'Austerlitz', hidden currents of memory

- At Antwerp Central Station, Jacques Austerlitz, a man who cannot remember his past, is without a storyteller in this book. The talks between the two will continue for decades and cities to clarify the memory of fog. We talked to Idoia Santamaría, who translated W from the hand of Igela. G. One of the most famous works of the German Sebald, published just before his death. On June 4, Santamaría will talk about this translation at the Book Fair and Basque Records of Ziburu.

This book has almost 400 pages and only four paragraphs. How did you receive your return proposal?

At first I was very afraid. He knew Sebald and had read Austerlitz, translated into Spanish by Miguel Sáenza. I remember when I read, it struck me a lot, and I remembered very well that as I read, I thought. how Christ returned this!

You encouraged it.

Yes. I knew it was going to be a big challenge: I would go wrong, but also fine. The worst thing about having four paragraphs is that it's very difficult to go through, because the text doesn't help you visually, and keep the same tone.

When did he return?

In early 2020, I delivered it in December last year. In the last three months we have been reviewing. The model has done a lot of work, because there are pictures, and I wanted to check them a thousand times.

I was surprised at the subject of the photos.

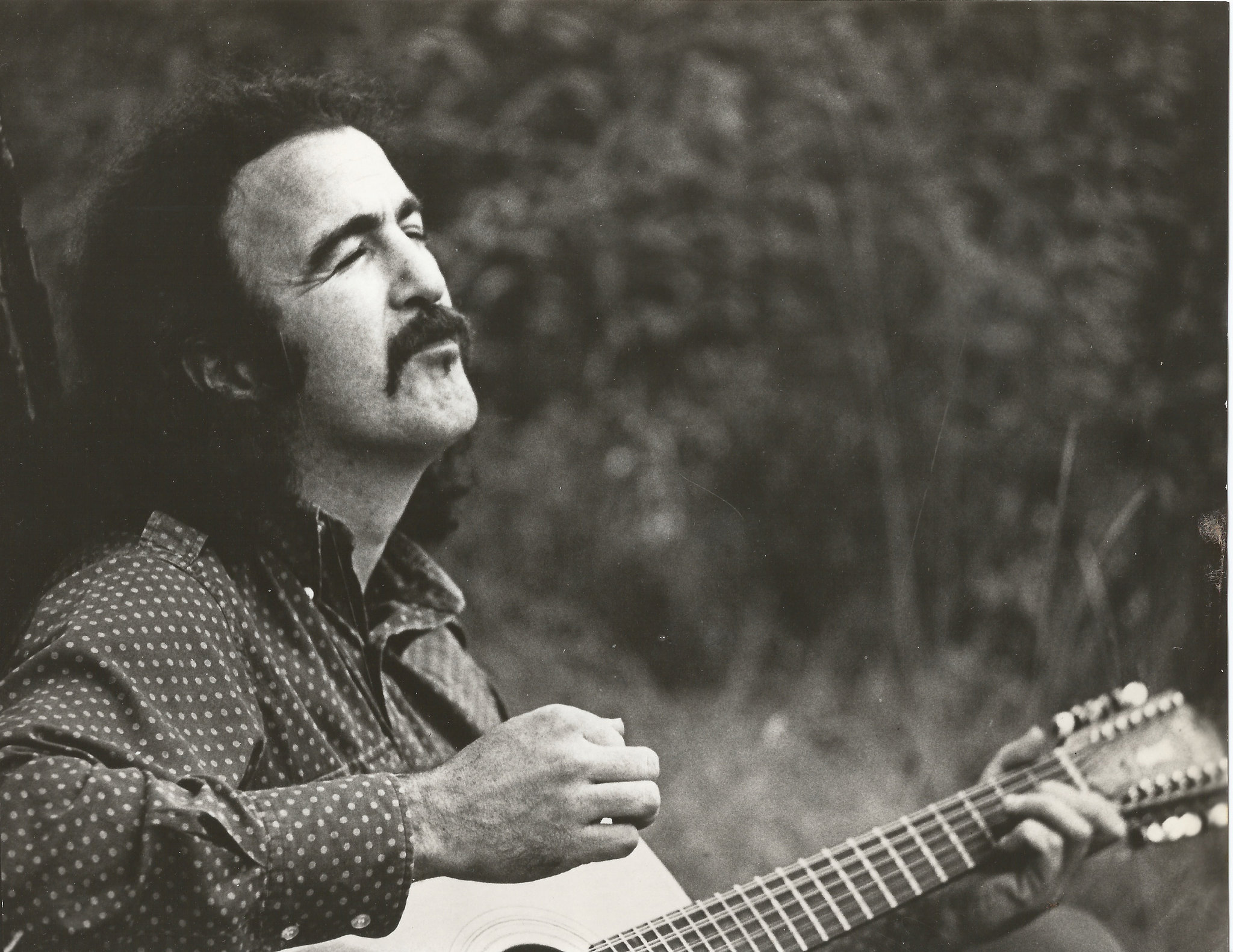

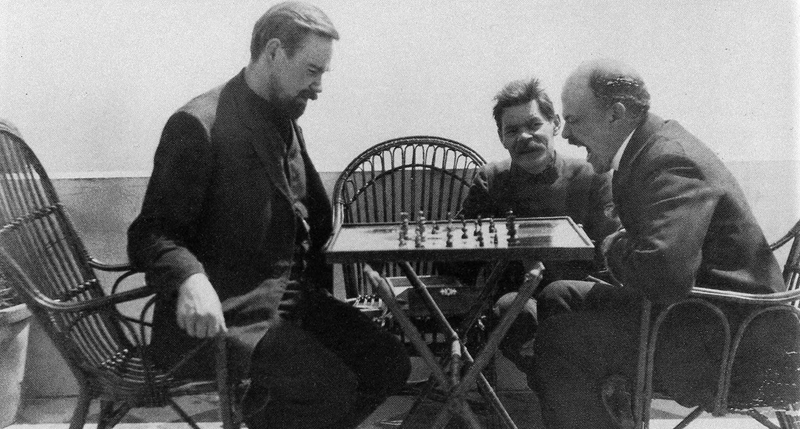

One of the debates about Sebald's fictional works is how they should be called: novels, stories... Sarrionandia, in the final speech, calls it the narrative artifact. The author himself, in conversations, used the name prose fiction, fictional prose, and uses photographs in all his works, not only in this one.

Some photographs are accurate, like the map of a building, but others show people and you have doubts about who they are.

