"In my literature there is a constant struggle to dismantle the figure of the terrorist"

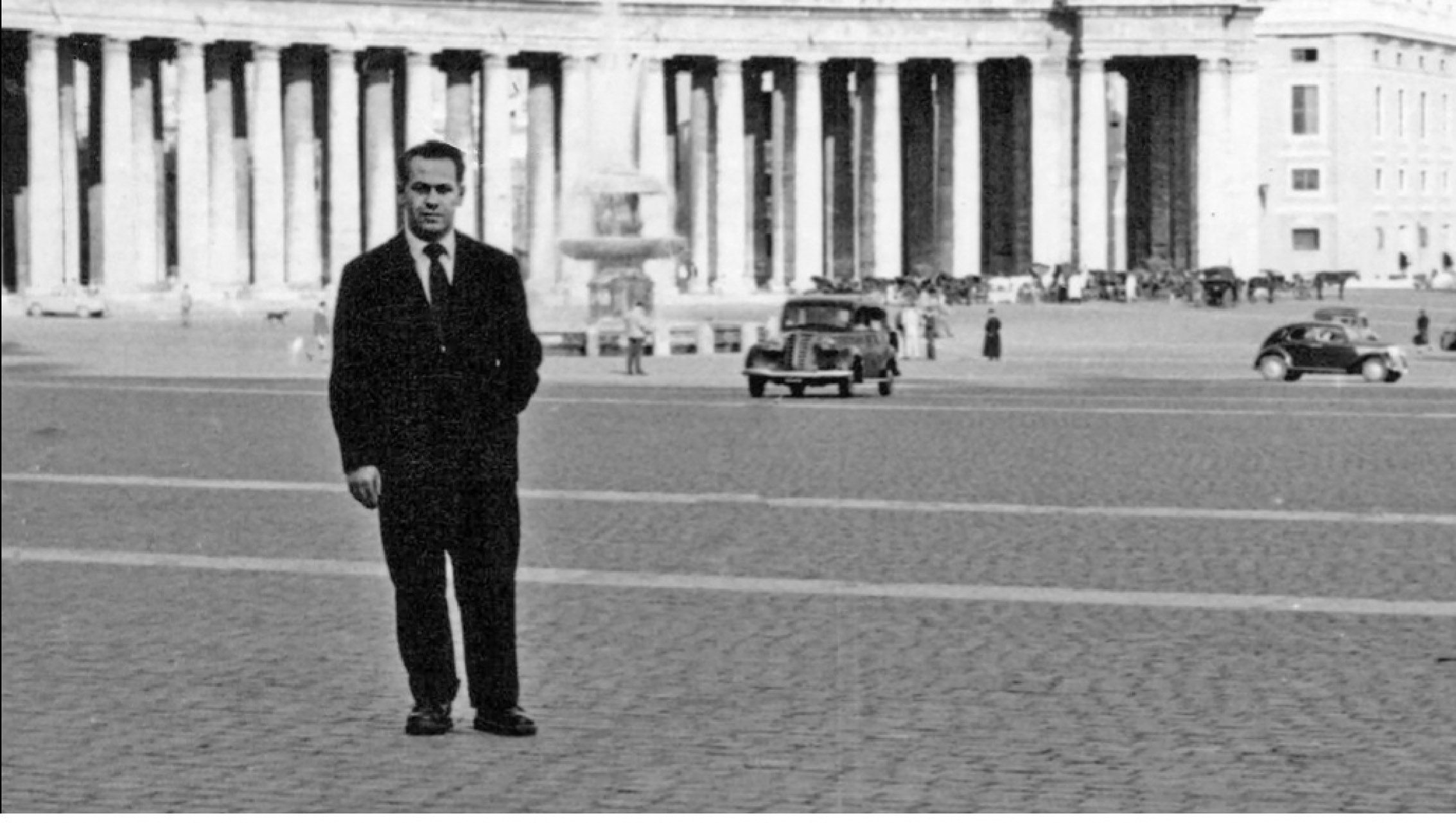

- We are in the Pontika district of Errenteria (or Orereta). At the bar Mikel we have a quote with Lander Garro to talk about the novel Faith that he published last year at the hand of the publisher Elkar. Although the environment is not well known, there is something familiar in this working-class neighborhood. Yes at least for those who read Garro’s first novel, because in these streets was the protagonist of the novel Contraria (Susa, 2010). As well as a writer, filmmaker and photographer, before starting the tape recorder has talked to ARGIA photographer Dani Blanco about how writers are portrayed in the press. He says that he is tired of possessing intellectuals, that he feels like a writer, that he is not the same thing. REC.

