Collective responsibility in the face of male assaults

- Outside the Aggressors used at parties! Is the motto enough when the aggressor is a member or friend of his own group? The Emagin Association has proposed its own protocol for the management of male aggressions within the group, centered on the transformation and repair of pain. The elaboration of this protocol serves not only to prevent attacks, but also to prevent attacks. In this sense, Emagine has published a guide and provided resources for each group to elaborate its protocol; the involvement of all its members is fundamental and the responsibility of men and women as key.

It is very interiorized that male violence is not tolerated at any party, and thanks to the work of the feminists the protocols to combat the aggressions are underway in most parties. The functioning of these protocols has been well known by Idoia Arraiza Zabalegi and Idoia Trenor Zulaika, militants of the Basque Country Herriko Bilgune Feminista. “How many times have we put the Aggressor out! banners. But when the attack is within the partnership, it's our lifelong partner or it's our friend, it's not that easy to do it. That is why we seek other forms or philosophies, and through experiences we have been maturing the protocol based on the principle of reconstructive justice,” they explain. In other words, along the same road as the protagonists of Larrune in May, they believe in a non-punitive and transformative model, opening a space for dialogue, they always find it legitimate any response to an attack, “but something else is the process that must be done as a partnership”.

Arraiza, a member of the Emagin Association and coordinator of the Trenor Bertsozale Association, has spent a lot of hours reflecting on the guidelines for the development of protocols for the management of machista attacks in the associations and collectives that Emagine has just published. It is clear that this guide is a proposal, a tool and that there is much to do: “It’s hard because we’re working with people’s lives and emotions, but what we’re doing is the most important thing.” Arraiza welcomes the growing interest of groups in male violence and encourages all associations to use the Midwife's Guideline for prevention. “Many already ask us for help when there has been an attack, when there is a need, but it is important to work before.”

As Trenor remembers, machismo always exists, as does racism and other oppression within patriarchy. “Even if you are convinced that this is not going to happen in your partnership, it is not the reality. You have to be prepared because they can and because they happen.” It says that it is important to have consensual group guidelines or have the terminology elaborated: “When there is a fire all have to follow some guidelines. Also in case of machistan aggressions”. And they stress that the responsibility of all to agree on these guidelines is “key” for two reasons. On the one hand, to avoid leaving the burden of the management of aggressions only to feminists and, on the other, to make these protocols more real and feasible, accepted by both men and women and therefore respected by all. Likewise, when the protocol is accepted by all members of the collective, they affirm that it will already be possible to achieve two main objectives: women will feel more protection and encourage men to walk “more carefully”.

Idoia Arraiza: “For our militant and emotional culture in Euskal Herria we are green in the management of internal conflicts”

The guide offers practical resources for the elaboration of the protocol in a participatory way, adapted to each group, which have been used by the Bertsozale Elkartea Association, advised by Emagin. Trener thanked the debate and reflection that led to the elaboration of the protocol within the group, as well as the opportunity all the participants had to work on male violence. However, it recognizes that it is “very difficult” to manage the contradictions that appear when passing theory to practice, and considers external understanding as necessary help. It also fears whether groups are not prepared to manage internal conflicts themselves: “Seeing the emotional and militant culture that we have come in Euskal Herria, which has been very rational and very hard, we believe that we are still very green, although progress has been made”. He pointed out that groups should invest more in contracting external advice.

Where do we start?

