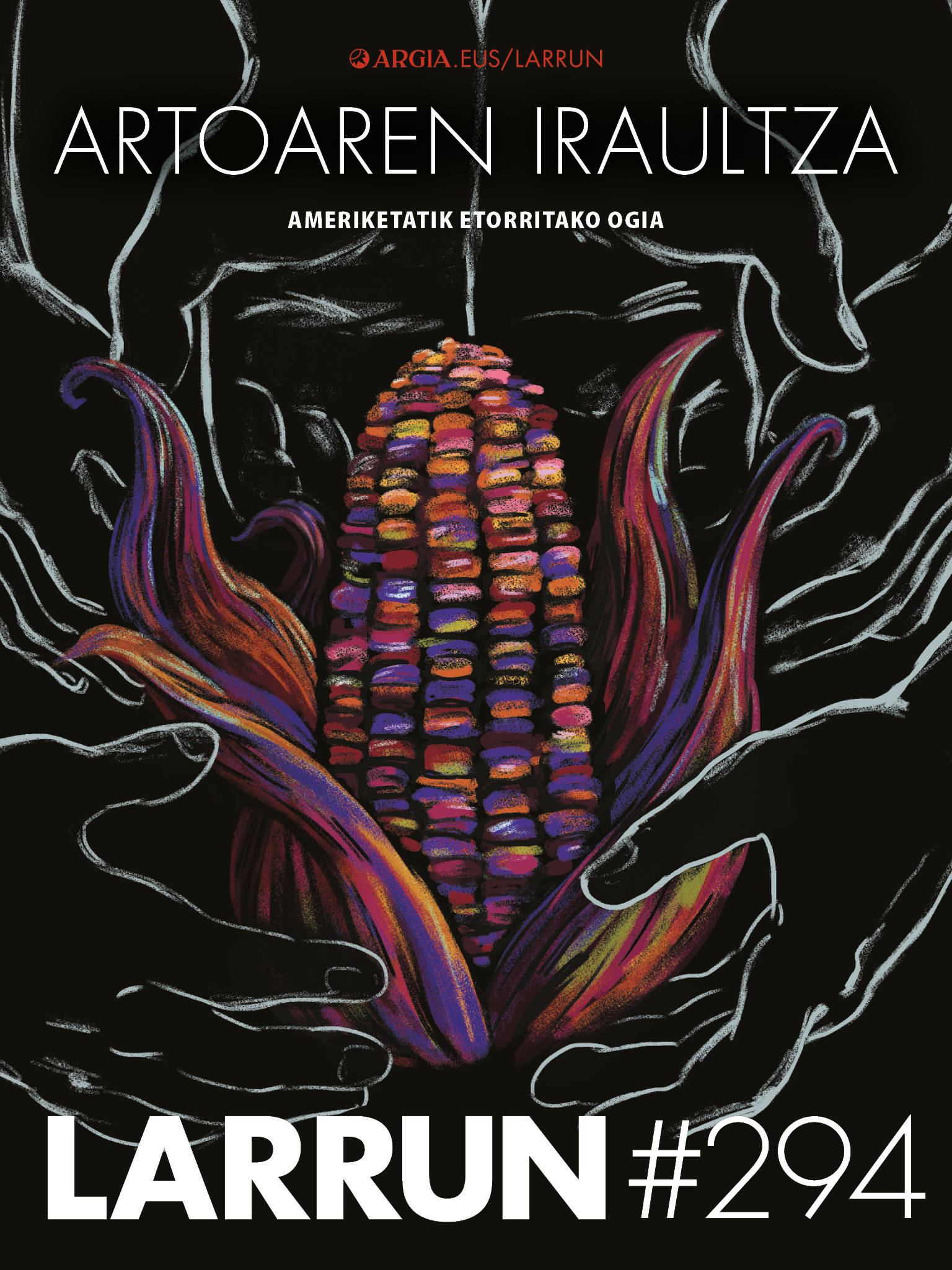

The Corn Revolution: American Bread

- From the days of cider that are organized in different localities to the Santo Tomás fair that defines the winter solstice, maize is an indispensable ingredient in any celebration of folkloric taste. The stems, decorated with dry mazorcas hanging from the tarpaulin tops, can be seen everywhere, for sale of flat corn flour pastries, considered a typical product of the rural environment. In popular sports competitions, for both children and adults, one of the tests that is never missing is the collection of fangos. Although it is almost no longer cultivated, in the chapters of many farmhouses you can still see strips of corn in autumn, in memory of that crop that was formerly a symbol of prosperity. Although we attach little importance to it, maize is a plant of great history that has influenced not only the lives of the Basques, but also their economy, culture and landscape.

