“Mine is not a nice painting, it is tragic”

- It will soon be 50 years since the Pamplona Meetings took the capital. Funded by the business family Huarte, the city served as a showcase for contemporary art from around the world in early summer 1972, for a week. But in addition to art, the festival was a reflection of the political tensions of the time. The painter Xabier Morras (Pamplona, 1943) lived with great prominence as part of the exhibition The contemporary Basque Art of Encounters. He experienced censorship on his skin, but also the illusion of being able to open a gap to art in the Pamplona in black and white.

Franco and contemporary art, which before do not seem very compatible.

In Pamplona, the art world was not very accessible, the possibilities were very limited. There were few exhibits of painters painting the Magdalena Bridge or the profile of the Cathedral. The painting was dignified and responded to a social demand of aesthetic pleasure. But those born in Franco had one eye on us and the other on the outside. We got to drip, we didn't know much about the paths of contemporary art.

In this context, what did the 1972 Meetings bring?

The encounters were invented mainly in two things. One, in Pamplona; in a larger city they would merge. And the other, that the Huarte family has commissioned the organization of Luis de Pablo and José Luis Alexanco, two artists and not two experts, or two art curators.

For a week, in the city there was a concentration of the arts that were performed at that time in the world. Western art was mixed with non-western art. A traditional music group from India and at the same time John Cage, making music more rupturing. This state-of-the-art fusion and traditional arts was very beautiful. The Meetings were opened with a ball game by hand in Labrit. People all over the world and Labrit stop. Imagine how many ball games we've seen. Then we saw something different: the sound was John Cage, the movements of the pelotaris the contemporary ballet. That was beautiful and it helped us rediscover our own.

How did the people of Pamplona live?

I think most people in Pamplona lived with a mixture of wonder, surprise and rejection. It affected the young people, who had already begun to travel, those who lived in May 1968 and those who were more open to the trends of the time.

For Basque art, in principle, there were no particular spaces foreseen.

.jpg)

I was running the culture hall of the Navarra Savings Bank. For notice, I, who was responsible for this space, a month earlier I learned about the organization of the Meetings. The meetings took place in the city and then came to the tribe: “Here will be someone who makes art,” they would say. And they told us it was going to be a Basque art exhibition.

They didn't like it much.

I put a christ with his mouth covered by a plastic and put him twice on each side [pointing to the figure representing a police officer]. Who was Christ? We, all. And the adjacent, who spied on us. But they asked me to withdraw the work, as was done with the painting of [White Dionysus]. He refused to withdraw them, and Arri and [Augustine] Ibarrola, in solidarity, covered theirs. But it was important to me that Topaketak thrived. And so I pulled out the work and put another one. Subsequently, ETA placed a bomb in a car and the PCE wrote a manifesto criticizing the Encounters with the intention of giving an image of normality of Spain.

How did you experience those criticisms?

Imagine that speaking as Medici of a millionaire family was forbidden to organize something that no one could organize in a country where it was forbidden by your power. That was what was criticised and they were partly right. But according to this we could do nothing. And it was about opening cracks to the system. It was easy for those intellectuals who came from Madrid. But what for those here? For us it was vital that Topaketak had continuity.

But they didn't go on. No other editions were organized.

That was our greatest misfortune. It would be very nice for Pamplona and for our people. But look at what city hall we had here, what a deputy. The power elites here probably didn't like it too much.

The meetings did not, but you followed your artistic trajectory. The 60-year work is not easily summarized, but how would it be described?

