Do those who feed us win with dignity?

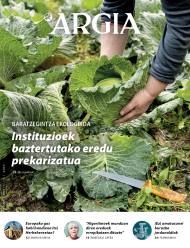

- On Saturday for one morning you went to the local market with the fabric bag and bought it directly from the gardener, “face” with respect to the super. You have returned home proud of your small act for the environment and food sovereignty of Euskal Herria. You have discussed with your colleagues that you are preparing food, if it is not inaccessible to the precarious population to eat vegetables grown locally, contemporaneously and healthily. When you take the leftovers of vegetables you just steal to the compost, the shells, the nuggets and the edges of the vegetables have returned the question: what do you know about the precariousness of the gardener who has sold you “face” in the market? Do you have a better ally than that horticulturist to guarantee daily feeding in the face of speculation and world wars?

The Biolur Association and the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) have carried out the "Duina" study (here the presentation chronicle) to, among other things, accurately quantify working hours in organic horticulture and calculate the cost prices of vegetables. To this end, 11 ecological horticulture projects have recorded the hours dedicated to each work during 2021: this has measured the hours dedicated by each horticulturist to work in the garden, for sale, management, collectivization of the project (e.g. reception of visits and explanation of experience) and care work (training, evaluation of projects, etc. ). Revenue, expenditure, depreciation and loans for each project have also been analysed. Also the area occupied by each vegetable, the harvest received and the quantities sold. The collaboration and trust between the eleven projects that have participated in the research has been enormous, as they have shared with others all the economic data of their kitchen with total transparency. With the support and interpretation of the technicians of Biolur and the researchers of the UPV/EHU (Mirene Begiristain and Aintzira Oñederra), this collective study has led to the daily known reality of the experience of the years: the hours each dedicates to the project, the net margin they obtain annually, the work and benefits each marketing medium bears. Each project involved in the study has received a technical report at the end of the process to improve its viability. And with the data from all of them they have also developed a joint report of conclusions. The following is the panorama of ecological horticulture that the data of this study show:

Lots of hours of unpaid work

The first conclusion of the investigation is that the Agricultural Labour Unit (UTI), measured by the Basque Government in 1,800 hours a year, is very short of reality: on average, organic gardeners include 1,953 hours a year, that is, 10% more hours of work than those calculated by the government in the UN, among which there are 53% more projects.

If you take into account the calendar of 251 working days, i.e. weekends of leisure and holidays marked exclusively in red (no holiday), only in the orchard each horticulturist invests 7.24 hours on average a day, according to data from the "Duina" study. However, considering the other tasks to be offered to this project, the average of hours per day is 8.05 hours. The daily working hours are increased if an annual work schedule of 229 working days is foreseen, that is, weekends, holidays and 22 days of holidays in red, in which case in the vegetable garden of each working day each horticulturist would enter an average of 7.94 hours and each working day to perform all the work related to the project would be 8.91 hours. The study highlights that these hours of work are minimal, since very concrete works have been measured when carrying out the research, there have been no moments of rest and many other unforeseen works are extracted daily. It is therefore clear that organic gardeners have a great workload.

If all hours worked were paid, the annual economic result of these projects would be negative. If all these working hours were collected by horticulturists according to the salary that the Charter of Social Rights qualifies as dignified (16,800 euros per year), the projects would incur an average annual debt of -2,440.69 euros. If horticulturists were to charge all hours taking into account the Reference Income of the Ministry of Agriculture (EUR 30,662.23 per year), the projects would make an average annual hole of -EUR 13,943.06. It must also be borne in mind that in almost all the projects that have participated in the study, the owners are the gardeners. In view of its viability, land ownership is fundamental and yet projects are kept alive by a lot of unpaid work hours. In practice, the average annual wage for organic gardeners is EUR 14,990.

Research has revealed the constancy and linkage of gardeners with work: working hours in the garden cannot be done when "desired", times, time and hours of sunshine. To this must be added that the projects do not allow for the hiring of a substitute worker, so that horticulturists have great difficulty in enjoying holidays and rest days.

The Duina study has calculated in detail the cost prices of each vegetable. To this end, it has taken into account the working hours that have been devoted to each vegetable throughout the year (based on a salary worthy of the Social Charter) and the sales quantities of each vegetable. The result is serious: organic gardeners generally sell vegetables below the cost price, as can be seen in the table on page 27. To determine the prices that we find in any market, the study provides two references: one, the minimum and maximum prices used by the horticulturists participating in the study in the face-to-face selling. On the other hand, the Biolur association gave as a reference for the year 2021 prices, much taken into account by those who join the ecological horticulture when determining their prices.

