Silent, mute, white... and brave

- On 23 February we went to Zaragoza (Aragon) a friend and I. She's a teacher of Early Childhood Education and I'm a literary energizer. Album! The course organized by the association (structure that brings together independent editorials that publish children's and youth literature) caught our attention. We were received at the Library of Aragon; under the slogan Audacious Books, they had a two-day program. Books without words, silent or mute books. We then refer to the books that have the image as main (and almost unique) support, and we will detail those that have been analyzed there in the article.

On the first day we had a round table with several editorials. They taught us why and why to publish daring books, what that decision means, how the materials are selected and some examples published by members of the organizing association of the course. Being original and interesting, we felt the desire to have the books in our hands and the fear of the hole that we were going to make in our pocket. On the other hand, Anna Castagnoli told us what the historical use of abstract art has been in children's literature. He is a great speaker, passionate and passionate.

On the second day, we also did a number of activities, all interesting. But I would like to bring to these pages the intervention that has encouraged me to do this article. The latter presented us with the work directed by Rosa Taberno and researched by María Jesús Colón: The album without words and the construction of a reading community in the public library. In the library of a small rural town, 41 children aged 3 and 11 years gathered during a school year. The children gathered together in small groups to read speechless albums. Do you know the etymological origin of the word album? I also met her there: she comes from Latin and means white.

In these sessions, the children read, interpreted and commented on the books while researcher Colon was under observation. One of the first things he saw was that the boys and girls who used the tools and skills to understand the written texts used to understand the meaning of the images. In addition, albums without words primed orality and collectivity. In fact, the reading of the images generated a multitude of interpretations and the situation forced them to contrast hypotheses. In this way, they created an inclusive community of readers: the albums facilitated participation above age, origin and academic level.

He gave us examples of books and we were able to hear the audios of the programs. At first, the children's readings were very descriptive, but little by little narrative interpretations were made. Once the reading was finished and an interview about what was read, a re-reading was made, with a more distant story: they talked about the feelings of the characters, commented on the relationships between the characters or added something that the images did not say. In addition, they shared doubts, raised questions of reflection and established connections between ideas. In short, complex narrative strategies were being used to read images, read written texts: description, interpretation and critical analysis.

In one of the examples we were able to hear, it was clear that the children made the decision to interpret the album, each putting the voice of a character and inventing interviews, someone assuming the role of storyteller, etc. Colon recounted that they began to draw spontaneously. And it gave great value to the function that the no-word albums had to boost their creativity. Reading habits also changed in the village where the experiment was carried out. Both children and families identified the library as a meeting point, influenced by the reading habits of the people of the town.

Colon spoke in a fairly flat tone, but as I counted the main ideas, the examples and conclusions of the research accelerated my heartbeat, my brain got going and I got really interested. I was very pleased with what the speaker told us. I'm going to bring some examples to this article.

