Basque slavery in the colonial metropolis

- On 12 October 1492 not only did the genocide of the indigenous peoples of America begin. It also paved the way for the business of Atlantic slavery, which would make Europe a global power. This gigantic colonial system would have been impossible without a metropolis like Cadiz: Christopher Columbus and many other conquerors departed from European expeditions, being also the European centre of slave trade. And the Basques played a special role in this.

During these weeks we have seen in Cadiz giant ephemeral dolls of Phoenician gods in Puerta de Tierra, in the Plaza de San Antonio and in other places to claim that the city is “proud” of its past. Ancient Gadir, later Gades, today Cadiz, has also witnessed more distant fragments in history. For example, will you remember that Christopher Columbus organized several expeditions from Cadiz to America after his famous 1492 trip, in order to squander his people and their resources?

Many times, when we talk about the genocide of the indigenous peoples of America, we put the magnifying glass of history in that part of the Atlantic. On October 12, we are full of words to denounce Columbus Day, but we continue to speak with a dehumanizing look at “the other”, the otherness that make up the indigenous and black people. There is no anti-racist struggle if the colonialist and slave past is not questioned, say the friends of the collective Counterpoint Dekolonial of Vitoria-Gasteiz. To do this, we are forced to move some meridian magnifying glass and place it in the metropolis.

The drunkenness of the colonialist past in Cadiz began in 1717. That year the Crown of Castile decided to transfer the House of Hiring of the Indies to this city from Seville. With the impulse of this institution founded in the sixteenth century by the Catholic Monarchs to secure the monopoly of the American expolio, Cadiz became one of the main citadelas of Europe, a megalopolis cultivated in the sea and that gathered tens of thousands of inhabitants. But this vastness had a small trap: one in six people was a slave.

The city of 10,000 slaves

According to estimates by history professor Arturo Morgado, at least 10,000 slaves were “baptized” in the century and a half in Cadiz, bathed in holy water and with a Christian name that stole not only their body but also their own identity, and 17,000 were sold at auction. Many were Dalmatians and Hungarians who the Ottomans had led through the Mediterranean, but above all Africans liked the elites of the city as craftsmen and servants for them.

Morgado draws inspiration from the documents selling historical archives and from the birth, marriage and baptism records of parishes. And it's curious, because the historian also gives another piece of data that destroys the masculinized image that has come to us from the slaves: 52 percent of those sold were women. Yes, slavery has so far been an androcentric story.

But what did we come to tell? Because the city at the other end of the Iberian Peninsula has a special connection with the Basques. Just as today we go a multitude of tourists to search for the sun and the salt, a few centuries ago many good quality Basques arrived there, called by the sound of the chin. In Seville in the 16th century it was enriched with the American colonial trade – and with slavery – as the Basques abounded, in Cadiz there was also a strong community: in which we will find collaterals, chapels and cofradías of the Passion of Christ behind his steps.

Garaycoechea, slave vs. corsario

In the 17th and 18th centuries we found the Basques in the city, be they fleet captains, owners of the surveillance towers that transformed the skyline... and, of course, among the slaves. In the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Cádiz there are numerous documents that demonstrate the involvement of families of Basque origin in this trafficking of human beings.

In 1767, for example, Tomasa Irisarri, a widow of the captain of the ships José Aguirre and Larraguchia, sold his brother Santiago Irisarri a “black slave” named José Benizo in exchange for 100 silver ducts. A year earlier, Ignacio Zurbituaga had ordered “liberating” a 26-year-old slave, María Dolores, to marry another “free” slave. The former slave boyfriend was called Caietano Mendieta, and the document states that he was “owned by Pedro Mendieta.”

They are often found in notarial protocols and wills, as, in addition to the artificial name, slaves carried a beautiful signature from their owners for their entire lives. This is the case of Miguel Leaburu. We do not know whether the Portuguese kidnapped on some African shore or were born in Cadiz and bought it by a rich leaburu, but we know that in 1759 he achieved freedom.

