"We didn't think they would take five people to the platoon firing."

- They were the last Franco rifles: Txiki, Otaegi, Sánchez Bravo, García Sanz and Humberto Baena. Among them was Pablo Mayoral, FRAP, the Revolutionary Anti-Fascist and Patriot Front. Major was sentenced to death, although he commuted to 30 years in prison. He has an intense memory of his fellow men shot forever.

Pablo Mayoral Rueda. Madrid, 1951

He was a member of the Communist Party of Spain (Marxist-Leninist) and the FRAP. He was arrested in July 1975 and prosecuted at the Francoist war councils. José Luis Sánchez Bravo, Ramón García Sanz and Xose Humberto Baena were sentenced to death in the same trial, although he later commuted the death penalty and gave 30 years in prison. Two and a half years' imprisonment and free from the 1977 amnesty law. In one way or another, he continues to militate. She currently works in the Commonwealth of Ex-Franco Prisoners and the State Coordinator of Support for Querella in Argentina, without despair.

What do you have on September 27?

The day my three party mates died. Two other members of the Basque Country were also killed that day. We were fighting against Franco, against dictatorship. September 27 is an unusual day, there is no good memory in me: we were arrested, we were kept isolated in the SMI [General Security Directorate, in Madrid], we have been there for twenty days in the lower camps, ten days later we were judged… Everything happened very quickly. We celebrated on 27 September in Madrid, as is celebrated elsewhere, we pay tribute to those who fought one way or another and to all those who were arrested, isolated, tortured, war council and shot in 20 days.

What was that dictatorship?Some say

that Franco's dictatorship was softer in the end, but it is just the opposite: in the end the dictatorship was harsh and cruel. Everyone, some say that the dictatorship beat the extreme left, but not sir!, the dictatorship beat everyone, impeded everything, manifested, gathered, expressed… It impeded everything, and impeded the whole society! And that ban was monitored by hundreds of civilian guards, hundreds of policemen and members of all kinds, serene and eleven chibates. These repressive forces fired at everything that was moving, not in the air, but to play, and especially against young people.

They were shooting to hit. But you faced. In the

black night of Franco you couldn't live, you had to do something. Our life was rebellious, there was no other. Or be at home closed and do nothing or fight the dictatorship. If I worked at university or workshop, the debate was unique: “Why don’t we have freedom? How to break the dictatorship?” It was therefore logical that he should militate there or here. It was a rebel. One example: The Beatles performed a performance in the bullring of Sales [Madrid, 1965] and the police threw people in their uniform, their pistol, their tassel. At that level we lived. The police mandate consisted of harshly suppressing people at hard cost, using weapons against those who rose up against the dictatorship.

At the age of 18-19 he began to militate in the PCE (Marxist-Leninist). Why opt for this?

The environment itself encouraged you. I did a year studying Technical Engineering in college and made friends of the PCE [Communist Party of Spain]. Then I had to leave the studies and start working there and here, and most of the time in the American multinational NCR. At that time I met people from OSOA and from PCE (m-l), then came the FRAP, and I chose like many other young people. There was a lot of militancy among friends, we would be between 20 and 30 militants, just like in the neighboring neighborhood, we were activists and agitators, we would distribute leaflets, paint or form a command to make a demonstration.

.jpg)

"We were fighting for life and, therefore, against dictatorship. The only way to stop our struggle was that harsh and harsh repression."

I thought few people chose.

No. I remember that we were forming the FRAP commissions, and that every day a group was formed in different neighborhoods. We were not a majority, of course, but a lot. On the other hand, there was no way to register militants, we were in great secrecy, and with it something else, repression, terrible: The police had no good offices until the militants were imprisoned, which necessarily led to the reversal of many newly initiated militants against Franco.

I had no measure of that repression until I have read it. In 1965 our militant, José Delgado

Acero, died in prison after 21 days in prison for torture. That same year, Ricardo Gualino was almost killed when he was issuing leaflets in Getafe; the bullet was shot by the police and entered the cheek. Enrique Ruano was killed in 1969. In 1972, Cipriano Martos was killed: He died in Reus after torture by civilian guards and was about to die in a small hospital for several days. In 1975, Carlos Urritz Geli and José Gómez César were wounded with bullet, one in Barcelona and the other in Madrid, when they worked as propaganda. Eduardo Serra Torrent died the same year from torture in Valencia and two years later Jaime Pazos Recaman in Barcelona; in both cases they were captured in a large raid against the militants of our party. I said, repression was savage. At that time, Spanish prisons were full of PCE militants (m-l). We were fierce wrestlers and we had people in each other.