On the Atlantic side of the Basque Country is an old connection between maize and farmland. The first ethnographers who took care of the life of rural societies in the territory saw it clear in the early twentieth century. Researchers such as Joxemiel Barandiaran (1889-1991), Juan Arin Dorronsoro (1892-1972) and Manuel Lekuona (1894-1987) described two-year growing cycles, based on the rotation of three main products in the same field: wheat, which was sown in November and collected in July, rapeseed – from manure to December – and maize – April. Sometimes crops such as alfalfa or alfalfa were introduced to feed the animals. These cycles were maintained until at least the mid-twentieth century, and their memory is still alive in many places.

Therefore, the landscapes that today appear green from grasslands were very different in ancient times, since they changed their appearance and color according to the time of the year. Maize was, in particular, a characteristic element of this landscape, with a much greater relative weight than in other nearby regions. This was reflected by the pioneers of Basque documentary photography, leaving images of great ethnographic and historical value, highlighting Eulalia Abaitua (1853-1943) and Indalezio Ojanguren (1887-1972). In these images you can see farmhouses surrounded by cornfields, almost like a sea that stretches to the horizon. On other occasions, the inhabitants raise the land layando, once the harvest is collected, while they feed on maize plants in the surroundings.

But when and how did this agricultural model emerge? Is the word ‘tradition’ as old as it suggests?

.jpg)

Maize (Zea mays) is an herbaceous plant of the grass family. It is currently the most produced cereal

worldwide, above wheat and rice, as it is used as food for both man and livestock. But to reach this situation, this plant has had to make a long journey, starting from its origin in Central America, travelling thousands of years and many continents.

The oldest archaeological tests of maize crops have appeared in Mexico. Local societies began domesticating this species about 8,700 years ago. Since then, maize cultivation has spread to nearby territories, stabilizing in Central America about 6,700 years ago and shortly thereafter in the northern Andes, especially in the Cauca Valley. Eventually, work was done in almost all the territories of North and South America.

Over the centuries, cultivation techniques were developed and new varieties were created, and maize became of great economic and cultural importance. In the sacred book of the Mayan peoples, Popol Vuh, it is stated that the first humans were made of corn paste. Before colonization, maize was called mahis, “the basis of life.” Hence the name this cereal received in several European languages: Spanish, French, Italian and English.

The oldest archaeological tests of maize crops have appeared in Mexico, whose societies began to domesticate about 8,700 years ago

But the real leap of corn would reach the end of the 15th century, after the arrival of the Spanish conquerors to America. Christopher Columbus wrote in his newspapers that the peoples of the Antilles cultivated a “similar to millet” cereal, which was cultivated throughout the year. So striking that in 1493 he took several seeds upon returning to the Iberian Peninsula as proof of his journey.

.jpg)

Attempts to adapt this exotic plant to the Old Continent were not revealed. In Castile, Catalonia and Andalusia, for example, the first seeds were sown before the end of the century. From there, the new crop spread to other regions of south-west Europe throughout the 16th and 17th centuries: Portugal, and through it the western colonies of Africa, the entire Cantabrian coast (7), Aquitaine, Savoia, the River Po plain, etc. Although initially it was used to feed animals, it was soon introduced into the diet of poor peasants, with great force; proof of this is that the polenta became a characteristic of the cuisine of northern Italy, or the boron and stalk of the Basque Country.

