Sexual assaults in childhood mark the whole of society

- Media reports on several occasions that the coach has sexually abused a child in a locality of this kind. On other occasions, it is heard that a child's grandfather has been arrested on charges of sexually abusing his granddaughter. Less frequent is that the one who assaulted the child is the father. This arouses alarm and fear. In these cases, the response of society is usually surprising and rejecting: How is it possible that in our “developed society” we want to have “sexual relations” with a child? It is impossible to understand. Convinced that he is “crazy” and that these “barbarities” are only made by the priests who have the support of the Catholic Church, the most comfortable thing is to look away, because it is too hard to digest. However, this report highlights that they are a structural problem and that, therefore, the whole of society is responsible for their avoidance.

The philosopher and writer Susanna Minguell (Barcelona, 1983) warns us of the danger of a moral vision of sexual assaults in childhood: “We need to look from a point of view that marks the distance, to think that my daughter cannot pass this. But the only thing we're saying is that sexual violence in childhood isn't something everyday, and that's not true." Dislocated Words (Editorial Descontrol, 2019) gathers the experiences and learning he has had in the process of the formation of sexual abuse he suffered in his childhood: “You start asking questions: what has happened to you, what happens for it to be socially authorized…”. It clearly states that it is not only something that has happened to him, but that it is a political issue and that it needs a structural reading. In this sense, he has organized several workshops and recitals in Euskal Herria in recent years, aimed both at people who have suffered sexual assaults and professionals who work with children.

“When you politicize, create a network of protection in your environment. Looking from a political point of view has a cathartic point, because you also see yourself as a political subject. I am not Susanna Minguell, a person who has been abused, who has no remedy. The abuses I have suffered are not the center of my life, and there are more people who have passed on to him.” If treated as isolated cases, Minguell’s message is that you can never worry about the problem, “and I still think yes, you can deal with this public health problem.” However, he knows that it can be “a matter of generations” to turn the situation around.

In fact, far from being isolated cases, the data reveal a harsh reality: between 10 and 20 per cent of the population has suffered sexual assaults in childhood, according to the non-governmental organization Save The Children. Eyes that don't want to see. The Annex report on the Basque Country analyzed the statistics in detail and concluded that one in five girls and one in seven boys have suffered sexual assaults in childhood in one way or another. According to this study, abuse occurs when children are between 11 and 12 years of age, and the aggressor is usually a well-known street authority. Girls, on the other hand, suffer them at the age of 7 to 9, and the aggressor is usually from a close family.

This data is known by social educator Asier Gutiérrez (Hernani, 1987), who has taught, among others, two courses from the UEU 2022 and 2023 and has taught several courses on violence against children and adolescents. Compared to the rest of the violence, she has pointed out that sexual violence is "very complicated". “To begin with, we must all understand that sexual abuse is something that emerges from power relations,” he said. Minguell has also insisted that there should be a focus on understanding sexual abuse in childhood, on the power that adults have over children: “The aggressors are normal people. What happens is that they care a slut that person in front of them and that they want to exercise power over that child. And that power is exercised in a sexual context, that’s it.”

In this situation of inequality of power, a voluntary, communicated and appropriate agreement is not possible (i.e. without violence or manipulation, knowing the consequences of the action and with the ability to choose other alternatives). The Basque Strategy for the Fight against Child and Adolescent Violence 2022-2025 recalls this. Minguell’s reading is that “childhood is stolen”, in the hands of adults: “We tell the children how to reason among them, what clothing to wear, how to speak, to whom to give two kisses…” He criticizes that adults have also robbed children's bodies and that they are not taught to own their bodies. He considers that this dependence that has been internalized since childhood also influences the aggressions: “It’s very possible that a child doesn’t say no to an adult. Because an adult always has status, social and physical, and that's what children know, even if it's unconsciously. How can I say no to my uncle? Or this person who measures my triple? How can I say no to this 45-year-old, I'm a kid? In addition, you have to take into account the fear and panic you may have.”

One in two sexual assaults takes place in the family

In the case of Álava, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, it is estimated that only 2% of sexual assaults in childhood are known at the time when “complaints have a lot of resistance related to taboo and stigmatization”, according to the report. This means that many other sexual abuses are unknown and therefore continue over time; they are not one-off attacks, because they have the possibility of keeping them hidden and unpunished.

