"We still have the traumas and symptoms of the war of our elders."

- Their parents were murdered, and the children began to evict the loft. Among other things, lots of notebooks and papers, photographs and all kinds of documents. Bego Ariznabarreta Orbea read in blank the astounding memories of his late father's war, and realized the treasure, the importance of testimony.

The result of the analysis of the father's memories is his robust article: Civil War: Trauma, grief and memory in autobiographical testimonies. The militiamen Juan Azkarate and Luis Ariznabarreta on the northern front. The website of the

Sancho el Sabio Foundation is already available to anyone who wants to read it. It was during the pandemic, in the spring of 2020. As we cleaned the loft of the paternal house, we found our father's manuscripts, dedicated to the 1936 war. His father was Luis Ariznabarreta Zubiaurre, from the Espilla de Soraluze farmhouse. During the war he was in the Amuategi battalion, a militia, for fifteen months. In his father's papers we have the direct testimony of the time: chronology of his passing through the front, prison, military documents, photos, list of deaths from unknown causes, names of soldiers, verses... and two curiosities: A Chinese in the Basque army, and Russians and Chinese in the Basque army.

Did your father tell about the war in Spain?

Yes, always! In times, on weekends, in our house, our meals were extended, our parents put us on the table and forced us to be in the evening. My father would tell through those intervals his story of war, of anecdotes. He did not tell us directly about the grief or the pain of war, but he did it indirectly or intermittently... He silenced a lot of things, but I would say that silence conveyed his pain to us.

Do you, even if your father does not mention the greatest cruelties of war, do you assimilate the pain he has suffered?

I think so. For example, our father died in 2003, after having spent the last year sick, at age 88, in peace. The topic of historical memory began to work hard with the new century, as they were disobeyed. When I heard about them, tears came to me, I was moved. "It will be my father's death and mourning! I thought then, but now I know it wasn't the grief, but the pain of the war that he passed on to us. War and the pain of war have always been present at home.

.jpg)

As for the roles I found after my father's death, the more present was war!

But until I read those roles and knew what war was, I didn't realize how traumatic the war was, what happened in the Spanish Civil War. After reading my father's story, I went to the Sancho el Sabio de Vitoria Foundation library and I read a lot about the war, and in my home library I have a whole shelf full of books and war information. Now, in Gaza, I see that war is recurring, and that wars have to stop, I don't know how, but that we have to stop. I, for example, have written my article against violence and war.

I read to you in the article that my mother also got bad. That was Rosario Orbea Gallastegi.

He had been a war boy counting his own in the evenings of our house, and he didn't shut up. I'll tell you more: I also made the recording. It's wonderful, it talks about your life and war, among other things. Our late mother was very happy and counted many adventures of war, all raw. They were three sisters and were in Saint-Étienne (France) with their mother. I will also write about my mother, study her story and leave it written for our descendants.

-He's a Chinese with a great story. They called it changai, because it was from there. The father says he fought with them and he had the same fate."

In many houses, war has not been told. In the past, both my father and my mother said ... That doesn't

mean they told it all. I didn't know my father had taken the guns. I've been a little silly about that, because it's war. Our parents made resistance and defense. One side attacked and the other, resistance and defense. It has to be clarified. But, of course, the two sides acted. But my father didn't tell us stories of guns. I recorded several stories to my father, but none of them from war. When we found their papers in the attic, I was very interested.

Among other things, he has studied anthropology. How have you been able to write about your father, a close man? At one

time, the researchers said that when there is great affective proximity between the author and the object of the study, one cannot write objectively. In current anthropology, on the contrary, it is considered that this closeness can be enriching, as many elements come into play that are not taken into account by conventional research: interest, emotions, nuances... On the other hand, by objectivity, today we know that objectivity is not an immutable reality, a fixed thing. Objectivity is simply the path of the author ' s intentions. It is about conducting a close investigation and, at the same time, maintaining the analytical distance.

Objectivity from subjectivity...

That's where my father's subjectivity and subjectivity come in. The important thing, however, is to analyze things honestly. From my first line of work, I say who I am, who I am the daughter, what my studies are, what my questions and my goals are. If someone reads my work, from the very beginning they will know who is writing, why and for what. I'm trying not to fool anyone.