Not known. We know that Sebalde did a great job of documentation and sometimes used photographs with permission of the files, although he also had controversy with it. He made a sort of mlange. Despite the intensive documentation work, this does not mean that you have exactly everything that belongs to that person. For example, Jacques Austerlitz said that it was made up of documentation of two and a half people. The photographs, sometimes made by himself, and many others he acquired in the furniture and other objects markets of ancient times. He liked this exploration a lot.

Reading for the first time Austerlitz made a big impression on him. Why?

What the writer explicitly writes – what appears in the book – is not all that counts, that admires me: all the time he suggests that there is something below what counts, a kind of slow current, and writing itself is the main generator of the atmosphere of history and a very important thread of history.

This thread is the Holocaust.

"Sebald cites the Holocaust explicitly for the first time in this book"

Yes, although he hardly mentions it in his fiction. It is mentioned for the first time explicitly in this book when the concentration camp of Theresienstadt appears. Moreover, it is very credible to tell how Austerlitz refuses to know that historical moment, because he knows that there is something very painful there. And I think Sebalde shows through writing how we remember things: there is no linear succession, it is not at all a chronological thing, but we do it jumping, a memory leads us to another, even if there is no obvious relationship between the two.

There are also many reflections on the history of architecture and the specifications of buildings.

In Sebald's books, colonialism always appears, directly or indirectly. Here, very specifically. The location of the book in Belgium allows it to refer to the whole African and Congolese question, among other things, how the riches from Africa allowed the creation of such monstrous buildings. The book begins with numerous pages on large buildings and building fortifications.

For me it's been very interesting, it shows you a lot about the history of architecture -- because Austerlitz, the main character of the book, is an architecture historian -- but it's given me tremendous pain. I have used an illustrated dictionary of architecture translated into the UPV by my colleague Alfonso Mujika, who has come very well.