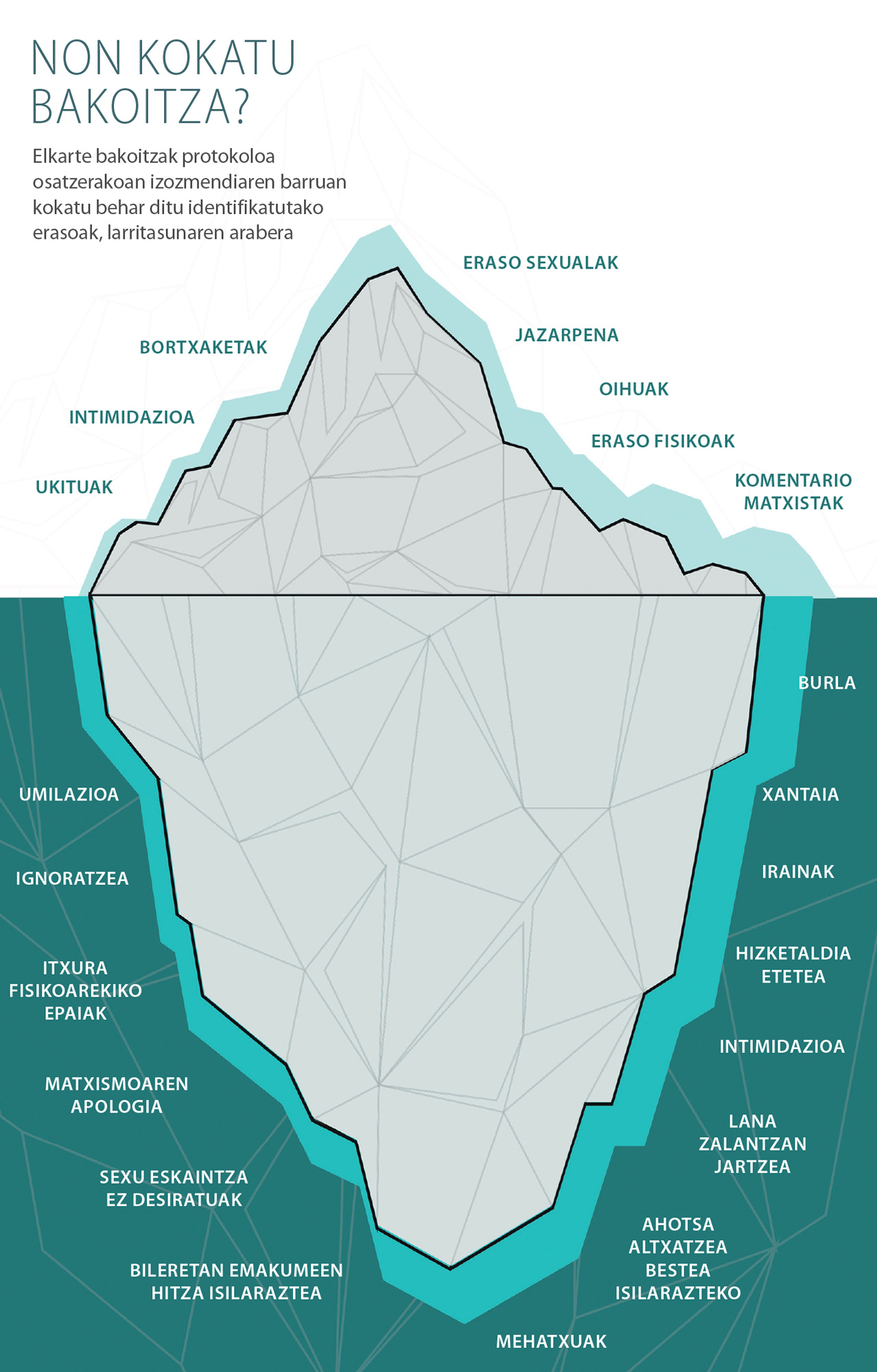

First of all, the Midwives' guide recalls that training is essential: feminist work, workshops on masculinity... The first step is feminist awareness and awareness, on which it will decide what is male aggression and how to act in each case. First, team work aggressions will be identified: “We will distribute post-it to the participants and each will write different attacks (attacks, situations of discrimination, underestimations, etc.). ),” explains the practical guide. Later, these post-it will stick to the drawing of an iceberg depending on the intensity of the attacks: from the most severe (above) to the least severe (below). They shall be classified into three, four or five groups, and the measures and procedures assigned to each group shall then be determined according to their severity.

Can it happen in this exercise that some man does not accept aggression as the case proposed by another? Well, according to Arraiz and Trenor, the opposite often happens: “Men are often the most radical or the most punished.” This attitude is not casual, but, according to Arraiz, “men have the need to express themselves very visibly and publicly as feminists”. Also, Trenor believes that men need to differentiate themselves from the aggressor and say they are “very opposed”. “Even if they are friends, they share their whole lives, perhaps they are accomplices of macho behaviors… they don’t want to identify with him, and sometimes they adopt this attitude unconsciously.”

Aggressor or aggressor

Unlike the previous midwives' guides, this time the terms of aggressor and assaulted or victim and aggressor have been chosen. Among other things, not to fall into the burden of labels. “Being an aggressor gives you an identity that seems to be the one you are for 24 hours from when you are born until you die. We do not defend it. You've made an attack, but it doesn't mean you have to do it all the time, the transformation capacity is higher." Trenor explains the victim label: “Women who have suffered aggression are sometimes very empowered and have no extra consequences, especially if we talk about the most serious assaults. But if we label the victim, we put the weight on them.”

