Yayo Herrero. Raw and hopeful

- Two years ago I first heard a lecture by Yayo Herrero at the Feministaldia festival, and since then I have not been able to forget their demanding questions and reflections. Herrero is an engineer, an anthropologist and a professor, and his battlefield is ecofeminism. He knows that we are facing a multidimensional crisis as a society and that is why he claims everyday utopias.

Ikasketaz, antropologo soziala, nekazaritza ingeniaria eta gizarte-hezitzailea da Yayo Herrero, baina aktibismoari tinko lotuta egin du bidea. Ekologistak Martxan erakundeko koordinatzailea izan da –bertako kidea da oraindik–, eta hezkuntza ekosoziala bultzatzen duen FUHEM fundazioaren presidentea ere bai. Hainbat liburu eta artikulu argitaratu ditu ekofeminismoaren eta ekologismo sozialaren inguruan, hala taldean nola bakarka.

You have a very long trajectory in ecofeminist activism, but looking back, remember when you became aware of the issue?

I remember very well. From very young, from the age of 14. I started with international solidarity and then trade unionism. Even though it's a alley, I've always had a close relationship with nature. I was studying engineering in a chicken coop. I saw it clear, if we had to do things like this to eat, that something was wrong. That was my ecologist awakening, and soon I went to social environmentalism from previous experience. When I worked at Ekologistak Martxan, I read an article by Cristina Carrasco, Ana Bosch and Elena Grau, who combined ecologism and feminism, which somehow linked everything and gave me a different worldview. There I first heard the concept of sustainability of life.

You have come to Donostia with the excuse of the first International Congress of Feminist Anthropology [we met on

June 10].As for the approach of the congress, I love its relationship with social movements and with society itself. I think that is essential. The area of knowledge and research being worked on in this congress has the will to transform. And that's very important.

Specifically, a round table will discuss the relationships between feminist anthropology, feminism and society.

I've never been in a feminist group of women, I'm a member of the environmental movement, and I'm a feminist activist in that movement, of course, but in our movement we're not just women and we're not feminist people. My organization is considered a feminist in its ideological principles, but that doesn't mean that we've freed ourselves from patriarchal dynamics, or that we're all aware of them. We have a long way to go. From that position I will speak.

And in that sense, what challenges do you see in the environmental movement?

I think we have to review the subject, that is, what the human being is, and I think we have to overcome a series of dynamics: trends in our culture to look at the earth and bodies from the outside, from superiority and from instrumentalization. Furthermore, I believe that feminism and the anthropological view can be of great help in looking at a somewhat mature vision of collapse and ecological crisis, and connecting what we call multidimensional collapse or crisis with everyday life, bodies and discomfort. This place offers more possibilities of social mobilization, it is more hopeful than that other vision of collapse that comes to him and does not know what to do with him.

.jpg)

"We have to imagine life from the beginning of sufficiency: learning to live enough, from

law and duty"

What about the pandemic and post-pandemic alluding to collapse?

The pandemic, especially at first, gave us a moment of clarity, of seeing things that are usually hard to see. For example, the enormous fragility of economic metabolism was highlighted. It also gave rise to some debates – I mean among people – such as basic jobs, and basic jobs, which are often done by women and are poorly paid. On the other hand, and I repeat this time and again, because I think it is very important, there was a Community explosion. In a very harsh situation, many people advanced one step and proved willing to care for others. And that brings another idea: if people really knew the situation, at least an important part of society would be willing to significantly change their way of life so that they, loved ones and, consequently, society in general, would have good lives.

The pandemic has also left cause for concern.

We have seen dangerous speeches. For example, some of these militarized discourses, which refer to the concentration of all against the enemy, are problematic, since similar discourses are used against migrants, dissidents or women. On the other hand, the consideration of the elderly as surpluses is terrible, I found it terrible how, in some public services, vulnerable people are considered raw material for the business. And that spying on neighbors also seemed very serious to me. In short, we are experiencing a polarization: Will we move forward by supporting, assisting and organizing ourselves, or by creating a common enemy and delegating the management of problems to the state and the security forces? I believe that the two currents were present in the pandemic and reflect the tension we live today.

The pandemic relaxes, but despite everything, we are in a serious situation. He is in favour of counting and explaining this without hesitation. The

severity of the disease has diminished and health systems are no longer in crisis, but we have a huge energy and material problem: local supply chains are broken and food supply is currently being reduced and regulated in many countries. It is very likely that in a few months there will be a food crisis due to the increase in the price of food, and I find it very serious that nothing is done about it.