Miguel Garaycoechea also achieved freedom in 1761 by the will of his superior, Pedro Garaycoechea. The latter's family was originally from Lesaka and Peter made a fortune as a corsary by capturing Dutch boats. A well-known pasadizo under his elegant house, in the center of Cadiz, is still called like this: “The Arc of Garaicoechea”.

Black Company: first slave company

Copied to Portuguese and English, the Spanish crown wanted to turn slavery into a big business in the mid-eighteenth century. He needed fuel, labor, human flesh for sugar plantations that flourished in his colonies, and, directly or “right,” he started giving permits to go to the African coast. The Basques were also the main protagonists.

In this context, in 1765 they founded in Cadiz the first company in the world specialized in the purchase and sale of slaves and gave it a name of dreadful: Company Gaditana de Negros (Compañía Negra de Cádiz). Among the major investors (Miguel Uriarte, Juan José Goicoa, Francisco Agirre, Lorenzo Ariztegui..) are the most complicated Basque negotiators in the dark traffic, who left a macabre legacy: By the time it was liquidated in 1779, it had already transported over 27,000 slaves across the Atlantic.

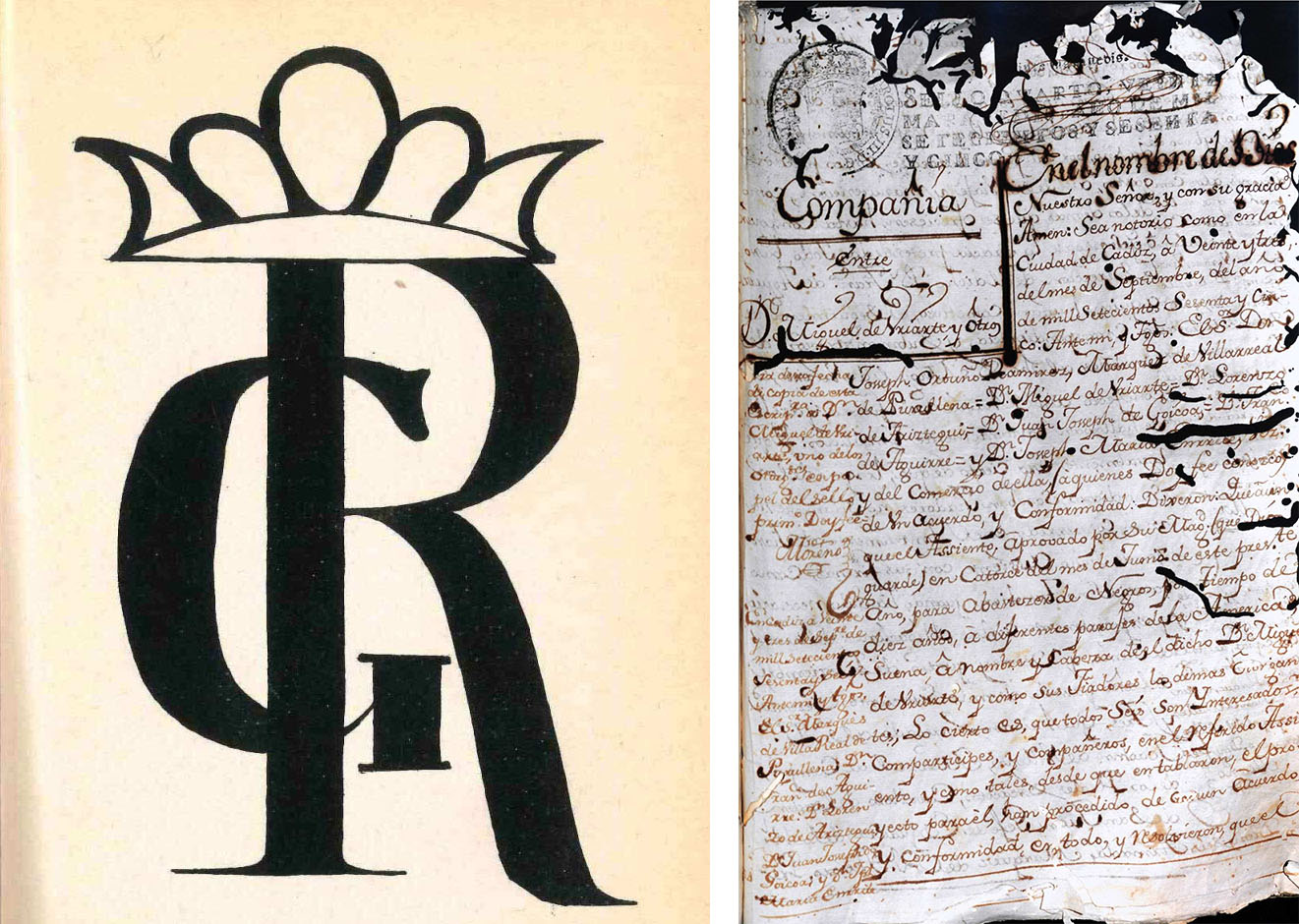

This story has been erased with a tipex for two centuries, until in the 1970s the Andalusian researcher Bibiano Torres picked it up in a book: “It’s very difficult to take stock of what the company has achieved with this black trade,” he said with rage at the beginning. Today we know something more about the company, and the Provincial Historical Archive of Cádiz shows as a treasure the founding document of the Basque slave company.

Black Company Fingerprints

In the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Cádiz, in the notarial protocol with number 4.502, the foundational document of the Compañía de Negros de Cádiz is preserved (above, in the image of the right, written in 1765. Officially it was called Aguirre, Aristegui and Cía, which represented the hegemonic presence of the Basques in this business.

Among other conditions, it is said that the company would not accept women who had just given birth or those who had “fallen breasts”. Nor would he accept the “impaired” blacks, such as the “blind, sick or sick, and those who have the navels out because they are screwed.” They didn’t want the Buddha because they “have teeth like a saw,” but they did want the cabarali. Musangaes, mondongos and angolias no, but yes lukumias, mines, mandings and mososos...

