"Linking lives more anxiously and more impatiently to our generations"

- A kiosk, in the midst of crisis, between the giris of Benidorm. And behind the newspapers, by turns, two people who differentiate ages and perspectives of the world. With these contrast elements Lizar Begoña has developed his first novel: Against the sinister world. We have met him in a similar environment. In Zarautz, a few meters from the beach.

The name of your first novel is against the infamous world. It looks like the title of a manifesto.

When I introduced the project, Itzalkina was called in the sun, but when the painter Ainara Alkorta sent me the cover, with very vivid motives, etc., it seemed to me that I needed something to contrast. I think both characters have an attitude like this against the world. I don't know to what extent that world is miserable, because they both live in a more or less comfortable world. But both have this attitude of opposition, one for the survival of the business that is its kiosk, and the other for the internal conflict generated by the relationships.

Now we are in Zarautz, and looking around us, this could also be the location of that kiosk you installed in Benidorm. What has been before: Benidorm or history?

I think the first impulse in the novel was the desire to talk about paper content and digitization. I met the kiosk as I turned around on this subject, and that was the first physical location. Then, they put my eyes on the photographs of Martin Par in Benidorm. I could settle in San Sebastian, Zarautz or any tourist town on our coast, but I think Benidorm is a rather anti-grass, not very romantic place, and it looks like a handle for humor. We all have an image of Benidorm, even without being in Benidorm. I've used that symbology.

In art, fashion or music videos, there is a tendency to search for beauty in elements that have been considered bad taste or ugly. Does Benidorm also have this attractive infamia?

Yes, there has been a tendency of this kind to give new meanings to some locations, there is a search for a touch of beauty in recent years. And I think that's also drawn me. In the process I have also discovered the history of Benidorm. In the 1950s, he had a tourist boom, but before he was a humble fishing village. All of a sudden, what's out there now came out of the hand of Mayor Pedro de la Hoza, and there he stayed, a place in the form of Disneyland, cardboard. Located in this scenography, the kiosk has crossed with other ideas.

The novel has two narrators. Pilar, who supports the kiosk of Benidorm, family business, and a young man without a name, who goes from Euskal Herria to work in the kiosk. Has it given you a problem with having to develop two voices? I've

taken the opportunity to show that contrast between digitalization and the paper press as a metaphor. It has allowed me to reveal the problems of the two generations and to show the contrast continuously, in a quite symmetrical and parallel manner, throughout the novel. But getting into the flesh of more characters multiplies the work. I ventured to bring in the two identities, but I realized it's hard work: you have to create each one his own physique and his inner world. It is true that I have suffered more with the character of Pilar Colom. Entering an identity of another generation requires more imagination.

It is a scuba diving, among other things.

I wanted to give him such a curious test. When I have been the recipient of other content, films, books… the characters have attracted me more personality and physical identity. That's why I attributed that quality to him. I think it has given him something, and it has been an excuse to get closer to the reader.

Through Pilar, the issue of custody also has room in the novel.

It's the thread of personal experience. With Alzheimer's, we've lived very closely the evolution of my grandmother, and I wanted to bring a character like this. I've seen my mother do care work, and that relationship also exists in Pilar and her sister Dolores. It has been a way to get into the skin of a woman of another generation, from what I have seen and lived.

The young man also has a close character: PAU, who experiences love and relationships in a very different way.

I wanted to give the two characters a second character next door, yeah. In the case of the young woman, she needed another more fragile identity that looked at love from another side. Pau brings that wildest and most extreme character. Through it we talk about phenomena such as Tinder, the disappearance of someone after knowing him…

The character of Pau has no gender identity definida.En the texts that have

been written about the book, it is said that it is the story of two working women, but I do not say that they are neither young nor Pau women, and that has been a conscious option. In general they have been read as women, but that which I wanted to include in this way, without specifying, not from exoticism, but because there is another concern that I have in mind.

You have also turned to the children of the protagonists.

