"My attitude to speak of Galician was only strengthened when I went to Brussels"

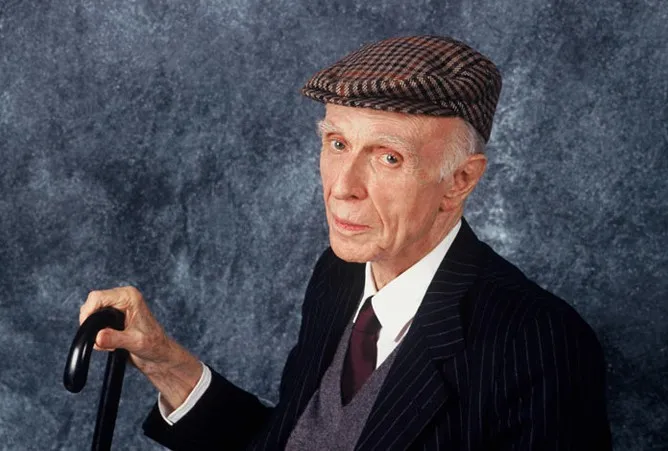

- Born in Galicia, he has worked almost all his time in Brussels. Despite his studies in Biology and Medicine, his similar work did not take place in the country and was once embarked on a fishing boat as a biologist. I was soon working on the European fisheries inspectorate. A highly prestigious writer, who has recently visited Euskal Herria through the Association of Basque Writers, and who inevitably has begun to speak of emigration.

Francisco Xavier Vázquez Alvárez. Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, 1957

His name is Xavier Queipo. Literature has all cultivated genera and several awards. The Galician author was one of the most prestigious, if he had not made life far from the country, in Brussels. We've recently been to Pasai Donibane, at the Hugoenea writers' house. It has dialogue on language, politics and life in general.

Together with his working day, he lived in Brussels. To say ‘Galego’ is to say ‘migrant’. But my thing was gold emigration. I mean, when I left Galicia, I had work in exile. I refer to 1989. That is why I wrote that essay, (H)emigration, (H)emigration, because “hemi” means that, half, saying that although what touched me

was emigration, it was nothing but a half, because I was in contact with those at home, even if it was by telephone. It is true that at that time there was no current technology, no application, but there was distancing, so I (h) emigrated. Of course, since then the communication paradigm has changed dramatically. Today, even if you are in the world at a distance, you cannot read the newspapers of your people, you can speak directly with your love hundreds of kilometers from your place through Skype, participate in debates and see live what is happening in the streets of Compostela, even if you are in the Hugoena of Pasai Donibane.

That is why he said “gold emigration”. Yes, then! What I had experienced had nothing to do with that overseas emigration. There was a time when the migrant would return or not return, not known. The relationship between those who were and those who were born in the place was postal, at best, and the letters of both arrived with difficulty. At best, migrants would return once to the village, visiting, and they would show that they had money, or walked through the thin streets of the village by car, they showed that they lived perfectly in exile, proud…

The emigration of then and now… The discourse on emigration of yesteryear serves no purpose today, although today nobody leaves the country enthusiastically. There is always a need, economic or social. However, the suffering, remoteness and semi-slavery of the current migrant

are not then. This massive emigration was due to poor management of the resources of the ruling classes, hunger and lack of work, the two sides of the operating currency. If Inditex wanted it, no one should emigrate, for example.

He emigrated when he owned two degrees: biology on

the one hand and medicine and surgery on the other. I was always a very honored, well-raised and educated child. Ha, ha... my father wanted me to study medicine. I wanted to study biology. And my father said, "I'm going to pay you for medical school." And I said, "OK. Pay for Biology.” And so we did. I did both. I liked medicine, but not when it comes to patient care, but when it comes to body disorders. I liked medicine and I was happy, and my father was also happy, because he overcame all the issues. Just like biology.

.jpg)

"They took me and sent me to Newfoundland. It was 1984. We were paid 300,000 pesetas a month [1,830 euros], a lot of money! He earned more than a doctor."

