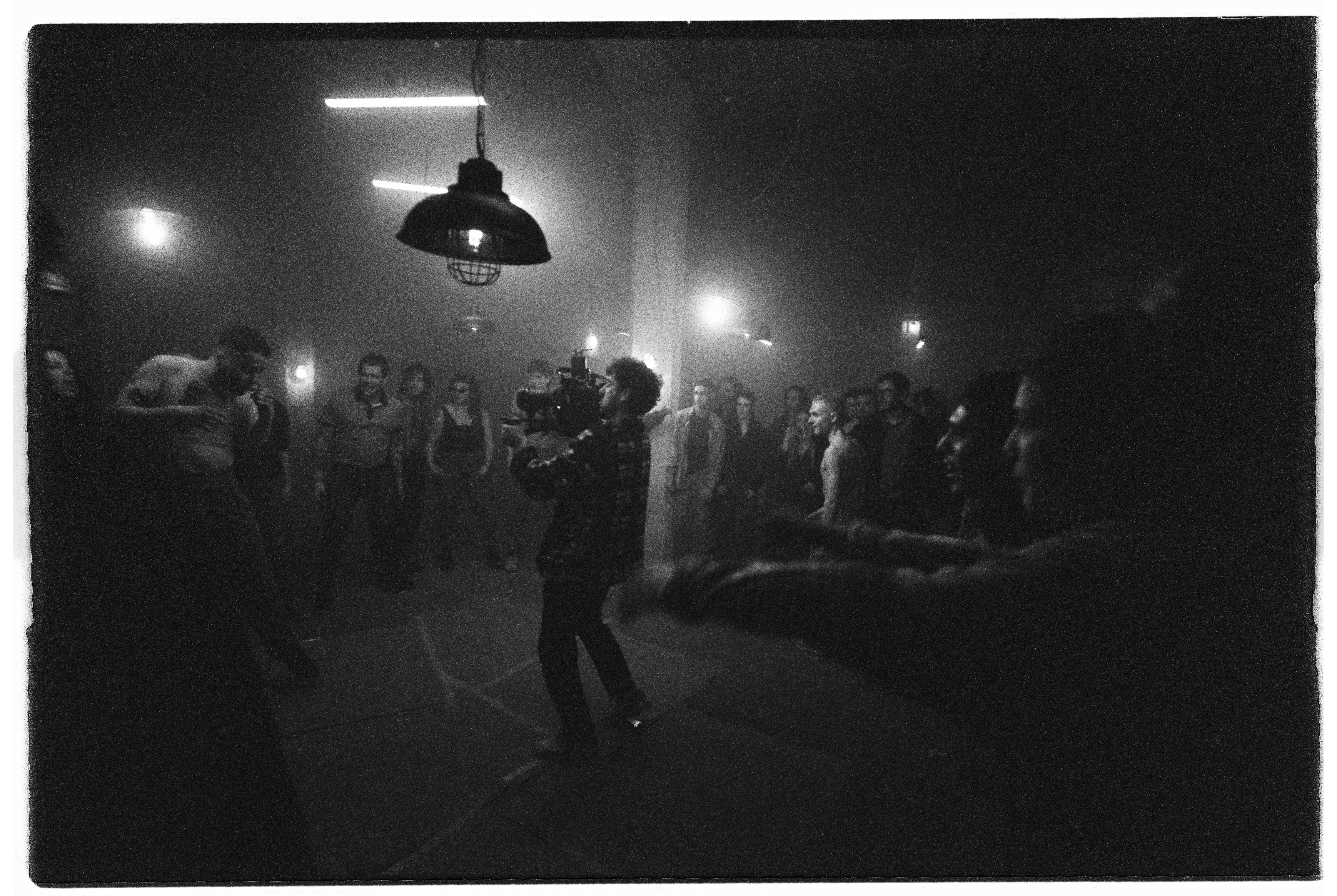

Looking at the video clips, across the lens

- The vast majority of the songs that make up the soundtrack of this world include expressly filmed images: video clips. Very close to musicians, a younger generation of audiovisual authors finds in this work what they do not have in the cinema or on television: a possible window where to demonstrate the possibility of formation, the freedom to risk and the capacity. But how do you take a song to the images? How much does that militancy job have? Is it possible to make video clips without sticking to the rules of the marketing game?

