"I wonder what working-class women were doing together with bourgeois women in the same demonstration"

- I met Juana Dolores with a motto that said it was more revolutionary to write well than to write in Catalan. I told her I had flipped and she told me it was the first interview of life. Four years later, the wave of novelty emerges and we met him in Barcelona to talk about his artistic work and his political thinking: both very united.

Bijuteria was published in the year 2020, and four years later the Basque translation of Katakrak's hand, Girgileria, has arrived. What has it been like to go back to poems?

I liked to return to Girgileria and, to some extent, to close it – I added a contextualisation text and eight poems, and I have refined some of the oldest – because although in its day the book was very much criticised, in the best sense of the word, there was a mediatisation as a result of my first speeches and political statements, which conditioned all opinions on the work. At the same time, the political and cultural elites exotized me; they were surprised that a Catalan working-class woman, with Spanish names and surnames, won a prize for Catalan poetry [Amadeu Oller Prize].

So, simply, I'm enjoying coming back to my first book of poems, now with more distance between the controversy and my work. I am proud of the Gyrology. I think it's a good first book of poems.

It's got it from the poet's introduction to the world.

I was very clear that it was my first book of poems in general and my first book of poems in particular. I didn't want to go out in a hurry. I needed time and money to do it. I published it at the age of 28; today for some it's a little late. I wanted it to be what the book is: a first book of love poems written and published by a working-class woman, but also finished. I think that is reflected in some verses or in the general aura of the set of poems.

How would you describe the poems you wrote?

I wanted to have a collection of love poems, mine. And in me, my feminine sensibility or sensibility, inevitable and historically conditioned, sometimes ridiculous, but why not, confirmed and shown without complexes in these poems, crosses love. By writing love poems I could not ignore the condition I have as a woman in this class society, characterized by current machismo. But that doesn't mean that the book of poems is agitative and propagandistic, or revolutionary in discourse or content. At that time it was not my intention: I wanted to poetize, aestheticize, "adorn." To do so, I needed a style, a technical and difficult subject. And I worked on this task as I was writing the Gariel.

But I'd like to say one thing, given that we're talking for a media outlet in Euskal Herria. After five years of writing the book, after little illusions and eternal disappointments in political terms – the last poem is called Prayer, and it is no coincidence: I ask God to sympathize with the defeat of men – I introduced a fragment of poems from Vladimir Maiakovsky, known as the “great poet of the Russian revolution”. It says: “You can’t forgive anything anymore. / I have authenticated the tenderness / the souls that raised it. / And it's harder / than taking thousands of Bastillas! / And warning of his arrival / in the tumult of the riots, / you will go to the Savior, / and for you, I / will tear out the soul / kick to make it bigger, / and in blood I will give you by flag.” And so it happened. It was announced that the revolution was still possible. And that's marked me, it's radicalized me. And I took my soul out, and I opened it up to be bigger, and I've bled it like a flag. And so on until the end.

.jpg)

Photo: Amanda Gómez Eleuterio / ARGIA CC BY-SA

The analysis of femininity is present not only in these poems, but also in your last stage piece: Hit me if I’m pretty or modern princess – you’ll introduce it in Bilbao Foundry

on 15-16 February. Suddenly I realized that, to work, I always chose concepts, images, elements, archetypes, stereotypes, etc., female.

Miss, divas, princesses

-- yeah, and that's been organic. But then I realized that at work, I wasn't interested in femininity as an essence, but the fact that I was female as a set of characteristics and characteristics, not only of women. I like to understand the feminine as a vocation, to put it in some way, historical-artistic; there is something that deserves to be studied, that then questioning, denying and overcoming it.

In a poem you say: “Everything that attracts and seduces me builds with proletariat as a feminine value / as an ancient tradition: / ATMs, employees of Claire’s, aestheticians”. I have taken it as a claim.

I do not know if this is a claim. It is a tribute to very feminized professions. Or perhaps just one mention: tributes are often reticent and paternalistic. In line with these verses, I think they also capture some aesthetic influences that the explosion of urban music in the Spanish state has brought to women. That's why I mention them in La Zowi and Rosalía.

But the harp has aged and I too, and there's little of that time left. Self-critiquing, I was fascinated by this new scene – not only musical, it was artistic at all levels – and I thought it was worth celebrating the female representation that brought that scene, which also identified me: a woman possessing her sexuality and sensuality, free to show her. It never did. Because hypersexualization, even if it is done consciously, has not served me anything, the truth. It may be that in some things and sometimes yes, but today I can say that it is absolutely anecdotal, that it is not enough. Moreover, I believe that poverty is fetishized and exotized. And in this particular case, feminized poverty. Not forgetting the cult of social progress. In any case, I feel that these sages and images and universes are not revolutionary, but speak, however, of my class, its contradiction and its division. Unfortunately, the proletariat is not yet constituted as a revolutionary subject, although it is and should be.

