"Something happens in the world when we collectively say we lack someone"

- In April he moved to Bilbao to give a lecture on healing scriptures, inviting the Masters of Social Sciences of Models and Research Areas of the UPV/EHU. He had to say: study sociology and history, use the file to write and tell the life and feminicide of his sister in The invincible summer of Liliana. On the eve of receiving the Pulitzer Prize, it is clear that literature does not cure, but it can be a form of justice.

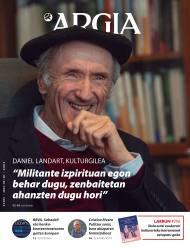

Cristina Rivera Garza. (Tamaulipas, Mexico, 1964)

Writer and researcher. He is currently a professor of creative writing at the University of Houston (USA). He has written several books in different genres. In addition to those mentioned in the interview, here we recommend another: The indomitable deaths. Necrowriting and disappropriation [Rebel dead: necrowriting and expropriation] (Consonni, 2021). He has been awarded several awards: last year the Gutun Zuria festival in Bilbao and this year the prestigious Pulitzer Prize.

I have heard you on more than one occasion that it has taken 30 years to write about Liliana’s femicide. What factors influence Liliana's invincible summer writing? I personally have needed 30 years to do my grieving process, but I always point out that society has taken so many years to tell stories of this kind differently. In addition, there are several points. A book is not born once, but is born again and again. On the one hand, I heard the

performance of the LASTESIS [The Rapist Is You] group, and I understood that we already had a language to talk about this, and that there was another auditory ability that I could take otherwise. The severity of the pandemic also influenced the feeling that we would suddenly die. For various reasons, I noticed that I was willing to write this book, and that there was an environment ready to embrace the book, and that somehow, it was necessary to write to keep opening a conversation that belongs to us all.

What reception have you had? I didn't expect

Liliana to be so generous. It has been articulated with the new generations of today, not only with regard to concerns related to gender violence, so constant in cities, in the public space, in the private space, but also with regard to the protection of one's own freedom. There is also a certain understanding: young people see the importance of being free to explore our worlds. I was very surprised by the esteem. It was not just political interest, social interest. Liliana has been highly valued and now has many more brothers in the world. I like it.

Mina is still there, but is grief not so lonely now? Follow the grief. I talk a lot about the American poet

Alice Notley, who says that literature does not cure. But this book has been able to turn that private grief, silently shut up, buried under the shame and guilt of society, into assisted grief, into collective and even collaborative grief. That has not brought relief, I believe that relief should come from the hand of justice, and as for legal justice, at least, there has not been. The alleged femicide is free, has never been tried, the arrest warrant remains in force. So that part of justice has not been accomplished, but we are working on another justice, on memory and on truth, and from those practices comes this other form of grief. Liliana Rivera Garza's name is out there, he's constantly called, and we know it wasn't homicide, but feminicide. We know it was a femicide, not just a murderer. One way of justice is to bring those concrete terms and tell this story differently. This dictionary is very important. I care, my parents, who are already dominated, care a lot. It's not silly. Remembering Liliana as a narrative of passionate crime is radically different from the silence imposed by patriarchals.

"I think relief should come from the hand of justice, and as for legal justice, at least, there has not been."

You are a famous writer, this book has received several awards, it has moved a lot… Has there been no answer from Mexican justice? When we started presenting the book in Mexico, together with the publisher, we opened an email address so that, if anyone knows anything

about the type, we would write there. And I got a lot of messages: several women wrote to me, they were with him and they were abused, and I also got the link to a funeral, one of those digital funerals that were done in a pandemic. Photos of the alleged femicide appeared, from childhood to death, and that link stated that Mitchell Angelo Giovanni died on May 2, 2020, a name he allegedly used since he fled to the United States.