What were the objectives of the struggle?

Our party and FRAP had great statements: we opted for the federal republic, against US imperialism, for democracy and freedoms, we defended self-determination, the free university… but, along with them, we also had other struggles: once we opposed the increase in bus prices. We called a bus boycott, and I remember that day we didn't get into the bus, we walked up to the bus and inside the civilian guards with a rifle! We were also fighting for a traffic light, because neighborhoods grew, but in an absolutely chaotic way, and they didn't put traffic lights if you didn't do power and war. Once again, our militants burned an orange store to demand proper salaries for the collectors: we fought for everything and everything. However, most of us would say that we were trying to fight him.

Drowning?

Against that black night. Everything was forbidden, there was no way to breathe, we lived about to explode. We were big families in every house, four to five children everywhere, we had to leave the house very young looking for bread, there was no family support, because the family itself had a lot of work to keep. We were fighting for life and, therefore, against dictatorship. The only way to stop our struggle was that harsh and harsh repression. There is no more to see those great mobilizers of the time after Franco's death, when it was not yet clear that the police would not shoot you. And that's what happened ...

In the years

following Franco's death, between 1975 and 1981, the police and civilian guards killed 134 people, and fascist gangs the same. That is, some 300 people died fighting for democratic rights!

A police officer died at the demonstration on 1 May 1973. Increased repression. Two years later, a FRAP command killed police officer Lucio Rodríguez. Then the great raid and hundreds of detainees. Among them, you. Days later, FRAP also killed a civilian guard.

Yes… We were a lot of people fighting and we took the regime very well. And so, in Madrid, in Barcelona, in Seville, in Valencia…, after several actions, the regime – not the police, not the Civil Guard, but the regime itself – launched this manoeuvre, which eventually led to the shooting of 27 September. The actions of ETA, and those of others, joined those of us, and the regime decided to give an exemplary punishment. Hence, they “come with delayed hunger” from Al alba (at dawn), from Luis Eduardo Aute. The conclusion, four war councils, which were made barely, running a month and in haste, with no more or no detail: thirteen death sentences were killed first, eleven after, five activists were finally shot…

.jpg)

"Leaving the police station gave me a lot of joy, so much so that the lawyers asked me for the death penalty for telling me, because it didn't alter me."

What memories do you have of SMI?

It was the entrance to the castle of terror. The security measures and the police themselves told you that you would see red and two. And we saw the reds and the blacks, yeah, for nine days. Social [police] didn't go out, surrounded us, glued us constantly. It was very hard. Going into jail was resting. All of this happened in the SMI, but you don't want to remember it. I often go ahead of what was the DGS [Portal del Sol, Madrid], I see the verges of the cells and my hair is still clear. For many years there were negative ones, but there is no memory: In 1808, we recall those who fought against the French, those killed by COVID-19, the attacks of 11 March, and on the contrary, for many years there is nothing to remember what that unfortunate building was, who was there and what misunderstandings they did.

It talks about memory.

Historical memory, they say. Many Madrid and state fighters against Franco went through the DGS. It should be a museum against dictatorship and torture, a place to pay tribute to the fighters who saw the Reds – some died there, as the Basques know. The public health issue should be the transformation of DGS into a museum of this type, fundamental. Unfortunately, some try to conceal these facts in order to deform history, to deform that barbarism.

Arrest, isolation, torture, war advice… When I

got in jail, I first saw the lawyer. The face of a friend, finally, twenty days later! That gave me a lot of joy, so much so that lawyers asked me for the death penalty for telling me, because it didn't alter me. At the time, I only saw the face of a friend, someone worried about me. By then, the police already told us that we were not going to be delivered easily, that would happen as in previous occasions, that they would be deaths. We were told by the police and the officials in the lower camps!