Yes, all of them were marked with the symbol of the company in red carinbo (above, in the image on the left), in which they made no distinction.

Mendinueta, the well-known Basque trafficker in Cadiz

But we know much less about another trade network created to bring slaves to South America. Navarro Francisco Mendinueta, based in Cadiz, obtained in 1754 a seat or authorization from the Crown of Spain: for ten years he could charter six boats towards the Río de la Plata, loaded with a large quantity of goods, and among them 3,000 black. By 1760, all the boats had already made this journey, some directly, and others passed through the Gulf of Guinea in search of the precious “merchandise”. However, the departure of San Ignacio occurred later, as he was still in the port of Passages carenizing. This boat was handed over by the powerful Uztariz family to Mendinueta, but we do not know if the skipper eventually achieved his goal.

As can be seen from the legacies preserved in the Archivo General de las Indias in Seville, Mendinueta complained that he was not profitable for human sale, among other things because he did not wear clothes for the slaves that were piled in Buenos Aires and because “how they sleep outdoors they die”. It quantified, of course, the loss in money.

At that time the slave trade was legal and many others wanted to make money selling human bodies. For example, Julián Antonio Urkullu de Las Encartación and Julián Martínez de Murgia de Gorbeialdea made requests for the transportation of black slaves in 1770 and 1773 respectively. But the difficulties of the Cadiz slave lobby put their pretensions on the top.

The Last Blackboard in Europe

Starting in 1817, when slavery was formally outlawed in Spain as a result of an agreement with England, a new era of gold began for the traffickers: the black market. Slave trips to the secret colonies became much more profitable because of the risk of being captured by the English army and Cadiz was one of the favorite ports of smugglers.

In 1864, the British Consul in Spain, Alexander Dunlope, acknowledged in a letter to the UK Foreign Office, Foreign Office, that Cadiz was at that time the “European slave trade centre”. And it looks like this.

