Meeting our needs

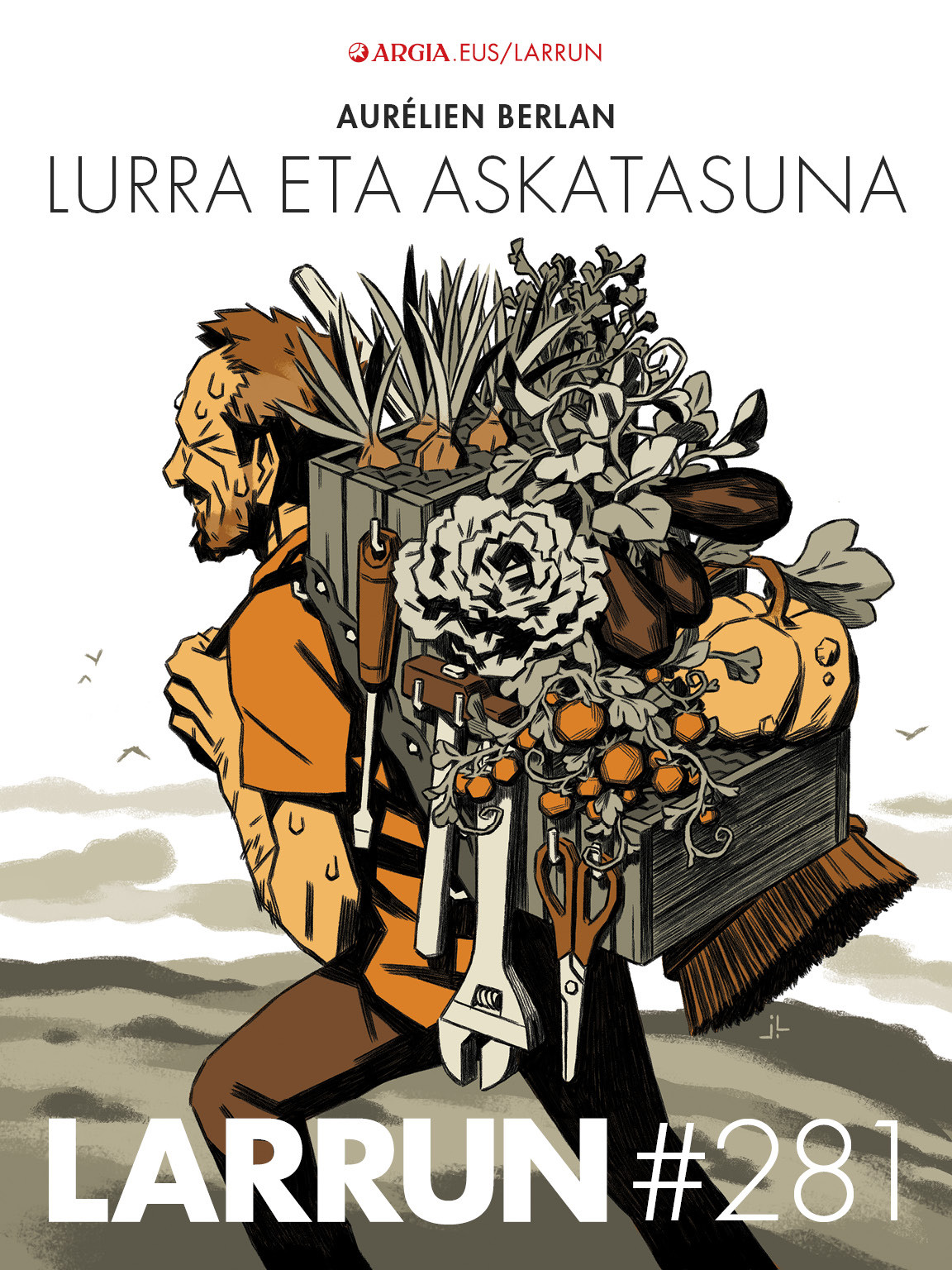

- Aurélien Berlan, philosopher and horticulturist, writes and teaches for half a time and dedicates the other half to ‘survival work’, as in the garden at home. In November 2021 he published in the small editorial La Lenteur Terre et Liberté, the quête d’autonomie contre le fantasme de livrance (La Tierra y la Libertad), which is being very mentioned and praised in the francophone world of political ecology. Desire for autonomy versus nightmares of dispossession). Among the various presentations made by the author and the interviews he has offered, we have selected for the readers of LARRUN the talk offered by Radio Zinzine in the coffee library Michèle Firk of the city of Montreuil, municipality of metropolitan Paris, with 111111,000 inhabitants. What is the relationship between the socio-ecological situation and the modern conception of freedom? Why can the ecological crisis not be understood globally if it is not the social crisis, exploitation and domination of human beings? On what philosophical and political supports are the efforts to acquire material and political autonomy, which we can find at the center of various emblematic movements against political ecology and global capitalism? Aurélien Berlan demonstrates that modern concepts of freedom, whether liberal or Marxist, have within them a desire to get rid of tasks, with profound social and ecological consequences. This vision has been imposed on another conception of freedom that we see resurrected in these times: autonomy understood as assuming our life. According to Berlan and the thought he represents, if we want survival to be both land and freedom, we must delve into the line of that other imaginary. Aurelien Berlan lives in Saint Sulpice la Pointe, near Toulouse, on a collective farm.

I'm very happy to introduce this book here in Montreuil. Let’s say that in my “previous life” for ten years I wrote a doctoral thesis, published part of it under the title La fabrique des derniers hommes (The Last Men’s Factory). It was a university issue, very academic; I explained to several authors to explore in different questions about the world we live in today, trying to understand what is wrong with this industrial capitalist world. And with the completion of the thesis, in 2008 I became famous for the city and moved to the rural area, to the Tarn region: the day after the doctoral dissertation was delivered, we took a truck with a group of friends and moved to the countryside looking for a home. I live there for the last twelve years and I am very comfortable.

Aurélien Berlan demonstrates that modern concepts of freedom, whether liberal or Marxist, have within them a desire to banish tasks, with profound social and ecological consequences.

