’ve spent the evening cutting... [+]

Poliorkêtês

Kerobia

Autoekoiztua, 2025

--------------------------------------------------------

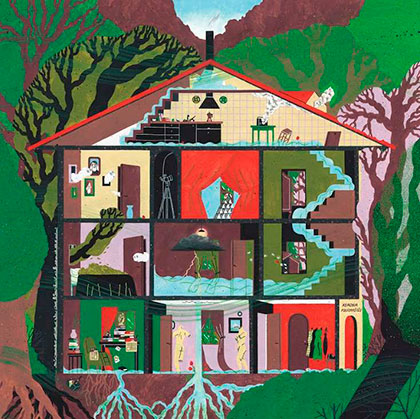

Azken aldian, lerrootan asko nabil hausnartzen musikak izan beharko lukeen “misio historikoaz” eta abarrez. Eta, nolabait, zer egin beharko lukeen... [+]

Under the asphalt, the flower

Text: Monica Rodriguez

Illustrations: Rocío Araya translation

of: Itziar Ulcerati

A fin de cuentos, 2025

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]