The historian Lizbeth Johanna Chaviano of the Pompeu Fabra University has compared the sources of the Foreign Office with those found in the imposing Internet database Slave Voyages to show the extent to which the merchants of Cadiz are stained by the mud. 65% of the slave ships of the Iberian Peninsula, at the time when slave trade was illegal, sailed from the port of Cadiz, with 51 shipments in total.

Until very late, slavery remained in Cadiz, to such an extent that it was the port of the last in Europe to practice this genocidal transport, specifically until 1866. While in most cities this traffic was a thing of the past, in 1863 Consul Dulonp, surprised, had still seen several steam boats on the docks of Cadiz preparing to travel to Africa. Among them was the Cicero, sent by the great Alavese slave Julian Zulueta. On 5 November they appeared on the mythical beach Girón (Cuba) with 960 people in captivity, while another 149 died during the journey.

According to Chaviano, Cadiz was for a long time the center of the “commercial houses” that were involved in the slave trade to the noses, a trampoline to open doors of other ports and businesses. Let us not say anything for the Basque fortunes that arise from there. And while for some it's an uncomfortable thing about the past, it needs to be remembered so it doesn't become such an ephemeral story as Phoenician dolls.

.jpg)

Cádizko hiriaren galtzada-harrizko kaleetan barrena ikusmiran den turistak oraindik suma dezake eraikinen eite airos bat eta halako atmosfera kolonial bat: La Habana es Cádiz con más negritos, Cádiz La Habana con más salero... dio habanera famatuak. Kubako hiriburuarekin sinbiosi hori XIX. mendean bereganatu zuen, azukre eta esklaboen abaroan aberasturiko merkatarien jauregiekin bete zirelako zabalgune berriak (1).

Mina plaza zen eliteen bilgune nagusietakoa, bere drago eta palmondoekin. Eta hantxe eraikiarazi zuen José Matía Calvo (2) laudioarrak beretzako etxe bat 1840ko hamarkadan, orain arkitektoen elkargoaren egoitza dena. Matíak txinatar esklaboekin trafikatzen egin zuen bere fortunaren zati bat eta, besteak beste, Cádizko Bankuko fundatzaileetako bat ere izan zen. Bizitzaren amaieran, itxuraz atake filantropiko batek erasanda, bere diruak zaharrentzako egoitzak egiteko utzi zituen Donostian –egungo Matia fundazioa– zein Cádizen.

Beste esklabista askoren lorratza ere jarrai daiteke Cádiz zaharrean: Compañía Trasatlánticaren bulegoak (3) Antonio Lpez kalean zeuden; Sierra Leonan esklaboentzako biltegi bat izatera iritsi ziren José eta Fernando Abarzuza anaien konpainiaren egoitza eta jauregiak nonahi daude; eta Pedro Felipe del Campo Labarrieta (4) gordexolar agente negreroa-ren etxea katedraletik bi pausotara.

Portura arrimaturik, berriz, Arabako Zulueta klanaren etxe horixka (5) bat topatuko dugu antzinako gerra-kanoi bitxiez inguraturik. Pedro Juan Zulueta bizi izan zen bertan, Cádizen bezala Londresen zituen banku-negozioekin esklabo trafikatzaileen kapitalak kudeatzen abila, besteren artean Kubara 800.000 esklabo eraman omen zituen Agustín Sánchez Ríansareseko dukearen –Maria Cristina Borboikoaren senarra– diruak maneiatzen zituen.

“In the newsletter today at noon, you will see the mayor of your capital, offering the main plaza of the city to the military body that tortured us. In today’s information at noon, you will see the structure that murdered our friends and relatives unravel through our... [+]

A few years ago I spent a weekend in Pamplona. It was October 12.

I was surprised to see dozens of Latin Americans celebrating ephemerides, with concerts, txosnas and everything. Had I celebrated the conquest of my ancestors? ! I thought that the cultural assimilation of the... [+]

On 12 October the beginning of the genocide of the indigenous peoples of America is celebrated, and in ARGIA we do not join the ideas behind that feast, because they do not represent our values. So today, Thursday, we're working. Lasarte-Oria’s headquarters are open and the web... [+]