Why did I leave? I am very happy with you today, in Montreuil, because I lived here, in an atmosphere of self-employed, living for a while in the squatt [occupation]. In this environment we debated a lot about autonomy, what it is to live independently, what its essence is ... Political autonomy was easily understood, organized apart from the large parties and institutional structures, outside parties, unions, foundations, trying to organize us to intervene politically in the world. The second meaning of autonomy, from the beginning, is that we ourselves set our own laws, whether it be a people or a group of citizens who decide their rules when deciding on issues that are important for the future. In short, direct democracy.

In the debates between us we also devoted ourselves to another idea of autonomy, of material autonomy. We were anti-capitalist, therefore we criticized the paid life, the consumerism, the electoral system… but we saw organized life in search of autonomy, which was based on squatt (occupation), the reuse of waste found in the street, not having to sell our work to others, not being condemned to perform jobs we do not like in exchange for a casual worker… it was a nice way to live, but very short.

The length was very stressful, imagine that some people living right here in the squat got home once at four in the morning the RAID police [RAID is the elite unit of the French National Police, such as the Ertzaintza Intervention Group or the OMG of the Spanish National Police], every six months, it's not sweet. On the other hand, these kinds of experiences are possible when you're young, when you're in full shape, but you don't think about them for the most physically or psychologically vulnerable. If you stay in Paris, you will be living soon or late paying for the rent, to do this you will have to put yourself at the service of a salary, if you go into salary you will have less time to do politics and other activities, you will have to stop going to the collective gardens and go to the supermarket… to end at ten years, unfortunately, like any “monsieur X” or “madamme Z”, alienated, crushed.

.jpg)

That time was the end of alterglobalism, at that time I began to form myself, since 1980. So I realized that almost everything I consumed, all the caches I used daily, were produced in ecological and social conditions incompatible with the values I had by then.

A life that did not satisfy us, that we wanted to move away from it, and that we should free ourselves from those dependencies that we talked about in the debates that we had in Montreuil, and that in time we should develop other life models that would not once again engulfed the systems, that would have greater material autonomy, and that would be easier in the rural environment.

