Routes opened by Francoist victims

- Altsasu / Alsasua, Ribaforada, Castejón, Salvatierra / Agurain, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Sukarrieta, Bermeo... are currently stations of the Basque railway network. Trains arrive frequently and offer service. What we cannot forget is that these infrastructures were built by forced workers during the 1936 War and the Franco regime: prisoners, prisoners, slaves.

The use of slave labor was common in Franco. The workers’ battalions were formed by the prisoners of war first detected on the front, under the motto “to rebuild what they destroyed”. Later, on the verge of the civil conflict, they were part of the prison network of Franco “Nueva España”, called “Patronato para la Redención de Pena por el Trabajo” (Board for the Liberation of Labor Penalties). The prisoner had the possibility of shortening the sentence, since for each working day he was cut off from two sentences. Behind the patronage there were ideological and economic reasons: on the one hand, this system served to alleviate the huge number of post-war prisoners – as well as humiliating and humiliating the enemy – and, on the other, the state saved a lot of money and the contractors obtained great economic benefits. This Franco patron was legally maintained until 1995.

Although private work was sometimes carried out, it was customary to use prisoners to carry out large public infrastructures such as roads, dams, airports and even railways. The forced work that has taken place in the latter has not been sufficiently researched so far because of the difficulties of access to documentation, or rather, because of the obstacles that the institutions have placed, and by governments of all kinds and color that have not so far promoted or supported comprehensive research projects. In recent years this lack of interest has been addressed and in 2021 the Spanish public railway operator RENFE has posted information on the web about the repression suffered by railway workers, the database of the names of slave operators and the documentary The Sons of Iron (Sons of Iron) on the subject.

.jpg)

Railway workers in the spotlight of Franco

For Franco, many of the professions were especially suspicious. The brutal repression of teachers, or of gatekeepers, is well known, and railway workers were also classified in this category of suspects. 88% of the workers operating on the railway companies during the Second Republic suffered further repression. The slightest sanctions could consist of fines, layoffs or layoffs, but beyond that time, arrests, torture, imprisonment, death sentences... there were. An example of this repression is the case of Gumiel de Izán. In 2011, a grave covering 59 remains was excavated in the village of Burgos. They were all workers on the railways that were shot in 1936.

Forced labour served to alleviate the huge number of post-war prisoners, and the state saved a lot of money.

In the 19th century, the first railway line was built in the Spanish State, and slaves were also used. In most books it appears as the first line between Barcelona and Mataró of Catalonia, inaugurated in 1848, but the truth is that in 1837 the first railway line of the State was inaugurated, between Havana and Bejucal, when Cuba still depended on the Spanish crown. In that colony there was legal slavery until 1886 and, according to the law of capitalist economy, a well-known habit of using slave labor in railway works began. The train, of course, was not for public use, but to export the cane sugar out of the island.

In the case of the works of the twentieth century, on the contrary, the participation of the prisoners in the construction of the railways has been in the dark for decades. In recent years, Fernando Mendiola and Juan Carlos García-Funes of the Public University of Navarra have researched these forced works and published in a doctoral thesis and in various publications the results of their research on the railways.

.jpg)

(Photo: Aranzadi / Oscar Rodríguez)

Deputy Basque prisoners who died in Andalusia

The reconstruction of the destroyed railway lines was one of the main tasks during the war and the first years of the dictatorship: repair or reconstruction of bridges, reinforcement of tunnels, placement of lanes, certification of slopes... The new regime should recover these fundamental infrastructures for economic and strategic military reasons. Nearly 9,000 prisoners participated in this task, most of whom were detected in the war.

The railway networks of Euskal Herria did not suffer great damage during the 1936 War, so in our environment researchers have not found many references to this type of reconstruction work, but we do know of a disaster related to Basque prisoners. From August 1938 to August 1940, the railways were repaired in various localities of Extremadura and Andalusia, among which the reconstruction of the Alanis de la Sierra train station in Seville and the creation of a safety line were highlighted. But why was that station deteriorated? as a result of an accident on 19 November 1937. On that day, a speed train left the lane and 72 people were killed on the wagons: 57 were Basque Republican prisoners taken to Andalusia for forced labour.

.jpg)

The reason for this accident has not yet been clarified and no mortal remains have been found of victims supposedly buried in the tomb of Alanis de la Sierra, despite the efforts of the scientific society Aranzadi. In 2009, filmmaker Sabin Egilior recalled this story in the documentary The Long Journey, in which his family honored the deceased on that train.