This desire to be a writer was one of the things that the protagonist of the novel The Adversary had in mind.

For me, it's the writer who liberates a guy in a fairly elementary way. In short, when do we learn to write? At six and seven years? The writing process is for me something related to neurosis and also that literature that interests me, a somewhat broken, psychological writing ... If I didn't write to me, I would be very worried, because I'm a very unbalanced person. I have to write, tell myself who I am, so I always write from an alter ego. There are no traps, I am more or less the one in that book, but there is always a beautification. That's the writer's trap to seduce it. And this doesn't have such a direct relationship with intellectuality. Alain Badu or Michel Foucault, for example, these kinds of writers who have the capacity of a Christ to sort out ideas, to perform scientific observation of the world... I don't know how to do it.

In fact, whoever reads Faith enters the protagonist's head. I found it a kind of synthesis between the Contraria and the Little War (Susa, 2014), I don't know if you agree.

Yes. On the contrary, he was very "writer", he had prose freedom, even of characters... In the book were people who didn't have a reduced intelligence and didn't have that drawback. In the small war, I had to manage a child's vision and had enormous limitations, because there is a fundamental rule in the literature: credibility. You can't get a kid thinking about things that are too smart. In Faith, I got a flight that deserved to be handed over to the Lesser War character.

Working with autobiographical material would make you remember the facts you have.

In essence, the facts present in the novel are always painful and traumatic, which then become the center of the novel. To do so, memory is fundamental. But then the synthesis exercise that a novel asks you for is so brutal, that in the end you have to do everything. And you give yourself to this exercise, no complexes, because being fiction can do whatever you want. I would say that my three novels have a lot of fiction, much more than memory.

In addition, memory is very diffuse, we think we remember everything, but it's not. For example, the judge's office. Imagine, there's a place you can remember. Or the entrance to the police station. But you don't remember anything. Nothing. There is a continuous formatting that prevents you from assimilating things that happen in life, erasing things from the past. Most are invented, unless you say: "I have to tell you about torture, and detention, and ..." -- those things that have done a lot of harm to you. And what you want to denounce, by the way.

.jpg)

It has drawn my attention to the fact that the novel deals with these issues, how in some moments you have gone to humor. Has it been a conscious exercise?

No, not very. When politics goes into its raw life, you have to manage something that you're really big and start guessing how to do it without knowing how to manage it. I've always had that tendency to fit a joke. There's a very interesting book to understand this question, Intxaurrondo, by Ion Arretxe. The shadow of the walnut [The Garage, 2015]: what you have when you are detained is, above all, fear. And one of the mechanisms you use to fight fear is to create relationship with the other. What is that relationship? Nice. It does not work better than a joke. So you enter that dialectic, it's a certain language that invents so the police don't hurt you. And I think the book has it exactly. It's the result of an uncut dilogue, a conversation between me and the police, which I don't know how it will end, which is always there.

The protagonist of the novel, your alter ego, has nothing to do with what they accuse him of. It is also the story of a "lateral harm" of the conflict.

When I was arrested for the first time, the Vuelta al País Vasco, passing through Erlaitz, began as soon as I left prison. I went to see the race and I found the guy who repaired my bike. And he said, "Oysters, you're here, you've been released." And then: "And how did you get into such a movement? ". And I: "No, no, I have nothing to do with that." And he said, "Yeah, I don't think so." He was my mechanic, he had a relationship with him, and he was convinced that they didn't tell me in the face. He didn't say wrong, he just didn't believe me. And then I realized how hard it is to eliminate a stigma. I believe that my literature has been a constant struggle: how to dismantle the figure of a terrorist thought and built in some Spanish barracks. How to show what's below. Because the terrorist is a lie, a military propaganda, an attempt to dehumanize people. And for me, the most interesting antidote is detail, singularity. Showing that each person is singular is how it is.

The environment of harassment has a great presence in the novel. It constantly crosses with everyday life.