Music and video have been closely linked for at least four decades. The MTV network was created in 1981 and at the end of that decade the echoes of the format came to the Basque scene. But if you look at the video clips of all these years, there are reasons to differentiate contemporary from older ones. Since September 2023, Badok has received 62 new audiovisuals based on a Basque song. This is not the only excuse. There is no more than a review of the work of the young musicians who have highlighted: the effort they have made to add more layers to their artistic proposal is evident through the video clip. The trajectory of many groups or soloists has developed in parallel with a new generation(s) of audiovisual creators with older and friends. Leaving musicians on test premises, we have put the spotlight on those who work between camera and light.

From necessity to necessity Many are responsible for some taking a “new Basque music video” in their mouths. But if there's any name on this list, it's Arriguri. Xabi

Ojinaga, Asier Renteria and Ander Mateos formed the producer, and it was a video clip that united the three. Renteria and Ojinaga, members of the Urgatz group, came to Mateos asking for help with their video clips. It seems it was a good experience. Since its creation in 2016, Arriguri, despite the changes in the work team, has made dozens of video clips with a lot of mime, combining the trends of the most international video clips with the personal look. Although they also make other kinds of audiovisuals, they are the ones who have paid the most attention to musicians, or to them, and those who have subsequently led them to receive other petitions. It has not been the result of a plan, according to Ojinaga: “We don’t usually plan or think much. We met for the need to make video clips and even today.”

Although they left later, the path taken by the Badator study is not very different. Music is the starting point for many of the production works directed by Ander Merino and Thomas Ibarrola. The documentary Limoia by Izaro and the series of video clips that make up the album Cerodenero have been some of them. In these times when the importance of video clips is questioned, Merino claims its value. “There are those who say that in today’s music there is too much distorted or self-tuned guitar. The same goes for video clips. This is only one of the decisions of each artist.” He says that the use of elements that add the image gives a new dimension to the musician's proposal, and that he, as a musician, considers it essential to use it.

It enriches… Merina Gris, Hofe,

Zea Mays, Huntza, Izaro, Amorante… Badator and Arriguri’s are among the most acclaimed video clips of recent years. The use of analogue formats or fine work in photographic direction are some of the characteristics that distinguish them. But the path taken by them has been followed and expanded by many others. Ojinaga says they very much congratulate them on the video clips others have made for being their own. “Now there are more people than when we started and there are many young talents among them. Artistically it has changed a lot, it has improved.”

Zornotzarra Ane Berriotxoa is one of the videocapes inspired by the work of the Arrigúrica. He says that the main reason the video clip industry is strong is that the music scene is also strong. “The musical landscape is varied and rich, which is a great inspiration for audiovisual authors.” Although he is more interested in film, he is attracted to video clips. He has directed audio-visual songs of Eire, Olatz Salvador or Olaia Inziarte, among others. Along the same lines as Merino, he believes there is a very interesting network of illustrators, photographers, etc. They're around music, they're doing extraordinary work. “All these artists around us enrich Basque music.”

… but does not give money

Irudi enriches a song or a record. The other thing is if you can get the livelihood out of this work. According to Merino it is very difficult to think that, knowing that the situation of most musicians is precarious, one can live by making video clips. At least it comes in the study, they have only been able to advance with other works. “We are demanding with ourselves, and in order to be able to perform the level jobs that are currently being done, we always have to spend more hours than they will be charged.” The same is true of Arriguri, as Ojinaga has said. Until recently they did everything between two or three people, but in recent times they have met more and more specialized people. “This has led us to do more artistically voluminous work, but it has also made the work more complex and, of course, most groups do not have enough money to pay for that work.”

Ane Berriotxoa: "The musical landscape is varied and rich, which is a great inspiration for audiovisual authors"

Mattin Saldias is director of photography and musician. Learn first-hand about the work processes of many of the video clips that have been made in recent years. He says that many times they tend to want to do things as best as possible, but for that they have to put a lot on their side: assume excessive responsibilities, put their own material, ask for mutual favors… It is clear that this level of video clips they have created among their creators is not entirely sustainable. Not at least for those who have to pay the rent and the quota of self-employed. Ojinaga agrees that the minimum material needs are those that are supported by the people in the area for their cover-up, often with the ability to maintain them in these projects. “If it’s not very difficult.”

