"Working a simple garden in school gives us a context to talk about the problems we have on the planet."

- Iratz Pou, a student of the UPV, has researched the gardens of the Infant and Primary Education centers of Vitoria-Gasteiz. How many schools have orchard? What use do they give, with what objectives and with what motive? Do they take pedagogical and didactic advantage of the garden? We have worked with Pou and Igone Palacios, director of research and professor at the UPV/EHU: “To see us safe in the garden as a teacher we need models”. At the end of this interview we collect the experiences of the Errekabarri and Zabalgana centers.

The study analyzed, first, the presence of school orchards: 82% of the centers studied had a garden project and 18% did not. How do you value it? What kind of orchards have you found?

Igone Palacios: The results are very positive, as the sample is important, both quantitatively (22 centers of Infant and Primary Education in Vitoria-Gasteiz have been analyzed, 40% of the centers of ESO in Vitoria-Gasteiz) and qualitatively (we did not go to those we knew had vegetable gardens, public and concerted centers of different neighborhoods have been taken into account in the research. The presence of orchards in schools is important, so most schools have the opportunity to promote their relationship with nature and their associated projects in daily life in the school itself. School orchards are an excellent teaching context, we can become a new class to practically address many themes and areas.

Iratz Pou: The garden is a very basic place for our survival, suitable for obtaining food, and the presence of orchards is such, that schools have advanced in integrating the relationship with nature, knowledge and attitudes in the learning process. The orchards we've found are different from one school to another, but in general I've seen well-ordered and well-equipped orchards.

You have also analyzed the use of school orchards.

Pou: In general, the schools make good use, although in some schools the use of the garden is not fully internalized. The key is management: in some centers the garden is not included in the school roadmap, it is an additional action, and in others, the garden is included in the curriculum and has in it many didactic activities. In these cases, it is easier for the professors of the different subjects to turn to the garden to deal with their field.

Palaces: It is particularly positive that schools and teachers have been found who are very actively involved and are already receiving positive experiences. Because it is necessary to tell that it is possible, to demonstrate that many things can be done without being experts in horticulture, both to make the school a widespread practice (not a couple of teachers) and to extend it to as many schools as possible. In some cases, it is impossible to go to the garden with 25 children, but it is possible, although not easy, and if you can go with the help of another teacher it is even more enriching. Sharing and disseminating that many schools are working on this activity helps others to encourage them to break that path, because we too learn as a model, and to see ourselves safe in the garden as teachers we need models.

Pou: "Working in the garden is a great learning: in a city like Vitoria children often do not have the opportunity to know where the food they eat comes from"

Specifically, what do schools want to work through the garden and what can they work?

Pou: I live in a village, in contact with nature, but in a city like Vitoria, often children don't have such a possibility to tighten their relationship with land and nature, or to know where the food they eat comes from, and all that in school is beautiful. Therefore, working in the garden is an important learning, but it also serves to address other fields, especially from some stages, considering that there are many professors and subjects. Schools also put these two main ideas in mind the garden project, but in reality they often find it difficult. Although working in environmental gardening seems a simple concept, the work that follows is profound.

Palaces: For our well-being, for our survival, we need nature, but these connections in the city are hard for us to see and the garden helps to recover it. Studies indicate that in cities, although little to foster contact with nature, this relationship is reinforced, it helps to become aware of the causal effects of what we do, which are very disconnected in the current system.

Moreover, orchards allow for upheaval, relationships, intergenerational dialogues, the union of cities and rural areas, reflection on food sovereignty (at least symbolically, because most of what we eat is not going to be from that area. Working a simple vegetable garden gives us a context to talk about the problems we have on the planet.

Once on this basis, as we are a school, why not go further and give it a second lap, why not take advantage of the vegetable garden to teach mathematics (from weighing the compost to pulling it, passing mathematics to everyday life), to work languages (how many words are there to say hoax? ), to make the drawing… to give context to what you have to learn, to get from the abstract to the concrete and to give meaning and a cause facilitates learning and understanding. In addition, leaving the four walls and giving the lesson in the exterior space gives air and motivates the students. For example, from Early Childhood Education we can take advantage of the transition to Primary Education because it seems that in Early Childhood Education the movement is very important but in Primary Education we can only be sitting in the classroom. It is important to redefine spaces, give a different meaning to the exterior spaces and use teaching as a space.