And he started working as a doctor. I also did two jobs, one paid and one volunteer. In 1984, there were many doctors in the field. One week we worked in one place, and two days later, covering a shift. It was a very unpleasant thing, always from one side to the other, without a doctor's seat. In that, one time, a friend said to me, “What are

you walking there! You are also a biologist and on board the boats you already have enough work. Scientific observer, you!” That friend made my way to that work. The director of the department was a billiard, but of night worship, despite everything, of Opus Dei! At that time, the most important governor, the favorite, was Pinochet. That's where he gets the bills!

Still, he got the job. Yes, I had the religious apathy that I wanted, that of home, and I easily separated that bilbaíno. They took me

and sent me to Newfoundland. It was 1984. We were paid 300,000 pesetas a month [1,830 euros], a lot of money! He earned much more than a doctor, but the work was heavy: he had to spend between four and six months at sea, and the sailors of the boat were living. And I started going to Newfoundland and Norway on those ships.

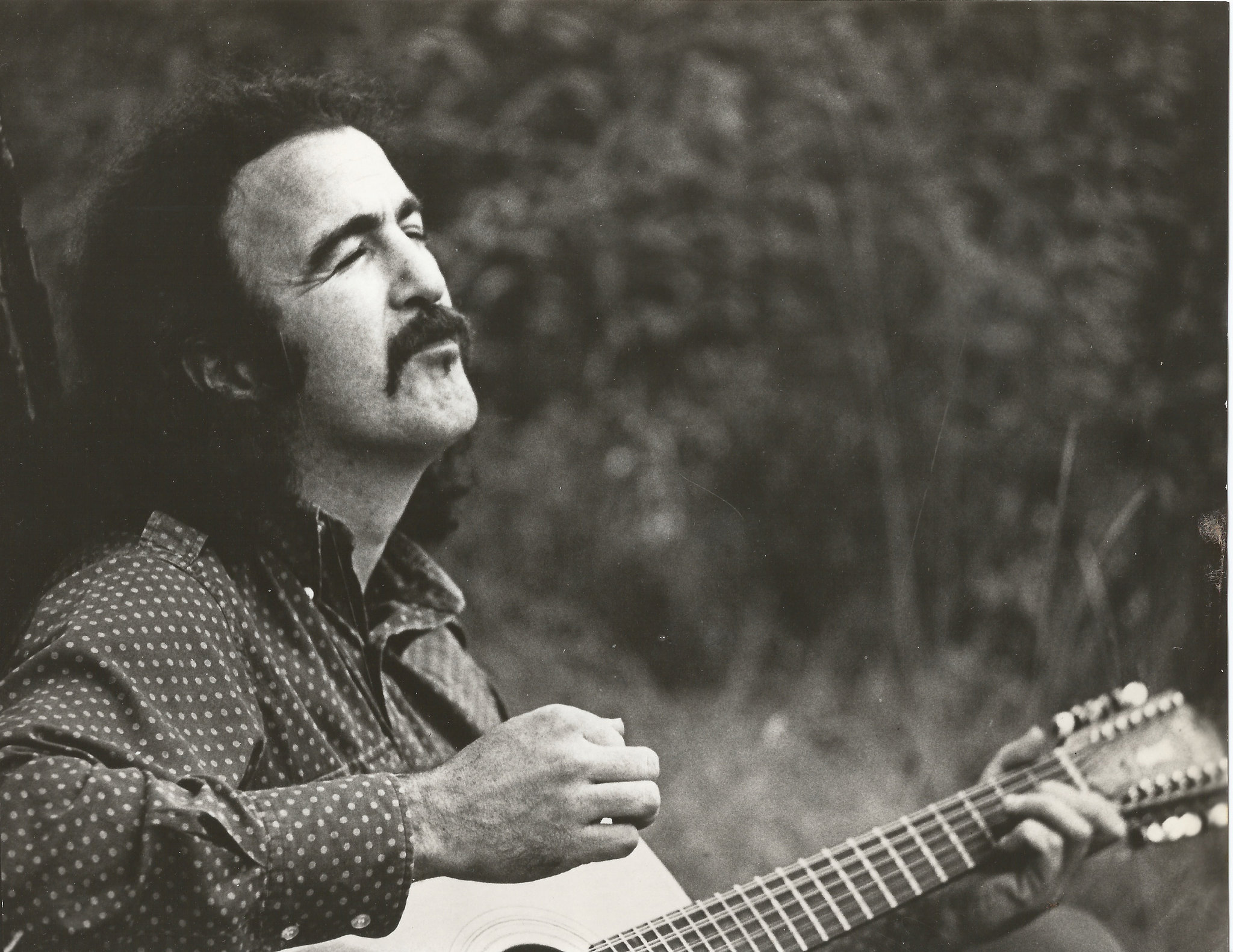

What work did you do at the pottery? Every time the fish came to the ship I had to measure it, weigh it, sexit, which species we collected… It was hard work and I was a street child! We spent about three

months without touching any port. So what did I do? I took a bunch of books, and the cassettes of yesteryear, and I learned a lot. And on the other hand, I also got a doctor, and once, speaking, I told the captain, he was a doctor. “Great!” he told himself, because at that time, on the ships, when someone got sick or injured, they used the sea radios to consult the doctor on call and at least complete the mildest diseases. However, since I said I was a doctor, I began to care for the sick, our boats and the rest, until one day I diagnosed peritonitis by radio. So the accounts!

Did you diagnose peritonitis by radio? Yes. The captains of the boats had a sort of handbook full of body images. These images were divided into squares, and the captain of a boat said a page, talked about a picture of a square, and the on-call doctor, from another boat, would give him some guidance, always by radio! In that case, by radio, I told the captain of the boat that it was mandatory

to evacuate that fisherman.

From the boat to the boat, the captain of one, he, and the doctor of another, you… So! I gave him guidance to take care of that fisherman, the captain complied with what I was saying, and in the end I told him that it was peritonitis and that the patient had to be evacuated. Then the captain of his boat, “But we cannot go to the port, we would lose four days.” And I said to him, “You have to decide that, you are the captain, but if you do not bring the sick person to the port I will have to file a