.jpg)

In Euskal Herria, it seems that maize first reached the coastal ports in the 16th century, and from there it rapidly expanded inland. By 1616, two-thirds of the total harvest of the year was for maize in some Biscayan localities – Maruri, Arrieta and Kortezubi – and another third for wheat. This inland coastal itinerary can be followed in detail in the Bidasoa Valley in Navarra. Igantzi was first cited in 1634, but had already had 20 years of experience. In Etxalar, it is also mentioned that after an attack by the French army in 1637 the maize landes were destroyed. In Baztan, the first references date back to 1640. In Amaiur, for example, at a meeting in 1644, citizens defined criteria governing the new crop to be “a good order and good governance”. Firstly, it would be compulsory at the beginning of April to close maize plantations in a given year to prevent the entry of livestock. Secondly, the harvest would be prohibited, even in its own section, even if the fruit is ripe, before the festivity of Domine Saindu. From then on, it would be up to the local authorities to inspect the existence of mature maize fields and to authorise the harvest. Thirdly, the infringement of these rules, or the removal of maize from outside plantations, will be subject to fines and penalties.

Maize adapted very well to the local climate and land, and without a delay moved other cereals, such as millet. In addition, the growing cycle of maize allowed alternating wheat in the same fields, reducing fallow and thus increasing crops. French Ambassador François Bertaut of Fréauville visited the Doneztebe region in the early 17th century and wrote that he was already doing so:

I spent a lot of time between the Pyrenees and the Bidasoa River. In some of the areas I looked at, you work corn like in Bordeaux, where the land has collected the bread and you sow the corn at the end of manure, from where it is collected.

At the same time, in 1625, Lope Martínez Isasti de Lezo also wrote that in some times of the year farmers ate corn bread.

A century later, the Jesuit Manuel Larramendi, in his book of Corografía de Gipuzkoa (1754), gathered that corn was “the bread of the poor and the peasants”. According to him, carboneros, woodworkers, etc. They were working on the mountain, not looking for wheat bread, but for corn, because it gave them more strength to work.

Maize was so successful in many parts of Europe that it replaced other cereals and took its name. The Basque Country is a clear example of this, displaced small cereals that until then had the name of corn and took their name off, creating for them the name of millet. The same happened with Galician and Portuguese (millo/milho) or piemonte (melia).

.jpg)

A REVOLUTION IN THE BASQUE RURAL ECONOMY Maize allowed for more

intensive cultivation. By alternating several crops in the same field without fallow, yields increased considerably, but at the same time, to prevent the intensification of the land, the growing quantities of fertilizers increased. Manure was produced in houses by mixing livestock manure with urine fern. After drying this fern in the tanks, it spreads in the fields in the form of manure to increase the organic matter of the soils.

However, fertilization also presented collateral damage, especially soil acidification. To deal with this problem, that is, to balance the pH of the soils, it was increasingly frequent to mix lime in the fields. The oldest references to this practice were found in the early 18th century: in the ordinances of Baigorri in 1704, in Bera in 1705 and in Lekunberri in 1709. According to the Larramendi Chorography, for half a century, the whitewash was spread throughout Gipuzkoa:

With all fertilizers and care, experience shows that areas are weakened in a few years. To combat it, every nine years it mixes lime to soils, with hardly any husbandry, which means a high cost of labour and wood.

In Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia, most of the territorial substrate consists of limestones. As a result, almost all the villages built their own seabed, which was managed in a decentralized way. On the contrary, where the limestone was not as abundant, as in the Bidasoa basin, it had to be brought from outside and in each locality there was a large stew oven that was exploited collectively.

.jpg)

In recent years, detailed inventories of these elements have been completed in municipalities such as Hernani, Zizurkil, Aduna, Aramaio or Etxalar. These works allow us to state that most of the kennels were built under the same model. Calcination furnaces are usually cylindrical, of considerable size, with a lower opening to introduce fuel and collect lime. The description and images of this typology were published in several 18th century treaties, including the Encyclopedia of the enlightened Diderot and D’Alembert, and can be a system spread throughout Western Europe.

Fern was an essential raw material for the production of the fertilizer needed for mixing with livestock manure and for the intensive pace in maize fields.

