“A very close world is the one gathered in the Bar Gloria”

- Rakel, Ana and Miguel are the children of families newly settled in a Gipuzkoan industrial village that leave their residence to achieve a better economic situation. The family of Rakel and Ana replaces the life of the house with that of their bar, and they decide to welcome Miguel, a son of family from Soria, in need of financial income, to help in his business. Nerea Ibarzabal in her first novel, Bar Gloria (Susa, 2022), reproduces the story from the eyes of three young people who spend most of the time behind the bar and in the kitchen. Markina-xemein has shown that he is capable of working with mastery not only in Bertsolarism, but also in the literature. Although we met at sunset in January, the cold and rain have not challenged us to speak of the book.

As soon as I knew I was going to publish the book, I addressed you, but you had to wait for the quotes because you had something else in your hands. Bertsolaris National Championship, no more and no less. You've reached the end. How are you?

The Championship has gone long. It was no bad thing that I separated the book edition from the later stage, the championship one. I wanted to focus entirely on the tournament, and fortunately I've come to the end. After spending fall in a whirlwind of excitement, I'm slowly landing and approaching the abandoned book in summer. Now I'm learning to talk about the book.

What was the reunion with the Bar Gloria after the distance?

I do not think I am very aware of the creations that have already been completed. I don't really know what to say, because I've already tried to say a lot of things in the book. I want to participate in reading groups, to learn to talk about literature and to gather people’s views on the book. Because you have intentions with history, and in those spaces you can demonstrate that some intentions have worked, others have not, and see that the reader has read some things differently.

I think when we go from bertsos and go onstage we have everything to do, you have to convince people one afternoon. But the literature is different: you've written what you have to write and then you go to the readers' groups. Everything is sold. In this respect, therefore, I am more than willing to gather opinions.

Do you expect feedback?

Yes. Throughout the fall I have been sent messages and emails from people nearby, I know who has read and who liked the book. Although in those cases it happens that those who do not like it do not tell them anything…, well, it is not that a goal is everyone’s taste. Readers have already been convinced of what to convince or otherwise.

People have told me everything. I've been asked why I've set myself in the 1980s, in a time that's not mine. In addition, many did not put me in the world that is pictured in the book, in that particular landscape, in bars, in oxen tests, etc. Some people are curious about where I've come from, and I tell everyone that it's a world that I'm very close to, that these are types of characters that I'm very close to and that I wanted to write about all of that. I felt his wounds were mine in many ways, and I had to write about it. And although I'm not the one who lived that particular decade, I think that in part the decade or the temporary ambition is not entirely meaningful, or at least for me it has not been writing. I felt the pains and joys in the book as the pains and joys of any other decade, and I wanted to focus on them, not so much at the time. I didn't want to make a historical novel.

From my side, I believe that you have entered the world of Basque literature through a great door. I found the novel very good. How do you feel?

I've stayed at ease. I think that is what I can do in the time I have had and that in the end it has approached the story I had in mind. I have also been very afraid, because I did not know very well where I was going, and in this sense the presence of Editor Leire López de Susa has been a great support and lesson. At the last minute, when you have everything prepared and you have doubts, it is very much appreciated that someone like Lopez will accompany you. When he says, "He goes to the printing press," and when you start thinking, "Wait, I just want to change everything," it's beautiful what he says to be someone next to you: "I have confidence in this."

And the creation process, how has it been?

I got a government scholarship, and I had a one-year deadline for presenting a sample of the novel. The thing is, the scholarship didn't commit me to publishing anything, and I was writing for a year, thinking I was never going to publish what I was writing. That has given me great peace of mind, I think it is an aspect that has greatly influenced the creation process. I believe that the book shows its influence, there are indications of that year dedicated to observation and information collection. It's like I've been losing the ingredients of a perfume. I realized it had a scent, and then I wondered, "What now?" I would like to refer to those who at the time convinced me to publish the book, because it was achieved by Uxue Alberdi, Miren Amuriza and other creators in the area. In these cases personal insecurity is involved.

