Tantric journey from mourning

- Her mother died in a few months at Irati Gorostidi (Egüés Valley, 1988) and at Mirari Echavarri (Pamplona, 1988), both passed by the Tantric community Arco Iris, stabilized at Lizaso in 1978. If they were already interested in this experience, everything accelerated in the grieving process. San Simón 62 takes the form of this search, premiered this year at the Punto de Vista festival of Pamplona: two daughters dialoguing with their mothers, among them spirituality, community life, nonexistential, gender, sexuality or the search for freedom, in the Navarra of the early 80's.

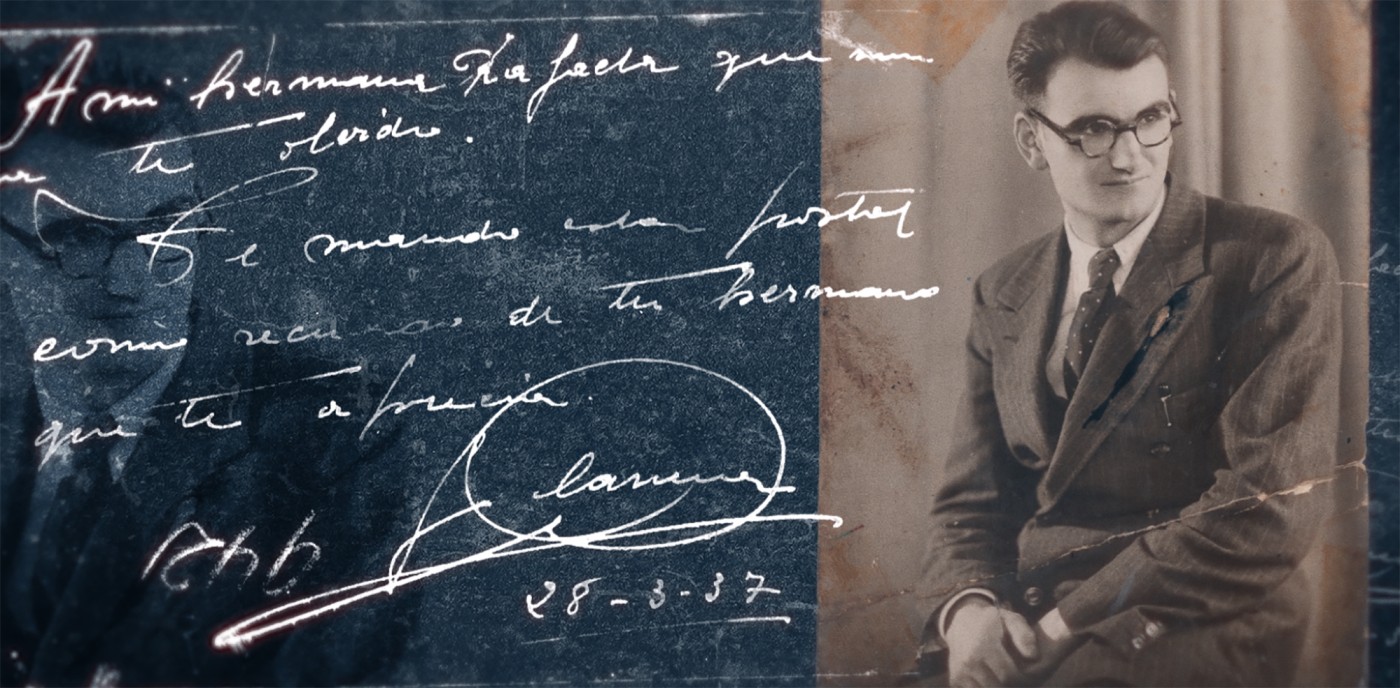

Even though their parents have been there, the Rainbow community was known as a child by Irati Gorostidi and Mirari Echavarri, but they recently began to discover what it really was. In common. His father handed Gorostidi a photo book there and beat him at the time. He sent them immediately to Echavarri. He also started the search and found a number of publications in his parents'. These were journals created in the community itself, with their own photographs and promotional sheets of the courses, which were the main source of income. Then, when the mothers of both died in a few months, the curiosity was heightened: “Something happens when you approach the mother’s age when she was born: you feel very connected to her and some conversations start,” says Gorostidi. In the process of mourning, in full thirst to know everything about the mother, the two joined together and from there comes the film San Simón 62, premiered this year at the Punto de Vista festival in Pamplona, whose name flashes the direction of the convent in which Arco Iris stabilized.