Palaces: "Orchards allow the Auzolan to weave intergenerational tertulia, unite cities and rural areas, reflect on food sovereignty"

They used to talk about teacher uncertainty. If teachers receive more training, would the vegetables be given more performance?

Pou: In the study I detected that it has directly influenced the teachers who have received training in their view of the garden, they have seen that in their subjects they can use the garden in a didactic way. This training is not widely taught at school, so the responsibility of the garden often rests with certain teachers and parents, not all teachers participate.

Palaces: At the UPV/EHU we train the teaching staff, we teach how to teach in the garden, and these sessions are very welcome, the need is also very complicated, although it is very difficult to train with the teaching staff because there are many training sessions directed to them and little time (if the session is in school hours, for example, it is usually difficult to come). The first step is for the teachers most involved to go to these courses and then disseminate it at school among the rest. Very soon, on April 17 we have the Mathematics course in the garden and know the biodiversity of your school on May 15-16.

In any case, will future teachers already have this training as it is taught in the Teaching career? In the career of Pou: Magisteritza, we have been able to go to the vegetable garden in the course of Nature Sciences, and we have also come down to the garden of the campus to make a

project and train ourselves in their return with some other professor, like the one in mathematics.

Palaces: Yes, we do many things that were not done before. We're going to run away a few hours from the Natural Sciences, and that experience remains for them when they're teachers. Even if you don't remember it exactly, it's easier to repeat what you've already done, that reference is already made by the candidates. In fact, we know the Elementary and Early Childhood Education students who have learned with us, who are now doing these jobs in their schools. Our limitation is that the subject of Natural Sciences has hours in Magisterium.

Pou: "In most schools, cultivated foods are consumed by the students themselves and prepare in the center several dishes"

What are the main deficiencies in the use of school orchards?

Pou: As mentioned above, the garden often becomes the responsibility of certain professors, which limits the use of the garden.

Palacios: The other day we were with the members of the Council of Orchards of a school and told us that they need more recognition, more academic liberations, among other things to receive training or to adapt the curriculum to the garden. In fact, only BeAtarra now has school hours dedicated to this type of task [BeAtarra is the professor responsible for innovation in each center]. For me, the most important thing is to value the garden, to achieve a significant learning process every time we go to the garden, and to do so we must organize well what we have to do, feel safe and give importance to what we do (in number of workers channeled, in time, in ratios).

What interesting experiences have you found in the centers studied?

Pou: In most schools, cultivated food is later consumed by the students themselves and several dishes are prepared in the center. This causes illusion in children. I also found interesting the work done by some schools on compost with the organic waste generated. And in the case of those who have a pond near the garden, the project is enriched in the observation of biodiversity, in measurement, in care: they measure the evolution of both the garden and the pond to make successive readings.

What do you think would be the best use of the garden?

Palaces: In addition to what we have been discussing throughout the interview, it would be best if the students of all levels could use the vegetable garden and dedicate four or more monthly sessions with each group. However, depending on the school (and on the resources and conditions of the school) it can be a good use, and in that way we try to help and contribute ideas. What do you need to make good use of the garden? Would a protocol help you? A specific appeal? Research has also enabled us to identify the needs and where to intervene.

Beyond the garden, there is a growing number of initiatives to introduce more green areas into schools’ backyards, including forestry schools. Environment, nature, food sovereignty… Is awareness of these issues increasing?

Pou: The restoration of green spaces in schools is an obvious trend in recent years, you only have to see how many play spaces have been remodeled and renaturalized. After all, there is a widespread tendency to gradually return to the place that humans have removed from nature. And with or without a garden, schools are taking action to develop that awareness.

Palaces: These green spaces have a great influence. We have another study comparing two centers that have used outdoor green spaces, one from the city of Vitoria and another from a town. Well, at the starting point, the local school students had a higher degree of knowledge and connection with nature, but after working with each other they achieved similar results, and in many areas the city students obtained a higher result. We should go deeper, but it gives us a hint: it is easy for children (people in general) to get in touch with nature and ask questions to strengthen their passion, interest and connection.