And four war councils, thirteen death sentences… Although at the same time two of them were commuted. One, mine, was sentenced to 30 years in prison and the other to 25 years in prison. It was then that we realized that the police were trying to comply with what they had said in the interrogations, or what some of the officials – when they put us in the lower camps – and even what the instructions of the summits said. Despite the death sentences they suffered, they still kept our peers isolated, they didn't allow them to talk to each other, and when we tried to communicate with them, the police and the officials prevented us, threatened us not to allow them to go outside. He thought it was wrong. We did not believe that everything was going to be so fast, not even in Barcelona and Burgos the war councils, let alone the torpes and basas, which led to five people facing the peloton shooting. We didn't believe it.

How did you know your teammates were shot?

Around eight o'clock in the afternoon, around nine o'clock, we got into the field. I believe that the Council of Ministers has not yet finished [26 September]. We had no radio, no awareness that it was going to be the last night. When we left the yard the next morning, it is a real thief: comrades in the death penalty did – Manolo Chivite, Manuel Cañaveras, Vladimiro Fernandéz Tovar… – but “Ostia!”, I said, three people were missing. It was terrible. And silence. It was the morning of 27 September and there was neither Baena, nor Ramón García Sanz, nor José Luis Sánchez Bravo. So I realized.

47 years, September 27, At dawn, time to remember his colleagues...

In addition to 27 September, I remember my colleagues much more. I see them for many days, I imagine. 47 years always 27 September.

He spent two and a half years in jail. It was a scatter. Carabanchel, Cartagena and Cáceres were imprisoned until the 1977 amnesty. How did you revive your life?

Bad and very fatigued. But as the dispersion has said, we were like this, one here and another there… The dispersion, that is: Córdoba, Ocaña, Puerto Santa María, Cartagena… And there were differences! Then the amnesty law was passed in 1977 and we went out into the street. And we took the lawyer and joined the labor amnesty and tried to go back to the previous workplace, at the NCR, because the law said that if someone had been fired for political militancy, they had to go back. But the company said no, it didn't belong to me, it didn't leave me, it was me. And yes, I left, but because the police were behind! Goodbye! I fled before the police caught me!

And so, where did you work?

I had to do everything: distribute pamphlets or sell soap at home. Of all. Less bad for militancy. I was in jail, living a hard experience, and I got out of jail reinforced. And after Franco's death, the conditions of the struggle were completely different, it was easier to fight. And so we're moving forward slowly. We also had no house and we lived in the houses of our friends, one left the house and another shared it with some family. Until three or four years old, we couldn't rent our house. We live at the expense of my girlfriend's salary, barely and absent.

What about militancy?

We were party activists, and from time to time we put a house in the festival fairs, and what was there helped us. In the end, that's why I surrounded the work in a printing press and then breathed. But by then it was 1989! In the meantime, we spend many years of anguish. At the same time, the party had to reflect deeply, as the situation had changed radically and we had to rethink everything within the Marxist-Leninist movement. It was an era of intense debate. The USSR model was dissolved and, in our case, the Albanian model failed, round sugar melted like coffee with milk, it is now! On the other hand, we did not have the means, we were not effective: we worked between eight and ten hours, and we could not do much, and in 1992 the party was dissolved and everyone took their way of militancy.

You work in the Comuna association of Francoist prisoners.

Yes, I have had very diverse militancies, and since 2011 I have been in the Community. It was proposed by former president and entrepreneur Chato Galante (Madrid, 1948–2020), and almost 300 people met at a Madrid institute in the assembly. And we completed it. Among other things, we decided to join the Argentine complaint and I was also in Buenos Aires. I filed the complaint in Madrid and ratified it in 2013 before María Servini. I tried to do so in the Argentine embassy twice, but in both the Spanish Government prevented my appearance.

The Spanish Government has not provided facilities…

For all, it tries to hinder the complaint. Some wanted to file a complaint; others, ratify it, but the government said it was not included in the Spanish-Argentine agreements; in another, it argued a form error. So we decided to form a fairly large group, go to Argentina and ratify the complaint there. There I was, for example, Ascension Mendieta. Through María Servini's complaint she was able to exhume her father's remains and bury them in the Madrid civil cemetery. We have been in Buenos Aires several times…

"When we left jail, we didn't even have a house, and we live in our friends' houses, one left the house and another shared it with some family. Up to three or four years we couldn't rent our house."

More than once?