Even after the film they find it hard to explain what Rainbow was. Gorostidi says that they also feel a kind of reticence, as in addition to his film, there is little in the network about that community: “We seem to be responsible for defining what that was. After the movie, two or three people have written to me saying that their parents have been there, and because they don't know very well what it was, to see if I can explain it. And it's very difficult, of course. Our sources of research have been correct: their publications, the testimonies of the participants… I can imagine, but I feel that I still do not understand what it was.” After being founded in the late 1970s, they lived for several years in Lizaso (Navarra), before traveling to Catalonia (Arenys de Muntera and Alcover). “They initially defined it as a tantric community, but they soon assimilated other trends. It had an aesthetic and iconography very similar to that of the communities around Osho. The singularity is that in 1978 something like this can be imagined in Navarra,” says Gorosti. Although tantra is very important, they had other effects. “At first the issue of sexual liberation was fundamental. Besides people close to the spiritual leader, there were also people who lived there and attended only courses. The courses attracted so many people, because the community grew very large, and soon opened two new branches in Catalonia.”

.jpg)

Directors make a radical choice in the film: they don’t even talk about spiritual leader Emilio Faithful “Miyo”. They were clear from the beginning that they didn't want to make the story of a group built around a leader, but they doubted at least whether they had to be interviewed or not. Gorostidi explains that during assembly they decided not to: “It pushed us back and that’s significant. In everything we have received about Arco Iris, it was so important… It is not that what happens around a guru like this does not matter to us – from a gender perspective, for example, it can be very interesting – but we have wanted to give way to other stories”. Echavarri defines that these stories are close to their own interests: “We approached Arco Iris according to our mothers’ footprints, and therefore we already saw what the themes could be that move us: motherhood, sexuality, childbirth, childcare, relations between men and women… all of a sudden we realized they all had a relationship.” They even realized that some issues become especially problematic if they are reproduced by a community that theoretically seeks freedom: “They tried to put everything upside down, in a very simple way, without taking into account many fundamental aspects,” explains Gorostidi. “We have spent forty years in Franco, we have been educated in Catholicism and now, from morning to night, we are able to overcome it. And in addition, and a foreign tendency, the tank from Hinduism, will solve our deeply rooted spiritual and sexual problems... It seems to me very hard.” Echavarri finds it similar: “This immaterial spirituality clashed with very material issues because it was a privileged male spirituality.” Despite tantra, women became pregnant and then left the group. This shock is the one that most interests Gorostidi from that experience: “Talking about sexual liberation is very problematic without considering the gender perspective. Today, when we see how some things were done, there are many doubts.”

No idealization, no easy sentence

Despite the criticism, directors talk about the film wanting to value that experience. “Many times I realize it’s very easy to see the attitude from a judge, as if it were a cult. At the same time, it is easy to fall into cynicism. We have tried to avoid them,” explains Gorostidi. “Also romanticism,” adds Echavarri: “Some who lived it remember a kind of idealization. But then those same people remember very hard experiences. Imagine how complex it is.”

.jpg)

When they were looking for a way to approach this experience in a balanced way, they decided to get into the film. It was somehow a way to escape the logic of orthodox reporting. “You can take a long distance from what you’re recording, trying to reconstruct what happened with very diverse voices. Our commitment has been precisely the opposite: the voices we have chosen are very partial, we have had a direct relationship with these people, we are also involved, and we count from an intimate perspective what interests us in this experience”, says Gorostidi. They didn't have that choice very well; when they solved the mothers' grief, they decided to make the two.

Another important formal decision was to record everything with a 16-millimeter Bolex camera without batteries, to complicate the process. They could record planes up to half a minute because then it was cut off. They are aware that 16-millimeter cameras can be embellishing devices, but they find another sense because they are interested in adapting to the conditions imposed by technology. According to Gorostidi, using this type of camera from a superficial perspective does not make much sense: “There are simpler ways to beautify the blueprints. Working with these kinds of cameras is very expensive and expensive. And it also greatly affects sound making. The camera is so loud that it is heard at all times.” During filming, they realized they couldn't sync the sound to the image because of the camera's special features. This completely conditions the latest version of the film.

Working with this special camera has served Echavarri to get away from what they were doing: “Digital technology is highly interiorized in everyday life. On the contrary, such a difficult technology helps you to take another view, if it is an intimate and emotionally heavy subject like ours. Staging has to think much more.” Gorostidi joins: “Between what you record and what you don’t have, a big border emerges. With digital comes a fantasy, which is not true, that looks like you don't have to make big decisions when recording, because in case you can record everything. With the analogue, instead, you have to decide a lot of things in the shoot.”

.jpg)

The possibility of continuing

Gorostidi and Echavarri are childhood friends, but after many years without knowing each other, they found themselves in the Fine Arts class of Bilbao. For many collaborative classroom work, this is the first film directed together. Gorostidi presented the project to the X Films competition of the Punto de Vista Festival and later joined the Echavarri process: “When I entered there were many things defined, but in the shooting we have improvised a lot. It has been new to me to work this way, making decisions at the moment. Hit someone's door and see what happened. It has taught me to trust the process.”