complaint against you.” This captain and our boats talked and managed to somehow reach a helicopter. Canadian. So that fisherman was released. And then again the accounts!

“Again?” Did he do what he had to do? Yes, but the sound spread, and since then I started opening the consultation every day, on the same boat, at eight in the morning. “Here from the Virgen

de la Barca… Here from Menxueiro…”, they started calling me from ships of each other, and at the end of the campaign I received several telegrams from shipping companies asking the National Institute of the State Sea to recognize me as a doctor. He had medical leave, but at that time many names were still made with his fingers and another was called. And there's already my work in the baccalaureates. At least I kept telegrams. They made me a lot of joy: 27 letters, 27 of them looked like gifts to me. Some also sent me a cash check. That ship was prevented from traveling to the port, a three- or four-day trip, and I knew that my money check was small or big, that it wasn't too much for them, that they would lose much more when they were those days without fish.

.jpg)

"Since I said I was a doctor, I began to care for the sick, our boats and the rest, until one day I diagnosed peritonitis by radio. So the accounts!"

They did not receive him as a doctor and, as we know, he has worked his time in Brussels, in the European Fisheries Directorate-General, in the inspection. How did he get to that job? Between

1986 and 1989 [Vigo, Galicia] I worked at the Mariñas Research Institute: I represented the Spanish State in the Arctic fishing paper. Since these were specific places, there was no open competition, a certain knowledge had to be demonstrated, without more. Once, on the boat from Vigo to Copenhagen, I saw an announcement in the newspaper El País to occupy two inspection posts in Brussels and presented myself.

And so came the work of Brussels… But not instantly, because we were at sea, on the way to Copenhagen, there we had to go the port. So far I couldn't do a job interview. Up to five interviews! One in English, one in Portuguese, one in Spanish… I had to walk the languages I spoke at the time, and then I have also learned other languages. This happened at the end of September 1988, at the beginning of October. At Christmas I got a telegram asking if in January I could start working. “Rooting, I have something to fix before! I will start in February,” I replied sprayed. They did, and so I started, in Brussels, but always working. One in Turkey, another in Georgia, or in Romania, or in Bulgaria -- everywhere. My work, my office, has been itinerant, real and eye-catching. Bizpalau in one place and air to another! And I've done

it here and there. To say, I've written more in airplanes and hotels than in my house.

