Brittle Wedding Toads in Verse

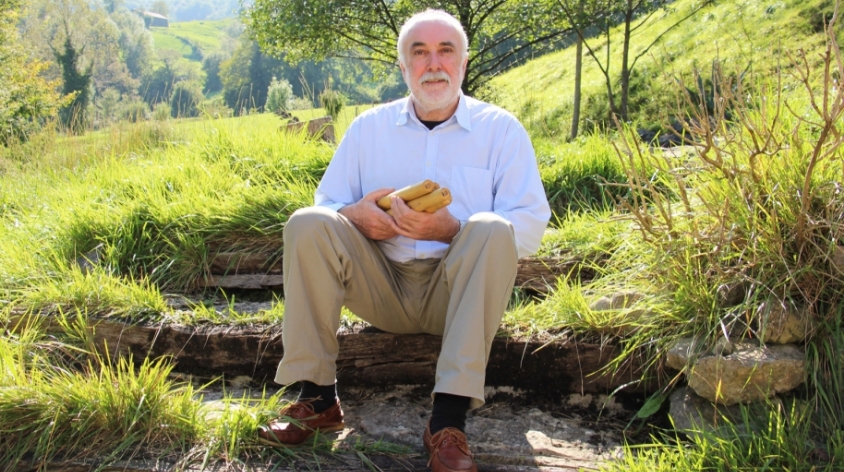

- The life of the verses lasted from the first third of the nineteenth century until the middle of the twentieth century. They were very varied, but a gender was often repeated: after marriage with the couple, but after being suspended for some of the changing reasons of the last moment, one of the counterparts often resorted to a bertsolari to extend the dirty rags of the other to the four winds. Antonio Zavala gathered these types of games in the book Lost Nupcias (Auspoa), which is 60 years old this year, and which he later picked up in a second book of the same title. Pello Esnal and Joxemari Iriondo inform us of this phenomenon.

There's a beautiful anecdote. Some cousins from Navarra were committed to getting married. At the last moment a wealthy widow showed interest in marrying her. The girl herself told the boy: “The other wants to marry me, but I’m not going to take that old man.” After a few weeks, the boy sat back. They both used something. I was going to the girl and she, crying, yeah, had to close the wedding with the old man. The boy, very angry, went to Pello Errota to put bertsos. The bertsos were disseminated and reached the old man. He also appeared in the stake of Pello Errota: “Did I deserve somewhere? As my girlfriend was missing, I had done nothing but “pretend”!” The miller explained to him that he only did his job. Estimates: “Then you put others in my favor!” But Pello Errota came to the boy just in case he asked him what he should do. He knew well what it was worth to put the verses – five hard ones – and he gave him so much in exchange for not putting them in. Once the bertsos placed were collected twice, the asteasuarra was satisfied.

A large part of the bertsos writings are part of the weddings detained on the road, some of which Antonio Zavala published 60 years ago in the book The Lost Wedding (Auspoa), a second collection was also made in 1999. It was quite common: if the marriage intention of a couple failed for some of the changing reasons of the last moment, the pretender resorted to a bertsolari to tell him wrong of the former couple. After giving shape to the purrustes, they would go through the printing press and open them to the four winds. In most cases, men were the ones who reported dirty rags against women, and even if it was against, most of the time it was on the initiative of the woman's father. It was therefore a matter of truth on request, but not always. Joxemari Iriondo says that on many occasions the bertsolaris themselves placed the former couples. “The last repertoire of verses of this style would surely be put by the recited Second Etxeberria. He told me: when his girlfriend left him 16 verses, but my mother forbade him to publish them somewhere and removed them.” In most verses, women are accused of not complying with the word, of not being faithful or being greedy – there are those who put their nun in and complain, that the bride has married her father, or that she is offended against the neighbours who had been at stake for the wedding to fail. Those relating to men are rather less frequent, and most are reactions from previous accusations that they themselves have made in order to defend their honour.

.jpg)

For Pello Esnal, one of the main features that makes the book a little difficult: “They are uncontextualized verses, and in addition, Zavala expressly removed the names and places of residence of the protagonists not to mention anyone. We perceived it very worried and there were no reasons for it. These verses used to have large sequelae, and it’s no wonder that we don’t want to renew that pain.” Iriondo believes that Zavala’s election was not just a matter of respect: “Erasing character and village names was a way to avoid complaints. Because in the verses followed the name of someone was mentioned and the family went to court.” Just in case he took special care in choosing the oldest verses –XIX. The first of the book dates back to the second half of the twentieth century. Thus, he assured that none of those cited in the verses lived.