Unfolding of railways in the Ribera and Llanada Alavesa

Once the majority of what was destroyed had been repaired, especially since 1940, companies and slave workers were entrusted with the construction of a second road along with several already functioning railways. These railways were developed in order to speed up high-intensity traffic journeys, facilitating the passage of trains. They used political prisoners who were far from their house in prison. Shortly thereafter, these prisoners were joined by another large group of young people born between 1915 and 1920.

The Franco board, which managed the forced railway works, continued to

be legal until 1995.

These generations were responsible for military service in the Second Republic, but the Franco authorities did not take this military service into account and forced them to replenish the service in its entirety. Many of them, with the disaffection label (anti-regimen), became part of the workers’ battalions. In our environment, there were two slaves who doubled the roads: Those who carried out the itineraries Castec-Cortes Zuera and Altsasu-Agurain-Vitoria.

In the southern line of Navarre, the section between Castejón and Cortes was doubled, occupying between 1,500 and 3,600 workers, depending on the time. The works lasted two years, from 1938 to 1940, and two workers were battalions: 13th and 149. These were works that required great mobility, which has made it difficult to carry out research, due to the scarce documentary footprints. The presence of personnel is documented in various localities of the area, such as Castejón, Ribaforada and Cortes, but it has not been easy for researchers to find later data. Apparently, the headquarters of officers and authorities was in Castejón, and the workers were moving the place of sleep when they were asked for work.

The unfolding works of the Altsasu/Alsasua line to Vitoria began in 1938 and gave rise to battalions 149 and 151, with a staff of about 1,150 workers – 1943 and 1944 to the 95 Punished Soldiers. It seems that there was also a battalion. The works in this area were not limited to the railway, but forced several workers to take the stone out and prepare it in the quarry of the Altsasu / Alsasua Solar to use it in the railway works.

During the identification work of the workers who were performing the section between Sakana and Salvatierra, the researchers received an unexpected help from the municipal archive of Altsasu/Alsasua, in which Mendiola and García-Funes obtained the results of the measurements and medical examinations carried out by the then municipal physician. Thanks to this they have managed to get to know the 83 participants of Battalion 151, and once again the surprise: among them is the only Basque, Joaquín Rebollón Cirion, born in Artzentales (Bizkaia) in 1919.

Between Sukarrieta and Bermeo, fleeing from prisoners

Rail slave prisoners also opened new lines that previously did not exist or extended existing ones. First, we had to prepare the ground, widen the trenches, drill the mountains to build tunnels, build bridges to cross rivers, prepare stations and platforms… In Euskal Herria we have examples of these works: Extension of the line from Amorebieta to Sukarrieta, by Mundaka, with the aim of reaching Bermeo. Compared to the previous cases, this work was carried out very late, between 1953 and 1956, and the company Banus Hermanos outsourced the prisoners. The participation of at least 60 prisoners is documented in the construction of the narrow railway section, but there are no required workers identified.

According to historian Juanjo Olaizola’s publication Forced Labour and Railways, the prisoners’ initial mission was to open a 500-meter journey, but with three intermediate tunnels, 310 underground metres. Later, the prisoners also worked in other jobs, setting rails or planning land to locate warehouses and stations.

Between 1,500 and 3,600 railway workers split between Castejón and Cortes, according to the time

In addition to the railway works, some prisoners extended the pier of Bermeo port for 20 metres. All these prisoners, while working in the Urdaibai area, also leaked, and in 1953 at least two people managed to make themselves known, as Olaizola found in various documents of the Spanish Ministry of Justice.

The dictator Franco himself opened the railway section between Sukarrieta and Bermeo in August 1956, although it was not completed according to some sources. Without any task, the workers’ battalion of the prisoners was divided into two groups: one of them was sent to the Mirasierra detachment of Madrid and the other to the Union of Murcia to do more work.