It's been a gesture, a maneuver, to complete the characters, and I've also known those characters more. They've been written passages with quite a sense of heart; there's a lot of my memory in the young character's past. I've enjoyed it, it's been a way of looking for pleasure in writing. Researching in memory has been something that fills me a lot and excites me. Then, whether it's necessary or not, whether it works or not, I don't know, but I've enjoyed writing that.

He says that he wanted to collect some kind of testimony from his generation. What characterizes this generation?

I think I'm talking about a group of people who experience the break with the previous generation, rather than a stretch of age. There's been a leap from an ideology of generations before us. We may not get married, we will not live love in the same way… Our generation has raised some things that the previous ones did not raise and the next ones will raise something else. I believe that there is a broad collective, living in a certain instability, which is not linked to anything.

"Physical distances have increased, but we're always there, present."

How much does that have of liberation and individualization?Being

different or doing things differently doesn't mean we do them better. It may seem that apology is being made, or that I claim another way of loving, but I'm not in it. I believe that in our ways too there are problems, which we are often clumsy. We will not get married, but we may never know what we want and we will always be lost. From that concern I have brought this subject to the novel. What do we do now? What advantages and disadvantages does it have? I wanted to deal with these questions without giving definite answers.

One of the starting points of the novel is the concern about the changes that digitalization has brought. Has this influenced our ways of relating?

I think so. We spend a lot of time gluing to screens, and it's undeniable that digital has somehow impacted our view of the world in general, including relationships. We're all online, here and now, accessible to each other. We live a great paradox: we are alone, but surrounded by people, physical distances have increased, but we are always there, always in some way present. Maybe we're more intolerant of loneliness, and maybe we're more connected with more anxiety and more impatience.

The ‘not wanting to associate with anything’ you mention, I would say, has to do with the digital reality ahead of us. It seems to me a nice parallel to that of music. Today, it's hard for us to keep a full album. We heard loose songs, maybe not whole. We jump from one author to another, sometimes without knowing who the author is, and something tells us that the song is not good, for example if we are not convinced by a single note of a melody, we change. We have at hand the whole fan and we have tattooed the mantra "there is always something better". With all the pleasure and anxiety that this generates.

The character of the young woman has a concern or question: What will the old age of our generation look like?

I have another worm. How are we going to tell this? What are we going to tell the next ones? And the next ones will read us? It is still a mystery. Sometimes I think that we will not be so different, that in the end we will be a replica of the previous ones. But maybe not, maybe we can create something different.

Another possible side damage of digitalisation: we don't have time to read. Looking in front of your fellow generation, do you worry about this?

I have lived with caution. But responsibility doesn't mean it's bad. I look at it. It's true, I approach reading groups, and the people who come up and the people who have an interest are not my age. And I enjoy the same thing, that's not a question. The question is: Will my voice not reach my friends? Or my relatives? Those who make music may have a wider audience, but they have literature -- part of it is in decline, next to the paper press.

You have written, however, to your generation.

It's a talk that makes me suffer because it's my evening. It's not the audience I hope for, but I'm sad not to be heard in our generation. I know it is in part, but it is not a rule. In part, there's a desire for communication, and that's why I write. But I feel a little bubbling.

You use Instagram to make your columns known or your book reviews. Instagram is the new kiosk?

Partly yes. These are kiosks intended for the sale of press and other articles. Where do we get this information from? Or where do we take an idea of the present? How many people of our age go to a newsstand or a store to buy a newspaper? Very little. What do we do? We explored Twitter or Instagram and created an image of the world. Some can access the news, and others create this image in the context of information bombing. I am also there and I am actively involved.

"There has been a leap from an ideology of past generations to ours. We may not get married, but we may never know what we want and will be lost.

You've written the novel through the Igartza Scholarship, which means working on a time horizon. Has it been a spur?

Yes and no. On the one hand, I believe that this eternal pressure can help. Otherwise, maybe it wasn't over. It is true that I have also suffered, especially in recent months, because I did not know how to end, there are so many ways to end … But I think it is a physical and temporal limitation that has given me the excuse. I have suffered, but it has helped me.

