Painting of the Other World

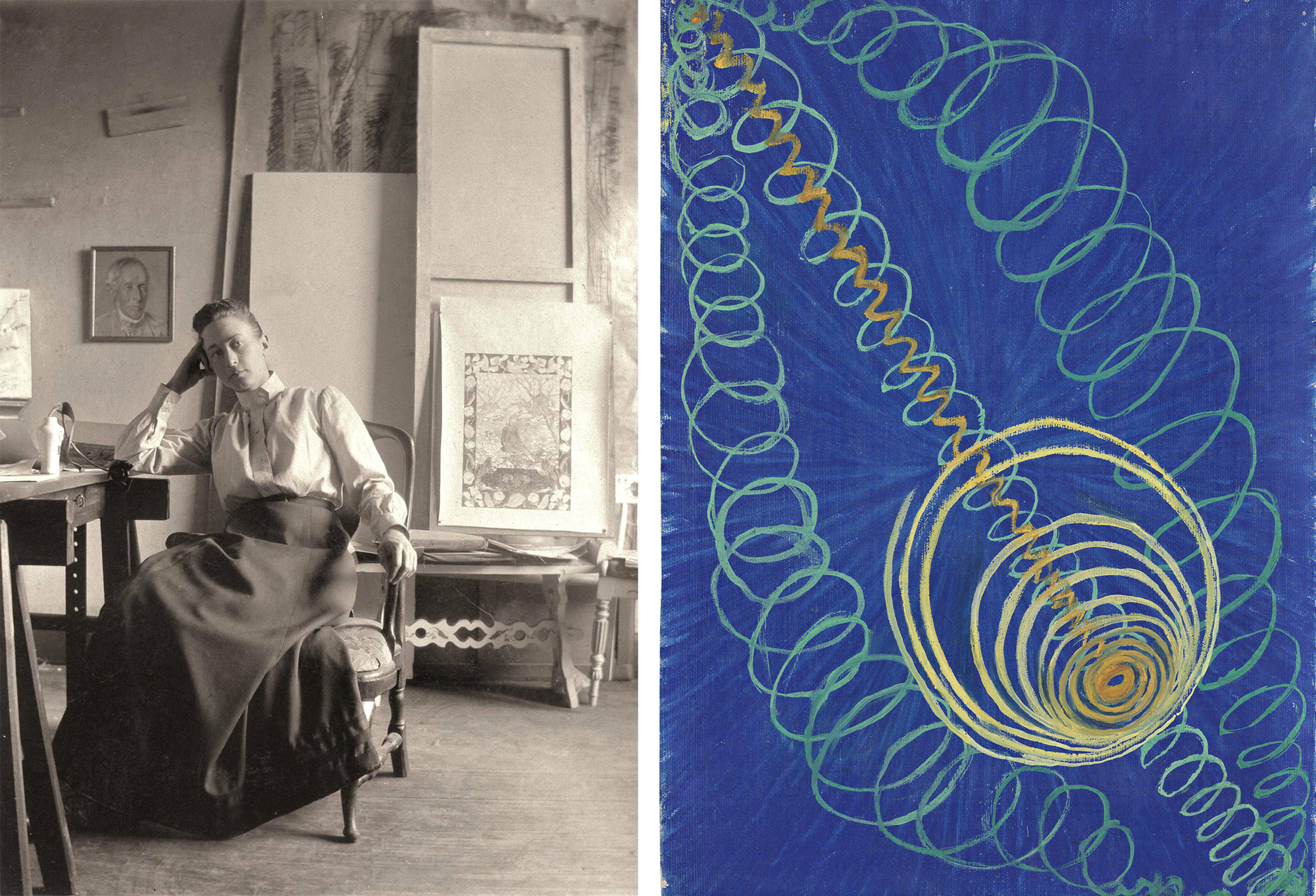

- Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (Solna, 1862 – Danderyd, 1944) today is considered an abstract painting creator, but before Vasili Kandinski his abstract work was hidden until the mid-1980s. Thousands of paintings, texts and notebooks were kept secret for two decades, on behalf of the creator himself. Thus, while painting potrets and naturalist landscapes, Hilma took the first steps of abstract painting in the dark. The purpose of this work was to shape everything that is invisible to know who we are in the cosmos. In short, Hilma's goal was to solve the mystery of life, understood as a spiritual evolution.