In 2008, I planted in Tarn, we immersed ourselves in various activities, we produced our vegetables in our own orchards, we grew small groups of cattle, we grew up in auzolan construction, we harvested wild fruits, we produced our vegetables in political activities, and so on, which is a very nice thing. At the same time, we wanted to delve into the political meanings that underpin this autonomy … because it is true that it is possible to make material autonomy efforts in an absolutely inpoliticized way. In this sense, we did not want to focus the Colibris movement over time on agroecological experiences organized around Pierre Rabhi, which also did not satisfy us.

In addition, there was a philosophical problem: autonomy can also be understood as synonymous with freedom, and it is known that the social model we criticize so much speaks of freedom as a central value. What difference does the autonomy we defended so much from the conception of freedom that reigns today? There was an analysis work, and as I kept loving philosophy, I started doing it.

The ecological disaster in which we are immersed is closely related to the distance between consumption and production, which characterizes our lives as employees.

Another thrust of the book was Snowden's theme. That's what the book begins with. As you know, in 2013 he was a member of the U.S. secret services [Edwar] Snowden published how his country had massive spy systems in place. By then he was already immersed in classical texts that have worked freedom. As you can read from them, in the so-called liberal tradition of freedom, the inviolability of private life is the ‘leit motiv’. Alta, Snowden showed that in our liberal or even ultraliberal world, so criticized by the left, they systematically used private life under their feet. It has shown that we are in an orwell-off world where the word freedom has exactly the opposite meaning, let's say. And so we come to the great present mixture, in which the only people who finally campaign around the word libertate are the right extremists, both in France, Germany and so on. Liberal regimes therefore crush freedoms and it is precisely the non-liberal and anti-liberal forces, as the media call them. It is a serious mixture.

It must be remembered that freedom, since the time it was first written, has been the symbol of the Protestant and revolutionary movements that wanted to deal with autocratic or oligarchic powers. During ancient times freedom has been linked to the revolts of slaves for debts, in Greece and Mesopotamia. It appears in ancient Rome among commoners in struggles against patricians. In the whole of the Middle Ages we find the fight against feudalism in all the peasant riots. It is at the heart of the French revolution, with the motto of the revolutionaries of 1793 being free or dying. In the late 18th century, peasants planted in all the villages “Trees of Freedom” to dance and celebrate their freedoms.

Freedom has therefore been a revolutionary demand, a call to the destruction of privileges and inequalities.

Industrial capitalism has assumed this concept since the 19th century, and today the forces of the far-right are making an OPA. the one of

There are no thousand ways to get rid of everyday tasks: you have to leave them behind someone else. Not doing things yourself, but getting them done to others, with very important social, political and ecological consequences.

This is, therefore, the context in which I have worked for ten years to clarify the cinematic salsa of freedom and autonomy. I have worked in depth because I have done higher studies, I have obtained the doctoral thesis, the habilitation to lead research in university… and, therefore, I have that aspect of the ‘Chinese student’, so I have read what philosophers, historians, anthropologists, etc. say. And then I've tried to explain to people as easily as possible, because on the one hand, the academic language that stops me, which prevents me from clarifying things, and on the other, I think we all have to. That is why I am particularly grateful for your cooperation with all those who have supervised my writing, who have warned me: “this is too long” or “it is not clear” or “set an example” or “clarify your argument”.

With regard to the meaning of freedom, one might think that although there is currently great confusion, it was very clear at the time, especially on the left. However, it must be borne in mind that it has never been very clear, that the mixture has been around for a long time. In ancient Greece, freedom was to be equal in the public square, but limiting equality to those who had citizenship, that is, to a maximum of 20% of the population, men, born in Athens, etc. Freedom was therefore the one mentioned by Orwell, dependence; it has long been demonstrated that the freedom of the Greeks was based on slavery. There is therefore no clear copy of this concept to return to it. It always has several knots that I have tried to release with this work.