Like the relatives of many women who have suffered the femicide, I have had to investigate on my own, because there is still little will to get into this type of issue by Mexican justice. I hired an American detective who found it true that a man named Mitchell Angelo Giovanni died strangled on May 2, 2020 in southern California. But what we have to see now is whether Mitchell Angelo Giovanni is really Ángel González Ramos, and that has to be done by Mexican justice. They have all the documentation, they have my testimonies, they have everything and they have done nothing. Note, in this case there is a book, we are also talking about the subject in Bilbao, and they have done nothing: what will happen then to the other cases, with which there is no dialogue or books? Once again it is clear what kind of impunity exists and how this impunity allows even more crimes of this kind.

In your speech yesterday you were asked about revenge. It's a

very complex, very complicated emotion, and we often have it banned, especially women. When I refer to revenge, I mention it in the sense that the writer Annie Ernaux did in her speech to receive the Nobel Prize: she said that she started writing to avenge herself…

By class. Of course. And at least as I understood it, that meant telling stories that haven't had a

place in public debate. So I understood revenge, not in the sense of that other American cliche, in the sense of taking the gun and killing people, but in the sense of taking Liliana's story and articulating it in public space, bringing her name to our lives. And I expressly decided to put his picture on the cover of the book, his face, among other things because I wanted him, if he lives the femicide, to see him, to face him. And my message, now as then, is that Liliana is stronger than the femicide, that Liliana will survive after her death, that people will remember Liliana's name and that the guy will rot when she forgets, under the protection of her cowardly relatives, who also lived, protected by her mother and sister, who helped her escape.

There is therefore a great anger, an absolutely legitimate anger, the same anger that leads us to say that everything must be burned. I perfectly understand that anger, I understand it in the heart of my bones. And I also think it legitimate to say that Liliana's life and history, that life that this guy wanted to crush and eliminate, actually stays here, and will last a lot longer than the guy. In that there is strength, solidarity. I am interested in this aspect of revenge.

"And I decided to put her picture on the cover of the book, among other things because I wanted if she lives the femicide, she to see her, she to face her."

Liliana is shown alive in the book. There are his writings, testimonies from his friends… That has a lot of strength. When cases of gender-based violence or violence occur, the first thing that happens is that the fact is suppressed, even today, although we have much more suitable environments and languages to collect these stories. Other times, these events

are usually numbers, statistics, which is also a form of erasure. Finally, death, or death, may become the axis of everything, forgetting and eliminating that behind these violent deaths there were complex, rich and joyful lives.

In the book I was very interested in talking about Liliana's death, social factors, personal factors, etc. that caused that death. But above all, I wanted to bring her life, because I think if we tell the lives of all the women we've lost, we'll have a lack of them, and if we see which places left empty in the spaces that we live in, it'll be different, it won't be like they're continuously made visible. There is something in this longing, as it is said in English. There is something in that “we miss you” community. There's a political force there, I think something happens in the world when we collectively say we're missing somebody.

Just before Liliana's invincible summer he published another book, Autobiography of Cotton, where he

analyzed the history and lives of his grandparents. They were from northern Mexico, like you. I think there's a relationship between the two books. The invincible is part of a series of Liliana’s summer books, in which I have blatantly mixed fiction and nonfiction. The first of this series was There was a lot of mist or smoke or I don't know that [there was a nut, or smoke, or I don't know what]: my personal approach to the famous Mexican writer Juan Rulfo.

How was that approach? In addition to his books, I went to the places where his writing came about, walked his ways and reflected on his labor decisions. Controversial decisions: among other things, it created dams in some places, removing land, sometimes forcefully, from indigenous communities. After this book came Autobiography of cotton, where he mixed archival research, field work and a

very material vision. I think a cycle is closed with Liliana's invincible summer. Now I want to go back to fiction, but you can only fictionalize fiction.

You're another person after writing those books. Same thing.

So we'll see what happens.