You say you made a recording to your father, though you didn't get to ask about the war. However, they also made the recording.

After the death of Franco, Carlos Blanco Olaetxea took over the band in the early 1980s. In the Basque Government's Civil War guide, I found a reference to my father's recording. I had a surprise, a nice and beautiful surprise. It has a duration of 90 minutes and is located in the Historical Archive of the Basque Country. My father wrote in a notebook and was astonished, saying that he would never believe that that day would come, that many years later someone would come to record with the war. I think that helped in part to overcome the trauma of war. And on the other hand, writing also helped him a lot. Also music. The guitar, the singing, the creation of verses... was very therapeutic.

Nowadays, there is talk about the therapeutic value of writing in relation to writing.

That's what they say, yes. I met our father always writing. Even when we were growing up on the mountain, my father would take a piece of paper, or the wrapping of a chocolate tablet, and he would write something. Sometimes I'd keep those papers and sometimes I'd throw them away. I don't know. But I do believe that writing was very therapeutic, as therapeutic as group walking, because I sang in a choir -- that's how I sang in Euskera -- and I participated in a tertulia of gudaris or militiamen to talk about war and politics.

I think the count helped my father overcome the trauma of war, in part. And, on the other hand, writing also helped him a lot.”

They met in society and talked about war. At the remittances of yesteryear he also told things and stories to the family. But you told us you didn't even record anything specific about war.

It's true. I finished my anthropology studies the year my father died, and I said, “This is a brand! I haven't recorded my father at war!" I felt it. At the same time as the grief, I got the questions: “Did my father kill anyone?” I know that this is war, that they kill each other, but that my father kills no one... But I didn't ask him directly about the war, and he didn't even talk about killing anyone, so I stayed with that doubt. In the recording, for its part, it clearly states that it shot and that, in addition to that, for a while, it says that in Lemoatx they killed a huge lot. “We made a lot of death.”

It was about the great felony.

Yes, but below: “...but with us we have done much more”. I was surprised, because there is one author, the historian [Ronald] Fraser, who wrote the book Remind Him You, Remind Him Others. He interviewed over 300 soldiers and wrote 235. Fraser says no one ever told him he'd killed anyone. It's amazing that Fraser says no one killed anyone and that my father, in the recording made, clearly accepts that he participated in people's deaths.

The title of your article bears two names: Juan Azkarate and Luis Ariznabarreta. Luis, your father. And Azkarate?

Friend of his father. Both were of the same age and belonged to Soraluze. When the war came, they were twenty years old. They were volunteers, militiamen, at the Amuategi battalion. We don't know much about Juan Azkarate, except what my father wrote. Juan's parents were Eulogio Azkarate Bustindui and Victoriana Treviño Azkarate. They had two children. Alberto and Juan. My father and John Azkarate walked together on the fronts of the war, and being in Etxano, one next to the other, a couscous beat John and smashed his head. That's what my father says. He was buried in Amorebieta-Etxano, and when Aranzadi [Society of Sciences] disobeyed Etxano in 2024, there were those who died on May 16, 1937. Among others, the remains of John, although we still have to identify those remains...

.jpg)

What about John's [Azkarate] family? My parents and my brother, I mean.