In general, I have explained in the book two conceptions of freedom that cross our aspirations and aspirations and that throughout history are confronted in all texts, although not clearly explicit. On the one hand, freedom understood as “taking away tasks” in the original “delivrance”, alleviating the burdens, overcoming them…], that is, the hegemonic meaning of the concept in the modern world, especially among liberals, but also in part among Marxists. In the face of this, I have tried to demonstrate that there is a very different conception, that it has always been buried, that it is not found in philosophical texts, but rather in the background of the struggles of the popular classes and of them to liberate them, and that what has been little has been explicitly defined, that is what I call ‘autonomy’.

This is rising from its ashes, especially in that world we call political ecology and more specifically in what we call ecofeminists. These have been linked to the popular conception of freedom, in which freedom must also have material autonomy. I believe that we too at the Montreuil squatt fifteen years ago were trying to link with some evidence that was forgotten, that is, that if we are fully subject to the system to meet our material needs, the system is completely dominated and we cannot be free. The grass-roots classes have always known this, which is why they were struggling to access basic resources, something that has then been completely abandoned and that today comes back strongly in the struggle to acquire commons. The aim of the book is to help feed this background movement.

Therefore, on the one hand, freedom is understood as “task overload”. Today, the concept of freedom is often confined to its institutional aspect: democracy, the holding of certain guaranteed rights, rights of movement, expression or association, so-called public freedoms, etc., increasingly attacked by regimes that declare themselves liberal. They focus on most philosophical theories.

The popular classes have not struggled to get rid of the material obligations of every day: they have struggled to find ways to meet everyday needs and, above all, the land, the basis of every resource to survive.

But if you look more closely, freedom also has a material aspect, less mentioned. And being free in that means being free from the material obligations of every day, from many tasks necessary to survive, because we consider them annoying, boring or heavy. That is, the production of daily food, the construction of the place of residence, the cleaning of houses, boats and clothing, the care of disabled people in the area, etc. In the modern conception of freedom we can only be free if we are freed from all the needs and tasks we have to live as we live. This idea is understood by all philosophers from Plato to the present day, all the thought of the West considers it an evidence and catches us all, if not one. In my own case, when

I was making the book, I often wanted to get rid of the work of orchard or building the house, which are more than a nice obstacle.

The problem is that this widespread attempt to get rid of material works raises a number of problems. There are no thousand ways to get rid of everyday tasks: you have to leave them behind someone else. Not doing things yourself but getting them done to others, and that has very important social, political and ecological consequences. If freedom is to get rid of everyday tasks so that we can act in more receptive and pleasurable activities, then freedom is based on the mastery of others… and we are back on what we attribute to the Greeks: freedom is based on slavery. Why? The social domain formula is based on making people do themselves to meet their needs and make others do. Political dominance is based on the distinction between leaders and authors, who send others what they have to do, who do what they have to do on the other hand.

If we look at history, all the ruling groups of all time have left behind a series of everyday tasks, causing the dominated to do them: women, slaves in antiquity, servants in the Middle Ages, workers or payers in modern bourgeois times. Authoritative classes have used different strategies, very different, of different degrees of violence: those that in ancient times did not want to be forced by people, had to threaten to cut their necks, but there are softer forms, money, trade, mental domain… I will not quote all the details here, I explained them throughout the book. I am going to focus today on the ecological consequences of this gesture of making our role in the consumer society in which we live.

The different thinkers of political ecology have shown that the ecological disaster in which we are immersed is closely related to the distance between consumption and production, which characterizes our lives as employees, which in my practice would define the formula of thinker André Gorz as: on the one hand there are the salaried producers, who do not consume anything they produce, and on the other hand the consumers, who do not produce anything. There's a whole cave and other ways of life where things get brighter. This idea is at the base of the desire to build a short-circuit consumption, to do things, if possible, or to solve them ourselves, and not to do everything to others.

Autonomy is not independence, it is the struggle against asymmetric dependencies. This means building interdependencies, and this is only possible on a small scale.

Why is this distinction for the ecological problem? First of all, the gap between consumption and production has taken on a global dimension, there are centers where most of what is bought from afar is consumed, and in the peripheries, China and others, they are immersed in the production of things that are going to be consumed out. This requires, of course, complete logistics, means of transport everywhere, pollution, etc.

The other problem is that it makes it possible to take away from the consumer the ecological and social damage caused by this production. As I told you, I realized at the age of 25, thanks to the alterglobalist movement, how many farms and contaminations were behind the things that I used to consume so calm and without questions. Because this reality is invisible, because the division of labor occurs worldwide.