The report of the Euskadi Strategy also provides data that belies many myths, such as that sexual assaults occur in all types of families, even in the upper class. Another misconception is that the abuser of the child is unknown, while some 2020 records have shown that one in two cases of sexual assaults occurs in the family environment of the child or adolescent (friends, large family members, reference persons...). In particular, 80.8% belong to the environment of trust and one in two to the family. As in cases of male violence, almost all the aggressors are men (95.8%). Outside the family, 14.8% of sexual assaults occurred in other homes and 12.3% in school or in after-school activities, according to data from the Basque Strategy 2022-2025 report.

The family, which should in fact be the refuge of the child, becomes for all of them a space of violence. “The problem is the family and all the repetitions of that structure,” Minguell said. “The family is a hierarchical institution in which the figure of the father, the figure of the pater is found; it marks some directives and the rest must follow them. If the patriarch decides to abuse his daughter or son, he must be followed.” Susanna Minguell has warned that the family is the institution that allows sexual assaults, “this tremendously classical, totally heterosexual family structure.” He also says that the family structure is maintained by silence, “and the child knows that, although unconsciously, if he says something, everything will be unbalanced.”

Asier Gutiérrez has also referred to the relationship of power in the family, and the loyalty of children to their parents. “The child until the age of 7 is not able to say what is OK, what is OK... everything his parents do to him is normal. They start to differentiate in school, to have another perspective, to realize what is right, what is wrong, what they like, what they don’t...” She recalled that this first stage is especially vulnerable, and that at 12-13 years they are the origin of many mental health problems that emerge during adolescence. “I also reflected, as a father, because I see the relationship that the child has with me, and I have clearly seen that power. For children, parents are gods. From this position all the caveats that come to you can happen.” Gutiérrez insists that the family is the most important refuge, but at the same time, the space that can cause the most pain, because it is a private space, both the nuclear family and the large family. As a social educator, her experience has taught her that sexual violence is the most difficult to intervene compared to other violence: “Sexual abuse occurs in the private sphere, the smallest core of privacy. Getting in there is very difficult.”

Why do you look the other way?

Being the data so raw and high, why is there so little talk about sexual violence in childhood and adolescence? Minguell and Gutiérrez claim that the taboo is gradually breaking, but that silence is total. “Bad said, it’s a shit to assimilate it – Minguell acknowledges – if we admit that the neighbor below sexually abused his daughters, and the other there his students, etc... Accepting that is a blow to the social structure.” In his opinion, society is at a "frivolous" moment in which it can recognize a problem, as long as it does not point to oneself. “But childhood sexual abuse tells us at all times, if you know that the neighbor abuses his daughters, for example, you can’t shut up. But if you denounce it, then you don’t know what to do, it’s too hard...”

Minguell believes that it's hard for people to become aware, recognize that there are sexual assaults in childhood, and be aware that they can also be suffered by their children. This does not help to break the taboo either. “There is a part of society that does, that is conscious, but in that the risk is that it should be added on the opposite path, that is, to educate children in an intolerable fear, trying that nobody touches it, but then they can suffer abuse.” It says that the balance must be sought between the two sides: to be aware but without awakening alarmism.

In Gutiérrez’s words, because sexual assaults on children are “very crude”, some “don’t want to know anything”: “The reality is that there may be many children – or that we are, I also enter – who have not noticed that they have suffered sexual abuse, but in a moment, when they get into bed, when bathing... it can happen. Tobacco is also why, if sex is taboo, imagine if we put sexual abuse and children in the middle, tobacco multiplies.”

In any case, Gutiérrez believes that there has been a shift towards the positive on the issue, especially because prevention is given increasing importance. He has worked for ten years in social services, until 2022, and has been a close acquaintance with cases of childhood violence. Gutiérrez believes that it is easier to talk about the topic than when it started and believes that in younger generations of professionals working with children and adolescents there is more dedication, more interest in dealing with the topic. Among them, he has pointed out that it was a great boost that in 2021 the Spanish Government approved the Organic Law against the violence suffered by children and adolescents, LOPIVI, which put the case on the table and on everyone’s lips.

