The last whales are in luck: we may forgive life, because they collect more CO2 than the thousands of trees.

- Iceland has just announced that it will not hunt whales beyond 2024. Unlike the long-standing protests to denounce their massacre, the Icelanders now seem to give in for the money of tourists who come to see the live whales to the island. But in addition, the International Monetary Fund has realized that the retention of live whales can also be a business, as it is very good to fix CO2 by feeding its excrement to marine living things.

The International Whale Day, which is celebrated as a saddest and closest ephemeris on February 20, has come this year with good news for these mythic animals in danger of extinction: Iceland announces that by 2024, its fishermen’s ban on whaling will be extended forever. Despite the fact that the International Whaling Commission (IWC) banned its commercial hunting in 1986, Iceland, Norway and Japan have continued to practice this practice.

Among the whale genera, Iceland’s decision breathes especially into the skies (Balaeonoptera). There are 100,000 of them left in the seas. It was a whale that died landed at the Concha de San Sebastián in 2012. Since 2013 Iceland exported its meat mainly to Japan, but fishermen complained that this market did not. Only in Iceland does 1% of the population usually eat whale meat.

In recent years, however, a very different industry has been consolidated: tourism that allows us to see live whales at sea. It says it moves $2 billion globally, only $22 million in Iceland. Even Huarte reaches 300,000 people a year for this purpose. The success of the campaign by ecologists among tourists with the slogan Meet Us Don’t Eat Us – “Discover, don’t eat us” – is evident.

The Reykjavik government, which in 2024 is called upon to renegotiate the fishing quotas, sees this new market in the boat, and ran the risk of relaunching campaigns full of images of raw hunting at sea, wanting to approach Iceland chilling among foreigners. Why die, which brings us more living money? Heavens convinced that they have thanked the new gift that humans have given them by forgiving life.

But in addition to tourists, a new and more powerful lover appears in whales. The International Monetary Fund has just published in the quarterly newsletter Finance & Development an investigation with an exciting title: Nature’s Solution to Climate Change. A strategy to protect whales can limit greenhouse gases and global warming. The whale protection strategy can limit greenhouse gases and global warming.”) What scientists and ecologists have demonstrated a long time ago is that the powerful IMF appropriates something.

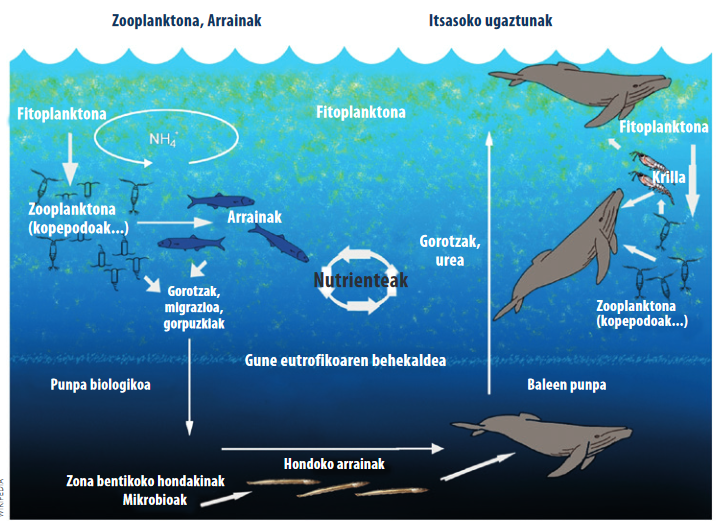

A whale traps 33 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere throughout its life and thousands of trees are needed to do so. The key to the great service lies in cacao, in the dejection that the whale hides in the sea. Although we've never seen it in documentaries, like any other animal, the whale cava -- and not a few -- scatters as many fertilizers as the largest animal on the planet.

PRICE VOUCHER

These high amounts of feces are rich in iron, phosphorus, nitrogen, etc. They feed marine phytoplankton. The microscopic bacteria and plants that give life to the oceans are responsible for 50% of the oxygen contained in the planet and for the annual sorption of 37,000 million tons of CO2, 40% of the total generated.

The famous krill feeds on phytoplankton, a tiny crustacean that serves as food for several ocean dwellers, including the whale (which will feed the phytoplankton again with feces…). And once it's dead, the whale will leave at the bottom of the sea all the CO2 accumulated in the body that weighs tens of tons.

That's why the whale is a time bomb for the ecological balance of the planet. Whale hunting was initiated in the 11th century by the Basques and for the next 700 years the seas of the European area saw this cetacean decrease. However, in the 19th century, industrialization also reached the oceans and by the end of the 20th, between 4 and 5 million whales were reduced worldwide to 1.3 million. Note the effect of loss on all living beings at sea, including krill, fish, mammals and birds.

“If whales – according to the IMF economists’ report – were allowed to proliferate up to the 4 or 5 million that existed before the start of industrial hunting, the number of phytoplankton would increase significantly in the oceans, which would attract a large amount of carbon. Only a 1% increase in the number of phytoplankton would capture billions of tons of CO2 more each year, as if suddenly two million more adult trees appeared.” Economists at the IMF have also measured the issue in money. On the one hand there is the money that they are mobilising with tourism today. But to this must be added the value of what these animals are doing on the carbon chain, on the prices of the CO2 emissions compensation market. All told, a big whale for IMF economists is worth $2 million, and among all the big whales, they easily outnumber a trillion dollars. Why not start rewarding whale survival?

“Aware that 17 per cent of the planet’s carbon emissions are caused by forest destruction, the United Nations has launched a compensation programme called REDD to reward those who support their forests, as they help keep CO2 out of the atmosphere. In the same way, we can create financial instruments to help regenerate the world’s whale populations.” This would finance not only the subsidies for final whaling hunters to stay on the ground, but also the route changes that companies will have to make so that large ships, other blind animal enemies, do not collide with whales.

We can also ask ourselves with the suspicious reader: Is a whale really worth two million dollars? Can living beings and natural resources such as water or wind be halted in cost-benefit calculations?

“Of course yes,” Doctors Greenwashing replied. And soon, if Petronor isn't Zabalgarbi or the Gipuzkoa GHK, they'll pay for their CO2 by protecting whales.

Eskola inguruko natur guneak aztertu dituzte Hernaniko Lehen Hezkuntzako bost ikastetxeetako ikasleek. Helburua, bikoitza: klima larrialdiari aurre egiteko eremu horiek identifikatu eta kontserbatzea batetik, eta hezkuntzarako erabiltzea, bestetik. Eskola bakoitzak natur eremu... [+]

Andeetako Altiplanoan, qocha deituriko aintzirak sortzen hasi dira inken antzinako teknikak erabilita, aldaketa klimatikoari eta sikateei aurre egiteko. Ura “erein eta uztatzea” esaten diote: ura lurrean infiltratzen da eta horrek bizia ekartzen dio inguruari. Peruko... [+]

Biologian doktorea, CESIC Zientzia Ikerketen Kontseilu Nagusiko ikerlaria eta Madrilgo Rey Juan Carlos unibertsitateko irakaslea, Fernando Valladares (Mar del Plata, 1965) klima aldaketa eta ingurumen gaietan Espainiako Estatuko ahots kritiko ezagunenetako bat da. Urteak... [+]

Nola azaldu 10-12 urteko ikasleei bioaniztasunaren galerak eta klima aldaketaren ondorioek duten larritasuna, “ez dago ezer egiterik” ideia alboratu eta planetaren alde elkarrekin zer egin dezakegun gogoetatzeko? Fernando Valladares biologoak hainbat gako eman dizkie... [+]