The last argument, and in my central opinion, is that the ecological disaster is related to the constant increase in our needs [‘fuite en avant de nos besoins’]. We increasingly need more things, ever more… we are immersed in a dynamic of continuous growth and constant needs and desires. Surely, when things have to be done by yourself, there is a certain self-limitation of needs, because when things have to be done by yourself, the first goal is not to spend all day as crazy trying to meet needs that have no limits. If you know how tired it is to do things, it’s not so easy to throw your old jeans into the trash, you think it’s no more worth fixing with a patch than making a whole new garment from start to finish. On the contrary, nobody and nothing satisfies those who do everything. The insane consumerism in which we are immersed is closely linked to this discontinuity between consumption and production.

I will mention their social and political implications. The distribution between production and consumption leads in part to the distribution between direction and execution characteristic of the social domain. But it is only true to some extent, because, although all the dominant classes are consumers, many consumers are not of that kind: I too regard myself as a wage consumer, although I work a lot of autonomy, I am also a consumer of many things. The truth is that, if at first the dominant classes were characterized by the consumption of others, by the industrialization of the world and, above all, by the expansion of mass consumption, this way of life has been “democratized”, in quotation marks, I would say more concretely that it has been generalized, made available to the masses. And then its political significance has changed radically.

In the past, overcoming the duties of survival was a mark of social superiority. But with the expansion of mass consumption, this desimposition has become the padlock of our disability. We've all become dependent on a system that we don't control at all, because if the system stays, even if the system sends out tremors, the panic would spread: "how will we live?", "how will I feed our children?", "how will I get warm?", "where do I get the garments?"… This dramatic solution that we are involved in today is at the risk of the majority of the planet.

Freedom has therefore been a revolutionary demand, a call to the destruction of privileges and inequalities. Industrial capitalism has embraced this concept since the 19th century, and today ultra-fast forces are making an OPA.

We live in a paradox associated with our material dependence. Freedom means getting rid of social oppression, but also achieving complete independence. That's why we feel powerless. We know the future that awaits us if we continue along this path, but we cannot leave, change course, stop. Because we have become dependent on this killer system, both individually and socially.

The idea of freedom, if we accept to look from another point of view, helps us understand two things. On the one hand, what is the root of our current inability to cope with the orders, system and ecological disasters of the highest. On the other hand, what profound problems do not allow us to differentiate the ecological problem from the social problem? To some extent, the ecological problem is the result of the fact that in the nineteenth century the social problem has not been solved: it has not been possible to build a more egalitarian society, different from capitalism and the need to produce and consume more and more. At the root of both is a conception of freedom based on the juice of men and nature. We will have to change them if we want to find a solution or at least stop this disaster that we are trapped in.

Saying all this is hard, but there are also clear expectations that not everything is closed. Because there is also another sense of freedom, which I have assimilated into autonomy. The other, that equation of freedom to ‘delivrance’ or to the elimination of unpleasant daily practices, which has in fact become a conception of privileged but hegemonic among liberals as among Marxists, has imposed to pressure the desires of the popular classes. In general, if we look at how the popular classes have lived and what kind of fights they have built, they did not struggle to get rid of the material obligations of each day: they struggled to get the means to meet everyday needs. The first and foremost was land, the basis of every resource for people's survival.

In all the struggles of human history we find struggles for the acquisition of land or commons, from the social domain. The privileged realized that, in order to link populations with chains, they had to make them materially dependent on them, and to do so they had to disregard as much as possible the resources, mainly the land, the source of all survival. In all civilizations we find a tendency to cut the means of subsistence. In Russia, Tsarra and the nobles saw in the 19th century the need to eliminate the servitude that came from the Middle Ages to avoid the discomfort that was circulating among the people, but … without ever giving land to the peasants so that they could not meet their needs. Because the only way to compel the baserritars to work on the big corporate farms was to do it without means of living.

