Fundamental rights of migrants are systematically violated

- It is a sunny Sunday in November and I have gone to Hernani’s Intercultural Feminist Square on the occasion of the organization of the Hariak Resistance Stories Festival. Among others, Sahrawi lawyer Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye, who has lived in the Canary Islands since he was a young woman. It reaches the area of the suitcase, lively and vigorous, accompanied by the festival organizers and other participants. They don't lack enthusiasm.

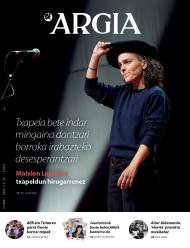

Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye Tindouf, Algeria, 1990

Lawyer and Saharawi activist, has been living in the Canary Islands for over 20 years. It operates on two lines. On the one hand, it acts on its own as a lawyer, especially with people in the process of regularisation and internationalisation. Meanwhile, in the activist part, he attends and denounces the migrants who arrive by sea in the Canary Islands.

First of all, I wanted to ask him to come forward. My name is Loueila, but people tell

me Lala. Recently, I've changed my surnames, migrants happen to us often. Before it was Loueila Mint El Mamy and now Loueila Sid Ahmed Ndiaye.

Why that change? For years I have had to fight against the Ministry of Justice to acquire Spanish nationality, because it did not seem to them that I was integrated into Spanish society, although I work as a lawyer in the country and have been living in

the Canary Islands for my whole life.

Of natural origin, it is Saharawi. Yes. I am Saharawi, a lawyer, and I work with people who come by sea to

the Canary Islands, and with people who are in a situation similar to the one I was once in: regularisation, nationality, with this kind of formalities. There I see the difficulties and obstacles encountered by the people I relate to, and that helps me to denounce their situation, to develop the activist facet of my work.

How did you choose to study law? Perhaps because I grew up in a refugee camp, or because of the influence that it has

had on me to make popular movements. Since I was very young I have fought for the Saharawi people, and this has linked me to the struggle of other peoples and other movements: feminists, pensioners, ecologists… It is essential that each of us assume its privileges to transform society. And I'm sure for all of that, since I was a kid, I was clear that I wanted to dedicate myself to the world of justice.

In fact, I wanted to be

a judge. Yes, I wanted to prepare oppositions for that, but in the end, precisely because of institutional racism, I did not. However, I realised that my place is that from here I can report the situations, I can work and I do not have a head – the state itself could be my main – to tell me that I cannot do so.

Why didn't they allow him to run into oppositions? He did not have Spanish nationality. For five years, the Ministry of Justice frustrated my life. The administration often acts in an absolutely passive and bureaucratic way – not only in terms of regularisation and nationality, but also in other areas – it is a

disaster that causes migrants to live permanently in a legal and legal limbo, truly exhausting both physically and emotionally.

In her case, she conducted her studies within the Spanish system and, however, hinders. I ended up with my colleagues studying the law, the master's degree we did the same year, I finished, I passed the examination of access to the law that we did, as an opposition, that is organized by the Ministry of Justice, but since the Ministry of Justice itself did not resolve my nationality dossier, I could not college. I realized how different they're being treated as foreigners, even though we passed all the peers through the same system: my peers, the ones who called Maria and Ana, had no

problem, and I, as Loueila Mint El Mamy called it, were asking me if I wanted to homologate the title, as if I had studied abroad. I spent six months in that limbo.

"My colleagues, the ones called Mary and Ana, had no problem, and I, as Loueila Mint El Mamy called it, was asked if I wanted to type the title, as if I had studied abroad."

This attitude of the administration is frightening. Yes, I do not know if it is passivity or if they do so intentionally, but whatever it is, in short, the result is the same: people are paying thousands of euros

to carry out regularisation procedures, to meet the criteria that are required of them – it is not a little – and then the administration does not answer or loses the file… That leaves it affected, only the one who lives knows its effects.

What are the concrete consequences of being in this limbo? For example, you cannot vote. It is true that I do not believe in the electoral system, but if I had ever wanted to vote for

a party I could not do so, even if I had paid taxes in the country and lived there. Then I could not travel, and that was important to me to see the relatives living in the camps, and then something else, which I think is more important, that the resources available to other citizens living in a state cannot be accessed.