Debates of the European Parliament

Agents and institutions have long been calling for a law to protect children and adolescents, and in 2014 the process began in Congress. Seven years later, the implementation of the LOPIVI law in the Spanish State in June 2021 was an important achievement. Since then, the Organic Law for the Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents from Violence recognizes a number of general rights, although its implementation in practice remains more complex.

They wanted to give a comprehensive view to LOPIVI and paid special attention to pedagogy and prevention. The law has been positively assessed in general terms, including Save The Children defined it as a “breakthrough” and insisted that the law has taken up the demands that the institution had been making for years.

However, Save The Children has called for concrete steps to be taken to give effect to the law. First, the NGO criticises that one of the fundamental pillars, such as the specialization of justice, has not yet been established to guarantee the best interests of the child and to prevent revictimization. To this end, they have asked the Government of Spain to develop a specific bill for this specialization. It has also called for other legislative developments to be followed within the framework of LOPIVI. The organization defends the need to allocate the necessary resources to ensure the effective implementation of the new law, and considers it essential to create a Unified Register of Violence that “better collects data” on violence against children. Finally, Save The Children has demanded that all professionals involved in cases of violence against children receive specialized and specialized training.

Gutiérrez taught the basic knowledge of LOPIVI to the professionals who enrolled in the UEU courses, mostly teachers who work with children and adolescents, and this has a similar view: the law has been a step forward, but lack concretion. “It establishes a legal framework that homogenizes all state protocols. Otherwise, it is talked very generally and has no real impact, because there is no talk of money, for example, it is not said that they are going to be allocated a item or that the administrations are obliged to do so”. These generic references to rights are, among others: it includes the need to guarantee child participation, the right to be heard, the duty to have safe spaces...

One of the points highlighted by Gutiérrez is that this law also provides for vicarious violence, that is, the status of victim is recognized to the children of women victims of male violence. Although until now the mother of the child had suffered machista violence from the child's father, man had the right to be with him and that "has no logic", according to Gutiérrez. “Children have the right to be with their father because they have that emotional need. But you have to be very measured and that man has to do a process; today it is not done or it is only done if it is by the father’s own will”. Another problem of patriarchy, he said, is that "boys and girls see themselves as properties." “Children are not ours, they are subjects, they are part of the community and they have their rights.” It considers it important to inform all children that they have these rights.

School Protection Coordinator

The integral character of the Law implies that society as a whole is committed to dealing with the violence of children and adolescents, as well as to respect and fulfil their rights. The welfare of children must be guaranteed in all areas, and the law includes: society, family, criminal and judicial, school, police, sports and leisure areas, health system and internet.

The school requires the commitment of the educational community and, in addition to demanding protocols to act against violence, a new figure has been introduced, that of the coordinator who guarantees well-being and protection. In the sports field, the law obliges professionals to receive training, and in addition to the obligation of protocols, it introduces the figure of the protection delegate. One of the solutions proposed by Save The Children is to provide ongoing training for children to be more protected.

What roles should these two figures play? In schools, the coordinator shall develop training plans on prevention, rapid detection and protection and inform all staff at the centre of the protocols. It will also coordinate cases where the intervention of social services is required and will promote methods for the peaceful resolution of conflicts. The functions of the representative of sports and leisure centres are similar: he will listen to the concerns of children, extend and implement the protocols, and report on this when a case of violence is detected. The idea is that these two profiles are trusted people of boys and girls, so that, whatever happens, they will address them and them to dialogue calmly. Once again, it should be remembered that there are agents who have denounced the lack of means to enforce the law, so it is expected that these figures are not in all educational centers.

By creating safe fields, they emphasize the concept of “being heard.” In these spaces where children feel good, it is essential that they feel heard, especially when something has happened that has made that boy or girl not comfortable. On the other hand, with regard to the right to be heard, the telephone number 116111, i.e. the Zeuk programme, is also under way.

How should teachers act?