We can all find it. That's why the popular classes were struggling to get land. Land and commons: to be able to take wood out of the forest, to be able to feed on land, to fish in rivers… Many Third World citizens are fighting the same fight to prevent multinationals from appropriating the forest, the women of the ethnic Shipyards in India, for example, in the defence of forests with sources of wealth around villages.

So there is something very important there. Because it is not only about what historians or anthropologists say, not: the popular classes did not seek to circumvent daily duties, in their struggles there was something truly important for the history of freedom, because the meaning they give to freedom was not to despise daily duties, but to assume them, they wanted to destroy relations of domination based on material dependence. And in them there is a very different meaning to freedom: to become enough car with autonomy, assuming the resources.

Today, even if it is in a more diffuse way, what is at stake among many people is the pretense of achieving greater material and energy autonomy rather than relying on multinationals to feed themselves as for energy…, that sense of freedom exists in the background, although those who are doing so are not always aware. People who practice autonomy are thus related to the traditional desires of the popular classes.

To give more details about this concept of autonomy… If we say that freedom is to guarantee one’s own survival, at least in part… this freedom cannot be guaranteed individually. This is a big difference with the other sense of freedom. Because it is impossible to guarantee for itself its survival. Survival is linked to relationships with the world, with nature, which implies the need for mutual help. Robinson Crusoe himself, symbol of the individualistic liberal desires of the beginnings of modernity, could not survive on an isolated island one day if Daniel Defoe had not thought well about the landing of Crusoe with boxes that brought several instruments. The large number of people who came with Crusoe to the island, all the technology of the craftsmen of the time, was not just in front of nature, but was the whole of society. The same if today we take the ‘Into the Wild’, the new version of the ‘robinsonkerías’, by Sean Penn, the hero who burns the ID and the bank card and launches into the jungle… it wouldn’t have lasted fifteen days if he didn’t have a rifle with him. Ensuring survival, even when you think you're alone, is always linked to social relationships.

The struggle for autonomy always requires criticism of technologies and liberation from our fascination with technology. Free from the myth of presumed technology neutrality

Autonomy is not material independence. No one on Earth is independent, we all depend on other human beings and other living beings. Autonomy is the construction of new connections, excluding asymmetric dependencies with the people and entities that subordinate us. These are the dependencies imposed on us by all the major industrial organizations in today's world. It's a lie that a farmer who works for a large agri-food industry, who gives him fertilizers like seeds, says he's in interdependence. Thanks to the asymmetry in relations, the large industry can cause this farmer to explode, which today is very clear, is unable to accept or reject the conditions imposed on him. The industry therefore obtains food produced by agriculture at a price lower than production costs.

The same is true of an indebted person and the bank, the indebted person is trapped in any asymmetric dependency. Therefore, autonomy is not independence, it is the struggle against asymmetric dependencies. This involves building interdependencies, and this is only possible in small groups of people who can speak, debate and negotiate endlessly on the small scale, in the village, in the community, in small groups of people. This autonomy is the reconstruction of personal and community interdependencies.

And this model must be new even to what ancient patriarchal societies had, where dominating roles were also played very hard, because, although the division of powers was not so asymmetrical, power prevailed over a person in the community. In the new definition of autonomy it is the ecofeminists who have gone further, trying to build conditions of survival overcoming interpersonal dependencies. I believe that this is what many people are trying to do in cooperative structures, by equitably distributing the obligations on the path of reorganising production, more in terms of the capacities and desires of people, for example, than of the sexes.

I’ve finished the book in a way… how to say… in a bit mysterious, I’ve put “Hunger, Hands and Earth” (“La faim, les mains et la terre”) to expand this idea of autonomy a little more. Trying to explain how this material autonomy is played, I have realized that it is played on three bases. “Hunger” expresses the needs, the needs we feel. The “hands” indicate the ability to do, including the technique. And “land” is a metonymy of resources. Autonomy operates on these three levels: needs, techniques or means and resources.

If we call autonomy to “ensure one’s own survival”, in everyday language we have three common formulas: “satisfy our needs”, “do it with our own means” and “live from our resources”. “Meeting our needs”, in short, is to meet the needs without having to go through the supermarket, without resorting to globalist capitalism that makes us absolutely dependent. It can be done in two ways: by self-production or by building networks of relationships other than those existing. Doing things yourself can also

be understood as “Do It Yourself”. But the more you try to live in autonomy, the more you realize that this individualistic view is an obstacle, each one in their corner producing their things… No, it is a relation of autonomy, collective. It is more important to build other exchange networks than your own production, otherwise it can lead to nonsense.