Idoia Trenor: “Even if you are convinced that in your partnership there will be no machic attacks, it is not the reality”

They add another nuance: men more easily recognize that they are aggressors. However, Trenor sees that men find it hard to recognize the pain they have done. Because when those who have “minimal feminist awareness” look like aggressors, they wake up to a lot of “resistance”. “Because you have to exercise with yourself to recognize that you have caused pain.” So far, you've seen that's the hardest thing: accept it. In some cases, men recognize that women have been attacked, but not that they have been “assaulted.” The word aggression is therefore the one that generates resistance. Both assert that it may be more effective to use different terminology in lower intensity attacks, such as machist attitude. “They would probably more easily accept what was done.”

Avoiding social death

In the first line, both have seen the “aggressive attitude” of men towards other aggressors. “We have also seen real boycott, especially on the part of men, which does not help to meet the target.” That is, social death or exclusion will frustrate the transformative process; it is expected that whoever has attacked through reintegrating justice will return to the collective (if he has ever gone), after a process and after correcting the errors, to perform a “feminist reinsertion”. But if the perpetrator of the aggression is discriminated against, neither he nor the collective will be able to carry out any process. “What we want is for the whole collective to do a job and for the men to think about how they have helped this attack so far: how they have been accomplices, what each one has to do...” They recognize that many pains emerge and that sometimes other men realize that they have committed some kind of machist attack and decide to start working the problem through workshops or therapy, for example: “Sometimes they thank him, they consider him an opportunity, even if it is painful.” This process interpedes with all the men in the group and everyone must get involved in making it really work.

Steps of the reconstructive process

1 / Anticipated: prevention, need to socialize the protocol

2 / Protocol activation:

· Analyze the information that has come to us about aggression

· Two main criteria to

define the nature of aggression: classification of aggressions and contextual factors · Approaching

the aggressor · Talking to the aggressor

3 / Management steps and measures: agree an agreement with the aggressor and work with the community.

4 / Monitoring with all parties

5 / Closure and evaluation

What if someone believes that the aggressor has to be expelled from the collective and excluded from activities? “This idea is still on the table,” they say. That is, it will be decided in each case whether the person is willing to continue in the collective. In many cases this point tells us that it raises conflicts: let us suppose that you have done the process and that you are willing to return to the group, but that some member of the group does not agree to share space with it. “This is very common, so it’s so important that there’s a small team that manages cases and takes steps based on what they decide.”

In fact, this guide allows you to create a team that will be responsible for starting the process, monitoring and closing with the three parties: the aggressor, the aggressor and the community. Therefore, the debate usually coincides with the participants of this working group, as many people do not understand the decisions of this group “after long hours of work and debate”. Large collisions occur with the community and many personal relationships can go to the “picota”. Trener has stressed the need for this group to “have credibility and legitimacy”, which will be strategically selected people.

“On paper everything is very simple, but in reality it is much harder. It is very difficult for everyone to be satisfied with what has been done in one case.” According to Trenor it is “impossible” and it absorbs a lot of energy to be in the team: “Something will come from one place or another, and it is very difficult to support and not take it personally. That’s why it’s important to be in groups, because it’s very tired.” Among other things, they have been suspended because the aggressor has not respected the request. “As a feminist in these cases, the feeling is that you’re doing wrong.”

Idoia Arraiza: “What is the point of knowing what happened? What is the morb? Question your safety?”

Who should be informed of the attack?

From the beginning of the protocol it is clear that the protection and repair of the aggressor is a priority. Therefore, the team is responsible for listening and responding to their needs. For example, he will be asked if he wants the community to have that information and what action he wants to take. “But it doesn’t mean that it will meet all your needs or demands. You have to make a way, and many times there are mines and rage. You want to hurt,” Trenor understands. That's why she recognizes that it's often difficult to stay in feminist justice. That is, the team has to go beyond what the casings tell them and try to fulfill what they have put on paper. Concrete measures agreed upon by all in the elaboration of the protocol will be applied to the aggressor, although there is often a desire to adopt stricter (or more agile) measures, both the aggressor and the community.