So, first of all, I think it is essential that most people make every effort to understand what our concrete situation is. I find it impossible to imagine another model that protects people's living conditions, if people don't know what situation we're in. That is why I am a strong protector of showing reality in its crudety. And from there, start imagining desirable lives that correspond to the physical limits of the planet.

What kind of life would it be?

We must represent life from the principle of sufficiency. Learn to live with sufficiency, law and duty. Because there are those who do not have and have to have enough, and others have more to do with us – I am constantly referring to the material aspect – and we have to deal with deceleration, sharing wealth and taking the common and good life as a compass, both in public policies and in daily life.

Given the depletion of fossil fuels, it is clear that we will have to learn to live with less. However, the idea of growth continues to generate rejection.

I do not agree with the idea of slowing down as a political proposal. Degrowth is not a political proposal, it is our context. Our socio-economic system will suffer a material decline due to the lack of resources to continue to grow. It is compulsory. And this can happen in two ways: right or wrong. If we do it badly, we will see fascism and ecofeminism. Well, we'll have to learn to live with less, in global terms, because there are those who don't have enough to live right now.

In addition, a decline is taking place: the one who has taken away the light because he could not pay the bill, is in a crumbling state, who eats food of poorer quality, as are those who take home. And in other countries, people's lives have been down long ago.

.jpg)

"It's happened to me, too. And that is the grief: the grief to recognize that the material progress that has been sold to us is impossible.”

Why do we find it so hard to accept

this diagnosis?In our culture, the idea of progress has been associated with material and economic growth, so the decline is considered a sign of delay. On the one hand, that element is there. In this regard, given the importance of the idea of progress in our society and, on the other hand, that technology has promised us that it will solve everything, I fully understand that suddenly people feel very unhappy when they realise the situation. It happened to me, too. And that is the grief to recognize that the material progress that has been sold to us is impossible.

Let me give you another example: go to the doctor and tell you that you have cancer. It is a great disgust. You go to a couple of doctors to let them know, and once you've recognized that you really have cancer, you target everything to that healing goal. And all of a sudden, a lot of things lose importance, and the important thing is to complete them. Well, here it is. Once you've approved the diagnosis and understood where we are, you want to look to the future, to see what you and others can do to be able to face the present and the future with the will.

I ask you about a couple of projects in which you are involved. On the one hand, he is a founding partner of the Garúa cooperative. What is it and what do you do?

About fifteen years ago we created four members. We shared activism and had a very similar perspective in the educational field. We wanted to create a project within the transformative social economy network to develop our profession. We are then met by other members and today we are thirteen. As I said, we started with education, but today we help to channel eco-social transitions, with a feminist perspective. We offer advisory services, research, training and support for the implementation or development of projects in this area. We also worked on projects related to agroecology such as the integration of agroecological food into school canteens.

On its web it gives a lot of importance to relatos.Nos it

seems necessary to change the worldview and create other narratives and explanations to understand the moment we live. We work with museums and cultural institutions because we believe that other languages – fiction, poetry, art – serve to communicate all the issues that concern us, through the body.

On the other hand, you are the spokesperson for the Transition Forum. What is it? That

said, it can give some pride, but we want to be a small think tank to try to influence decision-making and power spaces, like institutions, companies and social movements. But the first thing we want is to focus on these issues. We have a collection of publications, and for example, we have analyzed the consequences of changes in cities. We have recently produced a report on the real impact on the sustainability of public policies announced by the European Union and the Spanish State. And from there we try to influence politically in municipalities, in state policy, in universities or in companies.

"This urban dynamic is also occurring in rural areas. A serious rural concentration is taking place which I regard as very dangerous"

We are in the center of San Sebastian, the summer starts in fifteen days, and I would like to ask you about a subject you have not worked directly: the tourist.

It's terrible, it's happening in every city. The wildest case I have ever known is Barcelona, with the arrival of the cruises. But in the last three years that I lived in Madrid, the change was huge. It is very problematic, on the one hand, how the load capacities of a territory are exceeded, and on the other, the gentrification processes that occur with it, the expulsion of people from their neighborhood, the price of housing is greatly increased, huge inequalities occur, and the city is no longer a place to live in the community. Cities become theme parks serving tourism. In addition, given the rise in oil, the survival of the city is seriously affected, as the city and its economic life, the lives of its inhabitants, are ultimately directed at the service of tourism. This dynamic is occurring, at least in part, in rural areas. A serious rural concentration is taking place which I regard as very dangerous. Besides all that said, a lot of water and transport is wasted. The tourism industry, in short, has become a new estractivism and is growing a lot.