How does this all relate to feminism? The

2018 feminism, which brought mass demonstrations and concentrations, which filled the streets, no longer exists. It lasted little. Why? That is the question. I don't know anything, I'm just an actor writing poems and plays. But the characteristic of feminism is interclassism: it promotes friendship among classes. And that detail, which we often forget, allows institutions and companies to assimilate feminism. I still wonder what the working women and the bourgeois women were doing in the same demonstration. At that time he was a geek who read a lot about “class feminism,” although he did not fully understand what it was and still did not. I understand, however, that sickness is capitalism, and that machismo is one of its many symptoms. Capitalism itself generates and perpetuates gender subordination in general and male violence in the forms and forms we know today. And the bourgeois state only offers working women one thing: prevention mechanisms and palliative mechanisms, which have nothing to do with eradicating the problem, with the elimination of machismo.

I like to say that I'm up to the penis of feminism, really.

Recently, in an interview, you criticized the caricaturization that has been done around your figure.

If I had been another eccentric and contingent master, the mediatization of my person would not have been the same. The thing is, I'm not a master, I'm not an eccentric, I'm not even a accountant; I'm a communist. And I'm willing to take its consequences to the end. Because I had no political organization, I thought I could do politics through my public statements: go on television, go on radio, give interviews, etc. But it's not true. It was a crucified road. To speak politically, individually, in the media of the bourgeoisie, is useless; it is sterile. And a suicide. It only serves to caricaturize you and to take advantage of them. If artists really want to make “class” politics – and most say so – their moments, intentions, dreams, etc. But they must be subjected to something bigger and more worthy of being honored. And there is nothing greater or more worthy than a revolutionary organization fighting for the political independence of the proletariat.

It is in the interests of Catalan culture to have dreadful enfant from time to time. But I am not and will not be part of the “artists on the left” quota. By no means. I don't want to be a writer who writes against the bourgeoisie, but who has no problem with the bourgeoisie; I don't want to be a writer who writes for his class, but I don't want to fight for his class. It seems to me hypocritical and false, it upsets me. However, I do not judge it, sometimes I am too moralistic. But to me, to tell the truth, that attitude upsets me, and I couldn't sleep peacefully at night.

.jpg)

And as a writer, how do you stand before this situation?

Nor do I want to be 50 years old and “anti-system”, if that means something today. It's not serious. The label “antisystem” is abstract and very caricaturizing. In the early years, I was caricaturized and maybe encouraged. But you grow, you learn. It is radicalised, as I said before. I want to promote agitation and propaganda, because I believe that these are the main functions of every communist artist; useful and beautiful. And the truth is, I've always been that: good agitator and good propagandist. The only thing that interests me and has always interested me is politics, but I do not think that artists, in this case, can be interested in anything else. Capitalism is the worst enemy of art and literature.

What is the relationship between politics and aesthetics in your literary and artistic work?

My artistic work is based entirely on the dialectic between politics and aesthetics; on the dialectic between ideology and beauty. That obviously has to do with what I am. Throughout my life, I've felt, sometimes, divided between politics and aesthetics. Politics – misunderstood – led me to stop thinking about the right of the working class to beauty, while aesthetics – also misunderstood – led me to a certain bourgeoisie. But theorizing about politics and aesthetics from a socialist or communist point of view is not an individual workshop, nor should it be developed solely by artists or intellectuals. For the moment I can share some intuitions and notions in a simple way, but the best way to contribute for the moment is my work.

For example?

Right now I am focused on the revolutionary potentialities and capabilities – agitators and propagandists – of beauty, both in socialist realism and in socialist fiction. The Communists must know that the struggle of the imagination must be carried out by ourselves. Before we want anything, we have to represent it. And if at the moment our priority is not only to consider the revolution possible, but to wish it, first of all you have to imagine it. And for that, art and literature, both in realism and in fiction, can be useful in creating geniuses and personalisms instead of serving them alone -- I think that's ridiculous.

The gargoyle is not clearly communist. But it's in dialogue with Marxism. And speaking with Marxism as a tradition, as a great story, showed the importance, legitimization and actuality of Marxism.

Next week you come to Euskal Herria to present Girgileria. From 19 to 22 you will be in Pamplona, Vitoria, Bilbao and San Sebastian.

Now that almost five years have passed since the first publication, I come back to Girgileria. I'm happy. Above all I am very curious to know how the book has been read in Euskal Herria, I want to talk to the people there about the work and that they do not take very much into account my love and steta aspect.