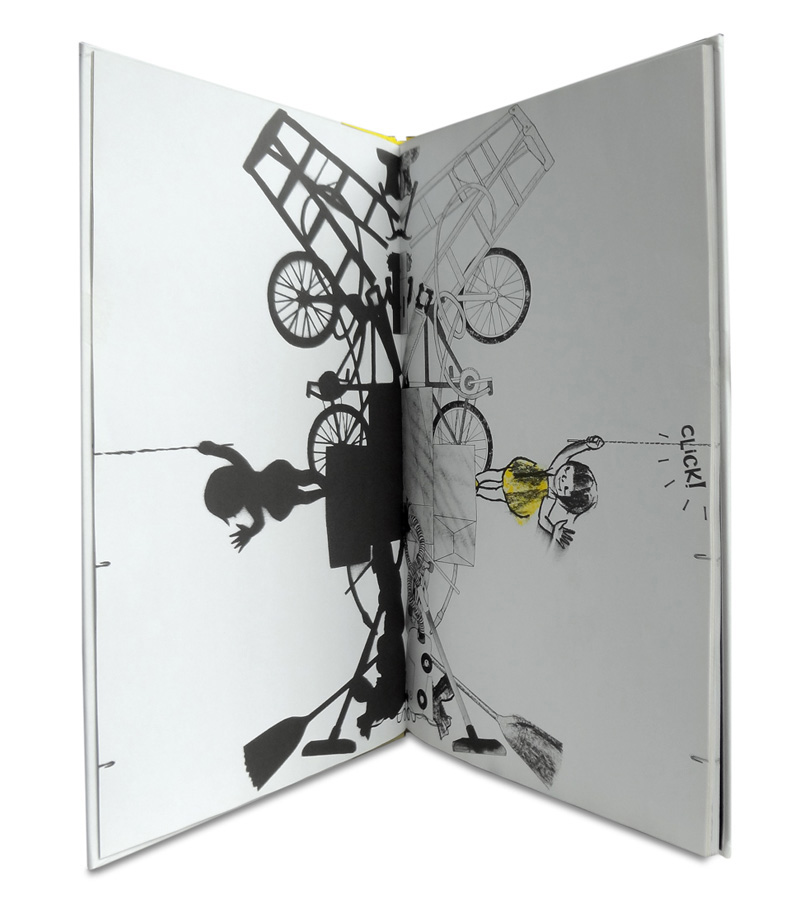

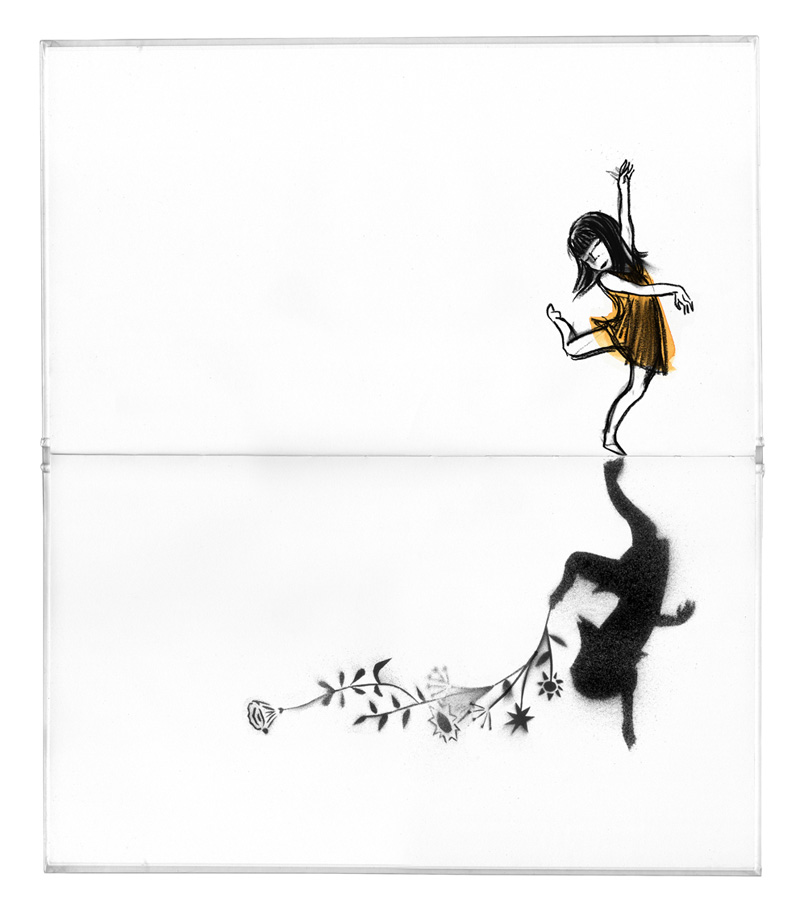

Adults have quite a lot of prejudices about illustrated books, and if they're speechless, even more. Among the no-word books, however, there are very interesting materials for adults. Those of Suzy Lee are well-known: Mirror (Corraini, 2003), Wave (Chronicle books, 2008) and Shadow (Chronicle books, 2010) are some of the many names that the journal has swept through. What the three have in common is a reflection on the border. What are the limits between the real and the imagination? Is there a boundary between them? What dimensions do dreams have? And what are the limits of the book? It is in this ambiguity in which the author maintains us, in which the reader stands at the boundary between the light and the deep. Like the protagonists, the author has stated that the readers have also used their own limitations to enjoy and play, remembering that it is also a reading game.

Around the conference, I learned that the winner of the Bologna children and youth literature fair was the book Kintsugi by Issa Watanabe. It was a surprise. Kintsugi is a Japanese word known as the art of repairing broken ceramic pieces with resins and noble materials, in order to expose fractures and give a value of beauty to the fragile life of the piece. Then he read me and I loved it. The author's mother is also an illustrator and the poet's father. Watanab illustrates poetry without writing a word. On the black background, clean and elegant illustrations come to prominence. Stimulated by what I had learned, I thought I had to try in my hands the newly published book: I gave it to a friend and he was reanimated by the desire to write. In the reading groups we have proposed without guidelines and have made collective readings. Like the children, we have performed the first descriptive readings, then the interpreters and interviews have been started to arrive at the critical analysis. Although we've started with a resistance point, laughter, games and awe have taken the place.

We also went home that way from Zaragoza. Happy, empty pockets but full heart.

I've been enjoying a book lately. In a very short time I have read it twice; the first with pure delight and the second with a pencil in my hand. Hoces de piedra, martillos de bronce, by the Spanish archaeologist Rodrigo Villalobos, aims to explore prehistoric society to answer... [+]

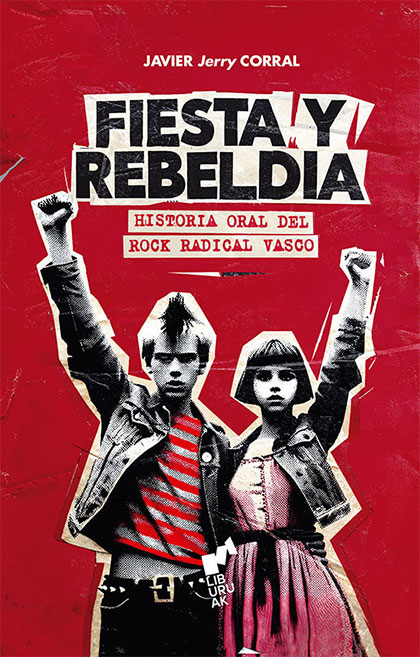

Party and recreation. Oral History of Rock Radical Vasco

Javier 'Jerry' Corral

Books, 2025

------------------------------------------------

Javier Corral ‘Jerry’ was a student of the first Journalism Promotion of the UPV, along with many other well-known names who have... [+]