The UEU organized the courses after the implementation of the LOPIVI, at the hand of Gutiérrez, and the social educator has clarified that most of the participants were unaware of the protocols and lacked information. If a teacher suspects that a student suffers violence, what steps do they have to take? Contact the reference figure (consultant, counselor) that should be in each center because it is the one that leads cases of children in situations of lack of protection. This person should be directed to the address or reference person of each school. From there, the benefits that the complaint can bring should be valued, as stated by Gutiérrez, and it would be in contact with the social services of the municipality. All these professionals have to work together and then, depending on the seriousness imposed on them, it will be decided from the social services whether the complaint is lodged or is referred to the specialized social service that the foreign ministers have. “Of course, if there’s evidence, if you see a child being beaten, it’s best to report it directly.”

He considers that through courses and lectures the faculty performs “chip change” and prepares for observation and vision change. “The standpoint of normalisation of violence needs to be changed. It is not a question of victimizing, saying ‘sick child’, but of claiming that this child has rights and that I have to partly guarantee those rights.” In the case of teachers, one form of protection would be to be attentive to how the student is doing, how he goes to the patio and how he returns, for example. “Do not simplify, because I have heard many times: ‘The child is very quiet and very closed and has no friends’. And you're done. Well, he may have emotional problems, have you asked him how he's doing? And I don't want to devote all my responsibility to the teachers, I know it's exhausting, but we have to be aware that that problem exists, and that's why I'm going to put all the tools that I have to take care of it."

Gutiérrez has valued the preventive work that teachers can do, as the school is one of the most appropriate screening points. However, it does not believe that responsibility should be assumed. “The education system should have a figure that is incorporated into the classes from Early Childhood Education and has a very busy subject,” he proposed, although he is aware that in the short term this is “impossible” because among other things it requires significant economic investment. The case of Andoain known in social services is a positive example in this sense: two psychologists were in primary school from 3 years onwards and were in charge of working to prevent violence. Until this figure is guaranteed at all ages, he stressed that the ideal would be for teachers to receive minimum training that would allow them to have basic tools and detection guidelines. He argues that the response to violence against children should be “very comprehensive”, which is done in collaboration with the health system, social services and professionals who cover all the needs of the child.

Effects of the complaint

One of the positive developments of the law has been the judicial and criminal field. On the one hand, the margin for prescribing the most serious crimes is widened, and within this group is sexual violence; it is a historic request to increase the prescription. Until now, the report began when the aggressor was 18 years old, and beginning in 2021, it began to count when he was thirty years old. It is proven that the person who has suffered sexual abuse needs time to process what has happened, and in some cases it takes many years until a decision is made to file a complaint.

On the other hand, a step has been taken to prevent the revictimization of the child whistleblowers. In the case of children under 14 years of age, prior evidence will be admitted and it will not be necessary for the aggression to be reported for the umpteenth time before the judge, since in many cases it was in the presence of the aggressor. At LOPIVI they have recognised that the fact that attacks have to be remembered time and time again can cause added pain. It is estimated that the maximum number of counts before the authorities concerned will be three times.

Asier Gutierrez criticizes revictimization and says that although the law more respects this aspect, children are still unprotected at the time of the reporting process. In addition, he recalled that there are some who are retiring: they say they have suffered sexual abuse, but when they see the effect this entails, some are paralysing the process. “It can happen mostly in school, you may tell a teacher, but you see that the teacher does not have the competence to manage it, and there may also be pressure from home. The child returns from school to his/her home, where the aggressor and the person who protects him/her can be, and in that climate the child has to survive.” Gutierrez states that the child can realize that what is out of the house is “worse”, because among other things he will suffer victimization, and the child sees that the denunciation process “makes no sense”; “in some cases they count on sexual abuse but then go back and say otherwise”.

Susanna Minguell has also been critical of victimization, as it “homogenizes” all people who have suffered sexual assaults. “The victim is like a social category. It is taken for granted that all people who have experienced sexual abuse in childhood or adolescence will react in a certain way, we have a certain personality.” He explained that entering this category means that the victim does not have an agency, which limits doing what others say and expect. “The pathology of the victims is very harsh. I'm not sick because I've been sexually abused in my childhood, OK? I've experienced an experience that's been crap, but I'm not sick and it's already." Minguell is aware that this attitude is out of the ordinary and that society is not used to listening to victims who do not speak of weakness, but of anger. He stressed that victims of sexual assaults in childhood have been subjected to a “very savage stigma”, “in which the victim always falls below all others”.