Yes, and we have achieved something every time. I told him Mendieta's, but before that woman's, we managed to cause [Jesus] Dolls [Aguilar] Police, and Antonio López Pacheco, hard policemen and torturers. In our case, in 2013, we prosecuted 20 high offices of the dictatorship: Martín Villa, Fernando Suarez and the Auditing Judge of our War Council, Jesús César Mohedano, among others. They are all charged, for example. And that is what we are, after so many fights, in the struggle, in which all freedoms, fighting, blood and murder have been achieved. We have achieved some things, others not, such as the right of peoples to self-determination.

They say the path is struggle.

There is no more. A lot is happening. There is war, inflation, repression in Catalonia, repression throughout the Spanish State, against puppeteers and against singers… Also in that, of course, and with it, we are also bearing witness, to face the impunity of Francoism over and over again, which would air democracy in the Spanish State. This putrefaction from the sewers of the State and the dictatorship does not allow us to arrive at a logical situation. That’s the word, logic…

Logical?

Yes, then. There's the government, making 40,000 people stand upright, putting a whole country upside down, saying that you don't turn on the light from the windows of the store, that you don't shower, that you save energy -- and you're not able to run a band of putasemes to make sense of those who are spending too much. It is illogical! They are able to put 40 billion Spaniards in trouble and are unable to face a hundred human beings! And meanwhile, they are manipulating the prices of money, gas and electricity. And meanwhile [Ignacio] Galán [president of Iberdrola], earning 13 million euros a year. What is this? Where do we live? It is not logical, it is not normal, it is neither logical nor normal for the impunity of Franco.

"And in that we are, after so many fights, in the struggle, in which all freedoms, fighting, blood and murder have been achieved. We have achieved some things, others not: the right of peoples to self-determination, for example."

Logical, illogical. Txiki and Otaegi are recognised victims at the CAPV. Meanwhile, Sánchez Bravo, Baena and García Sanz do not, in the Spanish state.

In the Basque Country they have more political awareness. Also in Catalonia. For example, a law of the Catalan parliament rejected all the judgments and war councils that existed there during the Franco regime. Puig Antichena and Txiki intervene. In the Spanish state we are in it, pending the law of Historical Memory, to annul all the war councils of the time. We will soon know what they accept. Meanwhile, and in my case, see and believe!

You're not fixed.

You can't trust it. Our problem is that Franco had a great force in Madrid, and always wants to maintain that force: the economic, the military, the police, the judicial… of all kinds. It is a force imposed with great fear, because the repression in Madrid was a genuine barbarism. And in demonstrations, strikes, controls, torture, etc. The deaths in the SMI and in jail have been unlimited. And today, it's a demonstration, and there are young people who have had to spend a year in prison. Or they have received abusive monetary fines, which are obviously dissuasive fines. A young man is murdered with a fine of EUR 600. Or if you have three days in the police station, you lose your job. Repression is particularly harsh in Madrid.

“Our party

had many militants. We were not the only ones. There were PT, ORT, Communist League… We were out of the pacts and reconciliation of the PCE or the PSOE. The conversion of the PSOE was the work of the secret services of the dictatorship, making it an instrument of the dictatorship. It was said that the PSOE of Carrero Blanco was in the hands of the secret services. Felipe González and Cops attended the congress held in Suresnes, France. It was an orchestrated maneuver."

MARTIN VILLA

“And we must catch Martin Villa and take him to the judge and ask: 'What promised on September 27, 1975 when they were going to fuse Juan Paredes Manot? '. Because Martín Villa gave orders because he was the civil governor of Barcelona. It instructed the police and the Civil Guard and each other to authorize this assault. And that's a complicity murder. That’s what we want, take him to Judge Martín Villa and defend himself.”

LAST WORD

“They have

collected testimonies of the war, through relatives and archival documents. Ours is a direct, living testimony. I was tortured, massacred, judged on the war council, without any guarantee. I was sentenced for 30 years for the dictatorship! And my friends were killed! It is necessary to alienate our testimony, and hence our militancy towards memory.”

