"Monuments are not history, they are an interested version of the powerful, only advertising"

- Peio H. Riaño (1975, Madrid) is an art historian and journalist. He has worked in various newspapers and magazines, among which he has been the editor of Public Culture. You will now find your signature in elDiario.es. He has also written several books and we have joined in the thread of one of them: Beheaded. Following the assassination of George Floyd, this work was published in 2021 by protests over the racism of public institutions. It is one of the few works written in Spain about myths and heroes that the power of the time imposes on public space as a state.

It seems easy to look at the past from the present. But it's a cultural struggle that's long since.

Yes, for a long time I've been investigating the view of the current citizen about the history of art. This sense requires a political attitude, and that is why art historiography has avoided it. Every work of art is the result of a political, economic and social context, but historiography has wanted to isolate works by turning them into plastic facts beyond their time. This has led to contradictions and exclusions. The most important thing is the exclusion of women.

The streets are full of military, priests, bishops, virgins, slaves, conquerors, wealthy entrepreneurs, professional politicians… Almost all men, all white, all of them related to the elite of the time.

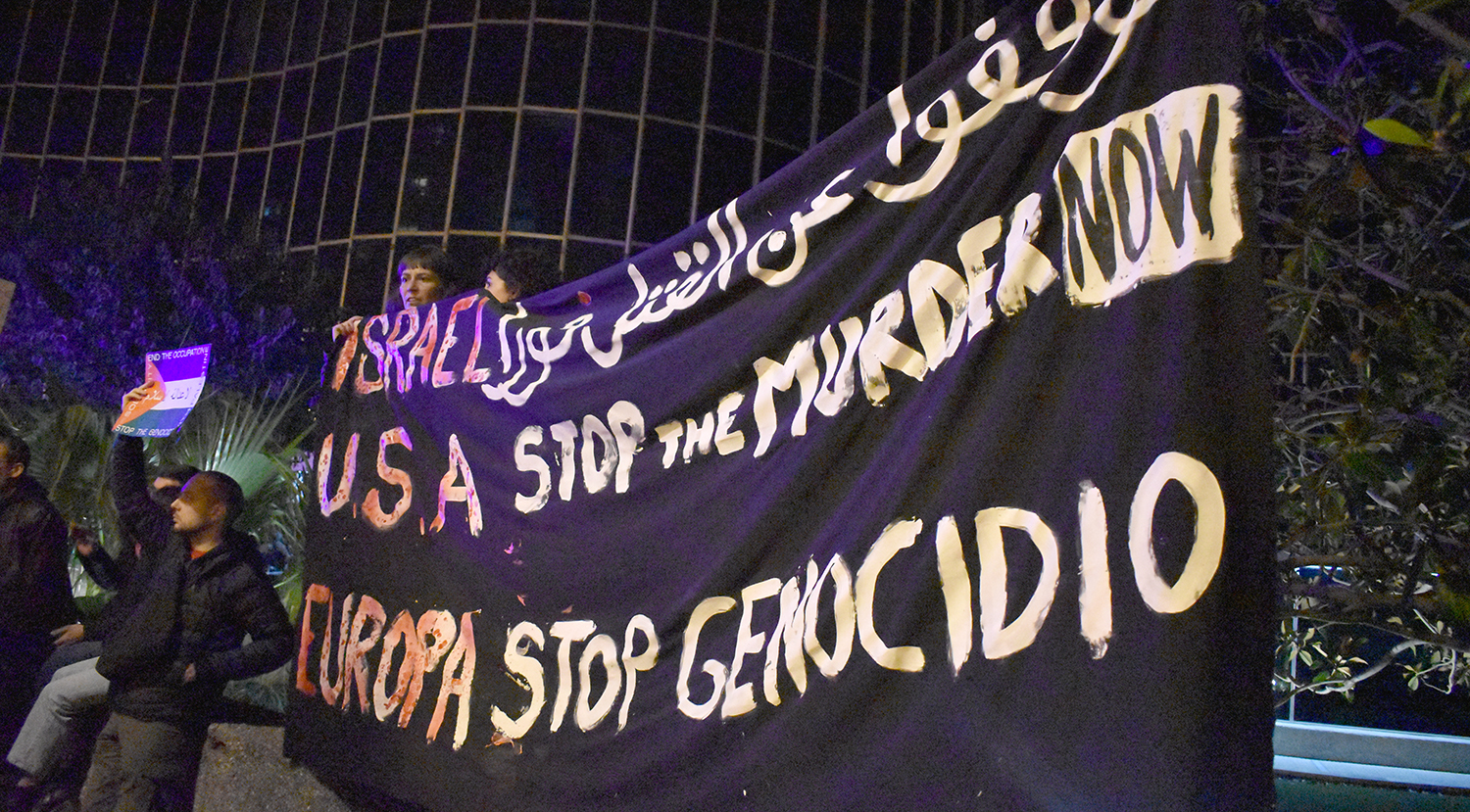

When the power decides to place a monument in public space, generally honoured as a man, it is related to the interests of the authorities, not to the wishes of the citizens. What I am proposing is that future generations, we, heirs to those times, have all the legitimacy to go against the macabre inheritances we have received. It is time to say that it is enough. Since the end of the 19th century, we have been living among those ads that have brought us in as statues; surprisingly, until now we have not been able to get them out of our streets. We have nothing to do with them anymore. These statues don't represent us. And yet, we have to live with slaves, dictators, powerful people who don't represent most of the social, political and economic ideas and values we have today.

