Film to narrate the trauma of a people

- The town of Bizkarsoro is not on any map, but it is easily identifiable. We could locate it in the Northern Basque Country, in the interior and in the rural environment, in the twentieth century. It is a Basque people who have hardly experienced the passing of people and the great disorder of the population. During the First World War he will have to fight first on the French side and after suffering the Nazi invasion. In short, it will be forced to give up identity and language. His death is scheduled, is in danger and will be attacked with good thought, but, contrary to all forecasts, he maintains it. And he knows, in case of death, he's going to die leaving tests for the autopsy.

Anyone who has seen the film Novecento by Bernardo Bertolucci will feel like Bizkarsoro by Josu Martínez, although the great Italian film has more fiction than Bizkaroso. A film that has drunk a lot of reality is the one that the billiard filmmaker who has been in Baigorri for years has calmly and patiently studied. It makes a passionate defense of fiction. “Harkaitz Cano says: ‘The only difference between fiction and reality is that fiction has to be consistent.’ We have invented a fictional people, although we have generally recorded it with Baigorri and the Baigorrians. The people of Bizkarsoro give us freedom. However, all stories are documented stories, we haven't invented anything. They are stories collected from written texts or oral testimonies, from here and from other regions”.

Bizkarsoro tells the history of the Basques of the twentieth century. It will premiere on September 27 at the San Sebastian Film Festival, in the Zinemira section at the Main Theatre. It will be projected in the coming days.

.JPG)

The Bizkarsoro project, which started five years ago, has received many names and has come to an end. Little by little, every year, part of the film has been made and offered there and here – maybe some others, for example, at the EHZ festival, can see part of the film in reverse. They recorded the first part, five years ago, spent the day and a half; the last one, which they recorded last year, was done in five days.

The film consists of five parts that distinguish five times lived by Bizkarsoro: In the period 1914 to 1982, the contexts, antecedents and successors of the First and Second World War; persecutions, prohibitions, signs and humiliations of Euskera and Basque culture. All of them will be reflected in the film, an endless number of stories that have been interpreted by over 200 citizens – “in the final credits, in case we have put three points” – emphasizing that the vast majority of actors are inexperienced in theatre and cinema.

.jpg)

“I remember the people in the town celebrations, thinking “this can be the character”, etc.,” says director Martínez. The mobilisation of so many citizens for a film has enriched the culture of auzolan, so deeply rooted in Baigorri, and so do the participants in the film, who have created something similar to what usually appears on Navarra Day with the work of the film. In addition to the work in auzolan, the “good reception” that the people have made to the professionals of the film has been highlighted: they have brought technicians from outside, stayed in the homes of the people’s neighbors, and the neighbors who were around the film have prepared many meals for the whole team. “The process has gone very well,” they stress.

In addition, non-professional people have taken an important step in the formation of people from the point of view of film, theatre and art, as is the case of Aña Errotabehere: “I was told that people were still needed at the time of recording the first short. I liked it a lot and I made knowledge and I learned a lot with Izaskun Urkijo.” Errotabehere is an art student who has never been put into practice this way.

The case of Lea Campistron is also significant. What he represents can be perceived as a central character (five times, intertwined but separated in time, so the characters that weigh are many). Martinez commissioned him “intuitively” and accidentally discovered that Campistron had a “special connection” with his character. Because Campistron does not have the knowledge of Euskera from home, not even the character he represents, and he was doing theatre studies outside his home country, in Toulouse, Occitania, until recently. “It’s my first film, besides in Basque; I’ve seen a sense, a value, it’s a typical revolution. I decided to study Basque again and I want to work here. Art is the way to convey the message to people.”

Martinez also recalls in a very special way the role of Campistron, told him that he was around the table: “Months after making the film you sent me a message saying that you had planned to spend the summer in the Basque Country and that you wanted to reconnect with the Basque Country. That’s why it’s worth making the movie.”

And so, little by little, the film has been built in auzolan. Recorded in general in Baigorri, as well as in Arrosa and nearby neighborhoods. The film was created entirely in Basque, despite the erdaldun language of the French and German invaders, but it was born entirely in Basque. That is, the Basque has been noticed behind the camera, in front, in the scripts and in all places. “We call the Basque film in Euskera because you hear Euskera in front of the camera, but then, many times, behind the cameras they are all in Spanish. There's an Ikuska, one of those transition documentaries, by Antton Ezeiza and Koldo Izagirre, about the normalization of the Basque Country; in 1980, the Basque Country was on the radio, in the press, and I don't know where else. At the end of the film there was a painting that Bai Euskarari said in a career, and then Izagirre said: ‘And in film, how is the Basque?’ The camera heard from behind: ‘Focus well, you see the Bai Euskarari’ (focus, look well painted).”

.jpg)

The recording of

a particular scene has been special. It's in French, it could also be in Spanish, the kids are in class, and, of course, everyone knows Basque. The teacher is a Castilian speaking speaker, coming from the capital and, necessarily, by self-indication, they must speak in Spanish. Whoever speaks in Basque will be punished and appointed, will wear a necklace throughout the day and if he detects a colleague speak in Basque he will denounce it.

“Recording this scene has been a shock for the children of the Baigorri ikastola.” In them great reflections emerged, the main theme of the houses was for a long time, because all these situations knew Basque in the classroom. "At that time they were giving birth to their grandparents, but other children, in the last chapter of the film, staged the parents of some of them, imagining the birth of the ikastola." Time of celebration until the arrival of the police. The children asked the same question: Why does the police come?