But besides the lack of context and reference, there is something else: the Basque Country of the Bertsos is not the easiest thing to understand. “The older the verse, the harder the Basque is. Perhaps that retracts more than one, but it’s about getting used to it,” says Esnal. The bertsolaris didn't want their name to appear on the papers, so you can't tell who each lot belongs to. It is known that at least the leading bertsolaris performed these functions: Pello Errota charged five silver stills; Txirrita, which is later, charged ten. And because paid work gives the client legitimacy, sometimes they asked them to make arrangements: delete this line of bertsos, place it more harshly. Everything was to shorten the opponent's reputation, always without losing the credibility of oneself.

There were also “bertsos disabled”. If he moved in time to the slightest suspicion, at some point they managed to convince a former suitor not to give him vertigo. But most of the time it was useless. If they were published, the neighbors who were hungry for bait were swallowed up and opened at a stroke. The victim then had three options: to keep silent instead of exploiting the interior, to tell his point of view to another bertsolari, or to sue the pretender. They say that more than one man was severely punished.

.jpg)

You can't tell how many bertsos were posted on lost weddings, but if you look after Zavala, it's enough to complete over half a dozen books. The tradition needed a rooting for when Joxe Miguel Bitoria ‘Anbuerri’ of Asteasu saw a niche of business: he narrated in verse the ruptures between invented couples. Once the man sold a game to the woman, she made another one that responded to the man and, finally, one last one that goes back to the man to the woman. “A delivery novel, evidently complete,” says Zavala. Knowing that each lot was charging a big dog, you can imagine how much it was enriched. Notice, at death he left 13,000 pesetas.

One of the few media outlets of the time

The verses lost by the wedding are difficult to understand from the current view, according to Esnal: “It’s hard to believe how these kinds of verses were published and disseminated, throwing dirty rags between men and families. Sometimes, until some families leave forever.” Zavala clarifies something in the preamble of the book: something possible was at a time when popular life and literature were completely united. As the gap between life and literature widens, these practices gradually disappeared, as well as disturbances, sessions, hatreds and grudges. In short, it was a further variant of the broad phenomenon of verses.

It's also hard

to imagine the weight of bertso paperak in the society of the

time.

Care must be taken not to put in the same bag the old and new bertsos, as Esnal warned. Although they have the same name, it is new verses that were published in journals, and those that were published, or those that are sent to the journals today. On the contrary, the old verses are the initials, which were printed on loose paper in printing presses, for later sale. As has been said, they had a life of about 100 years, and according to Esnal, the Perretxikuak series by Luis Rezola ‘Tximela’, published in 1965, can be the last old bertso. But they were barely published after the last war.

It's also hard to imagine the weight that the verses had in the society of the time. Among those who put verses are Xenpelar, Bilintx, Pello Errota, Manuel Antonio Imaz, Udarrangi, Pedro Maria Otaño or Txirrita, sometimes on their own initiative, others on behalf of someone – as in the case of lost marriages. Once the lot of the printing press was extracted, the marketing phase of the verses began. Zavala describes the process: in fairs, markets, parties, romerías, the voice of bertsolari, who was “a man with a good throat”, could be heard anywhere. He would put himself in a street corner and start singing. He was approached by a lot of listeners curious about the new verses. What I could immediately buy was the verse paper, what I couldn't, or what I couldn't read despite the money, put my ears tightly, and didn't get away from the seller until I studied the entire memory department. Those who left home in donkey or trolley sang purchased verses, and by the time they arrived, almost everyone had learned them by heart. And there, too, there was always someone who was asking for berts.

The verses focused on religious issues – the lives of the saints, the missions of the people, the villancicos – social issues – the misfortunes of the boyfriends, the peripecia of the married, the life in the barracks, the social problems… – daily events – political news, war news, robberies, murders, neighbor unrest, lost weddings… – and also athletes – wagering harri-harri-betting. “They basically had the same function as the media today. They worked every color: pink, black or yellow,” says Esnal. The verses followed informed and created opinion; they allowed political and personal debates of all classes; and sometimes they exercised the counterweight function of the justice of the official institutions. Sometimes resorting to narration, sometimes to lyrical, sometimes approaching the press style, sometimes to the story. Esnal has recalled that the verses also strived in the “mental food that today’s media do so well” and that it is no coincidence that the greatest number of verses has been published in the Second Carlist War, from 1872 to 1876. To reach most Basques, and try to convince them, Bertsolaris was the fastest way for those on both sides. However, in the war of 1936 the opposite happened: by then the newspaper and radio were widespread, many people knew Spanish and the verses lost their old ideological function.

Aurten dira 60 urte Ezkontza galdutako bertsoak argitaratu zela –bertso zaharrak gaika antolatuta Auspoak atera zuen lehen liburua–. Esnalen ustean, horregatik da aproposa ulertzeko Zavalak zenbaterainoko lana egin zuen liburuz liburu, bertsoen testuinguruak banan-banan berreskuratzen eta berreraikitzen. “Karlisten bigarren gerrateko bertsoak liburuan dioenez, azterketa-lanak uste baino lan handiagoa eskatzen zion: hasteko, egilearen izenik gabeko bertsopaperak, ahal izanez gero, identifikatu; bakoitza bere testuinguruan kokatu; eta, ondoren, sailkatu”. Azken batean, bildutako bertsoek euren kabuz ez zuten argitzen noizkoak ziren, ez nongo borrokaldiak kontatzen zituzten, ez izendatutako pertsonak nor ziren. Bertso sorta mordoa zeukan aurrean, eta hori guztia sailkatzeko historia liburuetara jotzen zuen maiz. Horrela topatzen zuen liburu bakoitzaren hitzaurrea idazteko beharrezko materiala.