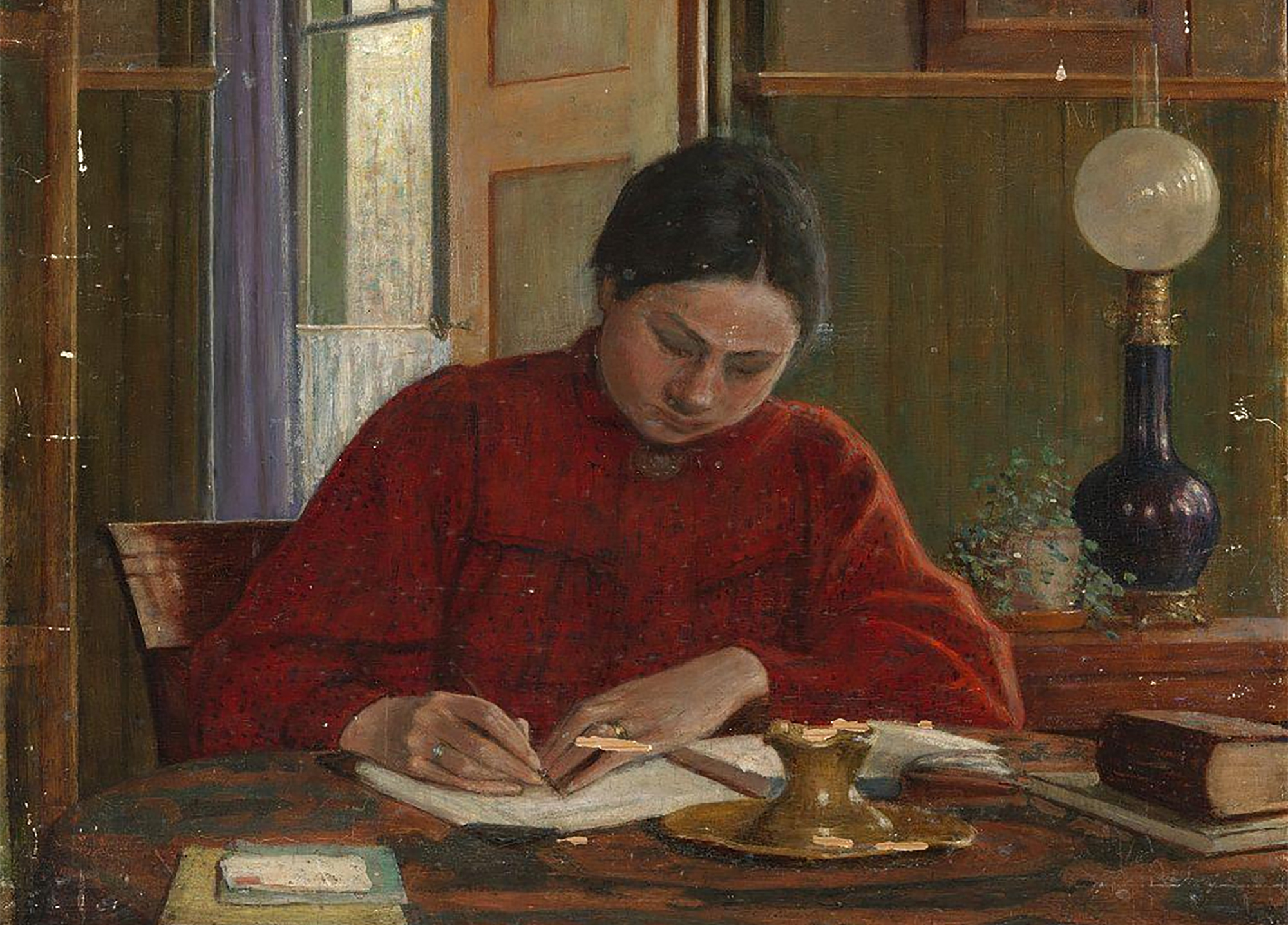

Mine is not a nice painting, it is tragic. And I've often wondered why. If I was born in the Netherlands I would have another touch. Here Franco was huge. When I was five years old, I listened to his people quietly about those who were shooting at the Castle of Pamplona. All of this affected me a lot and my painting has a dramatic and tragic fate. What do people want at home? Nice, nice, colorful painting. But I can live peacefully with the Goya Shooting. To me, more than tragic, I find it more authentic to what surrounds me.

The other day I heard you want to take off your backpack from the past.

But it's very difficult. And painting is therapeutic. I have been very traumatised by the shooting of Gaztelugibel. A few years ago, I made a picture of this. What appears there is a rigorous historical truth, it happened. I do not dare to prove it. It has been good to paint, but it has not healed me, but to put a bandage. The wound is there. And I dare not prove it. Therefore, there is freedom… beware, to a point.

The fascination with the image since childhood

“As a child, schools were terrifying, education was savage. But on Thursdays we had drawing lessons, and I waited really hard because for me it was a liberation. The colleague next door drew very well and said: “Well, if you see my brother’s drawings…” The next day he brought me a picture of my brother. It was as if a ray had crossed me, because suddenly I saw it clear that I would never do something like this. It was terrible frustration. But then they never devoted themselves to that, and I, the clumsy … Since then, I have always produced images. My complete biography is linked to the world of the image, I am fascinated by the image. Without that it would not be me, it would be another person.”