Minguell's attitude is certain: he does not accept being read as a victim. In his opinion, this victim figure shows that the life of this person has been “completely marked” and does not agree: “Of course, sexual abuse marks, but they can be tackled. It doesn’t mean they overrun, I don’t like that word, it seems that we jump over the fences and catch each one of us passing by the back.” He considers it essential to rethink the story about the victims and the stigma.

What happens when silence breaks?

Taboo, silence, shame, guilt; these are words that are repeated when dealing with this issue. Don't tell anyone (Elkar, 2022) is the title that Maddi Ane Txoperena titled to the book that narrates the story of the protagonist Lide. A person close to the family, as a child, sexually abused Lide and, after having the memories abandoned, begins to remember what he has suffered upon his arrival in youth. The title summarizes, among other things, why silence is the predominant one: In today’s society, messages like “Don’t say, hide” are evoked. And in the novel it explains a habitual situation: amnesia. Minguell, in his work Dislocated Words, points out that temporal amnesia is not sufficiently emphasized, nor the issue of retrieving memories of sexual abuse in childhood.

“Those memories of abuse are also an experience in themselves and can put upside down the life of the person who remembers them. You may realize that his life trajectory has been around abuses that were not known, that he might not be aware of what he was living at the time, or that it was psychologically impossible for him to interpret as sexual abuse.” At the moment memories are recovered, “life can lose meaning” or it can be a feeling that “everything has been a mistake”, as it is thought that there are patterns that are repeated both with the partner and with the way of relating to others, for example, and it begins to name those who so far have no name, when it realizes that they can be related to sexual abuse.

Not being a child, not being an adult, it is easy to report what happened with a loud voice. “I will break the silence if I can, if I have a protective net around me.” Susanna Minguell cautiously proclaims the idea of breaking the silence and denouncing it: “I will break the silence, but who will receive me later? Are you prepared to break the silence? Who is silence? There is also frivolity.” Gutiérrez also joins the need for the network and is clear that becoming aware of sexual assaults requires a lot of work: “In therapeutic processes, for example, if you work in trauma, you can’t tell that person that suddenly ‘hey, did you suffer sexual abuse when you were a child?’ and leave it there. When you open such a process, you have to support that person.” It can cause a backward turn, relive what a close person has done, and that creates a “very strong” grief; “it takes a very deep and complicated job,” Gutiérrez insisted.

What happens when a person in your environment informs you of sexual abuse? Are we prepared to manage it? “It unbalances the environment and the person who has suffered the abuses knows it – Minguell acknowledged. I understand that the environment gets really nervous, because they're not robots. If a friend tells you what they've done, you feel like finding the guy who's done that and shattering his face. But if the friend does not want that, it can be, then, first there are the needs of the person who has been abused.” He is aware that in the face of these situations a great emotional burden is assigned to others, and proposes that this help be well thought out, even if external help is required.

Shared spaces beyond therapy

People who report sexual assaults, both judicial and social, are destined to a therapeutic process that, in general, complements what has been experienced. However, Susanna Minguell has the impression that it is necessary to go beyond therapeutics and pathology to create spaces for dialogue between people. He said that the experiences he has had "have borne fruit". Their process began to become popular in 2018, through recitals, exhibitions, workshops, etc., and year after year people have ratified the need to speak of the issue from another point of view.

The first workshop was organized in Tolosa, in 2021, with the collaboration of the Tolosa Equality Area. He says there were attempts that he will never forget and recognizes that he was particularly surprised by the need for people to meet in those safe areas of trust. According to Arriola, there were many participants in the initiative children who suffered or were close to them, who built moments of intimacy and a sense of security. “People need to talk, but also listen, especially to know other perspectives and stories.” He also saw in the workshops that the professionals had the need to speak, “and that’s very nice.” Minguell, in his sessions, tries to complete stories beyond the strictly testimonies and give a more social view to sexual assaults in childhood, broader, which can also question one’s own story or point of view and recognizes that it is “risky” to encourage participation.