.jpg)

In recent weeks we have been reading "proposals" for the recovery of the railway line Castec-Soria and the maintenance of the Tudela train station in its current location, or for the construction of a new high-speed station outside the urban area with the excuse of the supposed... [+]

The restoration of the natural characteristics of the beach of Waukee began three decades ago and continues without interruption in the staged restoration to counterclockwork.

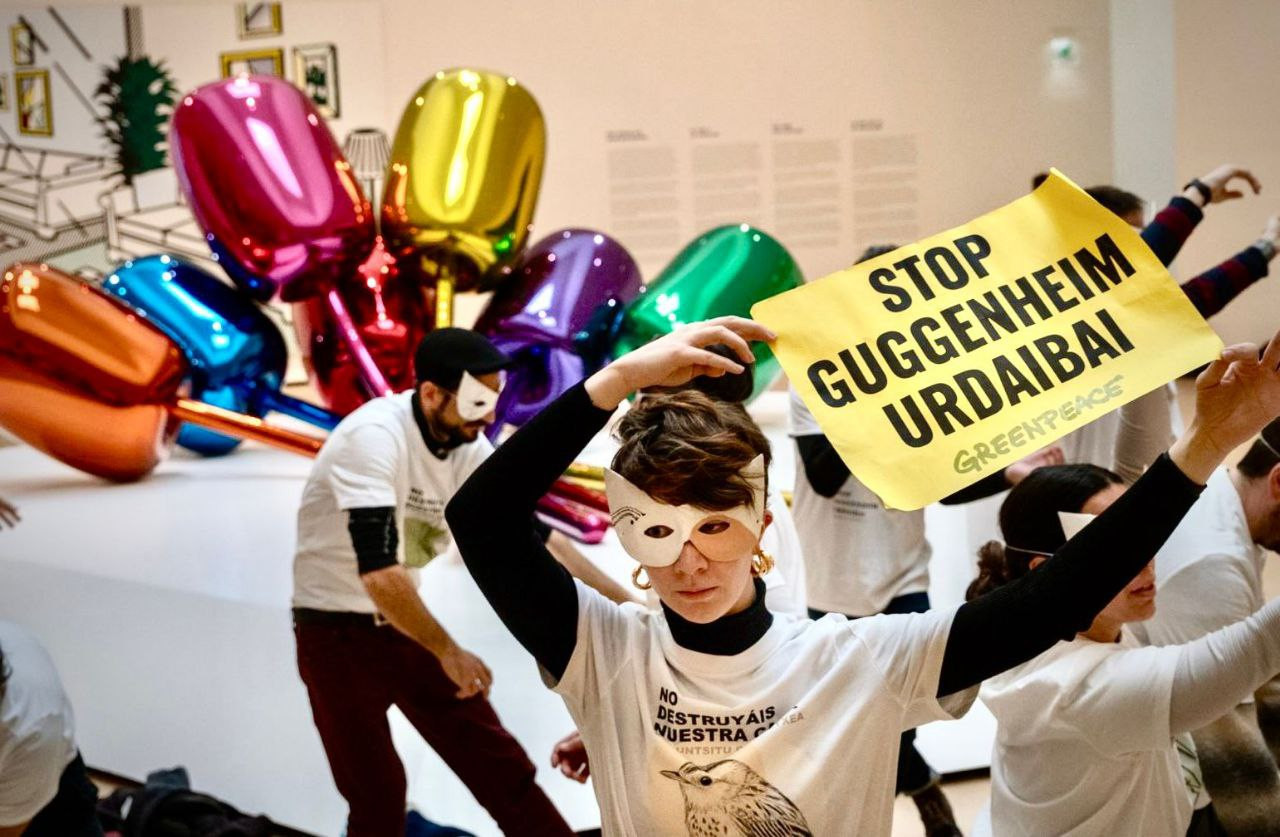

Samuel (Bizkaia) is an exceptional space, very significant from the natural and social point of view... [+]