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

Bilbo, 1954. Hiriko Alfer eta Gaizkileen Auzitegia homosexualen aurka jazartzen hasi zen, erregimen frankistak izen bereko legea (Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, 1933) espresuki horretarako egokitu ondoren. Frankismoak homosexualen aurka egiten zuen lehenago ere, eta 1970ean legea... [+]

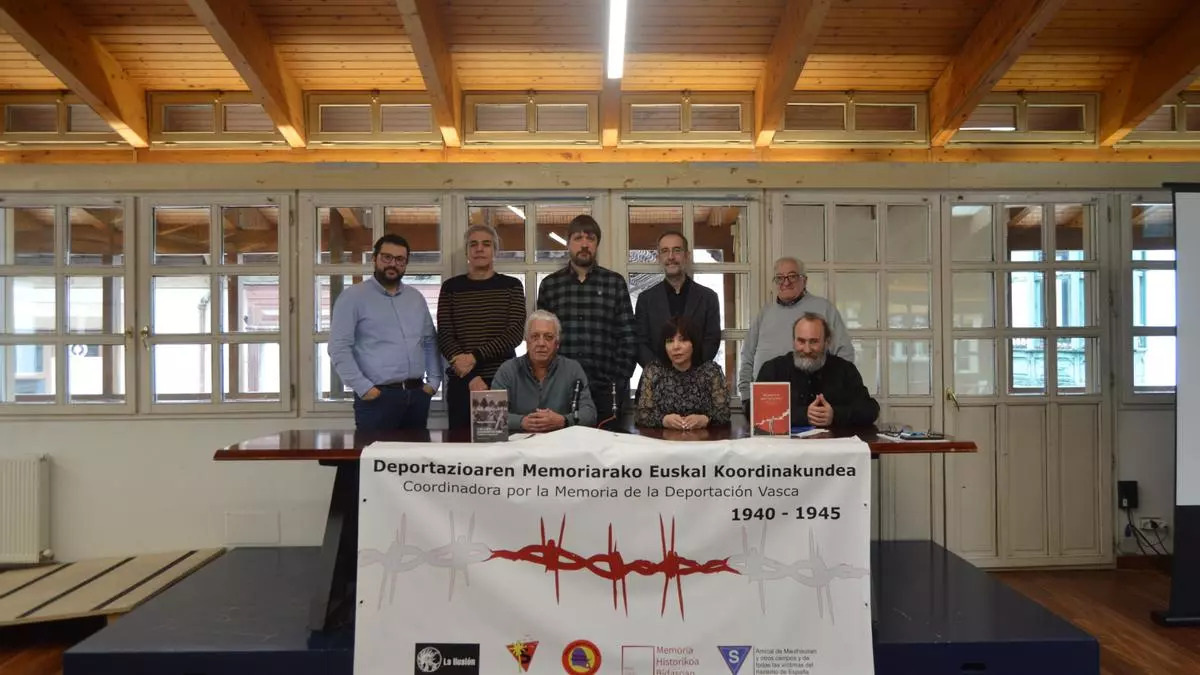

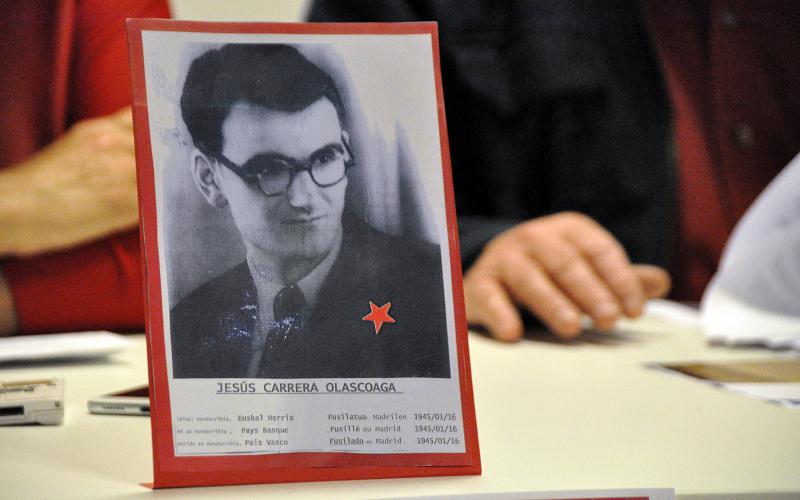

Deportazioaren Memoriarako Euskal Koordinakundeak aintzat hartu nahi ditu Hego Euskal Herrian jaio eta bizi ziren, eta 1940tik 1945era Bigarren Mundu Gerra zela eta deportazioa pairatu zuten herritarrak. Anton Gandarias Lekuona izango da haren lehendakaria, 1945ean naziek... [+]