Along with Minguell, the works of Maialen Sarasola, Cristina Hernández, Miren Atxaga and Maddi Ane Txoperena were exhibited in the topic of Tolosa, with the objective of publicizing the work of sexual assaults in childhood. He has since given lectures and workshops in different locations in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia for a couple of years. Although in the last year he has had to stop everything because of his mother's death, he announces that he is organizing something by October 2024.

Can we protect children from sexual assault?

All those who have worked or experienced the subject speak of the importance of prevention, but the reality is that there are no magic formulas to avoid this type of violence that sustains the heteropatriarchal system. “As long as there are power relations in our society, there will be violence and children will also have to endure it,” says Gutiérrez. “Can we prevent sexual abuse? I don't think so. Can we prevent us from sexually abusing? Yeah, that's it. This remains within us and requires a very structural reflection on our behaviors and relationships with parents”. He says that of all the violence generated by the system, children and adolescents cannot be protected, and what is more, he advocates that children also become conscious. “They have to work that autonomy and know that there is also a society outside the family where there is violence and they have to have tools to avoid it or at least to protect themselves.”

Minguell is of the same opinion, to give children the existence of this problem. This does not mean that they are responsible for not causing sexual assaults: “We do not have to do anything for underage people to say no to the aggressors, but at least what we have to do is not to get into a situation of dissociation, because they cannot stand by and understand what is happening to them. I dare not say that sexual abuse is less painful than if it were dissociated than conscious. What happens is that we should make that person aware or at least know how to ask for help.” To ask for help, according to Gutiérrez, it is necessary to explain to minors that there are spaces in which they can tell how they feel and in which there will be people of trust. It has to be shown to them that emotions have to come out and that they have the right to be well.

If the child is able to express what is happening, Minguell says that the first step is to “stop scanning.” She considers it important to listen to the child from the horizontality, to listen well to the words and what the body says. And he has called for respect for the rhythm of those who have suffered the aggression, since some of them do not want to denounce it at the time, for example. “Don’t enter the logics of power, saying how they should feel, what they should do… all those logics are made to help, but the other takes power away from themselves.”

Minguell has insisted that action be taken in the same way when the narrator of the sexual assaults suffered when he was a child is an adult. Repeat the idea of not victimizing: “Sometimes I have found that look of grief, which is very hierarchical and which tramples you down. First, it tells you, albeit involuntarily, that you're less, and then it tells you that what you've lived isn't experienced by everyone, and it's not. Therefore, be careful with your gaze.” The ideal is the role of listening and accompaniment: “Let that person know that you’ll be there, but don’t say what they have to do. Imagine that you've been told that a friend has been sexually abused, and then you have a time when you resort to hypersexualization; for you to be by your side, to be with you."

The data is not encouraging, and instead of ignoring them, Susanna Minguell and Asier Gutierrez ask for awareness and responsibility for the case of sexual assaults. In fact, the wolf that in children’s stories is depicted as “a dangerous stranger” is almost always someone close. The two interviewees do not believe that the problem will be solved easily, but value the steps being taken in society. They have made it clear that the guarantee of the rights to “stolen children” belongs to everyone.