"The history of the Basque Country is a history of oppression; we have to know how to convey"

In this last scene, beyond feeling close to the parents, there were more keys to reflection, as, in contexts, the parents of some insulted other parents who studied at ikastola. This has given children and adults an idea. “This dialectic has been very powerful between character and actor in all areas.”

The past of many families coincides at several points. What has happened in many cases is that grandparents and grandmothers are Euskaldunes and love the Basque, perhaps without going to study in Spanish, but that they decided to teach their children only French, in the belief that they would “rise socially”. And it also has to do with gender: parents who taught girls French and boys Basque. These situations are shown in the film.

Euskera, do politics?

We have been quoted in the bar of the plaza de la Rosa. After many years of closure, the Errotabehere family has renewed its appearance and the bar building has been the site of the film. It is an emblematic place, which has maintained its values both in fiction and in reality; although it seems a detail, it should be mentioned that the letter is in Basque and the words of the posters on the walls are also in Basque. But it doesn't like everybody. In the Errotabehere hostel there are citizens who do not go "thinking they are not welcome". They say that a young couple who has stayed in the town of Larzabal has something similar happened and Martínez has made the following point: “This shows that the struggle is not over. People believe that speaking in Basque is politics.”

“I believe that today we live on many faces of discrimination,” said actor Manex Fuchs, one of the few professionals in the film. "Change the mask, we put more democratic faces, but actually that oppression that's told in the movie is there, what changes is the face. Sometimes it is more active and sometimes more passive is harassment.” Molds have blurred.

Is there awareness?

The film will serve for the transmission of history, historical persecution and resistance of the Basque Country, but the interviewees say that transmission is not an objective, but a conclusion. However, they consider that in the twentieth century the Basque country was "more aware" by the Franco dictatorship in the South. "Here in Iparralde, it was to be in favor of the Basque people against oppression." Regarding knowledge and transmission, they talk about a "cut".

"Rarely is it said that this story is basically a trauma," Fuchs stresses. A historic trauma, the trauma of a people. "Personal trauma is investigated, doctors are there, but collective trauma is very difficult to investigate." He returns to the film and makes the following references: the first generation that appears, that was a child in the First World War, that only knew Euskera and that has been denied the Basque, is the one that has suffered the trauma; and in the next generation comes the "division", because part has continued to deny being Euskaldun and others have resisted. There is a third generation, the next one, who has lost the Basque language and feels "embarrassed" for that, who suffers trauma. Or Euskera knows, but "maybe not so well," and he fears making mistakes, shyly. And that's what the movie says, according to Fuchs: "How can we continue to be that country's trauma?"

The film Bizkaroso aims to perform the function of memory exercise, as it is indicated that memory and transmission have been interrupted during several moments of the twentieth century. It is evident in the film, for example, when a generation has a desire to revitalize the Basque country and its parents express their intention to reduce it, since they were the ones who had fought before. The children have no indication that their parents know Basque.

"The history of the Basque Country is a history of oppression, which we must know how to convey," says director Martínez. "Maybe if we get close to it and fiction can perfectly help that, maybe more people understand why it deserves to be Basque."

.jpg)

Alosia

Perlata

Autoproduction, 2024

----------------------------------------------------

The Arrasate Perlata group has published a new work. He has several records behind him and his latest work is punk, Oi! And it was a documentary in tribute to the unrepeatable... [+]

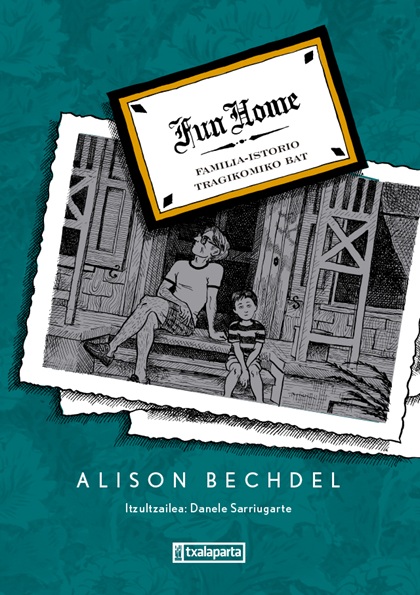

Fun Home. A tragic family

history Alison Bechdel

Txalaparta, 2024

---------------------------------------------

Fun Home. Alison Bechdel is known for the first publication of the graphic novel A Tragic Family Story (2006), although he himself participated in several... [+]

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

As the fall ends, the crows appear on Basque Day, in the Basque era or in the Durango Fair. Aware of the results of socio-linguistic surveys on the use of Euskera, the "politically corrective" exercise has no longer drawn anyone's attention. Without Ttattarri, with cool and smiling... [+]

When we woke up, culturally and administratively, the landscape showed a three-speed disaster.

As far as culture is concerned, I had the opportunity – once again – to confirm this last November 14 at the Mint library in Ortzaize. There we met because Eñaut Etxamendi... [+]

At Christmas they leave a new book on the bedside table. About the philosophy and joy of the house, recently written by Emanuele Coccia. Coccia, an Italian philosopher, has become popular in making known our connections with plants on the road to the construction of a healthy... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)