With the intensification of agriculture, the architecture of the dwellings was also adapted. The buildings were expanded and new spaces were added to adapt to the new cultivation needs. Thus, in the main facades large balconies were extended to allow the drying of corncobs and other crops of American origin, such as bell pepper, and the porches or flowers that preceded the portals acquired greater prominence for corn grain.

As a result of these changes, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, several villages were built or rebuilt on the Atlantic side of the Basque Country, forming a set of typologies known as Baroque villages.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The mills also received a great boost at this time. Although the structures used by streams and the strength of the rivers to grind the grain were common since the Middle Ages, since the 17th century new structures were built and the old ones were reformed to give greater size. In most cases, two mills were prepared, one for grinding wheat and the other for maize. Thus, the only structure served the production of the agricultural cycle throughout the year.

At the same time, agriculture spread to uncultivated spaces until then. Thanks to ethnographic and archaeological research carried out in recent years, a new path has

been opened to discover the development of these new landscapes. Logically, this evolution was not the same in all places, but was conditioned by the natural characteristics of each region - climate, relief, vegetation - and by the previous socio-economic history. Here are three concrete examples: the terraces built in abrupt areas, river basin drainage and coastal polders.

Forest headboards: the terraced systems, located in Mendialde and in the forest headboards, have since ancient times had difficulties in developing stable agriculture. Altitude, abrupt orography, fine soils, and erosion caused by rain or wind are some of the causes. Consequently, livestock

farming has had the greatest weight since the Middle Ages.

However, the introduction of maize from the seventeenth century on opens up new possibilities that allowed greater yields in each sector. In this context, the expansion of agricultural areas in many places was the most frequent way to build or expand the terraces systems. The method was simple: to spy on a strong slope area, a cut was made and a filling was made with the extracted soil, forming a staircase structure. In each case, on the edge of each terrace, stone retaining walls were built to reduce erosion and transversal drainage channels to regulate water flow.

.jpg)

This type of terraces are common in the forest headboards of Northern Navarre, such as Almandoz, Berroeta, Aniz, Ziga, Urrotz, Saldias, Eratsun, Areso and Arano. All these villages, stabilized on a complex and erosive geological substrate, have had to build terraces, called probes in the Baztan, wings(s) in the Malerreka, in order to develop a stable culture.

In Ziga, for example, the archaeological studies carried out by the Society of Aranzadi Sciences have allowed the first initiatives to build terraces in the Upper Middle Ages. But from the 17th century onwards, maize inflow triggered dramatic demographic growth that caused profound changes in the local landscape. The number of houses grew considerably and new architectural forms appeared with wider roofs and balconies to dry corn. In addition, the terraces were rebuilt, enlarged and enlarged to form staggered landscapes, today so characteristic.

In other places, the terraces are not attached to the population nuclei but around the bords disseminated on the slopes. This type of landscape developed in ancient communal lands during the Modern Age and is the result of agricultural expansion. In fact, the bords that until then were used for cattle ranching became farmhouses and, to be able to grow in their surroundings, small terraces were usually conditioned. This led, of course, to conflicts, as the reduction of commonly used forests and grasslands reduced the basic resources of the domestic economy. Fern was, in particular, an essential raw material for the production of the fertiliser needed to mix with livestock manure and maintain an intensive rhythm in maize landes.

Among the researchers who have delved deeper into this process, Patziku Peru has shown that the consolidation of these dispersed settlements in villages such as Leitza, Areso and Goizueta began in the seventeenth century and was reinforced between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that is, in the midst of the maize revolution. For example, in the mornings there are several fields reinforced with stone walls, which in some cases are still used for maize cultivation. Moreover, the rich culture of American crops, both maize and beans, has remained alive to this day thanks to oral transmission. This is the model that the early twentieth century ethnographers were able to observe throughout the Atlantic side of the Basque Country.

Inland river basins: drainage of valleys Unlike hills and hillsides, the terraces or valleys near the main rivers did not undergo intensive occupation in the Middle Ages. Without channelling the canals, the surrounding plains of the area

were subject to periodic flooding, which made it difficult to establish stable residential and agricultural areas. Except for exceptions, these were located outside the flooded areas and the only human structures located in the river ecosystems themselves were the ferreria and mills.