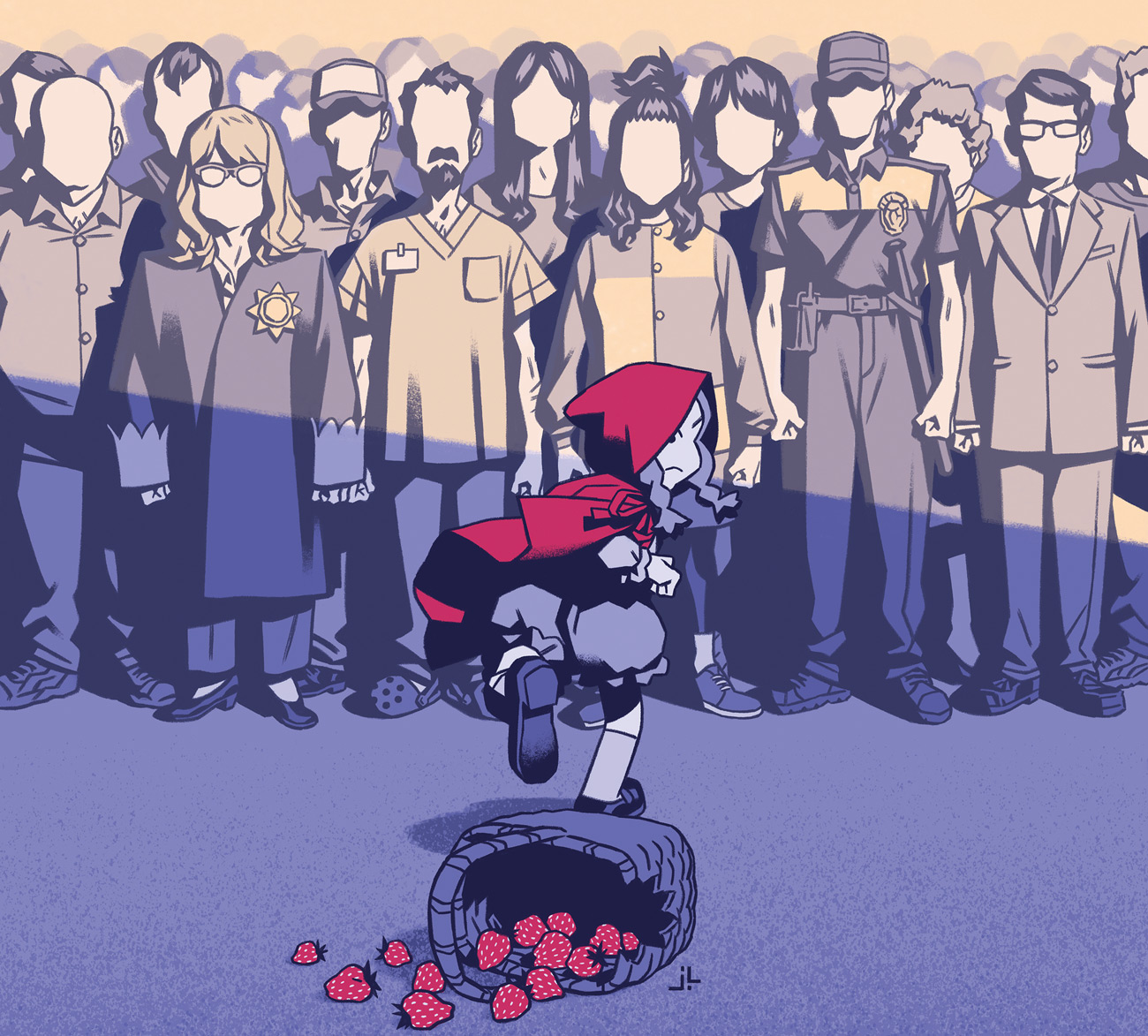

Communicating through stories

The anthropologist Laia Pibernat i Mir, the social educator Alba Barbé i Serra and the illustrator Judit Piella have created the illustrated tale The Biking of Lola (Edicions Belkind, 2023) to explain in a pedagogical and understandable way such complex issues for boys and girls. The authors assert that it is a “unique opportunity” to learn and know the emotions of the characters and that it serves to develop and enrich the emotional and affective vocabulary. The protagonist Lola is a victim of sexual abuse by his uncle, but without being so explicit, this is expressed through different elements and characters in a story full of colorful illustrations. For example, if the moment of sexual abuse is difficult to explain, Lola's bicycle can be used as a means, as they also use it as a symbol in the story. The authors wanted to do a pedagogical work and with the publication of the book – original in Catalan and translated into Basque and Spanish below – they gave lectures. In October 2023 they visited several localities in the Basque Country. Now they're making a short film.

To make it easier to read, many information has been posted on the website: “Adapt the language to the children you’re reading the story and tell them things by name. Express messages clearly and simply to understand the right to one's own body to know situations of well-being and discomfort. These messages will serve to learn about any type of violence and, especially, communication strategies for the prevention of sexual violence. The objective of the authors is for the child and the adult to speak naturally on the subject, so that, in case it occurs, the child has tools to tell it.