We started with the title. The characters in the story are not exactly glorious. I think irony is an intentional quest.

It was clear that the bar was going to be called a woman. Moreover, when a name comes behind “Bar”, in this case “Bar Gloria”, I think we all have a concrete bar model. It takes us to a place. And why Gloria? Well, as you said, to give rise to the paradox. Because the characters clearly have a struggle to approach that unattainable glory. They want purpurpurine and euphoria and mismatch, but they are necessarily mixed with sawdust [the one they use to clean the ground from the bar].

"I think the starting point of everything was a question: how is it possible that people who have spent their entire lives working end up being poor? Get to retirement and have nothing?"

He said that history was in the 1980s, but the book did not explain at any time the time we were in. You put the reader at this time through descriptions. You can see the documentation work behind it.

I have resorted to photos, movies, books... but I have based on interviews with many people in the area who have been mainly the hospitality companies. And when I had doubts, I asked. In this sense, throughout the time that the book has been produced there has been feedback, partly because I wanted the story to be as credible as possible, and because I feared I would not achieve it. I wanted to gain credibility, but not for nostalgia, because those who do not live the time do not. It was more the challenge that I posed “to see if I’m a capaza to catch that scene” and curiosity. For example, I don't know what the Green Cow drink looks like, I've never tried it, but it's quoted in the book, and to make it credible as I wanted, I describe it. Perhaps I have even too often described some issues I do not know. Because if I wrote about drinks in 2010, I guess I wouldn't focus so much on descriptions.

I'm very grateful to those who have been willing to tell their experiences, because once I've started to ask, I've realized that people have had a lot of things uncounted. Especially situations of violence and events in bars. And they've gone on with life until nobody asks them without knowing what things can happen in a bar, nor what to say has to have spent their whole life. In this sense, it has been violent.

He said that the accounts that count in the book, people, touch you very closely. Where is the Bar Gloria born from? What was the spark that led him to write the novel?

I think the starting point of everything was a question: how is it possible that people who have spent their entire lives working end up being poor? Get to retirement and have nothing? I saw that reality all around me as a pattern that was repeated, and many were people going through the bar, especially women. I understand why that happens, I understand the structure of this system, but I wanted to focus on a family that has a bar. Through my experiences I wanted to gather how a family of this kind manages a concrete situation – either bad or well –, how can management be in the economic sphere, but also in the personnel… And if all this is so, nothing guarantees you tomorrow. What I wanted was more to receive that pain, that emotional pain. Once you've started writing, you can't find answers, you even multiply the questions.

On the other hand, although he wanted to contextualize several people from the area in their youth, he did not want to locate them only in the bar area. I didn't want to limit myself to the time span of the bar, and that's why I've zoomed a little bit sometimes, whether it's adulthood or childhood. At an adult and child age without bar. So I've been able to add layers to the characters.

.jpg)

The story also depends on where the story is told and is closely related to the question from which the book departed. Most events are narrated from the bar, the need to end the month keeps the protagonists most of the time. It seems to me that it is a story about the conditioning that forces us to work, a class condition.

Yeah, that's right, imagine that class I wanted. Work becomes prison when you can't leave it, when you need money. In short, to escape from a place, for freedom, you need money. And the book presents two families in this situation: the two working-class, one more privileged than the other in certain aspects, and the relationship between them is built through work. I wanted to pick up the people who have joined the jobs and whether the relationships built through work are special and alive, but also fragile. Because it's something I've seen many times: the person who works with you can go from being an important part of your life to being someone who disappears from your life, hence I don't know how many years without knowing anything about it. Work has a special complement when describing relationships.

The silences, the disseminated and the unspoken are important in the novel. "I've tried to unpack that language from people who don't speak clearly," I read in an interview. It is curious: a bertsolari and journalist like you, who has the word as a strong point, (of course) observing what has not been said. Why want to put the spotlight there?