Have you suffered any other head breaker?

Sebald has an infinite knowledge of many topics that you should consider when translating. For example, the book contains many descriptions of nature, like butterflies. There is talk of nocturnal butterflies, but with common name, not scientific. And what are the most common names? Normally, peoples and languages with a great naturalist tradition. I mean, England and Germany a lot. The Spaniards much less, and we zero. So I needed someone to tell me what common name I had to use in Basque for those names of the moths in the book.

How has the problem been solved?

I found the scientific name of some butterflies, very minority, and in an Excel table I put on one side the common name of German, and in case of the languages I have used for the consultation, Spanish, French, English and Catalan. Then, a biologist from Aranzadi contacted me with some butterflies experts here, some professors from the UPV, and the Association of Entomologists from Gipuzkoa. I said, "I'm going to put what you tell me, but tell me what to put in, that if one of you reads the book, don't think, when it comes to that part, what I've put in is barbaric."

You've finally given them.

When I was translating the book, I had just released a book of common names from the butterflies of Basque Country Day. But not at night, and I needed the names of the night! So, I used the names 8-10 that they gave me, yes. Lander [Majuelo, editor of Igelako] told me that with this translation at least the Basque country has won some butterfly names.

.jpg)

It's documented long before you do translations.

I really like that part, yes. While doing so, there is no responsibility or translation problems. You’re suddenly a volunteer student, and if you’re also working on a topic you like or an author… But it’s dangerous, because there may be as many times as you want and with an author like that, let’s not say. You can spend five years documenting and without translating any line and without charging a single penny. Perhaps it is a little fruit of my insecurity, it seems to me that if I do, when I begin to return I will take better. But some prefer to start from scratch. I think I have ever heard of Koro Navarro, who prefers to put himself in the skin of a simple reader and return from that figure without knowing it before.