.jpg)

In short, when we talk about institutional racism, we are talking about a person not having access by name, colour or nationality or being unable to access things in the same way as other citizens. I fought for three years with the Justice Administration, and I speak Spanish, I'm a lawyer, I have tools -- look at the situation of people who don't have those conditions.

You work with migrants arriving by sea in

the Canary Islands. What cases do they collect? There are a lot of serious cases. Today what I am seeing most in the Canary Islands is that they do not allow me to reach migrants as lawyers and activists, that is, the fundamental right of the person to choose his lawyer is limited, directly and intentionally, because they do not want migrants to have good lawyers, because this would stop the returns. This is what is happening right now in Gran Canaria: the Aliens and Borders Brigade and the head of the National Police of the Canary Islands have designed the way in which migrants do not have the possibility of obtaining a lawyer as anyone else would, whether it be a crime or not.

I go to jail many times for work and I see how different it is to play with a national person who has committed a crime and who has only made a migration. The fundamental rights of migrants are systematically violated, not only the right to a lawyer, but also the right to dignity and health care, among others. It seems that, as migrants, everything is worth it. That's where you realize things are really bad.

You have come to Hernani to present the documentary Here we are [We are] by Javier Ríos. What do they count there? We count on what happened after the Covid-19 crisis, which marked a milestone. Previously, the Aliens Act established that if they tried to enter the Canary Islands in an irregular way, a procedure was to

be initiated for their return to their country. I was in detention for 72 hours and you were admitted to a closed center for foreigners CIE.

And what about the pandemic? A lot more

people arrived. In 2020 20,000 people arrived and in 2019, about 6,000. They weren't willing to receive that many people, there were no resources, and there were a lot of people who had to stay temporarily in the port. Prior to the pandemic, what had been marked by Foreign Affairs was complied with, although people’s fundamental rights with the ICN were violated, etc., but that was the law. This changed after lockdown.

"I fought three years with the Justice Administration, and I speak Spanish, I'm a lawyer, I have instruments... Look at the situation of people who don't have those conditions."

Concrete measures were established in the Canary Islands. Yes. In the film we explain what happened between

December 2020 and summer 2021. The Ministry of the Interior issued an order, which we never saw on paper, we could not analyse, and it is clear that it was an illegality imposed directly on the Canary Islands. This order indicated that migrants arriving in the Canary Islands could not leave. So we lived in a Lesbos, a Lampedusa: people detained and locked up on the islands, couldn't leave. The Canary Islands are not the destination of migrants, but a stop. Most want to get there and then run away, but during the pandemic the islands closed.

How long did the situation last? Six months. This caused great frustration and great fatigue, which even left mental health ruined, that many migrants did not understand how, after paying for the trip, for example, if they wanted to go to France, they were suddenly trapped… That is seen in many refugee camps, and it is clear that the policy of the rulers is to tire people to give in and return to their country. In this case, this plan was designed as if the Canary Islands were not part of the Spanish state, and as if it were a limit: that people would be trapped. What

are they suffering? It doesn't matter, if you stay there and don't enter the peninsula...

And now how is the issue? Fortunately, things have improved in terms of inputs and outputs. People can leave with their own resources. Family support, passport etc. the one who

has can leave and those who are in the NGO infrastructure also manage to go wherever they want, even if the procedure is a little longer. It has nothing to do with the situation of these six months. On the other hand, in my view, other aspects have also improved in the Canary Islands. People are not in ports or ships, they are now in other spaces, in CATE. They may

be better, but at least there are no rats or beetles, there are showers, beds and the person has their intimacy. And to me that seems fundamental.

I would not like to end the interview without talking about the situation in the Sahara. In March, the Spanish President, Pedro Sánchez, stated that he would position himself in favour of Morocco in the case of the Sahara. I expect nothing from the rulers. Today Sánchez, tomorrow

Feijoo, past the other -- I hope nothing. The struggle of the Saharawi people is not transformed despite Sanchez’s attitude. The masks have fallen, yeah. Spain already had trade relations with Morocco, violated international law, violated European Court of Justice decisions by which Morocco cannot exploit the resources of Western Sahara. Spain already protected this illegal occupation by selling arms and economic agreements with Morocco. That activity has now only been called upon. Partly I think it is good, because the game has become apparent.