COLLEGE ERREKABARRI

“We teachers have the challenge of getting the class out into the garden, we are still very classrooms”

Errekabarri is one of the centers studied. It has 697 children and primary school students and all groups pass through the garden, from 2 to 12 years old. “We started from a young age: we came, we smelled, we planted…”, says Professor Patxi Ibarzabal. Every week they have a job associated with the orchard and they contribute to the whole chain school: for example, one group is going to turn to the land, and thanks to that another group will be able to plant in May and a subsequent group will collect the planting. And so they do the whole cycle. Horticulture is divided into three main tasks, which the entire school spends: planting or planting, maintenance and pond. “From there, it’s free to approach when you want to the vegetable garden, and when I’m in the vegetable garden, some people always come to me when it comes to playing, they ask me if I need help, what I do, if they can do something… It’s amazing what’s attractive to children. That’s why, even though it’s hard to get out of class at the pace we are taking, if we ask kids, they always want to come to the garden, and that’s what we should take advantage of.”

To systematize and organize both frequency and content is fundamental, since the orchard is part of the school project: “It cannot be my stone, it cannot depend on the sensitivity of some teachers, it is essential to collectivize, create network and turn it into a school project if we want it to be maintained and that what is really done in the garden is significant, and not a mere postcard,” explains Ibarzabal. The cloister often doesn't feel safe because we don't control this world and we think we need a perfect orchard, but from here we don't go to the fair, if some plants have corrupted it doesn't happen, it's part of the learning process. Courage and resources are needed.”

According to the professor, the disconnection of nature and vegetable garden is surprising: “Children cannot distinguish a leek. They know the fruits, but plants, vegetables don’t; buying everything in the supermarket is that.” Through the garden, it is sought, on the one hand, to observe nature and its cycles, sustainability and biodiversity, and on the other, to take the subject from the classroom to this space, and, on the other, to bring together multidisciplinary projects with a didactic objective. “We teachers have the great challenge, because we are still a very large classroom.”

COLEGIO ZABALGANA

“Lack of harvest is a problem, but it’s an opportunity to work with children.”

Zabalgana is another school studied, with pond next to the garden. It has about 700 students, all go through the garden and work with their families. It is noteworthy that they have five compostors of about 550 liters of capacity and that collect huge amounts of organic waste (considering the meals of students and teachers). They use it to see with students the reuse of waste or to analyze how earthworms compost.

Every year the vegetable garden between parents and guardians is planned, and every year the planted products are rotated: “Suppose this course we decided to plant tomatoes, then when we collect the tomatoes we can agree a tomato jam, taste the tomato with oil, make a salad with tomatoes and potatoes planted…” Professor Ibon Diaz explains, and with the compost we will complete the cycle, as the whole process is internalized. They also have medicinal plants.

“Since the age of 2, they begin to mix the earth, experiment, make small plantations… and live it naturally. Orchard is a good resource to get rid of many prejudices and increase knowledge. As age increases, more work can be done: the Alavesa potato is famous, but where does the potato come from? What about corn, tomato? How do Moon phases influence planting? If we are studying the Middle Ages in class, for whom was most of the harvest during feudalism? What fruit and vegetables do pupils born in other territories eat? For example, we tried to plant peppers brought from the Maghreb, but they didn’t go out.” All it is to get out of class is motivating for students, he says.

Zabalgana is an ecological garden. As last summer it was very dry and the sun glued to the garden, they barely managed to harvest: “No tomato, no fruit, hardly potatoes… and we had to work with children, we had the opportunity to talk about the climate. Frustrating is normal, it is also difficult for us to accept the result, and if there is no harvest we consider it a problem, but it is actually an opportunity to deviate from what was planned and work with the children what has happened. Teachers should also break some schemes.”