So what underpins that high level of video clips? For Saldias, the passion for doing things: “You can make video clips to test new techniques or material, or because you liked the idea a lot, or because you think a certain group deserves a good video clip. Sometimes it's enough to do this work, even for free. But it’s hard to keep that motivation for a long time.”

The scope of freedom Not to extinguish that motivation is related to freedom, according to

Ander Merino. Music groups are usually willing to receive proposals, and camcorders are free to decide on the development of their television or advertising work. “Without that freedom our work would lose sense. That keeps us in this.”

Ander Merino: "In order to carry out the level work currently carried out, you always have to spend more hours than you will charge"

Ane Berriotxoa appreciates as much freedom this process of developing an idea in collaboration with musicians. “You have to have a very active listening on both sides. I have to respect what the musician wants to convey, and from there, from me or from my capacities, after contributing. That is when the most special things emerge, when the two sides understand what we are doing and why.” Saldias perceives the need to look more at the initial idea: “The work of the director of photography comes later, but the first step is to work on the idea that conveys something. Doing well can save a lot of work and a lot of money, and we don’t always take it into account.”

Next step: fiction? Of course, Basque musicians have close to audiovisual authors who work with great talent and passion. Thanks to these video clips, networks of relationships have been created and many young people have been trained by sharpening their abilities and their gaze. Another thing is the direction to which the routes

that begin in close connection with video clips will be directed. Berriotxoa would like to make films, for example, because the dynamics of video clips often force us to work at excessively fast rates. In Arriguri and Badator, several (corrupt) attempts have been made to get resources to do fiction or documentary, but to achieve them it is not enough to show a rich video clip. They acknowledge that, however, they remain firm in continuing their efforts. Who knows: maybe soon it will be they who put the musicians’ door: “Hey, would you eat a soundtrack for our film?”

From MTV to Instagram

In order not to dazzle the reflections of today, it is convenient to explore the “damage video clips” file.

Nor do the experts agree in the search for the first pioneers. Some – and this is taken up, for example, by Wikipedia – note as a milestone the audiovisual made for the 1957 rock song Jailhouse by Elvis Presley. The fact that stabilized and standardized the video clip is clearer: the MTV channel was created in 1981, which offered video clips for 24 hours, becoming a defined marketing tool. And on the Basque scene what? He who writes remembers the video of the Korrika for the song Big Beñat by Fermin Muguruza. In 2001, Telmo Esnal and Asier Altuna, who then had a long career as filmmakers, directed this work that raised powders. But six years earlier, the 1995 Korrika had already had the theme and the video clip. By then, Eibarrés biologist Iker Treviño had already begun to perform similar works. It started in 1989, precisely for groups like Su Ta Gar or Cancer Moon, which were very close. That is true, also with little money. Remember that at that time Basque music had little audiovisual expression, and that the main motivation was to fill that gap. “We started playing with the language of the video clip and working with the aesthetics of the groups.”

Then yes, when he worked for groups that had contracts with giant stamps like Sony and Warner, Treviño managed to make his own life thanks to the video clips, always combined with other works. He also knew the time when video clips became a showcase for commercial brand advertising: as a filmmaker he had to look for ways to highlight a brand as naturally as possible. “It went from an expense to a benefit tool for some video clips.” However, he did not stop doing works for Basque musicians. He has put images to songs by Ruper Ordorika, Fermin Muguruza or Benito Lertxundi, among others.

Today he has less video clips – one of his latest works has been for the Anari de Vinu version, songs and love – but he is following closely what others do. He acknowledges that the appearance of Arriguri struck him with surprise and that he soon felt that “something new” had been going on for years. In this sense, he believes that they and those who have come behind have been able to work and adapt, with their risks, to these most globalized times in which social networks have so much weight. Nevertheless, he continues to perceive that the performance of video clips of Basque musicians will not be a good arrival point to live calmly. Another concern is that it is OK to look for contemporary references on the Internet, but we have to look for inspiration elsewhere. “Otherwise, everything is at risk of copying the copy.”

Apirilaren 24an, ETB1ean, jendeak aspalditik eskatzen zuen programa eredu bat estreinatuko da: Linbo, late night formatuko ordubete inguruko saioa, gazteek eta gazteentzat egina.