The situation changed considerably with maize input. On the one hand, the new cultivation was particularly well adapted to wet soils, and the aquifer of profitability facilitated the construction of infrastructure that until then would be costly: the planting of alisos and hazelnuts on the riverbanks to reduce erosion and maintain soils, the construction of flood defences, the opening of ditches to drain surplus waters, etc. In most cases, small projects were adapted in each case, but there are also examples of planned projects.

In order to cultivate the marshes it was essential to leave them out of the influence of the sea, which was achieved with the construction of polders

The case of Berastegi is significant. The village is located in a small valley crossed by the Elduain stream. The clays and plaster that make up the soil are eroded by the stream, in clear contrast to the mountain massifs formed by harsher materials in the area. To the north, the valley has a very narrow solution, with a series of waterfalls that sow towards Elduain. As a result, the valley is practically closed, the regatta flow changes have an immediate effect and the surrounding vegas are immediately flooded. Therefore, since the Middle Ages, most of the village houses have been built at the margins of these valleys and agriculture has developed in valleys with a high risk of flooding.

In 1765, the Berastegi City Hall asked the Royal Council for permission to channel the Elduain stream in a straight line “cutting the regattas that hinder the flow of water”. Under the direction of an engineer in charge of conducting the work, a network of trenches was opened and these wet valleys were drained. The result of these works is evident in the current landscape. The original winding path of the stream is completely missing and crosses the valley in a straight line from south to north. The canal is enclosed by walls to reduce erosion by water and to condition the intensive maizals in the surrounding vegas. In addition, a trench network leads the precipitation water to the main channel to avoid soil saturation.

.jpg)

Another interesting example is Bertizarana. It consists of three villages, Legasa, Narbarte and Oieregi, united by the Bidasoa River. Also in this case, the river has eroded the substrate clays, forming extensive campas on both sides. As the rainwater was trapped, these areas formed old swamps unsuitable for agriculture. In Narbart, for example, the names of the houses retain the memory of the vegetation growing in these swamps; in Altzugorea, Altzuberea and Altzume suggest the presence of the ally, and in Izua that of the ihi.

These swamps were drained in the early 19th century. The priest and botanist José María Lakoizketa received that his former pastor, José Manuel Agirre, promoted the drainage of these swamps, since then becoming “a field that guaranteed the well-being of several families”. Thus, this whole area is represented in the map of crops elaborated by the Provincial Council of Navarra in 1882 as a corn field and an apple. These uses were maintained until the middle of the twentieth century and have since been replaced practically by prairies. However, the remains of drains are also evident in the current landscape, crossing the entire area the “streams” or stone channels that lead the water to the Bidasoa from the mountain.

Costa: construction of polders on the Costa, the expansion of agriculture occurred mainly on the marshes of the rías. These

are special areas, which continuously depend on the flow of the tides, flooding during the high tide and being exposed on the low tide. As a result, they tend to have deep, rich sediments, but only halophite vegetation grows due to saltpetre. Therefore, since the Middle Ages these areas were mainly exploited as cattle pastures, a situation that changed radically with the entry of maize.

In order to cultivate the marshes it was essential to leave them out of the influence of the sea, which was achieved by the construction of polders. First of all, to prevent water from entering the high tide, they surrounded the entire perimeter by a dirt dam reinforced by a stone wall on the outside. According to the region, these dikes have been called leeches, trenches or mulberries. Secondly, for the drainage of inland waters a system of trenches was opened. These ditches led the leftover water to the ditches and were evacuated by open tubes or gates. Third, to improve the texture of dry lands, manure was mixed with sand.

This marsh drainage system was developed from the Middle Ages in countries near the North Sea, the Netherlands and England. In the Basque Country, however, it was not done until the end of the sixteenth century. The first attempts were made on the backs or marshes surrounding the large Aturri estuary, thanks to a special authorization granted in 1599 by the French King Henry IV III.ak. Thus, the areas that had previously been extensive grasslands were stabilized to cultivate maize, promoting strong economic and demographic growth in neighbouring villages.