What is he writing now? A lot of things! I'm with a narrative book, see what comes out. I also have a novel: it has created

me great headaches and still needs time. On the other hand, with regard to issues related to the Maria Zambrano Scholarship, I am conducting interviews with Latinx writers, especially in English, to see what has happened to his Spanish. These writers are bilingual, and what has been said many times about their writing experience is that they have lost a language. But I believe that they have not lost a language, but that language is also working on their English texts in different ways, but that we have not been able to see and analyze those forms. So I'm doing a series of interviews, and I hope soon a book will be made with that.

You yourself analyze the literature and what others write. For me it

has always been very important, as a writer, to know my traditions, where my books are located, with what or with whom they speak. As a writer living in a female body, in a society with great gender inequality, and I was not born in central Mexico, I'm from the border. I mean, when I started writing, the main notion of writing corresponded to white men in cities, middle class, etc. I wasn't that, and I think it was almost natural for me, to be able to think about my writing, to criticize those major mandates of writing. So from the beginning, I had that critical calling.

I noticed Liliana's material presence when I worked with her papers. Well, I'd like to highlight that materiality of our ghosts and apparitions, which is what I work constantly.

One last question, but it's not mine. Yesterday my friend wrote me in the notebook. What is your ritual for death and life? Ufa. But we can spend thousands of years talking about that! Liliana's presence is constantly exacerbated and where I least expect. It spends all the time and I say it drives

me because I have that feeling. It's not preconceived. But I have managed to guide, in a way, how I respond to these demonstrations. I used to take a lot of sustenance. Now I've created a kind of relationship. Yesterday I commented that I noticed Liliana's material presence when I worked with her papers. I would like to highlight that materiality of our ghosts and our apparitions, which is what I work constantly.

What about life? The rituals for life are many, right? Over the years, keeping quiet and having a space of peace have become fundamental to me. I find it very useful to walk, I also try to swim, but walking is for me

a way of meditating, a ritual. I can't write for a long time, two or three hours a day is enough for me, and I think you have to prepare physically for it, it's a great effort. It's physical effort. I've found these ways to go.

SCk Zerocalcareri egindako galdera sorta eta honen erantzunak, jarraian.

Euskal Herriko literatura gaztearen eta idazle hauen topagune bilakatu nahi den proiektu berriaren inguruan hitz egingo dugu gaur.

Rosvita. Teatro-lanak

Enara San Juan Manso

UEU / EHU, 2024

Enara San Juanek UEUrekin latinetik euskarara ekarri ditu X. mendeko moja alemana zen Rosvitaren teatro-lanak. Gandersheimeko abadian bizi zen idazlea zen... [+]

Idazketa labana bat da

Annie Ernaux

Itzulpena: Leire Lakasta

Katakrak, 2024

Decisive seconds

Manu López Gaseni

Beste, 2024

--------------------------------------------------

You start reading this short novel and you feel trapped, and in that it has to do with the intense and fast pace set by the writer. In the first ten pages we will find out... [+]

Istorioetan murgildu eta munduak eraikitzea gustuko du Iosune de Goñi García argazkilari, idazle eta itzultzaileak (Burlata, Nafarroa, 1993). Zaurietatik, gorputzetik eta minetik sortzen du askotan. Desgaitua eta gaixo kronikoa da, eta artea erabiltzen du... [+]

When the dragon swallowed the

sun Aksinja Kermauner

Alberdania, 2024

-------------------------------------------------------

Dozens of books have been written by Slovenian writer Aksinja Kermauner. This is the first published in Basque, translated by Patxi Zubizarreta... [+]

Sometimes I don't know if it's too much. That we're eating a pipe, that we're talking about anything else, that we're bringing it up. We like to speak aloud, to leave almost no pause, to cover the voices, to throw a bigger one. Talk about each one of them, each one of them, what we... [+]

Puntobobo

Itxaso Martin Zapirain

Sowing, 2024

----------------------------------------------------

The title and cover image (Puntobobo, Wool Bite and Rag Doll) will suggest mental health, making the point and childhood, but more patches will be rolled up as the book... [+]