Political ecology and, more specifically, ecofeminists have joined the popular conception of freedom, in which freedom must have autonomy of its own.

I settled in the Tarn region, made my bread, we did it in a collective structure, we built the oven for that, we produced our vegetables, all that I loved. It is true that I have not made bread for a long time and I say to myself that every now and then “putain, you should do the bread again!” The problem is that that structure exploded, but in our environment new friends were established, among them the bakers who want to live from it, make large hornons of 80 or 100 kilos and sometimes have problems selling all these loaves. Therefore, from the point of view of collective autonomy, at a local level, I think that making my own bread, taking into account the energy costs involved in producing two or three kilograms of bread every week…, it makes much more sense to help these members to build their activity, so that they are not condemned in a few years to bow to the big bakeries and chains. It is more appropriate to organize other types of contacts and exchanges with them, or to collaborate or exchange occasionally in their work with goat cheeses in our case, because my girlfriend has goats. I don’t think we have to demonize the currency and pay the bread in money, we also have to do it well, because all of us alone will be practicing “Do It Yourself” in their house to continue to basically consolidate the industrial world. AMAP baskets or peasants, exchanges, nearby circuits… there are many efforts to live outside the globalized industrial supermarket.

On the other hand, “our needs” must be taken in the strongest sense, because we will never be able to meet more and more “our needs” if they are not our real needs, but those that the industrial system has suggested to us, internalized and imposed, which continually proposes new needs to continue accumulating capital. It is also necessary to consider the autonomy of the needs, which is also better done collectively than individually, to define what our real needs are, to analyze the needs to reduce them. With this desire for autonomy they have lived the popular classes all over the world for thousands of years, in France I would say that this is how the popular classes of the dwellings lived until the end of the 19th century, I would almost say that until the end of the Second World War, a large part of the population lived very autonomously. Not with all those needs that are imposed on us today.

Autonomy, “to do it by hand”. As we said, it's not DIY and do it with formulas like you, but more by collaborating in networks. To do this, it is necessary to rebuild the mutualism that has been at the center of the labor movement. This idea also raises the need to reflect on techniques, distinguishing those that serve us to alleviate our tiredness, legitimate techniques and technologies that seem to us to free us from all efforts, which make us dependent on the industries that produce these instruments, which force us to enter the labour market in search of money to achieve them. They are instruments that reinforce autonomy, as everyone knows, of easy production, easy maintenance and repair, of little complexity, of a human scale. The struggle for autonomy always requires criticism of technologies and liberation from our fascination with technology. Freeing yourself from the myth of presumed technology neutrality: “Technology is neutral, dependence on how you use it” is not true. It can be in the case of a knife, while a nuclear power plant, whether right or left, as a Soviet capitalist, can equally exploit and increase radioactivity.

When things have to be done by yourself, there is a certain limitation of needs. On the contrary, nobody and nothing satisfies those who do everything. The insane consumerism in which we are immersed is closely linked to this discontinuity between consumption and production.

In this field I will give publicity to the book Reencre la terre aux machines, which has just been published by a group called Atelier Paysan. Atelier Paysan is a cooperative dedicated to the production of work tools for the farmhouse, a group of engineers and peasants who find that throughout France there are very competent peasants in the crafts, capable of producing their own utensils or adapting those generated by the industry to their special circumstances, and who have been collecting the results of these ingenious peasants for years, preparing plans for these works and making them available to anyone on the Internet.

The third part, “living from our own resources”. That is, the resources we have close to us, those in our region. That is why autonomy can take very different forms depending on where we live, on the mountain or on the plains, in the city or in the forest... This requires that a population has at its disposal a wide range of resources. In the proposals to achieve this there is a version of autonomy that we could call “fascist bunker”: on one island or another or on an extensive land of 200 or 400 hectares in the difficult times that come to live with autonomy, an idea that extends among the elites.