.jpg)

One example is Gixune. The town developed from the Middle Ages at the confluence of the Aturri and Biduze rivers, focusing on the castle of the Agramont lineage. From the 17th century on, the barbarians close to both rivers dried up to cultivate corn. The old houses in the urban area built new lanes for the management of the new rural areas, giving rise to a unique habitat, ordered longitudinally over the riverbanks. Currently, these foams remain the richest farmland in the municipality and are mainly dedicated to maize production.

It is possible that Aturri's model has promoted drainage projects elsewhere. In the Bidasoa, for example, the first proposals for the creation of polders in the Jaitzubia district were presented to the plenary of Hondarribia in 1608, and the works began without delay. However, the works provoked the protest of the Irunans who denounced the loss of the bank ' s beatings that they had previously enjoyed freely. Although the conflicts between the two peoples would continue for three centuries, in general, the trend was the expansion of corn landes over the marshes. Consequently, by 1800, almost all the estuary marshes were dried, destined for intensive maize cultivation.

The evolution of the Barbadun estuary was similar. In the area currently occupied by the Petronor refinery a large marsh called Vega Mayor was formerly located, used by the inhabitants of Muskiz as a communal grassland. In this case, the drainage was an initiative of the aristocratic family La Quadra, which throughout the eighteenth century acquired more and more sections. By 1800, all the ancient marshes had also become cornfields here.

Elsewhere, the process was even faster. In Urola, for example, the City of Zumaia promoted in 1792 the drainage project of the large marsh called Basadiak, financed by a group of local investors. The works began two years later and by 1800 the whole area was drained.

Broilers were therefore an extended process along the Basque coast. As a result, several hectares were added to the cultivated areas of the coastal villages, formed by deep and fertile soils, and easy to cultivate for their plain character. Today, although many of these lands are swallowed by the urbanism of the 20th century or restored to the marsh situation, the economic importance they had previously still lives in the memory of many citizens.

A modern 'tradition' among the new products that came from

America in the Modern Age, maize quickly became of prime importance in the Basque rural economy. Its influence was so big and fast that in a hundred years it became the main food of the baserritars and the popular classes. The result of these changes are the ways of life, landscapes and gastronomic traditions that were codified at the beginning of the twentieth century as ‘traditional’, which still have a great symbolic value and which we reproduce at popular festivals.

The influence of corn was high and fast, as at one hundred years it became the main food of the baserritarras and popular classes

However, historical research shows that these models are totally modern, as they were the result of the colonial relationship that united the two margins of the Atlantic Ocean after the sixteenth century. This relationship was not unidirectional, but had multiple consequences at different scales, even for European societies. On the one hand, in the case we analyzed here, the opening of remote trade networks began to produce increasing accumulations of capital, which paradoxically caused a shift of the economy towards agriculture, as peasant and peasant classes were increasingly larger and excluded from these exchanges. On the other hand, the possibility of more intensive farming allowed the division of holdings and partial leasing. Thus, the growing number of peasants acted as tenants and land ownership was increasingly concentrated in hands, giving rise to a new class that lived from incomes.

All this is part of our history and heritage. At a time when rural life is eroding and our cultural memory is being lost, perhaps it is not enough to exercise memory and try to analyze the essence of those references that have shaped our symbolic universe.

Science through art

The importance of corn for American societies was very striking for the settlers who arrived after Christopher Columbus. Thus, since the early sixteenth century, an ‘exploratory literature’ began to be developed, in which references to this plant were very frequent.

It also aroused the interest of the continent’s intellectuals and naturalists when the plant began to expand in Europe. Thus, it is collected in several herbaries or botanical treaties of the time. The formation of catalogues of plant species has been an ancestral practice; in classical antiquity, the works of the Natural History of Pliny or the Medical Topic of Dioscorides became a must, copied and transmitted reference also in the Middle Ages, both in the Greek and Arab world and in western monasteries. Since the sixteenth century, in the context of the cultural environment of the Renaissance, European intellectuals began to rethink these works. Thus, new editions of these works were published, with new comments, lists of new species and decoration of beautiful illustrations.