You write in Galician, you have all the cultivated literary genres. However, he

did his studies in Spanish, necessarily at that time, the Galician had to work differently… To work, and to study it, I would say. I've made three linguistic dives in my life. On the one hand, as a child, every year, I made a quarter of the Galician communication. Our parents lived in the countryside. They weren't farmers, but they had finca and land. They had landlords and they didn't touch the shock debt. As a child, our family went there to spend the summer. The course ended in mid-June and began for the first time at October parties. We had a three-month vacation in the country and in those three months we were field kids. The parents tried to speak in Spanish, but they hardly managed to. We lived in Galician, unlike the city.

Three dives, he said. Before the second dive, a rocket that gave

me a bad look at the Galician. In summer we immersed ourselves in the Galician, but the other nine months lived in Santiago de Compostela with a very pure Spanish model. At UBI we had a literature teacher who taught us Galician classes. But that teacher was a mess, he was very authoritarian, he's a galegist, but a simple canyon: the students had a bad laugh to humiliate, he was a very violent, and so I didn't give a good trace to our language. The Galician, the language, if I accompanied that professor, didn't want Galician. Then, when I worked in the potters and freezers, when all the shellfish were Galician speakers, I made my second linguistic dive.

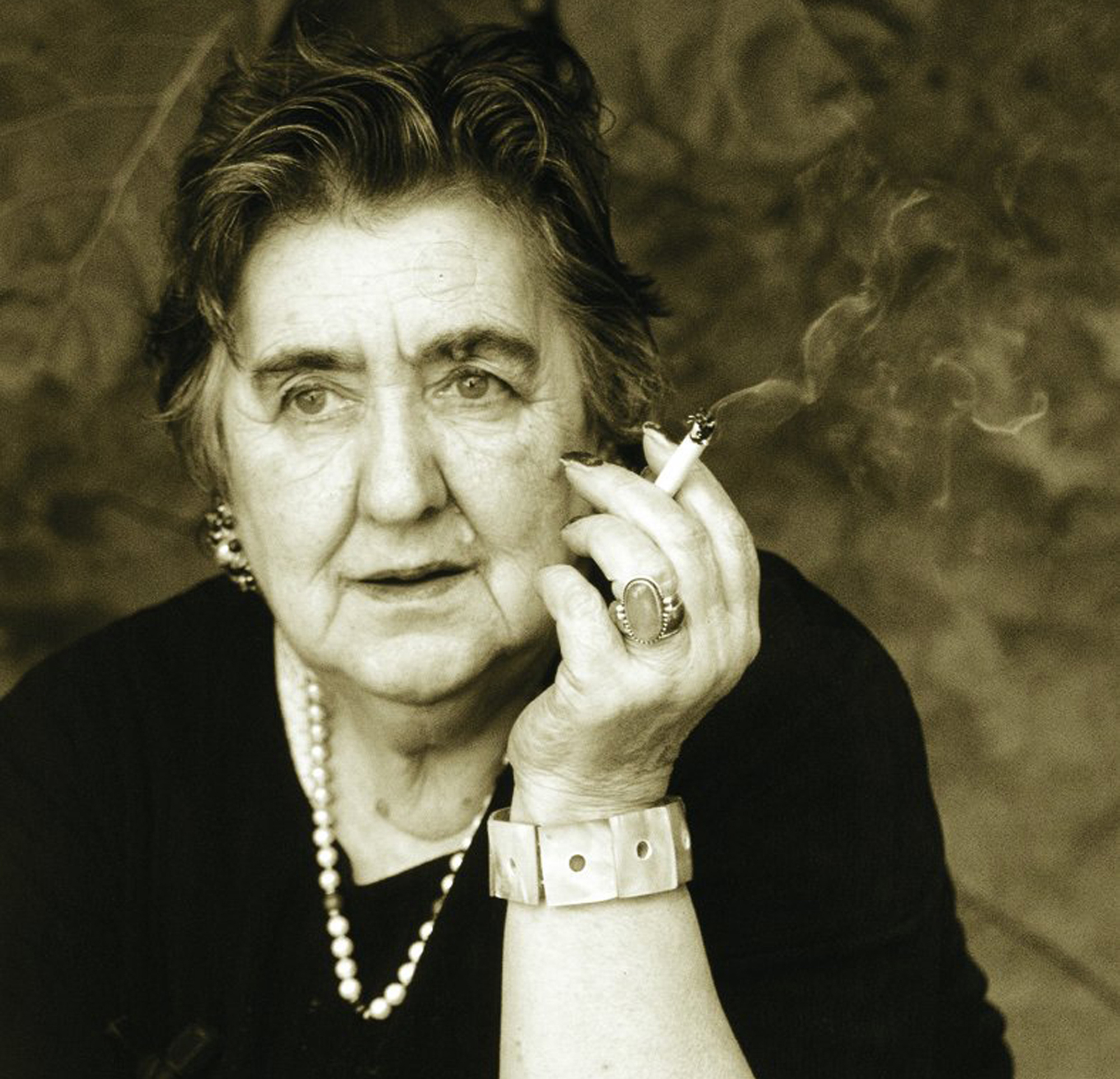

We have the third -- the university, where I started speaking in Galician. First, the Lost Letters Day. Then, when between friends and friends we started going to the campsite and to militate around the political parties. At that time, the parties of the extreme left, who expelled gays from the party, also referred to Spanish. In 1986, I started interacting with my husband and he made a

language change in me. Her husband belongs to a neighborhood in Vigo, surrounded by Grapa. Total, one day he said to me, “I speak at home as a Galician, and also among friends. If you believe it, we also do it in Galician.” And so on. And this attitude was only reinforced when I went to work in Brussels in 1989, because that's when I started writing and Galician.

He mentioned Grapo, which leads to the then armed struggle. They were shot from Vigo in 1975, Xose Luis Sánchez Bravo and Xose Humberto Baena from FRAP... A

year earlier, in 1974, when high school ended, [Salvador] Puig Antich was killed in the garrote. That course a professor founded the journalism club. That professor was not from the left, it was not a Mendez Ferrin of the institute of Vigo, for example. Ramon Valle Inclán began to explain Carlist wars, this and that, and I began to understand the issue of the sides, the liberals on the one hand, the conservatives on the other. We once talked about civil war, but without indoctrination, somehow from the equation. In that, when he told us about garrote, when I heard it, I found it a crime of humanities to kill someone with garrote. Awesome.