The whole story is focused on it: from the children's gaze, from adventure, suggests behavior in case of sexual assault, and all characters have their role or place. They propose clear messages with the child to talk about the theme:

- Your body and everything you do with it is part of an experience where you can participate, decide and choose.

- In this experience you can always negotiate.

- In the body there are intimate parts (vulva, penis...) that an adult person cannot touch.

- Only the people we care for can touch it when we help you wash it or when you do something you can't do just as a child.

- No adult can ask you to touch your vulva or penis.

- It is important not to keep any secrets about your body or the games you make with it (for example, the secret caresses you do with other people! ).

- If an adult person bothers you or makes you feel afraid, it is important that you communicate it to another adult person.

- It's important you don't do anything you don't want with other kids.

"You can ask me anything you want!"

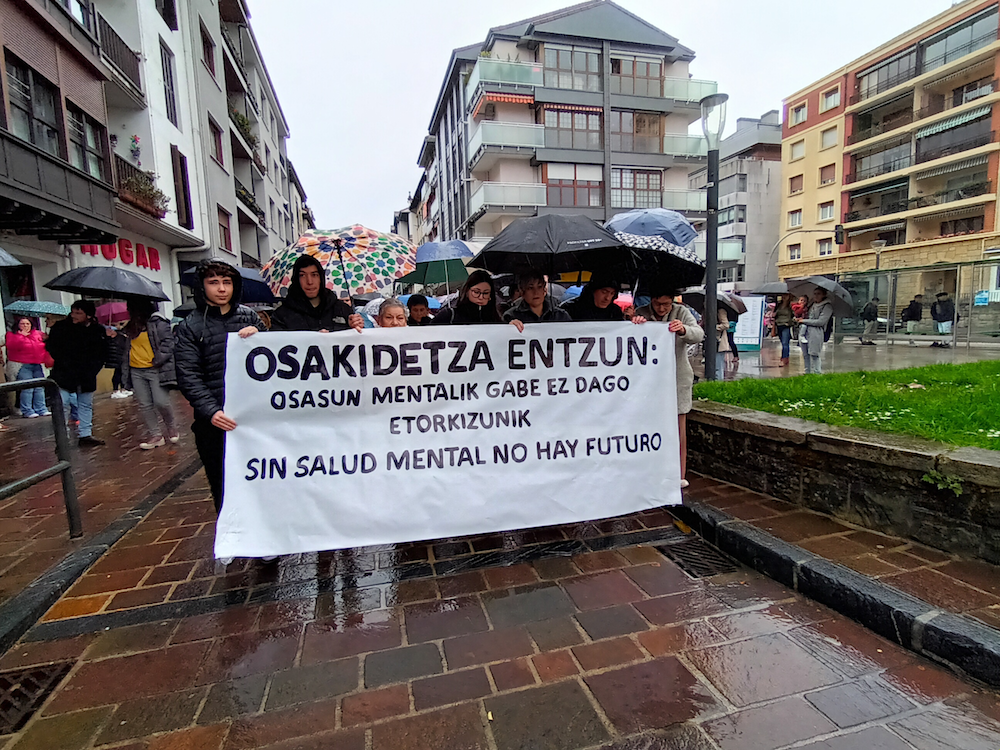

Psikiatria zerbitzua Bidasoatik Donostiako ospitalera lekualdatu dute. Hori salatzeko, 'Osakidetza entzun: osasun mentalik gabe ez dago etorkizunik' lemapean manifestazioa egin dute 12:00etan.

We learned this week that the Court of Getxo has closed the case of 4-year-old children from the Europa School. This leads us to ask: are the judicial, police, etc. authorities prepared to respond to the children’s requests? Are our children really protected when they are... [+]

Today, the voices of women and children remain within a culture that delegitimizes their voices, silencing their experiences, within a system aimed at minimizing or ignoring their basic rights and needs. A media example of this problem is the case of Juana Rivas, but her story... [+]

With the words of poet Vicent Andrés Estellés, I am one among so many cases, and not an isolated, rare or extraordinary case. Unfortunately, no. Among so many, one. In particular, according to the Council of Europe, and among other major institutions such as Save The Children,... [+]