Issac Arenal, a slave in the public works of Alsasua

As a result of the lack of documentation or the obstacles to its consultation, prisoners' testimonies are often used. Among the captives who worked as slaves in the railway infrastructure we can highlight the autobiography of Isaac Arenal. Arenal worked in many villages, including Altsasu/Alsasua, and 95 Workers Soldiers Battalion (95 Soldiers). In the book Batailoia) he narrates his experiences naturally. In the publication that we can easily find on the net, reference is made to the hard day, the long walks with heavy material on the back, the wet cold that penetrated to the bottom, the hunger that could not satisfy poor or bad food, the occupational accidents suffered by colleagues, lice, lack of hygiene, harsh discipline, punishments, beatings, humiliations. The days were held from Monday to Saturday, from 8:00 in the morning until 18:00 or 19:00, depending on the natural light offered by the station. Mass was celebrated on Sundays and sometimes lectures were given for moral formation. Prisoners who received family visits on public holidays were an exception.

.jpg)

Given the shortage and scarcity of machinery to work, this shortage was compounded by the enormous physical effort of the captives. The company offered them uniform, mandatory clothing to facilitate the identification of inmates. Due to their great mobility, they used temporary sleeping bays, places that did not meet the minimum, cold conditions in winter and excessively hot in summer. Although they lived in these inhospitable conditions, some workers continued to work voluntarily, in return for a little salary, but under the same conditions as others, because, despite having served the prison sentence, they still had the exile sentence in force.

Over the years, the forced labour of the railways was declining until their disappearance in 1957. It's been several decades, but what these thousands of enslaved prisoners have built is still available. Thanks to these infrastructures, some were enriched, we moved and many others lost their lives.

.jpg)

Nondik abiatu zen proiektu hau?

Edurne Beamountekin batera Piriniotako Langile Batailoien ikerketa burutu genuen. Arlo ekonomikoan sakontzen jarraituta, burdinbideen inguruan materiala egon zitekeela ikusi nuen. Aldi berean, Juan Carlos García-Funesek lan penitentziarioaren inguruko doktoretza tesia bukatu zuen. Burdinbideen Artxibo Historikoarekin harremana izan genuen eta bertatik heldu zitzaigun proiektuan parte hartzeko eskaera.

Zertan datza?

RENFEk bere langileek jasan zuten errepresioaren inguruko ikerketa abiarazi nahi izan zuen, eta behin informazioa lortuta, datuak jakinarazteko webgunea sortu. Bere langileen kontrako errepresioa eta fusilatzeak interesatzen zitzaizkien gehienbat. Gurea zeharkako atala da, langile batailoiko kideak ez baitziren trenbideetako beharginak gerra baino lehen. Hala ere, lortu dute esklaboek egitasmo handi horretan euren toki edukitzea.

Horrelako egitasmoak ez dira ohikoak...

Egia esan, ez. Askotan erakundeak eta beraien politikak kritikatzen ditugu, eta hori egiten jarraitu behar dugu, baina RENFE izan da autohistoria kritikoa egin duen enpresa handi bakarra. Iritzi aldaketaren adibidea jarriko dizuet: 2008an Altsasuko Udalak burdinbideetako obretan bortxaz aritutako langileen omenez eskultura jarri nahi izan zuen herriko tren geltokian. ADIFek baimena ukatu zien eta horregatik oroigarri hori hirigunearen erdian kokatu zuten, udaletxearen aurrean. Lehen baimena ukatzen zuenak orain oroimena sustatzen du.

Aldaketa handia, beraz.

Bai, gainera webgunearen aurkezpen ekitaldian, garaiko Sustapen Ministroak, Jose Luis Abalosek, damu deklarazioak egin zituen: “Adiskidetzea atzera ez begiratzea zela uste genuen. Oker ginen”. Lehenengo aldiz, PSOEko goi kargu batek, publikoki aitortu zuen trantsizioaren memoria politika akatsa izan zela.

Lanean segitzen duzue zuen ikerketekin?

Beste gai batzuk ikertzen gabiltza eta zeharka burdinbidearena ere azaltzen da. Nafarroako Erriberan milaka bortxazko langile ibili ziren eta dokumentazio hori ez dugu topatu. Ate batzuk jotzeko ditugu oraindik, agian egunen batean sorpresaren bat egongo da.