Vegetables that are regularly paid are Italian pumpkin, lettuce and bell pepper, the production costs of which are close to the reference prices established by Biolur and the minimum and maximum prices used by horticulturists at fairs. In the case of pea and tomato, the cost price is between the minimum and maximum selling prices at fairs, but is higher than that proposed by Biolur. And in the case of carrots, broccoli, green beans, Gernika pepper, leek and onion, the cost prices are higher than those proposed by Biolur and those used by producers at trade fairs in general.

.jpg)

Multiple and short selling channels

The eleven projects that have participated in the research use short and multiple marketing channels to reach buyers. 40% of the projects have two marketing channels, 50% 3 marketing channels and 30% 4 channels. This, of course, frees them from dependence and allows them to negotiate prices.

Consumption groups or the sale of baskets are, on average, the most productive route for organic gardeners, who get half their sales on average. Next, small shops in the villages are the most significant routes: 80% of the projects sell them in small shops and get 22% of the sales. Half of the projects are sold at fairs and get 11% of sales.

Climate is a model that requires emergency, but forgotten by subsidies

The study highlights that ecological horticulture has very positive effects on society and on Earth, which are important for the current climate emergency: the use of local varieties, the use of natural treatments, landscape and soil preservation, waste reduction strategies per ecological fertiliser such as plastic, etc. To this must be added the benefits that the use of short marketing channels brings to society and Earth: reduction in transport, impact on the local economy... According to the "Digina" study, "these positive effects are not reflected in public aid received by the horticultural sector, in direct (subsidies) or indirect (e.g. by prioritizing direct marketing channels in public purchasing or taking into account healthy eating criteria). We do not mean that horticulture is a model dependent on subsidies, but the positive effects of ecological horticulture must be compensated, given the importance of the contribution and the difficulty in achieving a decent monthly wage". In fact, organic horticulture projects earn on average only 5.42% of their subsidy revenue.

Questions generated from data

How can ecological horticulture attract young people with an unpaid workload? How will the Basque authorities achieve the objectives of the quantity of organic crops set for 2030 if the level of precariousness of the sector is as follows? – hydroponic and production based on fossil and chemical fuels, so-called "green"? At a time when the rise in food prices has aggravated us, and in the face of food shortages, do we value so little that agricultural land becomes energy parks the ability to produce daily food as a people? If 90% of global deforestation is due to the food industry (two-thirds of which is due to the production of soy and palm oil), and 44% to 57% of greenhouse gases are caused by agro-industry, what is the same as local organic cultivation and promotion of short sales channels for climate emergency? Just as governments have paid directly a share of the price of gas oil purchased by citizens, can they not take similar measures to allow all citizens to buy indigenous organic food? How can we connect ecological farmers and citizens to reorganize our precarious lives driven by the capitalist system, so that healthy food is guaranteed for all, and produced in decent working conditions?

Do you want to defend organic gardeners? The agroecological movement of Euskal Herria and ARGIA have pulled the Lurra Herriari Deia t-shirt. Get it here.

Gaur abiatu da Bizi Baratzea Orrian kide egiteko kanpaina. Urtaro bakoitzean kaleratuko den aldizkari berezi honek Lurrari buruzko jakintza praktikoa eta gaurkotasuneko gaiak jorratuko ditu, formato oso berezian: poster handi bat izango du ardatz eta tolestu ahala beste... [+]

Iruñean bizi ziren Iñaki Zoko Lamarka eta Andoni Arizkuren Eseberri gazteak, baina familiaren herriarekin, Otsagabiarekin, lotura estua zuten biek betidanik. “Lehen, asteburuetan eta udan etortzen ginen eta duela urte batzuk bizitzera etorri ginen”, dio... [+]

Euskal Herri mailan txikitik handira agroekologia sustatzen duten zenbait elkarte eta kooperatiba ataka larrian daude, finantziazio iturriak bertan behera geratu ostean. Erakunde publikoetatik, berriz, elikadura negozio gisa ikusten duten proiektuen aldeko apustu irmoa nabari... [+]

Gipuzkoako hamaika txokotatik gerturatutako hamarka lagun elkartu ziren otsailaren 23an Amillubiko lehen auzo(p)lanera. Biolur elkarteak bultzatutako proiektu kolektiboa da Amillubi, agroekologian sakontzeko eta Gipuzkoako etorkizuneko elikadura erronkei heltzeko asmoz Zestoako... [+]

Emakume bakoitzaren errelatotik abiatuta, lurrari eta elikadurari buruzko jakituria kolektibizatu eta sukaldeko iruditegia irauli nahi ditu Ziminttere proiektuak, mahai baten bueltan, sukaldean bertan eta elikagaiak eskutan darabiltzaten bitartean.

Ibon galdezka etorri zait Bizibaratzea.eus webguneko kontsultategira. Uda aurre horretan artoa (Zea mays) eta baba gorria (Phaseolus vulgaris) erein nahi ditu. “Arto” hitza grekotik dator eta oinarrizko jakia esan nahi du, artoa = ogia; arto edo panizo edo mileka... [+]