Finally, Abolish the Family. A manifesto for care and liberation I want to mention part of the book; it's that of Marxist theorist Sophie Lewis. “In her autobiography, [Alexandra Kollontai] regrets not having devoted most of her female life to [revolutionary] work, but to senseless and cursed love. In Kollontai's perspective, productive work and not care work should be the mission of women's lives. For Kollontai, socializing care is a sine qua non for socialism, because for him work, and not care, make history.”

Bidea da helmuga

Kokein

Balaunka, 2024

--------------------------------------------------

Eibarko rock talde beterano hau familia oso desberdinetako lagunek osatu zuten aspaldi eta ia fisurarik gabe hamarkadatan eutsi dio. Izan ditu atsedenak, gorputzak hala eskatu... [+]

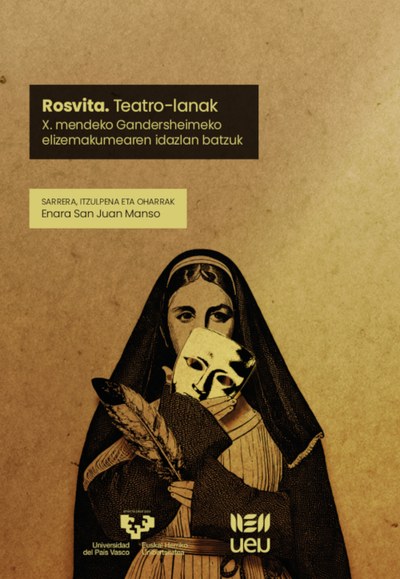

Rosvita. Teatro-lanak

Enara San Juan Manso

UEU / EHU, 2024

Enara San Juanek UEUrekin latinetik euskarara ekarri ditu X. mendeko moja alemana zen Rosvitaren teatro-lanak. Gandersheimeko abadian bizi zen idazlea zen... [+]

Festa egiteko musika eta kontzertu eskaintza ez ezik, erakusketak, hitzaldiak, zine eta antzerki ikuskizunak eta zientoka ekintza kultural antolatu dituzte eragile ugarik Martxoaren 8aren bueltarako. Artikulu honetan, bilduma moduan, zokorrak gisa miatuko ditugu Euskal Herriko... [+]

"Entseatzen gira arnas gune bat sortzen Donibane Lohizunen, hain turistikoa den herri honetan". 250 kiderekin Donibane Lohizuneko Begiraleak kultur elkarteak 90 urte bete ditu aurten. Lau emaztek sortu zuten talde hauetan eramaile izan zen Madeleine de Jauregiberri... [+]

Elgarrekin izena du Duplak egin duen aurtengo abestiak eta Senpereko lakuan grabatu zuten bideoklipa. Dantzari, guraso zein umeen artean azaldu ziren Pantxoa eta Peio ere. Bideoklipa laugarrengo saiakeran egin zen.

Pantailak Euskarazek eta Hizkuntz Eskubideen Behatokiak aurkeztu dituzte datu "kezkagarriak". Euskaraz eskaini diren estreinaldi kopurua ez dela %1,6ra iritsi ondorioztatu dute. Erakunde publikoei eskatu diete "herritar guztien hizkuntza eskubideak" zinemetan ere... [+]

Duela 150 urte, 1875eko martxoaren 7an jaio zen Maurice Ravel musikagile eta konpositorea, Ziburun. Mundu mailan ospetsu dira haren lanak, bereziki Boleroa. Sarri aipatzen da Parisen bizi izan zela, kontserbatorioan ikasi zuela aro berri bateko irakasleekin, munduko txoko... [+]

Desgaitasun fisikoa duen arkitekto baten alabaren etxea bisitatu ondoren idazten dut honako hau.

Desgaitasun fisikoa duten pertsonen taldeek ez dute arkitektoa maite, beraien bizitza zailtzen duen gaizkile bat kontsideratzen baitute. Gorrotoa ulerkorra da: arkitektoaren lanak... [+]

ERREALITATEAREN HARRIBITXIAK

Nork: Josu Iriarte, Nerea Lizarralde, Jare Torralba eta Amets Larralde. Mikel Martinezek zuzenduta eta Jokin Oregiren testuetatik abiatuta.

Noiz: otsailaren 21ean.

Non: Bilboko 7katu... [+]

Elkarteak ekainaren 27, 28 eta 29an Arberatzen (Nafarroa Beherea) izango den jaialdian izateko aurresalmenta abiatu du ostegunean. Hiru eguneko sarrerak 43 euro balioko ditu eta Ipar Euskal Herriko "lau ertzetatik" festibalera hurbiltzeko autobusak antolatuko dituztela... [+]