What was imposed without asking, should it be withdrawn without asking for permission? Or, in other words, where does the legitimacy of removing a monument, a state or a street from public space arise?

I do not know why, perhaps especially with the fear that the far right will be annulating (he uses cancellative) or politically correct, we have not dared to take those misunderstandings out of our streets. When something is built in public space without the legitimacy of the citizens, there is no guarantee that the citizens will respect it. One generation can respect it, but the next one can say it has nothing to do with it. This is the basis of the extinction of monuments.

In Madrid, for example, we will live something very curious. The City Hall has approved the installation of a memorial to the legionaries, without knowing the signing of the members of the municipal commission of landscape and monuments. In principle they had to place it in Plaza Oriente, where fascism is concentrated. Thanks to their hustle, they decided to settle in another ‘violent’ place: Facing the constitutional monument. They say it is a tribute to the origin of the Legion, and thus try to avoid what caused the Civil War: the Legion which was the most bloody group. It is the statue of an armed soldier, such as those who exterminated in the war, such as those who invaded the Spanish state. I do not believe that the symbol representing the Community of Madrid in 2022 is a weapon. I do not know, but I doubt it.

This monument will explain in the future how Madrid ruled in 2022. And then we will know that José Luis Martínez Almeida, along with his colleagues from Vox and Citizens, decided to pay tribute to death and war on the streets of Madrid in the midst of a war.

Is every monument a political whim?

Monuments are history? No, of course. Those who believe that part of the story is being wiped out when a monument is thrown out, what do they want to get? They want to justify this withdrawal through a false debate, because it is propaganda, not history. History will continue to be written, analyzed, documented and published by historians. Every monument is an announcement, an interested version of the event that pays tribute. It's a postcard for a given moment, but it's not history, let alone!

While states linked to colonialism or slavery were being withdrawn in several countries of the world, silence was imposed in the Spanish State, as if the issue were unrelated to us. What about this? The citizens'

manifest lack of sovereignty, especially on the right. And that has a direct reflection on these kinds of issues. Spain or its powerful part has complexes in this matter. For example, with the advent of democracy, they decided that the day of the Spanish national holiday would be on October 12 and would celebrate the “discovery of America”. It was therefore resolved that what had to be honoured was a patriotic issue based on arrival on another continent. Far from what Spanish nationalists want us to believe, the symbolic idea of the Spanish State is based on another continent. In other words, Spain itself is not. Spain exists after “finding” another continent. Through 12 October we are told that Spain would not exist without America.

I find it very ridiculous as a symbol, because if you want to be proud of Spain, you have failed. And from there, everything that questions the false myths built at the end of the 19th century, when Spain starts to “lose” all the colonies. In that century a reactionary movement emerged that made citizens proud of a past that will never return. From this imperial nostalgia comes the legend of the great conquerors, which we continue to defend today.

And today we've come to that delicate image of Elcano. The same figure is defended by Basque nationalism on the left or right and by Spanish nationalism. It is a very grotesque matter, because, reading the researches of the specialists, you notice that what happened on that Elcano trip is a series of casualties and disasters. The myth comes much later and is also poorly cooked, as if it were half-hearted. The myth is accompanied by heroism, tributes and literature.

I think it is very good to celebrate historical facts, but to create a sense of attachment, to build a political legend … you have to look at them from the distance and question them. It can be celebrated that one man, along with others, returns to the port after an erratic and tragic journey, but what interests me is to see how our community is going to work this myth. In the end, these celebrations define you as a society. We citizens should look away and critically at the symbols and events of the past, as well as those coming to rebuild a mystified figure now.

All these kinds of commemorative events and hundreds of events seem to be impossible to organize without ending up looking at the navel. It seems impossible to remember a historical fact, what we “were” without focusing, our feats, the first, that the best “were”… I am in favor of memories to remember the

past, as long as the discourse is directed by historians. With data, with facts, with context – cause, consequences, victims… – but if we stay in building a novel, we are making politics.

Yes, but there is also debate among historians. From the same data or historical document, very different discourses can be produced.

Yes, history is not unique. But I at least prefer the debate to be between historians. Serious debate based on sources, documents and facts rather than opinions. I prefer that debate to debates of bad taste. Symbols built by nationalism are curved because they invite feelings. The only thing that interests me about monuments is the portrait of the moment they are built or celebrated. Once we know they're interested milestones, we're going to question what they do there. Someone put Edward Colston in Bristol, another Franco in Spanish cities... They have to be removed, sent to museums, contextualized and historians will explain why they moved, why they removed that symbol from the street. Nothing else. They're not history. They are part of the story that happened a few centuries after the events that they pay tribute.

