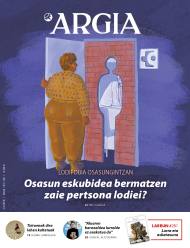

Infinite universality

- Art, through its poetic and symbolic language, has this ability to point out and testify to reality, situations and facts. In particular, contemporary art offers us other perspectives to address the reality around us, which can be more veiled and sensitive; and through the images, artifacts and objects it generates, it offers us access to reflect on the world we live, although sometimes these accesses are narrow and coded. You have to be alert to the signs. In this contemporary cultural landscape is the work of Kimia Kamvari, in which, through a poetic and simple imaginary, his work brings us closer to the consequences of current climate change or to Iranian battles, deepening into an apparently fragile but firm work.

Kimia Kamvari (Cologne, Germany, 1986) is an Iranian artist currently living in the Astigarreta district of Beasain. A few years ago, Tehran’s frenzied life was altered by a more peaceful life in Astigarraga, two sites that pass through its artistic practice. Since 2015 he has lived in this rural district of Beasain and the nature around him has become the main engine of his artistic practice and his main work tool. The materials he draws, paints and portrays – trees, plants, corners, birds – are found in the margins where he lives, and the materials he uses to portray that nature are often pigments, dyes, charcoal wedges or plant papers derived from the same nature. There is therefore honesty and reciprocity between what it does and that way of doing. And that is already a strong statement.

At the San Telmo Museum in San Sebastian, within the Artea Abian program, an individual exhibition entitled Alef has just opened. From the title, the exhibition has its own suggestive universe: Aleph, the first consonant of the Hebrew alphabet, is a principle of life, an energy that encompasses all possibilities. Álef is also the first letter of the Persian alphabet, a symbol used in mathematics to represent the cardinality of infinite numbers. However, the concept of Aleph of the best known is made by the story of Borges. In the book of the Argentine writer El Aleph, Aleph is the mythical point of the universe, where all actions and all times (present, past and future) meet the same point, without overlaps or transparency. It follows that Aleph, as in mathematics, is infinite and therefore represents the universe. In this critical, fragmented and almost apocalyptic situation that we live today, it seems that talking about these infinite universalities opens our horizons and doors to hope, if only to inspire.

The exhibition is exhibited in the Museum Laboratory and although the space is complicated – surface in an irregular way, ceiling of two heights, wooden floor with great presence – the space is solved in an incomparable way. It takes the panels out of the walls and turns them into a compact, rectangular, elongated architectural structure, dividing the central space diagonally. The artist has used the two sides of the long element to present the two central works that make up the exhibition Alef: Burning Willow (Zumea sutan, 2022) and Negative Landscape (Negative Landscape, 2019-2022). The latter is a installation of 73 photographs printed in black and white. The photographs cover almost entirely the surface of the wall and all of them show an arid landscape, which could be called desert, but it is not, with sinuous and curved forms of an irregular orography. If you look closely at these landscapes, there's a repetitive element: big holes that swallow land and grow inward. Then I've known that in geology these geological accidents in nature are known as dolinas. At the bottom of the photos are written the coordinates of these dolines, and following these coordinates, I've known that these arid landscapes are from Abarkuh, Kane Zenian and Shira, on the southern plateau of Iran.

.jpg)

Dolines are geological situations that occur in dry places due to atmospheric drought; a doline, such as karstic formation, is produced by dissolution of the rock or by falling the roof of a cave, giving rise to depressions in a circular and different size. They are also the result of human intervention in nature, diversion of river waters or the construction of underground mines. Kamvari began in 2019 with a stenopic chamber portraying these holes in the Iranian plain, representing those holes and crater forms that could be negative for mountains and hills, placing a focus on those wounds that spread across the ground. In the tradition of art, emptiness, lack of materiality or these negative forms of material have been as important as materials, and especially in sculpture, it has been a subject of great tradition. In 2019, the artist showed twenty photographs of this series in his individual exhibition at the Tehran Gallery Tasting under the title Event Horizont. Over these four years the photographic series has been expanding, just as these dolines have done in nature.

He has also brought to the Kamvarik room a letter from the philosopher Aidin Keikhaee, in which he states that these dolines are yet another consequence of climate change. As is happening with other pests such as COVID-19, an increasingly violent impact of climate catastrophes, suggests that it is a consequence of geopolitics, which also has different effects and consequences between the Southern and Northern Hemispheres, being the harmed always those who live at the bottom of the globe. In the Hamadan area, 400 kilometres from the capital of Tehran, fertile areas until recently destined for livestock and agriculture are in the process of desertification, which means that there is less and less chance of dignified living. As soon as it rains, water is a precious and scarce asset in recent times, so the earth has begun to spread inland and in this leap devours the possibilities of life.

In Burning Willow we find dozens of drawings made with charcoal sticks in which the same type of bush appears drawn on white paper: the weeping wicker. It's a well-known tree in our landscape, but it actually has its origin in Mesopotamia. There comes the adjective of the weeping because its branches lean towards the earth, in tortuous and almost impossible ways to bend, in search of the moisture of the earth, also of water, in search of the principle of life. These trees are abundant in our surroundings, because with the mimbres extracted from the branches they could make baskets and baskets, and their wood was used as fuel to warm the caserades. The carbon wedge, the pencil used for drawing, and in this case the organic pencil used by Kamvari for all drawings have been extracted from Zume's wood. At the height of the drawing installation we find a black summit, a set of coal wedge dust from a tear. Wicker is a water-thirsty tree that the artist has portrayed us in different ways.

In September 2022, police violently killed student Mahsa Amini because she wasn't wearing the hijaba well. This fact launched the protests that are continuing today, in which thousands of students and citizens are fighting for the human rights of women. Kamvari has chosen one of the images he saw on social media during those fall days and made a nice drawing: a group of students protesting against the Islamic Republic of Iran. Behind there is a weeping wicker. Also, fighting for life, thirsting for freedom.

Behin batean, gazterik, gidoi nagusia betetzea egokitu zitzaion. Elbira Zipitriaren ikasle izanak, ikastolen mugimendu berriarekin bat egin zuen. Irakasle izan zen artisau baino lehen. Gero, eskulturgile. Egun, musika jotzen du, bere gogoz eta bere buruarentzat. Eta beti, eta 35... [+]

This text comes two years later, but the calamities of drunks are like this. A surprising surprise happened in San Fermín Txikito: I met Maite Ciganda Azcarate, an art restorer and friend of a friend. That night he told me that he had been arranging two figures that could be... [+]

On Monday afternoon, I had already planned two documentaries carried out in the Basque Country. I am not particularly fond of documentaries, but Zinemaldia is often a good opportunity to set aside habits and traditions. I decided on the Pello Gutierrez Peñalba Replica a week... [+]