This abstract work highlights large-format paintings in which repeated elements appear, such as concentric, oval and expiratory circles. As for themes, metaphysical aspects predominate: the cosmos as a whole, the birth of the world and dualities (matter and spirit; female and male). Circular and spiral shapes symbolize human evolution, while yellow and blue symbolize man and woman. Symbols are accesses to other dimensions.

Hilma, who always wore his black paintings, painted under the orders of the great entities of the world. To do so, she worked as a medium in spiritism programs with other female artists. In these spiritist meetings, surrealists experimented with the most frequent techniques of writing and auto-drawing. When her 10-year-old little sister died, she awakened her fondness for the hidden sciences. Thus, in addition to meeting enthusiastic people of the Spiritist tradition, he participated in spiritual groups such as Theosofia, Rosekreutz and Anthroposofia.

According to the basic teaching of theosophical association, all religions have a “common truth” that is at the essence of each religion. Hilma also pursued this common truth, combining painting and spirituality. In the painter’s words, “life becomes farce if it does not serve the truth.”

.jpg)

Hilma died in 1944 from a car accident. But before he “noticed” his death, he dreamed for several nights of the accident: a car accident on a forest road, while a black spot covered his gaze and his hand slipped from the silver car wheel. In 2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the death of the Swedish painter.

“Bostak” Hilma

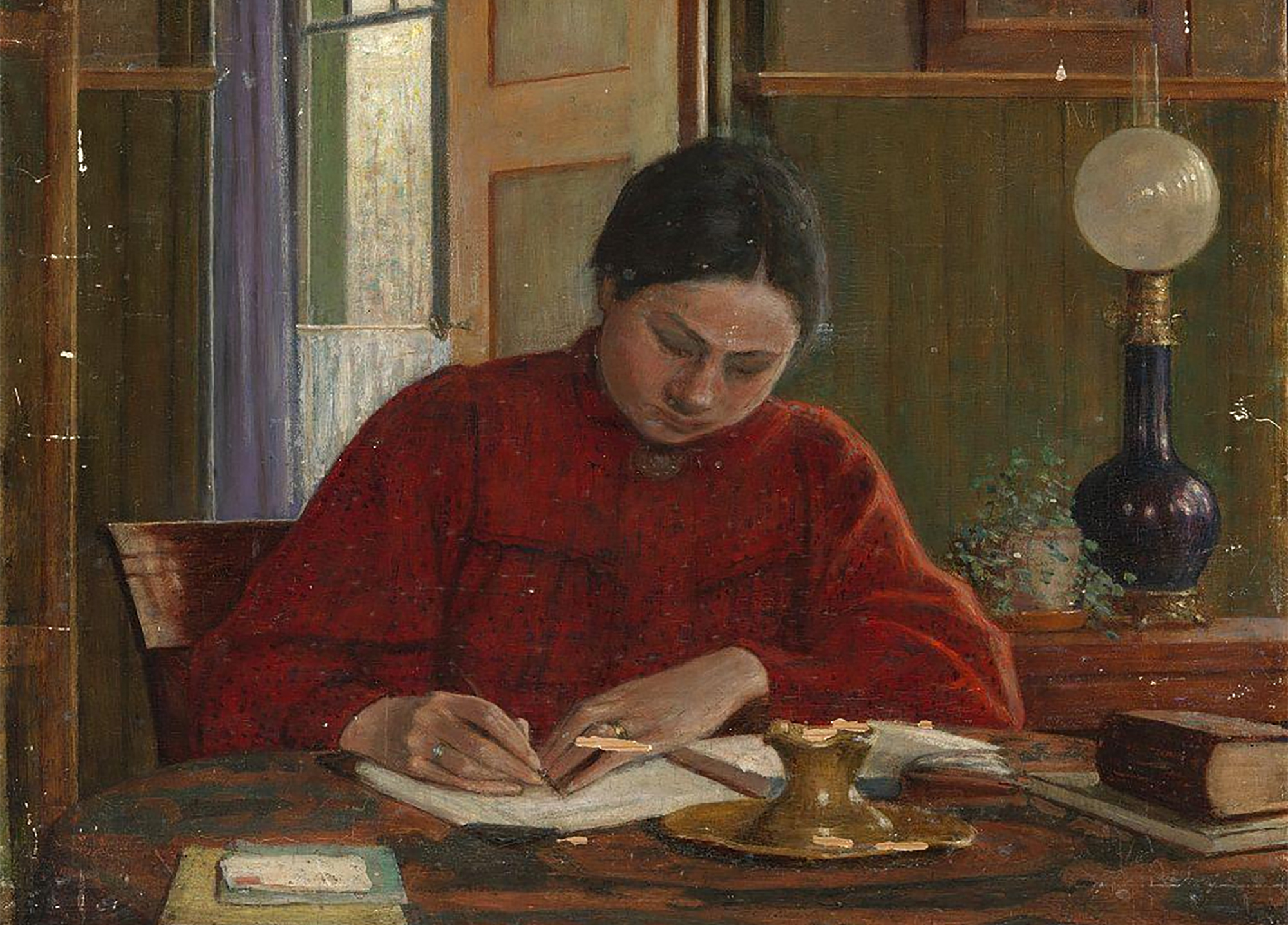

began painting from a young age, especially landscapes, fascinated by nature. Aware of her daughter’s passion for art, her parents sent her to the Stockholm Polytechnic School. A year later, her young sister died of the flu, so she was flourished with curiosity about the spiritism that was then in the bogie. He also began to read passionately the texts of one of the founders of the Madame Blatavsky Theosophical Association and to participate in the Stockholm Theosophical Society.

With the intention of continuing his artistic career, in 1882 he studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where he met another artist who would be fundamental in his career: Anna Cassel. After completing the studies, Anna and Hilma decided to transfer their artistic and spiritual concerns to another level. Thus, in 1887, they founded the De Fem group (“Bostak”) together with three other female artists: Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Herman and Mathilda Kilsson.

The group met every Friday to “contact spiritual beings of the other world.” In these sessions, they experimented with automatic drawing and writing. Well, the annotations and drafts caused by these automatisms were fundamental in Hilma’s artistic work, which translated the hidden messages into paintings.