.jpg)

Do you have hope in the struggle of your people? If I have faith in the people. I have faith in humanity, although the work I do in my day to day produces enormous wear and tear. I think people are transformed, they're generous, they're trying to help them and they're going to get up when necessary. On the other hand, I have seen the position of many people in the Spanish State on the question of the Saharawi people, and that gives hope. It shows us that our struggle is fair. I think it's just resistance, and we've been for over 45 years. In any case, I believe that the two sides of the conflict are not the same and that a

contract has been signed with a stalker.

"The plan was prepared to get

people stuck in the Canary Islands. What are they suffering? It doesn't matter, if they stay there and don't enter the peninsula..."

I always compare it to bullying. Suppose a child has been bullied in school: the teacher can't cut the tortilla in half and put both sides around the table, distribute it. Here there is a victim and an aggressor, and the aggressor will also have to be answered, he will have to learn, but first we will go to the victim, you have to fix the pain he has done, ask for forgiveness, and then you will see what to do with the aggressor. It is the same in many other areas, such as male violence or illegal occupation.

In fact, in the case of Morocco and the Saharawi people it is not a conflict between equals. They have taken away

our land, they have torn us off, they have exploited their natural resources, they have killed the citizens… We cannot negotiate with the colonizers or the military occupants who, by the way, use the weapons sold by Spain. Let's start at the beginning. What are the consequences of this situation for the victim? He lives under occupation, violating rights, lives in refugee camps, dependent on humanitarian aid. Firstly, we are going to settle this issue. There can be no negotiation between the aggressor and the victim, there can be no mediation process when one party attacks the other.

Aljeriatik datoz Mohamed eta Said [izenak asmatuak dira], herri beretik. “Txiki-txikitatik ezagutzen dugu elkar, eskolatik”. Ibilbide ezberdinak egin arren, egun, elkarrekin bizi dira Donostian, kale egoeran. Manteoko etxoletan bizi ziren, joan den astean Poliziak... [+]

Kritika artean abiatu dira Gasteizko Arana klinika zena Nazioarteko Babes Harrera Zentro bilakatzeko obrak. Ez auzokideak, ez errefuxiatuekin lan egiten duten gobernuz kanpoko erakundeak, ez PSEz bestelako alderdi politikoak ez daude ados proiektuarekin: makrozentroen ordez,... [+]

Europako Batzordeak lege-proiektu berri bat aurkeztu du asteartean. Dokumenturik gabeko pertsonak jatorrizko herrialdeetara edo igarotze-herrialdeetara deportatzeko prozesua areagotzea eta azkartzea helburua du.

Harrera-herri euskaldun nola izan gaitezkeen galdetu zion Leire Amenabarrek bere buruari eta parean zituenei iaz, Gasteizen, harrera-hizkuntzari buruzko jardunaldietan, eta galdera horrexetan sakontzeko elkartu gara berarekin hilabete batzuk geroago. Amenabarrek argi du... [+]

“Bi pertsona mota daude munduan: euskaldunak, batetik, eta euskaldunak izan nahiko luketenak, bestetik”. Gaztea zela, Mary Kim Laragan-Urangak maiz entzuten omen zuen horrelako zerbait, Idahon (AEBak), hain zuzen. Ameriketan jaio, hazi, hezi eta bizi izandakoak 70... [+]

Aurrekoan, ustezko ezkertiar bati entzun nion esaten Euskal Herrian dagoeneko populazioaren %20 atzerritarra zela. Eta horrek euskal nortasuna, hizkuntza eta kultura arriskuan jartzen zituela. Azpimarratzen zuen migrazio masifikatua zela arazoa, masifikazioak zailtzen baitu... [+]

Hamasei migrante atxilotu zituzten otsailaren 6an Baionan, etorkinen eskubideen aldeko elkarteek salatu dutenez. Dirudienez, Baionako prokuradoreak eman zuen agindua. Operazioa autobus geltokiaren eta Pausa harrera zentroaren artean gauzatu zuen poliziak, tartean, adingabekoak... [+]