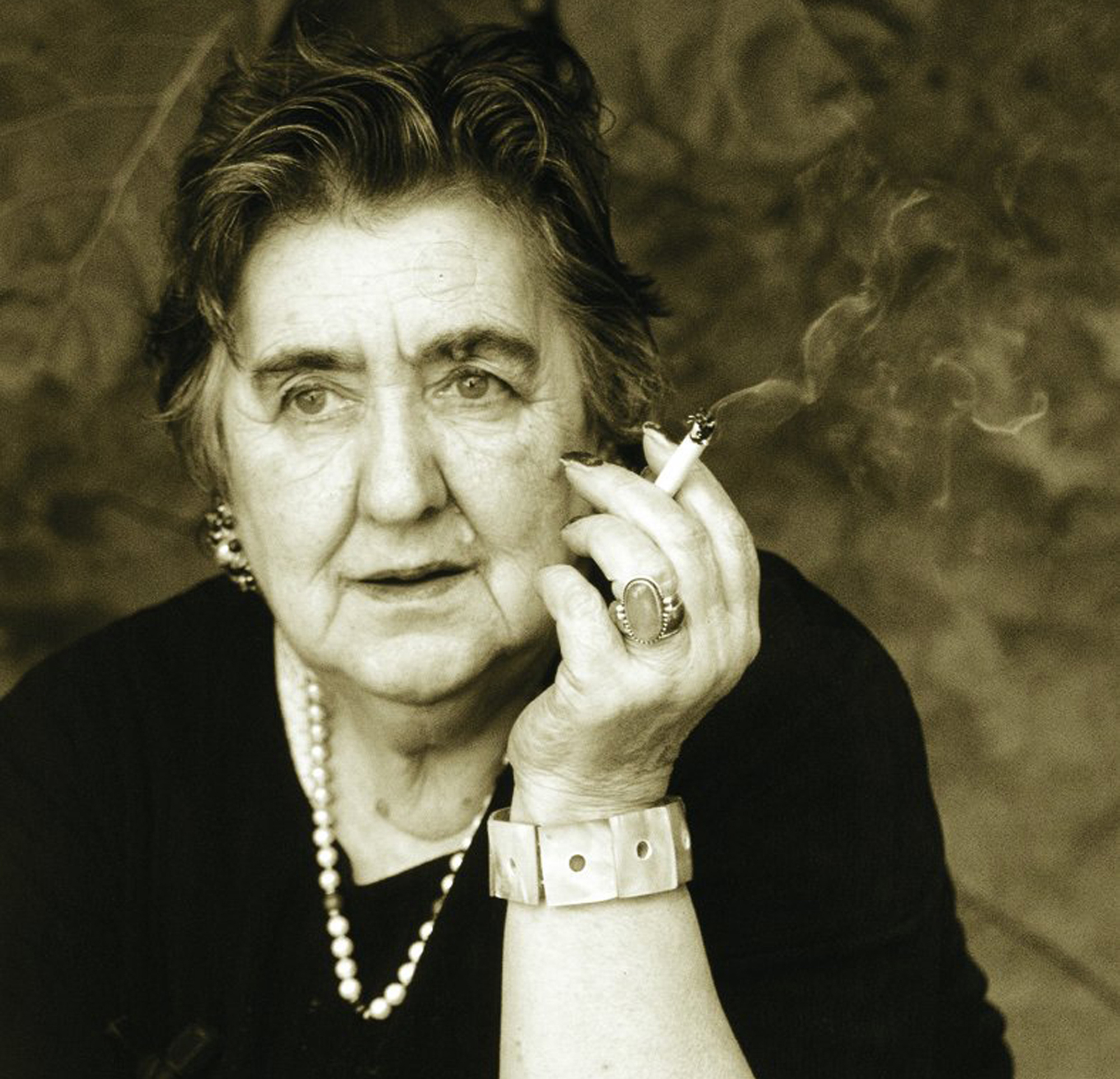

It has been translated by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Ingeborg Bachmann and W.G. in a fairly continuous series. Sebald. Before this, there were years that did not translate literature. Is there a decision there?

There are two decisions. On the one hand, go back to the literature. 1992 or [E.M.] I returned from English a work by Forster, at that time I lived in Bilbao, had a life quite dissipated, so to speak, and I couldn't do it: I did it occasionally, I left it, I started it again, I didn't settle for the translation. And on the other hand, for many years, I've had great home-care tasks, and I found it very difficult to do things other than everyday work. And since I wasn't happy with that initial translation, I stopped something like that, by the way.

When my father died, the first thing I decided was to go to Germany for a season to take some air, and to shake the German well, because I was a little rusty for not using it. And for two years, as I continued to work, I spent a few months of every year in Berlin, asking for a work permit, I pulled the C2 level out and said, yes, if I get any chance, I feel like it. One day, the first one, Dürrenmat, came out for competition, and they gave it to me. And as soon as I published it, the Bachmann competition came out, and I presented myself thinking they wouldn't give me, and so on.

And then Sebald.

Xabier Olarra told me that I was going to leave some responsibilities of the editorial Igela and that Lander was going to start. And he immediately proposed to me the return of Sebald, Austerlitz. And that's it. Things happen almost by chance and suddenly become a German specialist! The truth is that I am satisfied. I have been touched by three symbols of Central Europe, which I very much like, and they allow me to enter the history of that environment, which is one of my obsessions, which I am very interested in, especially its history and its artistic movement. I think we still have a lot to learn and there's a lot to come back from the literature there. A lot.

They gave him the Euskadi Prize for the translation of Bachmann. That you have it.

The truth is, it was a big surprise. I didn't expect it. I was convinced, and I am really doing so, that they would give it to Irene [Arrarats] [the same year that he published Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex]. Then a friend told me they don't reward attempts normally. The truth is that I do not know whether literary works and essays should have a category in the translation awards so that attempts are not always left out. Otherwise, if there was a single award for translation, attempts should be introduced more easily into this hype. In addition, the production of tests has increased considerably in recent years. And in the case of the second sex, something more canonical… Wouldn’t I complain, of course, eh? But I didn't really expect it.

Does that mean anything else?

I would encourage people to read Sebald, in Basque or in any other language, I do not say for my translation. He is a worthwhile author. I think now there's a trend that I don't like very much: it seems that if you recommend someone that's not very easy, you're a pedant, you have to be a cool, because it's super cool to recommend light things. And it gives me a little bit of anger. Are Henry James's novels easy? Or Virginia Woolfena? With this I do not mean at all that I am against the things that are read, heard or seen more easily, at all, but they have been works that have made me think and sometimes I have been discoloured by those who have stayed with me forever.