The oldest herbalists who mention maize were published by two German doctors: Das Kreütter Buch (Strasbourg, 1539) from Jerome Bock and De historia stirpium (Basel, 1542) from Leonhart Fuchs. The latter also shows the oldest illustration of this crop. These two authors defined maize as a “foreign crop” and placed its origin in Asia, proposing its transfer to Europe by the Turks.

But, without a doubt, Discorsi (Venice, 1544), of the Italian Pierandrea Mattioli, was the most important hero of the time, who in the coming years will return to several languages. In the 1570 edition he introduced the first references to maize and defended its American origin against general opinion until then. It is clear that Mattioli knew the works of the Castilian explorers, as he also mentions the original name (mahis) of the Tainos language. It describes grains of different colors, red, white, black, brown, purple and yellow, and mentions the existence of different varieties.

The Generall Historie of Plantes (London, 1597) is another herbarium classic. It is a collection and adaptation of previous works enriched with various contributions from the author himself, among which is the cultivation of corn in his garden. Despite its doubtful first edition, in the new print of 1636, the plant came to Europe from America, following two paths: the first from the Antilles to the Iberian Peninsula and the second from Florida and Virginia to the British Isles.

Thanks to these herbalists, knowledge of maize and other plants spread throughout Europe. The illustrations accompanying the texts represented in detail the parts of the plant. Along with them, the culture cycle of the species, its characteristics and main uses were explained. For this purpose, both the descriptions of the explorers and the results of the experimental and observation works carried out by the authors themselves were presented. Thus, these special books, adorned with beautiful works of art, became a stimulus to the scientific debate, establishing the first steps of current botanical knowledge.

.jpg)

The importance of maize in Lapurdi

On the banks of the River Aturri, maize was specially conditioned and rapidly expanded during the Modern Age. Baiona's records perfectly reflect this development. Thus, in 1631 the military authorities of the plaza prohibited the peasants of the neighborhood from planting corn in front of the city gates, claiming that, in case of aggression, in the middle of the Thirty Years War, the enemies could be hidden among the great pillars of corn.

A century and a half later, the situation was completely revolutionary. In 1771, the city magistrates demanded the Crown Ruler to ban the export of specimens to avoid an excessive increase in the price of maize and bread. The explanation they gave highlights the importance already acquired by the crop:

(Maize) is a basic raw material that feeds the entire rural environment of our environment. Nothing else could replace it. If their harvest were lost, the labourers of all the parishes that lie until the gates of Shàlossa, Dax and our city, including Lapurdi, would be in the saddest situation. And that is that, used to the fast food of corn flour, they don't take wheat, barley or rye. They would not accept anything, and they would not do well; for the same price, we have seen one grain swap with another, as a corn fanega feeds as much as two fanatics and half wheat.

.jpg)

Archaeologists have discovered more than 600 engraved stones at the Vasagård site in Denmark. According to the results of the data, dating back to 4,900 years ago, it is also known that a violent eruption of a volcano occurred in Alaska at that time. The effects of this... [+]

Vietnam, February 7, 1965. The U.S. Air Force first used napalma against the civilian population. It was not the first time that gelatinous gasoline was used. It began to be launched with bombs during World War II and, in Vietnam itself, it was used during the Indochina War in... [+]

I just saw a series from another sad detective. All the plots take place on a remote island in Scotland. You know how these fictions work: many dead, ordinary people but not so many, and the dark green landscape. This time it reminded me of a trip I made to the Scottish... [+]

Japan, 8th century. In the middle of the Nara Era they began to use the term furoshiki, but until the Edo Era (XVII-XIX. the 20th century) did not spread. Furoshiki is the art of collecting objects in ovens, but its etymology makes its origin clear: furo means bath and shiki... [+]

In an Egyptian mummy of 3,300 years ago, traces of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that caused the Justinian plague in the 6th century and the Black Plague in the 14th century, have just been found.

Experts until now believed that at that time the plague had spread only in... [+]