Plazaratu zituen pilatutako bertso haiek guztiak pixkanaka, baina ez hasieran aurreikusi bezala. 1956ko irailean –Euskaltzaindiaren gerraosteko lehen batzar irekian– jakinarazi zuenez, bertsopaperen bilduma handi bat plazaratzeko asmotan zen, estudio bat lagun zuela. Esnali iruditzen zaio liburu lodikoteren batzuk izango zituela buruan. Aipatu zuenez, 50.000 bat bertso zeuzkan ordurako bilduta, eta laster eskuratuko zituen beste sail eder batzuk. Jesuitek, ordea, ez zuten bilduma hura argitaratzea beren gain hartu nahi izan. “Kukuak oker jo zion”, azaldu du Esnalek, “nahiz eta gaur egundik zuzen jo ziola esan daitekeen. Ironiaz esanda, jesuitek arrazoi, behin behar eta: nola aterako zuten, ba, halako bilduma gordin, lehor eta irentsi-ezina? Bere gain hartu behar izan zuen lan guztia: bere argitalpena sortu, Arantxa arreba baliatu… Eta gure ikuspegitik garrantzizkoagoa dena: liburu solteetan banatu behar izan zituen bertsopaper guztiak”. Horrela plazaratu zituen 80 obra, horietatik 58 bertsolariak eta horien biografia ardatz hartuta –guztira, biografia handi eta txiki, ehun biografia inguru osatzeraino–. Gainerako 22 obrak, aldiz, gaika antolatu zituen.

Ehun urte horietan –XIX. mendearen lehen herenetik 1936ra arte–zenbat bertsopaper argitaratu ote ziren galdetuta, zalantza egin du Esnalek: “Bost mila? Hamar mila? Gehiago? Ez dakigu. Asko eta asko betiko galduak dira. Baina mordoxka bat badugu salbatua; asko, Antonio Zavalari esker”. “Azken batean”, jarraitu du, “Zavala bertsopaper zaharren munduak liluratu zuen, bertsoak eta bertsolaritzak bainoago. Auspoaren bidez –bertsopaper zaharren eskutik–, mutil koxkorretako oroitzapenak eta bizipenak abiapuntutzat hartu eta urtetan atzera jo zuen, harik eta ehun urte luzeetako historia, giroa, ingurua eta mundua berreraiki arte”. Hain aritu zen bilketa lanean suharki, teorizatzeko astirik ez zuela esaten baitzuen behin eta berriro. Baina denbora izanez gero, nondik nora joko ote zukeen Zavalak? “Bere idatzietan, antropologia aipatzen du tarteka. Berak, bestalde, historialaria izan nahi zuen hasieran, eta bere lanetan argi ikusten da historialariaren eskua”.

Egun, Donostiako Koldo Mitxelena Kulturunean 2.164 bertsopaper daude, eta horietako 1.638 dira Zavalaren funtsekoak. Artxiboetan begira ibiltzerik ez duenak hor dauka Auspoa literatur bilduma hirukoitza –Zavala hil zenean, 276 obraz osatua–: bertsopaper berriak sartu dira pixkanaka, eta gerora baita kontakizunak, eleberriak eta bestelakoak ere, baina guztiak ere bertsopaper zaharrak biltzen dituzten 80 obrek hauspotuta. Zein da ondare horren balioa? Esnalek garbi dauka: “Auspoa Euskal Herriaren –euskaraz bizi, euskaraz solas eta jolas, euskaraz kantatzen zuen herriaren– 100 urteko barne-historia da –intrahistoria, Unamunorentzat–. Edo, bestela esanda, Euskal Herriaren 100 urteko bizitzaren monumentu linguistiko-literario-historiko-antropologikoa”. Sarean dago edonoren eskura eta, besteren artean, ederki betetzen du hemeroteka funtzioa: toki paregabea da lardaskan aritzeko.

Vagina Shadow(iko)

Group: The Mud Flowers.

The actors: Araitz Katarain, Janire Arrizabalaga and Izaro Bilbao.

Directed by: by Iraitz Lizarraga.

When: February 2nd.

In which: In the Usurbil Fire Room.

In recent years, I have made little progress. I have said it many times, I know, but just in case. Today I attended a bertsos session. “I wish you a lot.” Yes, that is why I have warned that I leave little, I assume that you are attending many cultural events, and that you... [+]