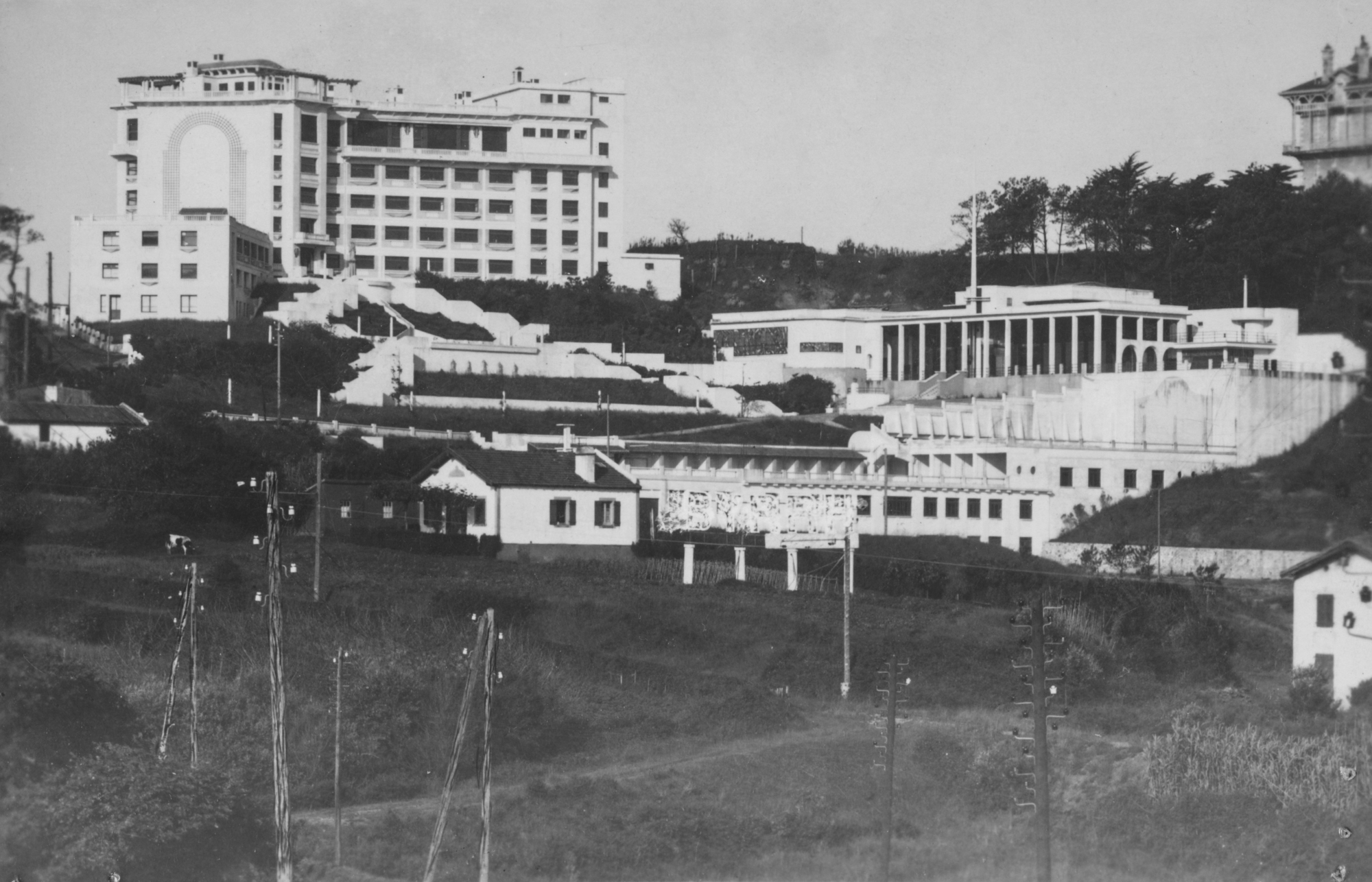

John was killed on the front lines in 1937. His father, Eulogio, died a prisoner in 1938. In this situation, and as a result of the atmosphere experienced in the village by the Francoists, Victoriana stopped going out in the street. The case is that the mother and son were transferred to Santa Águeda [Psychiatric Mondragon]. The mother was 60 years old, her son was 23. There they lived until their death; Alberto, for example, died in 1987. Both lived in Santa Águeda, although separated, in two different places, as men lived on one side and women on the other. The war was a disaster for the family of Eulogio and Victoriana. There has not even been anyone who has told his hard and hard story.

"When they were in Etxano, one next to the other, a horn hit John and smashed his head. That's what my father says. He was buried in Amorebieta."

It's terrible!.. You also want to write two other papers, Aitarena and Juanena.

Yes. On the one hand, Chinese. The father says that they were in Gijón (Asturias, Spain) and that they took a Chinese to their squadron. He's a Chinese with a great story. They called it changai, because it was from there. My father says that Xangai fought with them and that he was lucky, or worse, because my father was four years in jail, and Shanghai, six. I studied Xangai's story, followed his steps, and I want to write his entire story. Along with that, or on the other hand, I'm going to write my mother's to analyze women and the Civil War. And another thing, very important ...

Tell it yourself.