An example of this is the spread of rumours. Based on the wishes of the aggressor, the working team will decide what is appropriate to count and what is not. And the community must take responsibility for not divulging information, even if it wants to exchange with its partner. “Rumor only affects the community; it cuts through the root,” blunt Trenor. Both are in favour of not communicating aggression, provided that the security and tranquillity of all are guaranteed. Arraiz asks what to know what happened: “What is this for you? What is the morb? Does your safety hurt?” They consider that for the proper development of the process, the management of this information should be only in the hands of the work team.

It's the turn of men

They have warned that throughout this process there is a “huge need” for feminist men. In other words, conscious men need to work with other men. “Women have become aware and we are increasingly empowered. Now it’s the turn of men, they have to become aware, reflect on their virility and do feminist work.” In addition, they stress the need for men to be involved in the work teams in charge of the management of aggressions, as the messages transmitted by men “have more legitimacy”. But are the men of the associations of the Basque Country willing to take that step? What about women? The guide proposed by Midwives opens a space for debate and reflection.

Prentsaurrekoa eskaini dute ostegun honetan Marc Aillet Baionako apezpikuak, elizbarrutiko hezkuntza katolikoko zuzendari Vincent Destaisek eta Betharramgo biktimen entzuteko egiturako partaideetarikoa den Laurent Bacho apaizak. Hitza hartzera zihoazela, momentua moztu die... [+]

Antifaxismoari buruz idatzi nahiko nuke, hori baita aurten mugimendu feministaren gaia. Alabaina, eskratxea egin diote Martxoaren 8ko bezperan euskal kazetari antifaxista eta profeminista bati.

Gizonak bere lehenengo liburua aurkeztu du Madrilen bi kazetari ospetsuk... [+]

11 adin txikikori sexu erasoak egiteagatik 85 urteko kartzela zigorra galdegin du Gipuzkoako fiskaltzak. Astelehenean hasi da epaiketa eta gutxienez martxoaren 21era arte luzatuko da.

Matxismoa normalizatzen ari da, eskuin muturreko alderdien nahiz sare sozialetako pertsonaien eskutik, ideia matxistak zabaltzen eta egonkortzen ari baitira gizarte osoan. Egoera larria da, eta are larriagoa izan daiteke, ideia zein jarrera matxistei eta erreakzionarioei ateak... [+]

Elizak 23 kasu ditu onarturik Nafarroa Garaian. Haiek "ekonomikoki, psikologikoki eta espiritualki laguntzeko" konpromisoa adierazi du Iruñeko artzapezpikuak.

15 urteko emakume bati egin dio eraso Izarra klubean jarduten zuen pilota entrenatzaile batek.

Lestelle-Betharramgo (Biarno) ikastetxe katolikoko indarkeria eta bortxaketa kasuen salaketek beste ikastetxe katoliko batzuen gainean jarri du fokua. Ipar Euskal Herriari dagokionez, Uztaritzeko San Frantses Xabier kolegioan pairaturiko indarkeria kasuak azaleratu dira... [+]

Bi neska komisarian, urduri, hiru urtetik gora luzatu den jazarpen egoera salatzen. Izendatzen. Tipo berbera agertzen zaielako nonahi. Presentzia arraro berbera neskek parte hartzen duten ekitaldi kulturaletako atarietan, bietako baten amaren etxepean, bestea korrika egitera... [+]

Martxoak 8a heltzear da beste urtebetez, eta nahiz eta zenbaitek erabiltzen duten urtean behin beren irudia morez margotzeko soilik, feministek kaleak aldarriz betetzeko baliatzen dute egun seinalatu hau. 2020an, duela bost urte, milaka emakumek elkarrekin oihukatu zuten euren... [+]

Neska adingabeari sexu abusuak era jarraituan egin zizkiola frogatutzat jo du Bizkaiko Lurralde Auzitegiak.

1989tik 2014ra, Frantzia mendebaldeko hainbat ospitaletan egindako erasoengatik epaituko dute. 74 urte ditu Joel Le Scouarnec zirujau ohiak, eta espetxean dago beste lau sexu eraso kasurengatik.

Lau mila karaktere ditut kontatu behar dudana kontatzeko. Esan behar ditut gauzak argi, zehatz, soil, eta ahalko banu polit, elegante, egoki. Baga, biga, higa. Milimetrikoki neurtu beharra dut, erregelaz markatu agitazioa non amaitzen den eta propaganda non hasi. Literarioki,... [+]