He became aware. By sewing the ears in one and the other, I realized that the Franco regime was not only benign, but violent, and bloody. On

the other hand, there were friends who were against the regime. I had friends. And they also said: issues of war, concentration camps… Our mother also said so, but since it could not be otherwise: “Yes, right here, along with Padron, there was a prison camp. I was in an old sugar factory. So many years were the prisoners!” And we knew that the professor of geometry, for example, was lieutenant in that small concentration camp. Or what my father said to us at another time: "So they gave him the title because he was a Phalangist." And I started tying the strings. Professor of Pharmacology, let's say, because he was a professor, uprising, not a "national", a priest or captain of the war for crimes. And so are our accounts ...

"So my husband said to me, 'I speak at home about Galician, and also among friends. If you believe it, we also do it in Galician."

.jpg)

* * * * * * *

List of tasks

“I studied two degrees at the same time. And then I would go out with my friends, I was a gautxoria. And he also had sporadic relationships, not always, but we had to be careful. And he was also anti-Francoist, and we were doing our lantxos. The only way to do all of this is to take advantage of time. Task list, ‘task list’, began to say about twenty years ago… I’ve done it since I was young! Make the list, fulfill your task and delete!”

Sexual diversity

“It was another time, sexual diversity was not fashionable, not far away. All my friends were in a left-wing environment, and I also entered there, with friendship and sympathy. Once, on one side of the left, a militant was expelled from the party for being gay. Being gay was apparently a bourgeois degeneration. Communist Movement, ORT [Revolutionary Workers Organization]... were Maoists, but as closed as those on the right in terms of sexual diversity.”

From black to green

“This year Professor Carlos Callón published O libro negro da lingua galega. This book is very important and I said to Callon, ‘Excellent work. In all aspects they gave us the wood and it has collected the testimonies. Now we have to write a green paper of hope.’ It is time to move forward, we have to act as before, seeing that young people do not speak Galician, even though many of these young people are schooled for the first time in history. We need a green paper to spark debate and then write the white paper to change the political paradigm.”