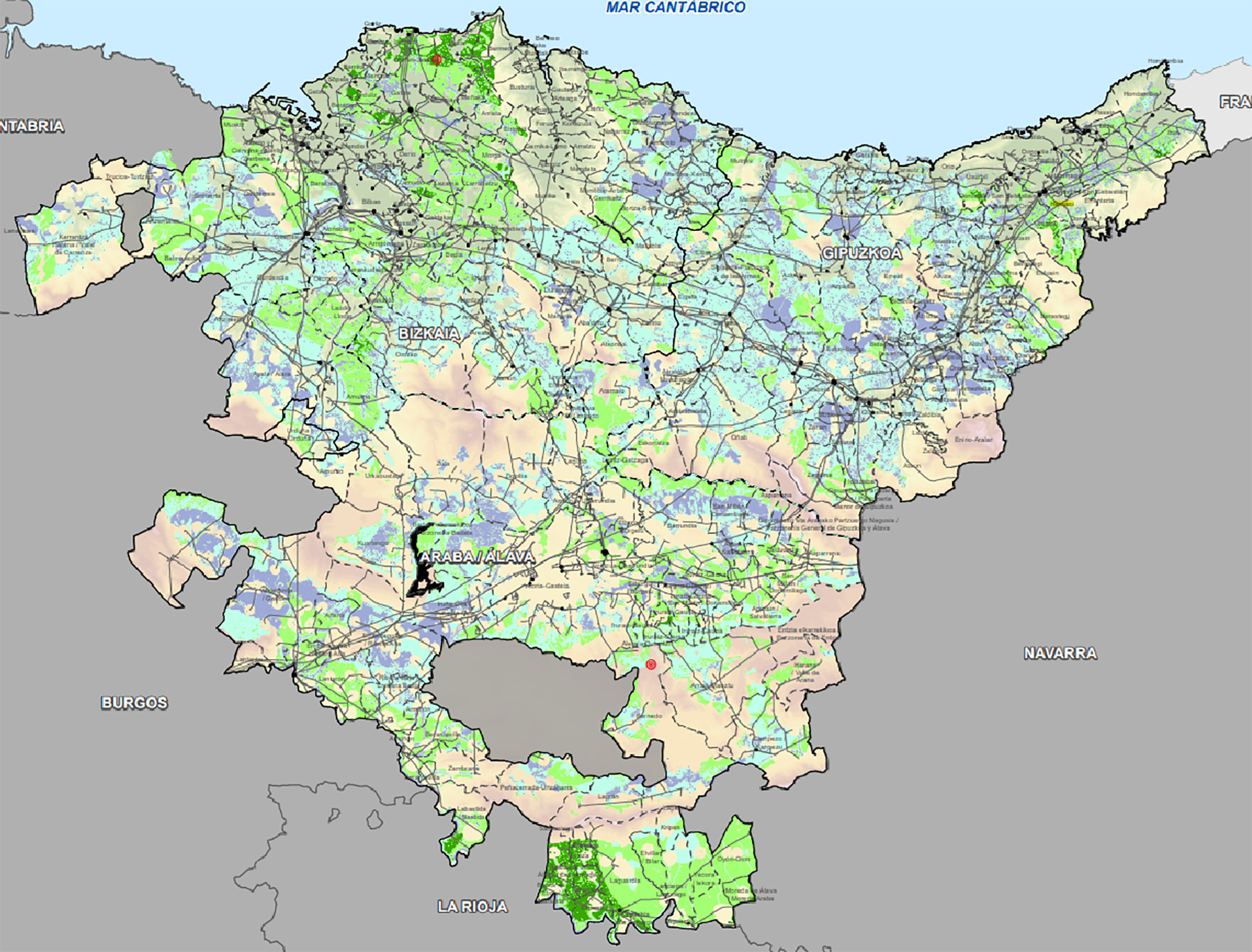

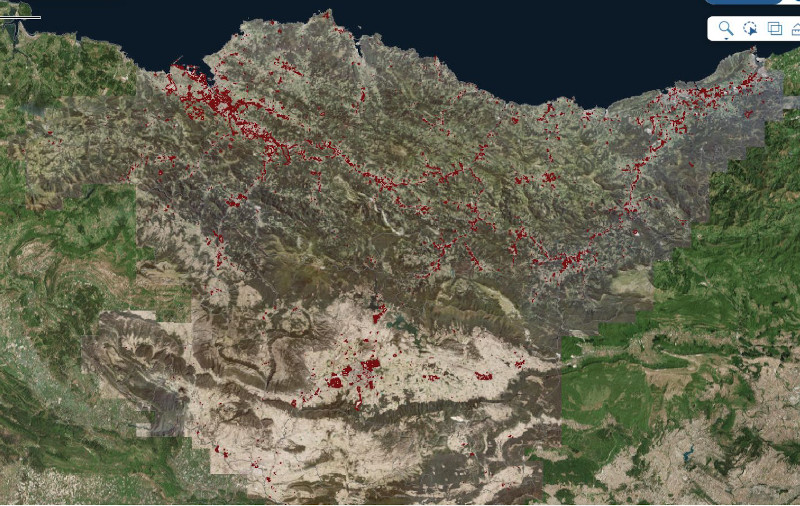

The update of the Navarra Energy Plan goes unnoticed. The Government of Navarre made this public and, at the end of the period for the submission of claims, no government official has explained to us what their proposals are to the citizens.

The reading of the documentation... [+]