Many of those who have seen the film have told them that they have been hungry. Although they have no concrete intention at the moment, they are eager to continue with the project in some way. “We had a lot of ideas, but it didn’t give us time for more.” In any case, Gorostidi at least intends to continue with the accounts of the Rainbow community. He writes a fictional feature film called Anekumen, set in his experiences: “It first occurred to me to address this issue from fiction, but it does so… The short one I just finished is like the first part of that feature film. The protagonists of the film make a journey: they come from the labor movement, where all these revolutionary concerns are awakened and enter Arco Iris. It was the trajectory of many people, both the parents of Mirari and my own. During the transition they are captured by disappointment and a huge vacuum. They get into a kind of existential crisis, they find no sense at all and try to find it in those places. That’s the theme of the project I’m writing.”

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.

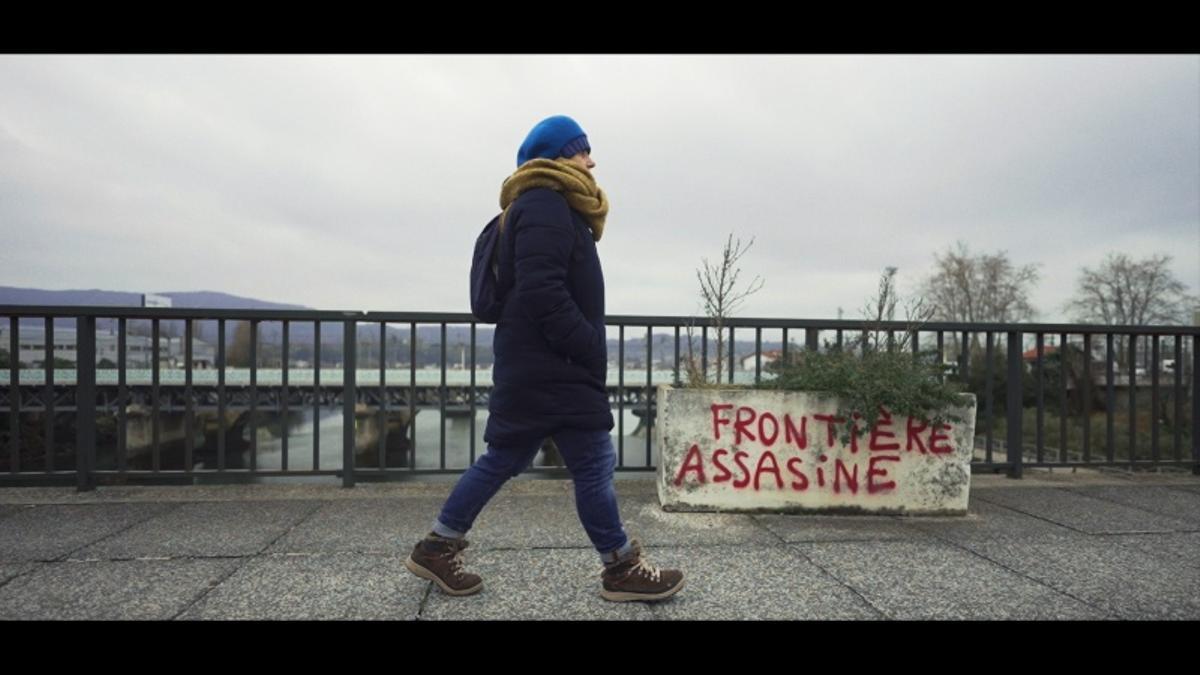

Projection of the documentary Bidasoa 2018-2023

Where: Martutene prison, Donostia

When: Friday, 22 December, 16:00h

Available as a network: Perfect on the platform

------------------------------------------------

It's Christmas. Friday after lunch. Let us go through the long... [+]

FIPADOC Nazioarteko dokumental jaialdia berriz heldu da Miarritzera. Urtarrilaren 19tik 27ra ospatuko dute, eta seigarren edizio honetan «Italia eta Afrika» izanen dira protagonistak.

Hands have a varied symbology. With hands the world is driven and with strong fists the command is supported. Power also fights with fists, picking fingers and raising hands up. Hands are necessary for those who have always been the losers of life, for that alone has been an... [+]

Lana finantzatzeko diru bilketa abiatu dute; ahalik eta gehien zabaldu nahi dute ikus-entzunezkoa, protagonistak sufritutakoa ezagutarazteko eta torturak salatzeko. Bi arnas kontatzen dira, torturaren eraginez itxi gabe dauden bi zauri: Sorzabalena eta haren ama Maria Nieves... [+]

Mikel Zabalzari buruzko Non dago Mikel? filmak Urugaiko Nazioarteko Zine dokumentalaren festibalaren sari nagusia irabazi du, AtlantiDoc Saria hain zuzen ere, dokumentu-film luzerik onenarentzat.