Disaster and exile go through Sebald's work, and yet his book ends and encourages him to start again. They have magnetism, they attract, and at the same time, as you pass the leaf, you get the feeling that something evaporates, it disappears. It is a very attractive combination, and in this sense, although one of the so-called ones is not easy, I think it is a highly recommended author.

Ekain honetan hamar urte bete ditu Pasazaite argitaletxeak. Nazioarteko literatura euskarara ekartzen espezializatu den proiektuak urteurren hori baliatu du ateak itxiko dituela iragartzeko.

Aste honetan aurkeztu da Joseph Brodskyk idatzitako Ur marka. Veneziari buruzko saiakera. Rikardo Arregi Diaz de Herediak itzuli eta Katakrak argitaletxeak publikatu du poeta errusiar atzerriratuari euskarara itzuli zaion lehen liburua.

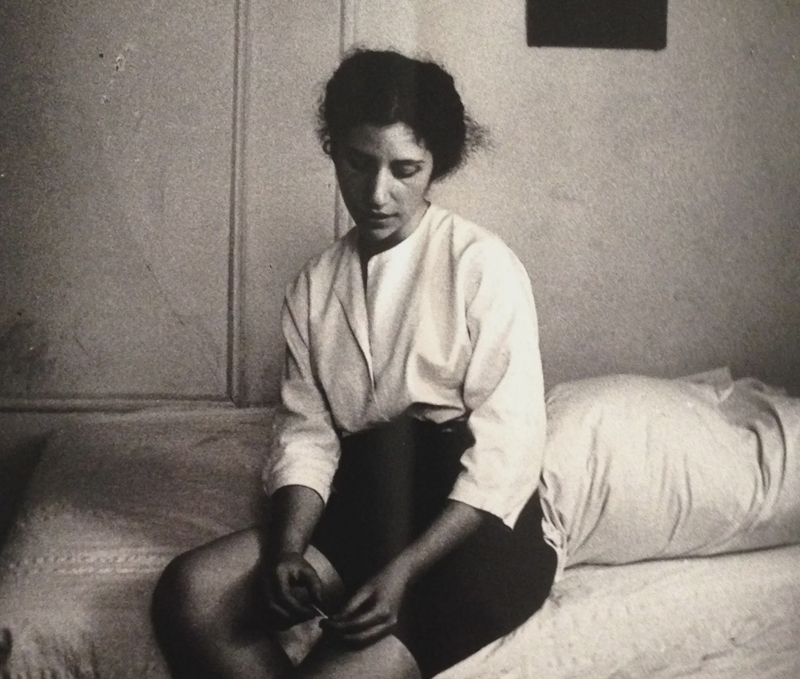

"There were women, there they were, I met them, but their families locked them in the mental hospital, put them in electroshock. In the 1950s, if you were a man, you could be a rebel, but if you were a woman, your family would lock you in. There were some cases, and I met them... [+]

Gauza garrantzitsua gertatu da astelehen honetan literatura euskaraz irakurtzea atsegin dutenentzat: W. G. Sebalden Austerlitz argitaratu du Igela argitaletxeak. Idoia Santamariak egindako itzulpenari esker, idazle alemaniarraren obrarik ezagunena nobedadeen artean aurkituko du... [+]

Asteazken honetan aurkeztuko dituzte Erein eta Igela argitaletxeek Literatura Unibertsala bildumako hiru lan berriak, tartean Maryse Condéren Bihotza negar eta irri (ene haurtzaroko istorio egiazkoak). Joxe Mari Berasategik euskaratua, idazle guadalupearraren obra... [+]

Wu Ming literatur kolektiboaren Proletkult (2018) “objektu narratibo” berriak sozialismoa eta zientzia fikzioa lotzen ditu, Sobiet Batasuneko zientzia fikzio klasikoaren aitzindari izan zen Izar gorria (1908) nobela eta haren egile Aleksandr Bogdanov boltxebikearen... [+]