Although I'm a person who's very related to the word, I think I'm also a person who calms more than he says. In my environment I have learned to manage many situations without speaking, to move forward without solving the knots. For many people I know, the thoughts speak loudly, but the mouth doesn't. I think that is the type of language that predominates in many families. And who benefits? Well, they've usually just silenced conflicts, and that's what harms the usual ones.

And if we extrapolate to the bar what happens in the family institution, the same thing: in a situation of violence between the four walls of the bar, silence protects those who are always. In addition, there is a mixture between public and private spaces, mediating among them “the client is always right”. In this context, I've also wanted to look at the way people talk through their eyes, in body language, in that narrative in a different way.

"The person who works with you can go from being an important part of your life to being someone who disappears from your life. Work has a special complement in describing relationships"

In general, I find it very difficult to build credible conversations. What I write seems to me to be a puppy, I think a Goenkale dialogue [laughing]. I read and thought, "What is a FP theater or -- a book? I don't think this!" Maybe I don't know how to write conversations properly, and that's why I've finished writing a book about silences.

When it comes to building the silent characters, like the father of Patxi [Ana and Rakel], that model of man and man, I've tried to remember to rebuke, threaten, or essentially silence, both the people around me and the people who spoke in Basque.

It talks about situations of violence and silence before them. The reader will forgive me, but a violation opens the book. For page 15, the reader has been placed in a context that can become hostile in the middle of a second. And this hostility is usually the result of the power exercised by men.

I was interested that in spaces massively dominated by heterogeneous men, survival and alliances of other identities would be regained. For example, the character who suffers the rape, Miguel, was clearly going to be marica. In addition to what I mentioned, because I also wanted to reflect some spaces of the LGTB movement of that time.

You have focused on the public space in which male domination is reflected, on the monopoly of men.

Yes, especially in bars, in rural areas and in rural sports, specifically in stone trawling tests. I've incorporated tests of oxen because it's a world that I've lived through very closely, but I also think it has a peculiarity: the animal factor comes in, and that allows animals to also become characters and speak from their human eyes. I've suffered a lot from the use of animals in rural sports, and when I wrote the book, I was interested in collecting that world by making the animals themselves characters as well.

"I was interested in receiving in spaces massively dominated by heterogeneous men the survival and alliances of other identities"

Doing so also allows us to see how some men are accustomed to the clientele and instrumentalization of animals. “I’ve paid money for you, so you’re going to do what I say, you’re going to go where I say.” And from there, their logic is that they can act like this with all the people around them. “My wife, my daughters … will pass where I say.” And this is the basis of relationships of service or slavery.

Coupled with oxen tests, I was more interested in the oxen cottage than the plaza. Because I believe that there is a new relationship with nature, and as a result you can detect things that are not seen in the square: other men, who are allowed to demonstrate tenderness, who love animals… always with a specific objective.

The family carrying the Bar Gloria had to leave the house and go to the industrial city. The family of Miguel, who works in the bar, has left Soria behind to seek in the Basque Country the work they lack there. It's also a history of uprooting.

It's not something I've lived through in my narrative, but I think it's something that leaves a very hard impact, especially when it goes hand in hand with the prey of adaptation. And there's almost always that rush, because normally the cause of uprooting is the desire to live in better economic conditions, a better life. And in that process, how many things and emotions people hide in themselves… The town/city dichotomy that is done in the book may have made that rural childhood environment very bucolic, but the people that I have really interviewed so have told me. And this highlights the impact that landscape change can have on individuals, and how hard it can be to adapt to the city for the child who has never seen factories. I think the loss of relationship with nature is very hard, or at least I live it.

Bizenta, the mother of the family, can pass as a secondary character. However, it seemed to me that Bar is not only the axis of Glory, but also that of history.