After two books of poems, this is your first novel. Do you like what I did?

I still need a certain distance to say that. I note that this has been much more welcome than the other two books, probably for gender issues. But I've still experienced it a little bit of fear and shame. In any case, I think it has been something that I have written from the heart. I've tried to find my voice, throw away my closest reality and not write far away from me, even if the place is strange. I believe that internal things are close, written honestly, and in that sense I have remained calm.

Beginnings and finals have their importance in their work. The Japanese Gepardo in his poem book gave you a sign of an end to the beginning and end of the beginning. Now you have closed the novel with a decision made by the two protagonists at once.

I think I've been very chaotic in the process. It has been a writing process on the one hand and on the other, without the need to follow a script, and I have not had the plot in my head either. It's been more to go creating scenes little by little. The union between the beginning and the end has helped me to close. Because I haven't been in control throughout the process, in the end there had to be a second lid to close the sandwich, and I think the characters needed a certain climax.

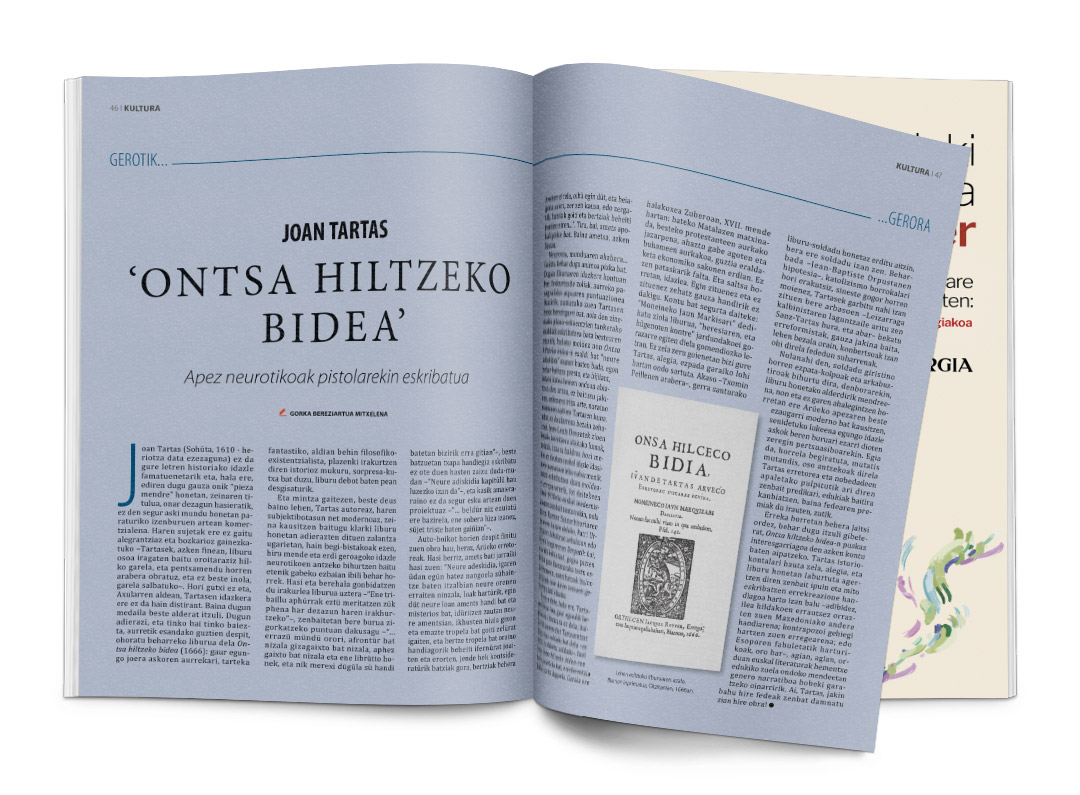

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)