That is what I lived in Barcelona, I think a bit of science fiction. It's a very interesting and important dramatic element for me. That's why, when it came to telling it, it was important to tell it thin, to try to get the reader to understand how something like this filters out in their daily lives, how an element that is there becomes, that can suddenly disappear and that allows them to make a relatively normal life, but then what remembers...

... and what does not let you live with a minimum balance.

"It seems that the only thing that falls into the grip of repression is suffering. But still, there are tricks to keep living."

That's it. It's a way of explaining how easy it is for the state or for power. How far is a little game for them? They start from behind, then they disappear, then they come back ... And you're defecated. As they've taken you once, you know you're extremely vulnerable. And your little things from your day to day become extremely important, you live everything like it was the last time.

It has also included some moments of liberation: Similar to the well-known career of Jean-Luc Godarden Bande à part (1964), for example by fleeing the police. It is a message that has suggested to me: "Harassment and control is there, but not everything is won." Did you want to broaden this idea?

Yes, sometimes you manage to master and experience terror. And the book is in its entirety, how the guy goes to Barcelona and as far as he can bring all the juice to life: he has a project, he'll do an exhibition, he wants to make a documentary... It somehow tries to make life prevail, and that's very important. It seems that the only thing that falls to people in the grip of repression is suffering. And it's interesting to show that all those people who are different in their way invent tricks to live, to love, to be loved... Within all this logic, culture is very important, going to the movies, to a concert, to read a book ... These things become fundamental.

It seemed to me that he has also made a generosity exercise with the police officers harassing the protagonist. Xabi imagines his personal side. Although they do what they do, it has represented them very humanely.

In the literature there is a very important premise for me: respect and love for the characters. Have minimal honesty with these characters and not fall into the awkward temptation to dehumanize. Being thin as a writer belongs to you. And deep. But not only with the characters you want, but with everyone in the book.

There's a fundamental book for me. Jonathan Littell in Les Bienveillantes [Gallimard, 2006]. Imagine what a writer of Jewish origin does: he enters the brain of a Nazis, not to speak well about the nation, but to look at the nation from multiple angles. And for me it's a tremendous literary exercise, but also a human one. I don't know if my book does an exercise to that extent; in addition, I think in my case there's something worse off about them, but there's some of that -- an example of "everybody is the person."

You said that you have been left out of the literary world. Given the impact of past faith and novels, do you think your position is changing?

I had a very misleading start in literature: when I wrote the first collection of stories, I asked for the Joseba Jaka scholarship and they gave it to me. On the jury were Joxe Azurmendi, Koldo Izagirre -- people who were for me, I don't know how to say it, like the gods. So I knew Koldo, and for me he was the guy who wrote the new incarceration of old Agirre [Elkar, 1999], or Where is Basques’ Harbour? [Susa, 1997] book of poems... And when they gave me the prize, there was an explanation, why they gave me. I read his comments and spent a few months reading. So I thought I would get into the world of literature. What happened? I published [I now have new questions; Txalaparta, 2004] and a terrible silence that spread around the book, hardly received comments in the press. In Deia he was criticized by Josu Lartategi and nothing apart. And I learned what my place really was. And from there, therefore... it is true that when I published the Minor War it sold me two editions, I have also sold two editions with Faith, and I think I have had a good relationship with readers, but the literary system has always left me out: prizes, celebrations, Literaktum, Gutun Zuria, Etxepare... I think all this has to do with politics.

Do you think your political position has influenced?

Yes, I think my political positions are very uncomfortable. And that also happens to Edorta Jimenez, or to Joxe Austin Arrieta -- there are writers who have stayed in the background of oblivion. I don't have a thesis about it, but we live in Euskal Herria, and here politics is always in the equation, you can't take away your political origin. Then there are people who hide very well and try to suggest that they have no political position.

Do you have anyone in your head?

No, I'm not talking about concrete people. I believe that in Euskal Herria everyone tries to conceal their political position. And appearing finely, without producing noises. There is a perception that the claws of power are long and you have to be careful. I think that perception is held by everyone. That terror. Nobody says so, so clearly, but I think it's there. "Ufa, if I tell you this or I'm here, I'll get the label and goodbye. So, I showed up with the lowest profile possible. For example, sign something for the prisoners, but from a humanist solidarity". We live in a place where the same party has been in power for many years, it is normal for that to happen.

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]