I don't like the word bando [alderdi]. I am the daughter of a militia, but my intention has not been to show the desire of one side or another, to bring to light the suffering of war, the traumas that arise. The mother also told us: “I don’t want you to live a war.” My father saw the dead right and left, he also killed them, and I wanted to write against wars, which cause great suffering and trauma. We think we've left behind these traumas, which have been forgotten, but there they are, we still have the traumas and symptoms of war that our parents lived.

.jpg)

.jpg)

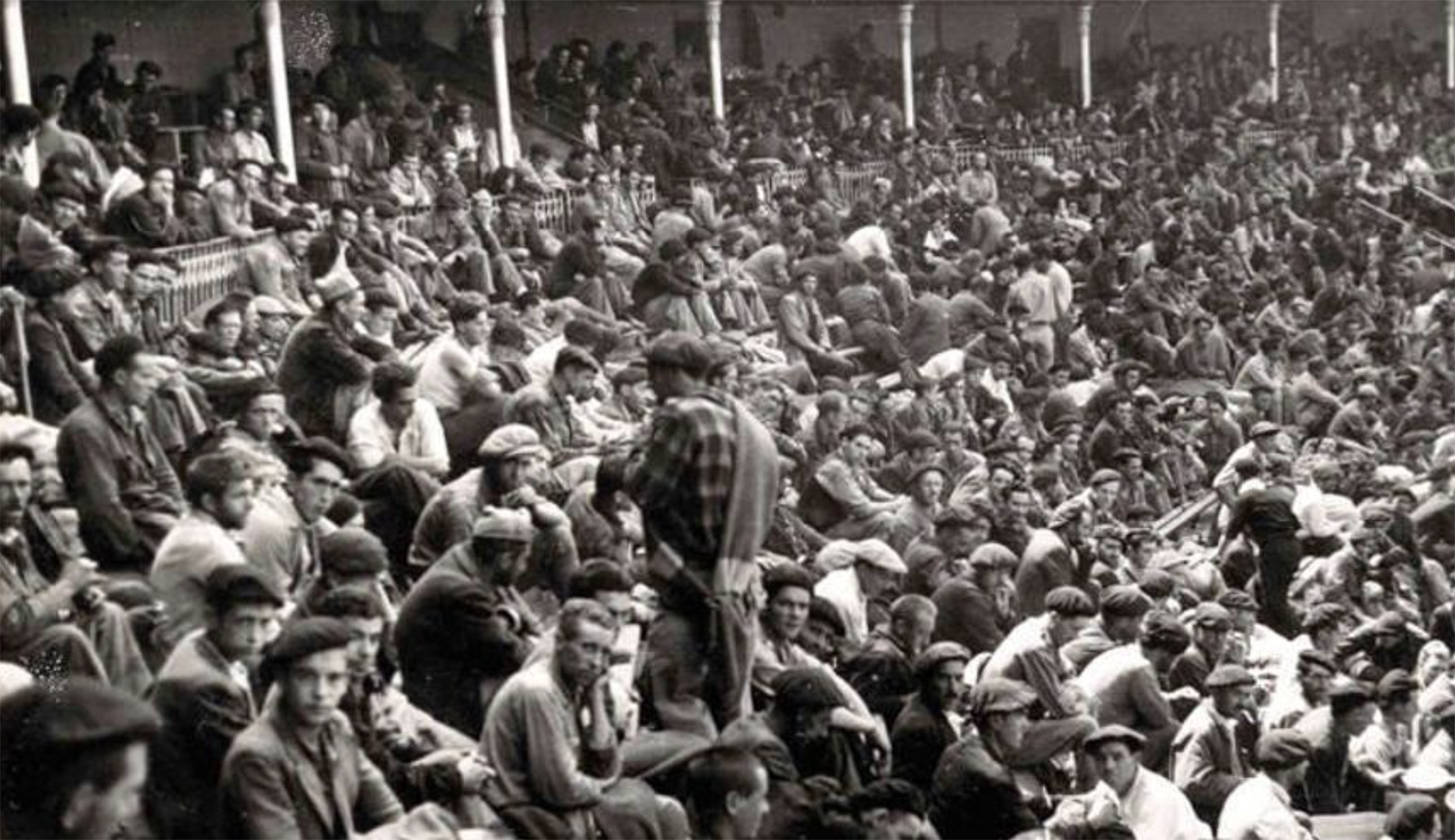

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.