It is a very mandated argument that one cannot look critically at the past with the eyes of the present because it was “another time”. They call it presenteeism. Presenteeism is very curious

because it only applies “this figure does not replace us” or “we do not want exclusive attitudes of the victims of the invasion in the street”. It does not apply, for example, to the memorial. Meanwhile, Peru retains a monument of Christopher Columbus at the end of the 19th century. In it appears Columbus arriving to America, grabbing a woman on the ground, representing the indigenous population – even if it is a Western face, because the sculpture was made in Italy. The woman asks Columbus for compassion and evangelization, while the conqueror offers him one hand and the other lifts a cross. This monument is an interested look at an event that occurred four centuries earlier, but they don't call it presenteeism.

Anyone who flaps the flag of presenteeism wants to silence critical voices, but does not want to ask us questions about our past. I prefer, as a Spaniard, to claim the victims of the “discovery”, of the invasion. As a Spaniard I do not feel identified with the military part, I feel closer to the survivors of that massacre. And I want these people to be proclaimed today, not those Spanish soldiers who destroyed the people of origin and the citizens.

Assassinations, slavery, conquest, torture, rape, homophobia -- they are “abuses of the past,” because then “the whole society was like that too.”

That is the basis of presenteeism. Context is important to understand what happened, but not to justify the facts. On the contrary, history has the function of documenting, analyzing documents and transmitting the conclusions of the work to their society, with the terms, expressions and dictionaries used by the society of the time, with all the ideological backpack of society. It makes no sense to write about the history of the American invasion in a 15th-century castle for the people of the 21st century. Among other things, because these facts have to be counted from the present. Genocide has no justification, but part of historiography has endeavoured to justify it in the name of the adventurous ambition of the Extremadura military, such as Hernán Cortés.

For in the midst of an invasion there were massacres, we must count it and say it accordingly: genocide. For such events, we must use the word we have expressly created. The same is true of works of art. For example, if a painting depicts how a man kills a woman who has just denied “love,” can we not say that it is feminicide because the painting is renaissance? Of course, yes, because that is the same thing. We, as a sovereign society, can explain what happened on our own terms. If we do not want to repeat the same facts again, we have to tell from our perspective what happened, not from the perspective of 1492, for example.

History is developing not only with the new discoveries of documents, but also with how to tell them.

It seems that there is a

great distance between the decolonal anti-racism discourse used by the movements of migrated people and the speeches of political parties or the left institucional.Es truth that the political class does not have the message of a part of society against racism, is further behind. Because Spain was a slave industry, which seems to us not to accept. Imagine, Velázquez also had his slave. There's not enough research about our enlightened past, that past we don't want to look at. This has helped to create today's racist society. It is a taboo subject. We do not want to arrive, even if it is a state that lives with migrants, that needs migrants, that we need. We continue to ignore it, we let it pass, but this indifference is being strengthened by the racist, the extreme right, and the hate speech against the different.

All people have their myths, symbols, references… to make them feel part of the community. But consensus on these issues seems almost impossible.

Of course. The historian must live this conflict in a healthy way, aware that his work will generate “truth”. All this is conflict. Conflict is against comfort.

In short, a tribute to the person concerned, what is really emerging is a conflict. This must be understood and resolved in the light of this. I do not deny monuments, their imposition is what must be denied. .

Joan den urte hondarrean atera da L'affaire Ange Soleil, le dépeceur d'Aubervilliers (Ange Soleil afera, Aubervilliers-ko puskatzailea) eleberria, Christelle Lozère-k idatzia. Lozère da artearen historiako irakasle bakarra Antilletako... [+]

Despite the black skin and curly hair, they remained invincible men, with the intelligence and resentment of human beings.” So he wrote about the slaves CRL James in the book Jakobino Beltzak, who masterfully narrates the Haitian revolution. So many brutalities, torture and... [+]

Malin, Burkina Fason eta Nigerren Frantzia haizatua da. Mendebaldeko potentziek haien eragina galtzen ari dira Afrikako kolonia zaharretan. Afrika frankofonoko populazioa bereziki gaztea da, eta ez du frantses kolonialismoa zuzenki ezagutu. 35 urtez peko gazteek populazioaren... [+]

Last week I was at the Olaso Tower in Bergara, in a talk about symbol acquisition.

Behind the symbols there is a story, and it is evident that the symbols we have before us – shields, flags, monoliths, street names… – tell the story that suits the empire.

It is not in... [+]

II. Following the World War, the process of decolonization of the countries of Africa and Asia began. In fact, the soldiers of these countries participated in the triumph of Germany and its fascist allies, and “as a thank you” those subordinate countries had to be recognized... [+]

In the bar Gato de Pamplona was singing screaming, the famous song of curse of Malinche: "Eta oker horretan, pasako grandeza eman egingo dugu, eta oker ants three hundred years Geratu gara slaves."

Having a birth in South America, especially in Colombia, is nothing comfortable,... [+]