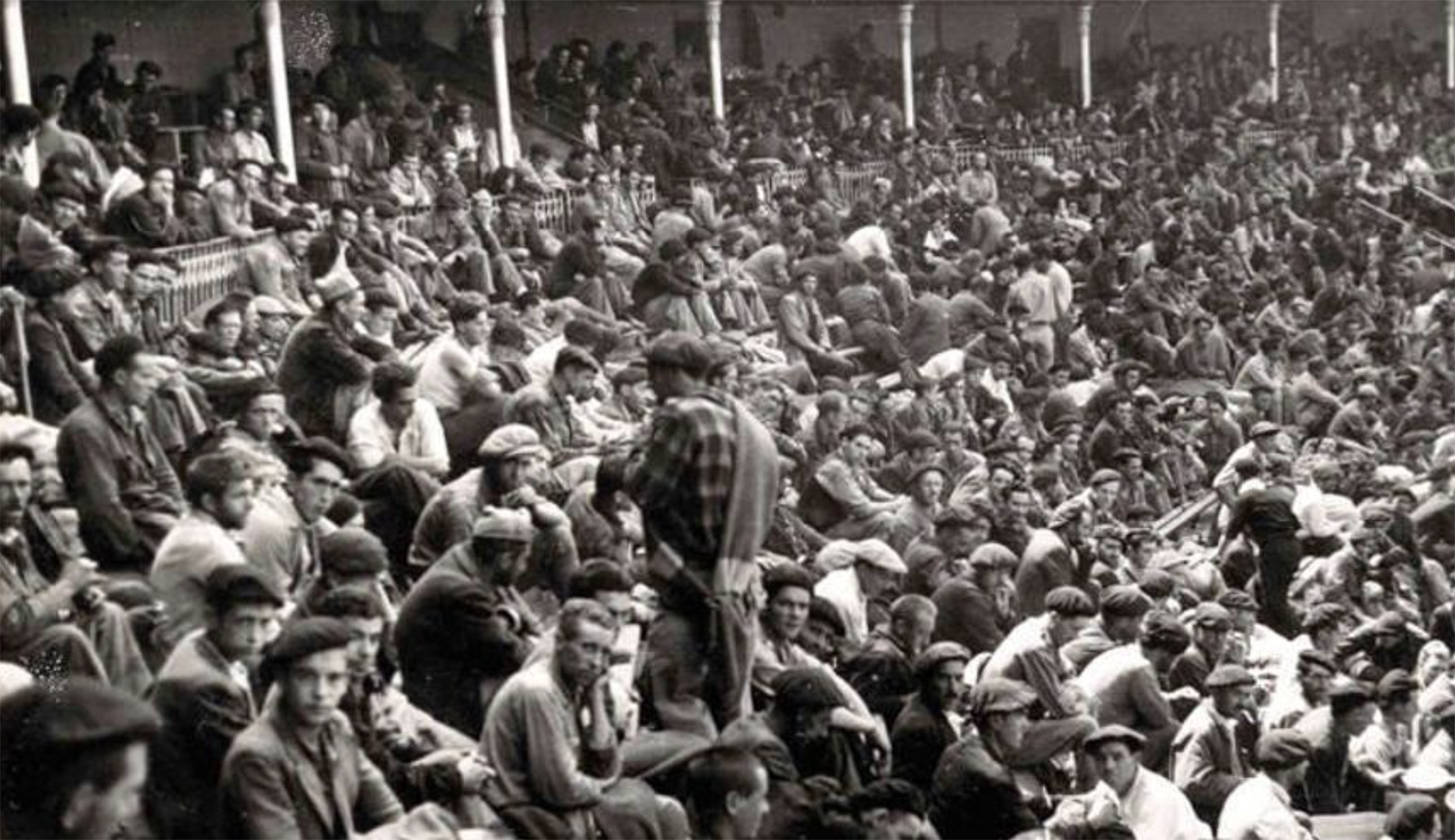

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]