Both Bizenta and Patxi are both father and mother, playing these roles fully. And clearly, when Bizenta is missing, the bar disappears. Bizenta embodies the “absolute mother” model that has been worked a lot in Euskal Herria, and wanted to see how much harm it can cause in some moments. Because she is a mother fleeing conflict, trying to support everything from another place, behind and in secret. And so you can't keep a lot of things going, and eventually you get sick and you die, either symbolically or literally.

I wanted to use that mother model as a warning. Once dead, Bizenta does not rot in the story and there is the warning: “I am here”. And what draws attention is not precisely “I am a saint and I am the model woman you should follow”. Moreover, “Live and run from where you are going to run. Because it’s also not good that they don’t rot after fifteen years in the coffin like me.” The warning is mainly addressed to the eldest daughter, Ana, as she is a woman who returns to the bar after leaving home. The role that Bizenta embodies is the one that wanted to question more than to idolize.

You tell me that those in the book touch you closely. Therefore, the book has also forced him to explore what touches him. How did you get out of there?

I feel better. I feel like I asked something I had to ask and I got an answer, and I noticed that I created some pain. I feel that I have taken a look and that a lot of people who have spent their whole lives working have been acknowledged.

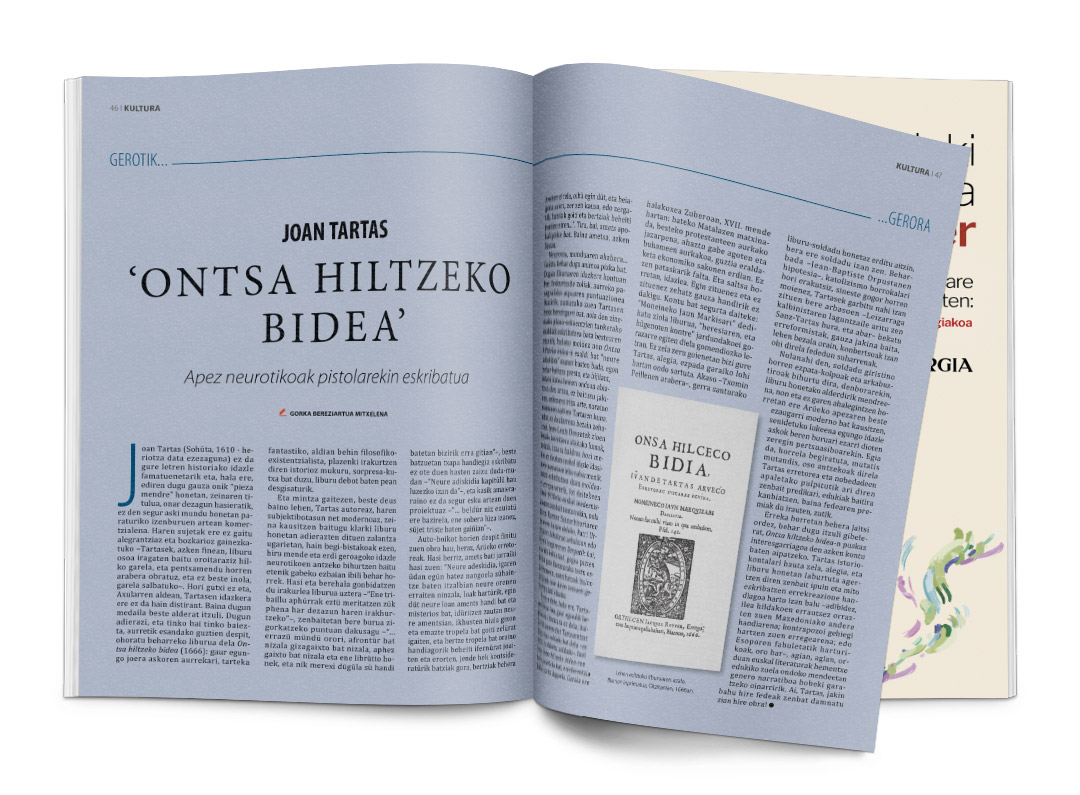

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)