LAST WORD

An enriching catastrophe

“I started to form the dictionary on my parents’ hacienda, the name of a bird like this, of a tree, of a plant… “Let’s go to nests!”, and the usual thing: take eggs, waste the nest… From the ecological point of view, a disaster. As for life, everything is enriching”

Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914-1999) idazle argentinarrak 1940an idatzitako La invención de Morel (Morelen asmakizuna) eleberria mugarritzat jotzen da gaztelaniaz idatzitako literatura fantastikoaren esparruan. Nobela motza bezain sakona da, aparta bere bakantasunean, batez... [+]

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

Aste honetan aurkeztu da Joseph Brodskyk idatzitako Ur marka. Veneziari buruzko saiakera. Rikardo Arregi Diaz de Herediak itzuli eta Katakrak argitaletxeak publikatu du poeta errusiar atzerriratuari euskarara itzuli zaion lehen liburua.

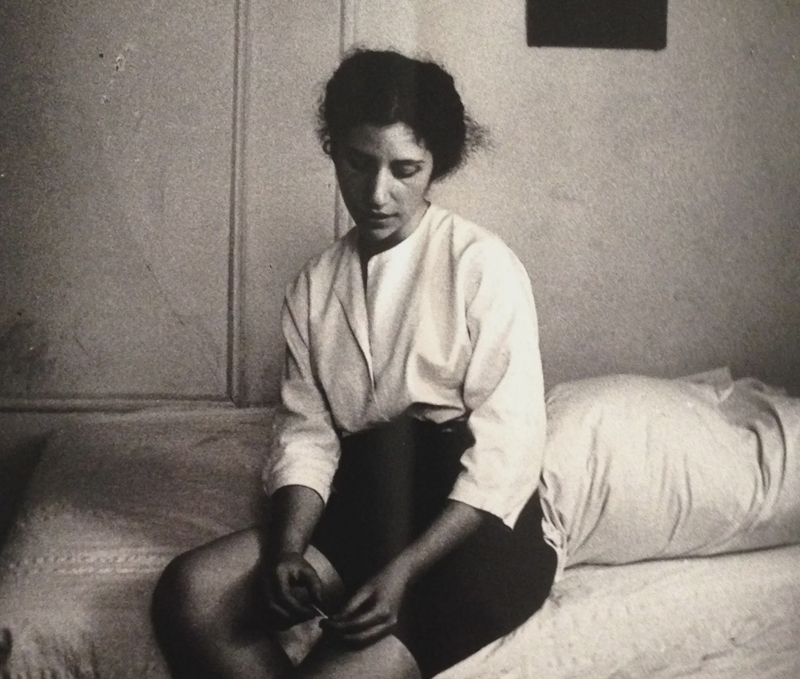

"There were women, there they were, I met them, but their families locked them in the mental hospital, put them in electroshock. In the 1950s, if you were a man, you could be a rebel, but if you were a woman, your family would lock you in. There were some cases, and I met them... [+]

Gauza garrantzitsua gertatu da astelehen honetan literatura euskaraz irakurtzea atsegin dutenentzat: W. G. Sebalden Austerlitz argitaratu du Igela argitaletxeak. Idoia Santamariak egindako itzulpenari esker, idazle alemaniarraren obrarik ezagunena nobedadeen artean aurkituko du... [+]

Asteazken honetan aurkeztuko dituzte Erein eta Igela argitaletxeek Literatura Unibertsala bildumako hiru lan berriak, tartean Maryse Condéren Bihotza negar eta irri (ene haurtzaroko istorio egiazkoak). Joxe Mari Berasategik euskaratua, idazle guadalupearraren obra... [+]

Wu Ming literatur kolektiboaren Proletkult (2018) “objektu narratibo” berriak sozialismoa eta zientzia fikzioa lotzen ditu, Sobiet Batasuneko zientzia fikzio klasikoaren aitzindari izan zen Izar gorria (1908) nobela eta haren egile Aleksandr Bogdanov boltxebikearen... [+]