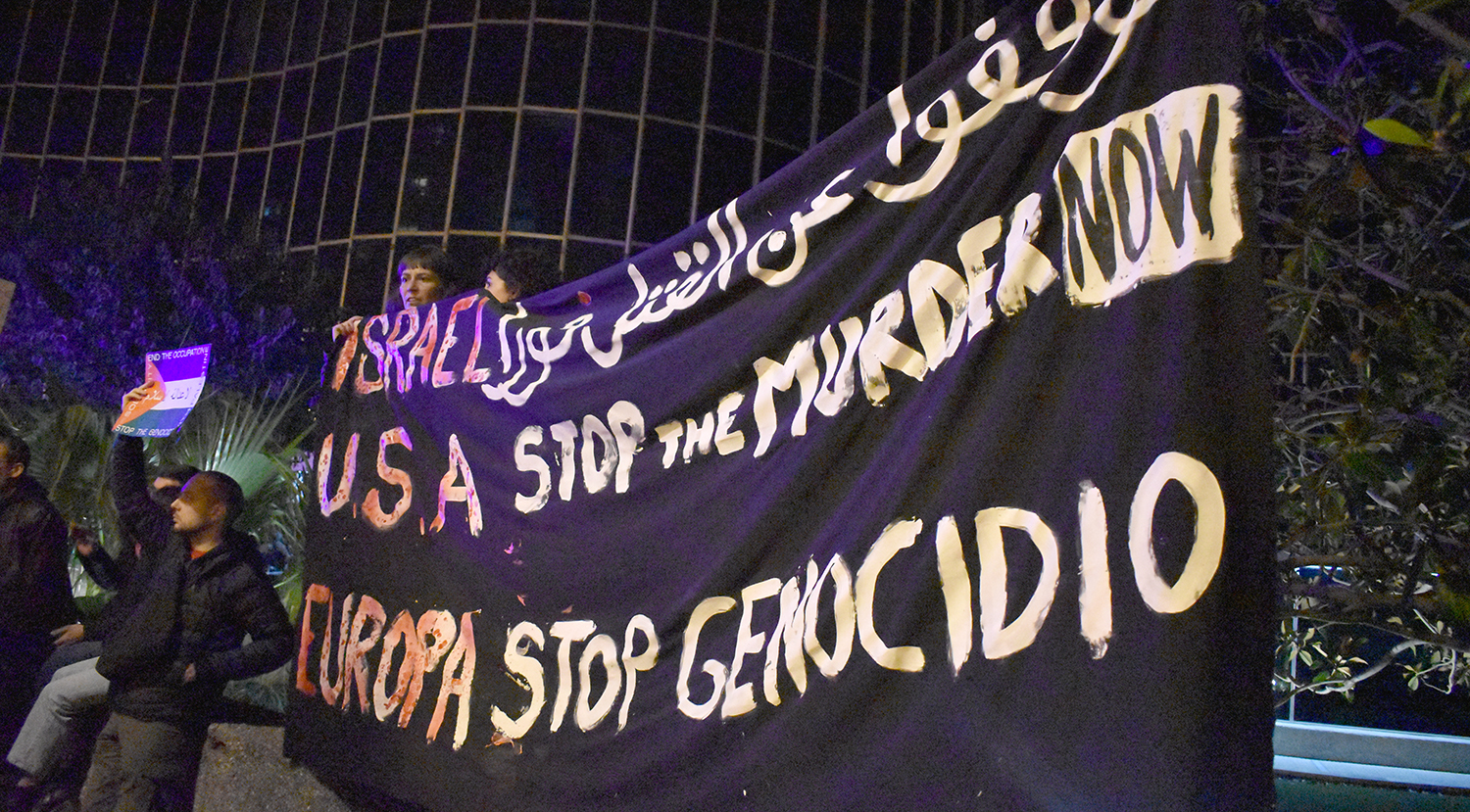

Public education teachers have the need and the right to update and improve the work agreement that has not been renewed in fifteen years. For this, we should be immersed in a real negotiation, but the reality is deplorable. In a negotiation, the agreement of all parties must be... [+]

Lehengai anitzekin papera egitea dute urteroko erronka Tolosako Lanbide Heziketako Paper Eskolako ikasleek: platano azalekin, orburuekin, lastoarekin, iratzearekin nahiz bakero zaharrekin egin dituzte probak azken urteotan. Aurtengoan, pilota eskoletan kiloka pilatzen den... [+]

Garai kuriosoak bizi ditugu eta bizi gaituzte, zinez. Hezkuntza krisian dela dioten garaiak dira eta, gutxien-gutxienean, aliritzira, ba aizue, 2.361 urte ditu gaurgero boladatxoak.

Ez zen ba debalde joan Aristoteles bere maisu maite Platonen akademiatik lizeo bat muntatzeko... [+]