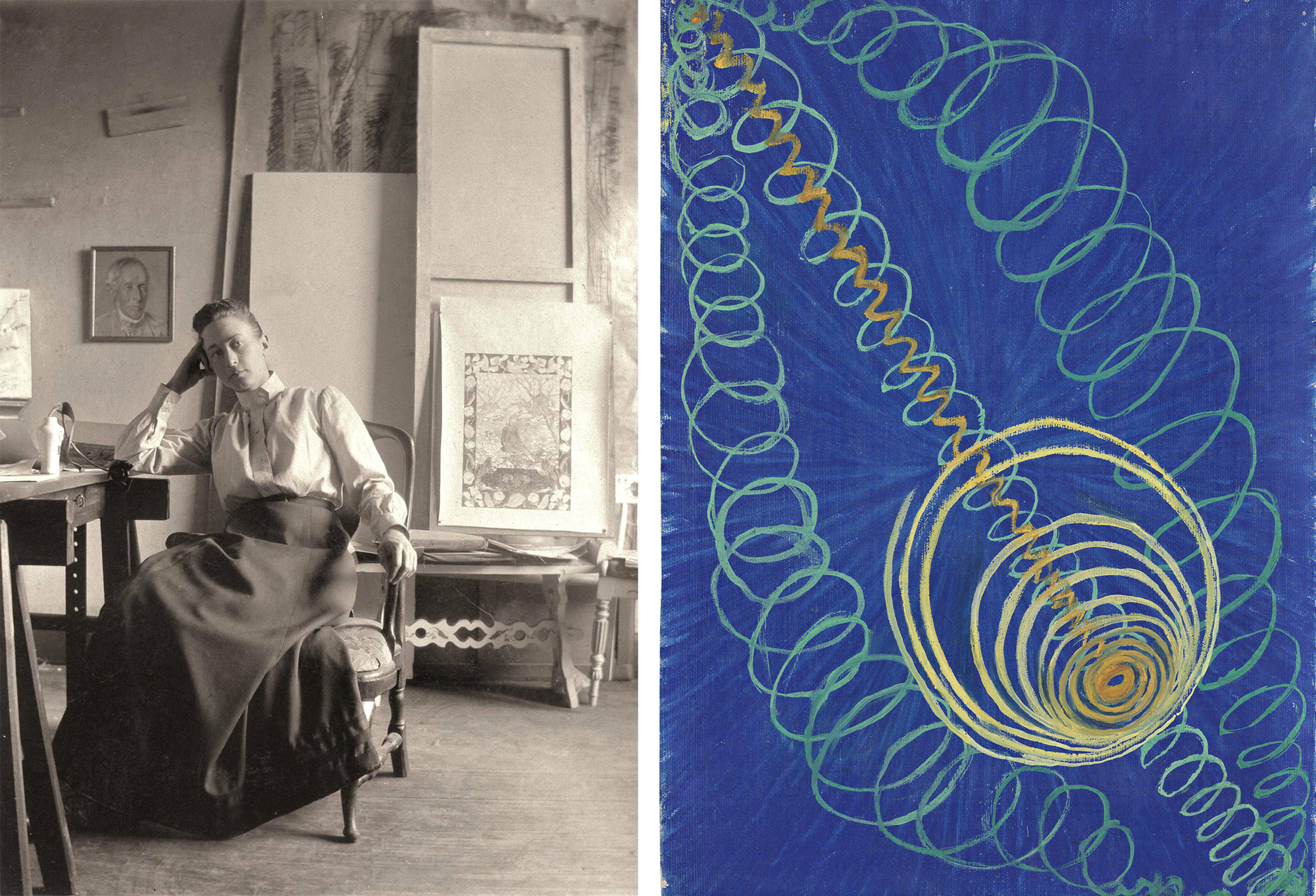

Bussum (Netherlands), 15 November 1891. Johanna Bonger (1862-1925) wrote in his journal: “For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on earth. It was a long and wonderful dream, the most beautiful one I could dream of. And then came this terrible suffering.” She wrote... [+]