On the contrary, the grass-roots classes have long been faced with another much more interesting solution: the attachment of an important part of the territory to common property, especially forests but also other lands, so that everyone can have that opportunity to supplement their resources to meet needs that can change with age, season, etc. Why in the Ariege region (in Occitania, the most important city is Foix) the peasants fought so hard in the ‘Guerre des Demoiselles’ against the ‘Code Forestier’ (new forest management law of the Parisian government)? Precisely because the law turned the forests into state property, prohibiting the local neighbors from pasting cattle in these mountains, bringing forest wood to fire, etc. In the jungle there are medicinal plants, for hunting, there are building materials, stone, etc. that a family doesn't have in their home.

Autonomy has, of course, a part of individual adaptation. For example, organizing a single garden for an entire people makes no sense, all the logic is to give each family its own land. But only such a people could function if that collective property was also present. The struggle for autonomy cannot therefore be developed unless it is accompanied by the demand for these commons.

What is the relationship between the socio-ecological situation and the modern conception of freedom? Why can the ecological crisis not be understood globally if it is not the social crisis, exploitation and domination of human beings?

In conclusion, they have built modernity, a modern idea of freedom, on the desire to be free from land and agricultural work. The leitmotiv of modernity is that the air of the city makes you free, manifested in various texts. But securing your life in the city is much more difficult, survival in the city is much more linked to technology and money than to the rural area. Today, however, we are becoming aware that the generalization of the urban life model carries the risk of the Earth becoming a desert. The last fans of the urban model have come to propose today the need to colonize Mars. Leaving aside if the air of the city can be free from the air of Mars… it is clear that if someone comes to live on Mars their dependence will be total, as in the technological, in everything else.

Only humans can breathe freely on Earth, we must not forget if we want to maintain the idea of freedom. Therefore, against those who propose an alien life, in this book we propose to recover another conception of freedom, compatible with our surface life, and that is autonomy.

“Earth and Freedom” is the immediate reference to the Spanish war, probably by Ken Loach’s film Land and Freedom. “Land and Freedom” is not only the Mexican revolution of the time of Emiliano Zapata. No, this concept of “Earth and Astucia” can be found on all continents and at all times: to recover land as a condition to access freedom.

1970s: they are among the precursors of ecofeminism. Photo: Wikipedia.

Macron made his press conference on 12 June to read the elections to Parliament. Above all, it has had the time to repeat that the right end and the left end are both landers exactly the same. Although he has criticised one and the other, he has opened up ideas of charm of the... [+]

I will spare you too many explanations and details, the esteemed reader who looked at this text. The issue is very simple. I'll talk about you, about me, about all of us. I am going to refer to the amazing travellers of this boat that is still floating without direction and ever... [+]

The crisis on the left jumps to Latin America. Until recently, progressive governments could be found on almost the entire map of the region. But things are changing in recent months. The three presidential elections marked a turning point: Daniel Noboa won in Ecuador, Javier... [+]

“And what is the weather she perceives for Thursday?” I asked the feminist militant that she was organizing the A30 strike. “The truth is that lately I’ve had my head in a conflict at school,” he replied with a serious face.

The Vox Solidarity party union called for a... [+]

When analyzing the history of social movements and protest, the most abundant studies are those of the Contemporary Age. Sources are more abundant, conflicts are more abundant, and researchers also share the view of the world of research. That is, as we pass through the sieve of... [+]

French and Spanish leftist parties and movements have a different relationship with the concept of nation and with nationalism. This completely conditions the relationship with the Basque nationalists. But why? The key to the theme lies in the different processes of creation of... [+]

Euskal Herrian "paradigma iraultzaile berria" zabaldu eta garatu nahi duen Kimua ekimen herritarra zenbait herritan aurkezpen bira osatzen ari da. Hala Bedi irratian Kimuako kide batekin hitz egin dute proiektuaren inguruan gehiago jakiteko.

“A ghost travels through Europe: the ghost of communism.” This is how the Communist Manifesto that he wrote 174 years ago begins. Marx and Engels began exploring the path of scientific socialism. In March 1871, the revolt that he sowed with the first program of workers took... [+]