These messages were sent by the highest spiritual entities and also received in their pleadings the names of those beings from the other world: Clement, Gregor, Ananandas, Amaliel and Amalius. The teachers' message was clear: they had to keep the drawings they created in the sessions. “(…) Our paintings are heterogeneous wavy paintings that we must preserve because they await the eyes and ears of those who will one day be able to learn a good gig.”

Spiritual art lasted

until 1907, and his notes, drawings and texts were essential to carry out the abstract work of Hilma, which painted through the automatisms learned in these spiritist programs as a medium painter. According to the artist, “the works of this time were of me, without previous drawings.”

The most outstanding work of this time is the painting of the Temple (1906), dedicated to the Tables directed to its guide Amaliel, composed of 193 paintings. According to Hilma, he worked as medium in this work, at the orders of Master Amaliel, who spoke to him from above. It is a monumental, innovative and exceptional work that he catalogued in series and groups. Topics such as the development and appearance of the material world, the genesis of matter from the spirit, the stages of human evolution, the duality of matter and human beings, etc.

This gigantic work was kept secret by the artist. Thus, one of the few who saw paintings for divinity was Rudolf Steiner, founder of the Norwegian Theosophical Society, in 1920, when his mother Hilmari died. Steiner had a great influence on the creator and asked him to keep the paintings for 50 years, as the world was not prepared to see those works, which ended up being only 20 years. At the same time, he questioned Hilma's medium capacity and caused the artist to sink into depression. It remained unpainted for a decade.

Hilma did not marry and had no children. He died in 1944, at the age of 82. His nephew Erik af Klint was the one who received the legacy of 1,000 frames and 100 notebooks. He fulfilled Izeko's instructions and kept all his work in a shed for 20 years, until he released it in 1986, through an exhibition at the Los Angeles Art Museum (USA), The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 ("Spirituality in art: abstract painting 1890-1985").

Hilma af Klint represented, along with Catalan Josefá Tolrà, the Americans Marjorie Cameron and the British Madge Gill, the tradition of medical painters who have passed the twentieth century. These women took advantage of spirituality to realize their art, but they also made it a dignified attitude to face their lives.

Bussum (Netherlands), 15 November 1891. Johanna Bonger (1862-1925) wrote in his journal: “For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on earth. It was a long and wonderful dream, the most beautiful one I could dream of. And then came this terrible suffering.” She wrote... [+]