Iazko uztailean, ARGIAren 2.880. zenbakiko orrialdeotan genuen Bego Ariznabarreta Orbea. Bere aitaren gudaritzaz ari zen, eta 1936ko Gerra Zibilean lagun egindako Aking Chan, Xangai brigadista txinatarraz ere mintzatu zitzaigun. Oraindik orain, berriz, Gasteizen hartu ditu... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

1936ko Gerran milaka haurrek Euskal Herria utzi behar izan zuten faxisten bonbetatik ihes egiteko. Frantzia, Katalunia, Belgika, Erresuma Batua, Sobietar Batasuna eta Amerikako herrialdeetara joandako horien historia jasotzeko zeregin erraldoiari ekin dio Intxorta 1937... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

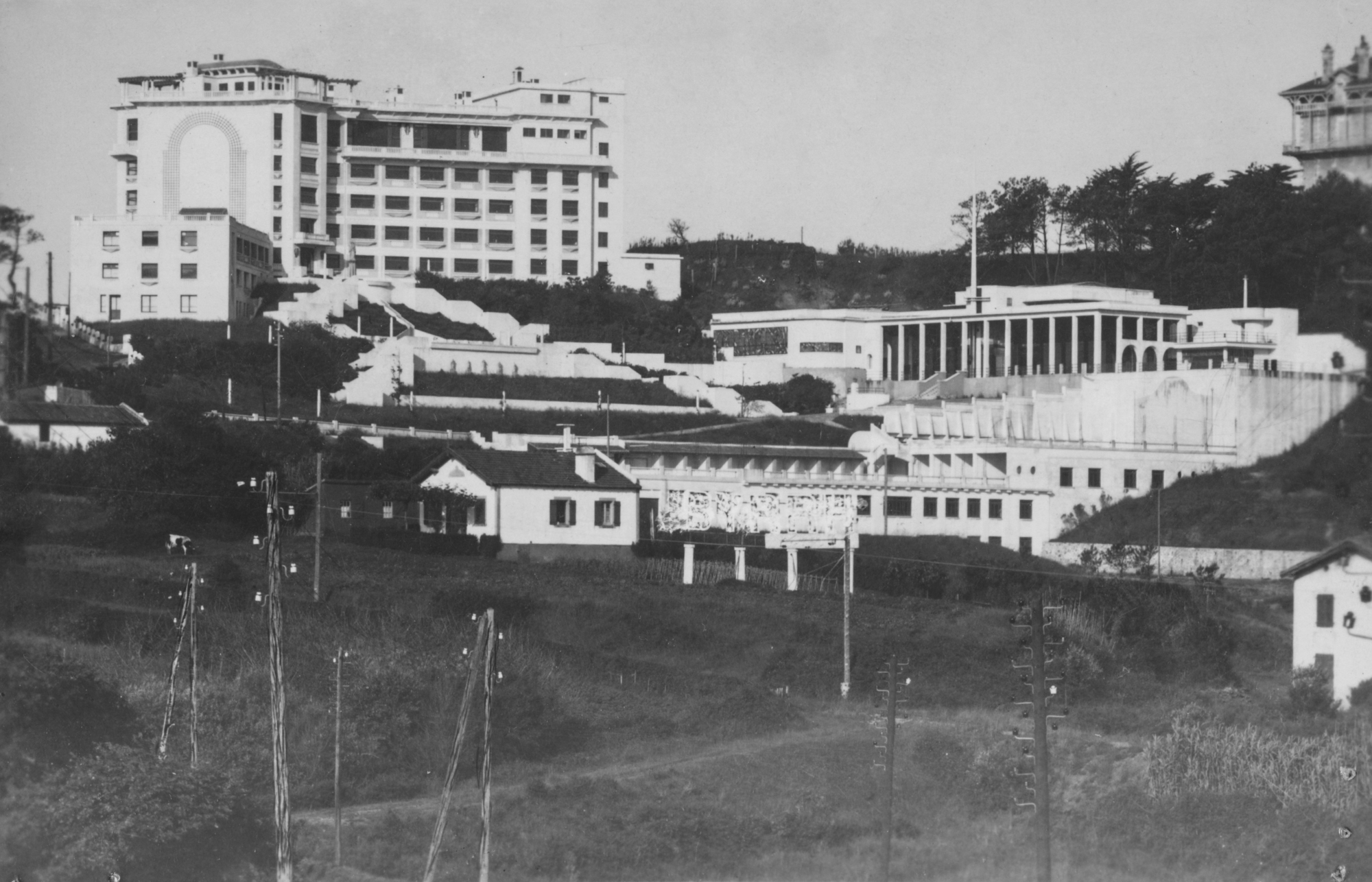

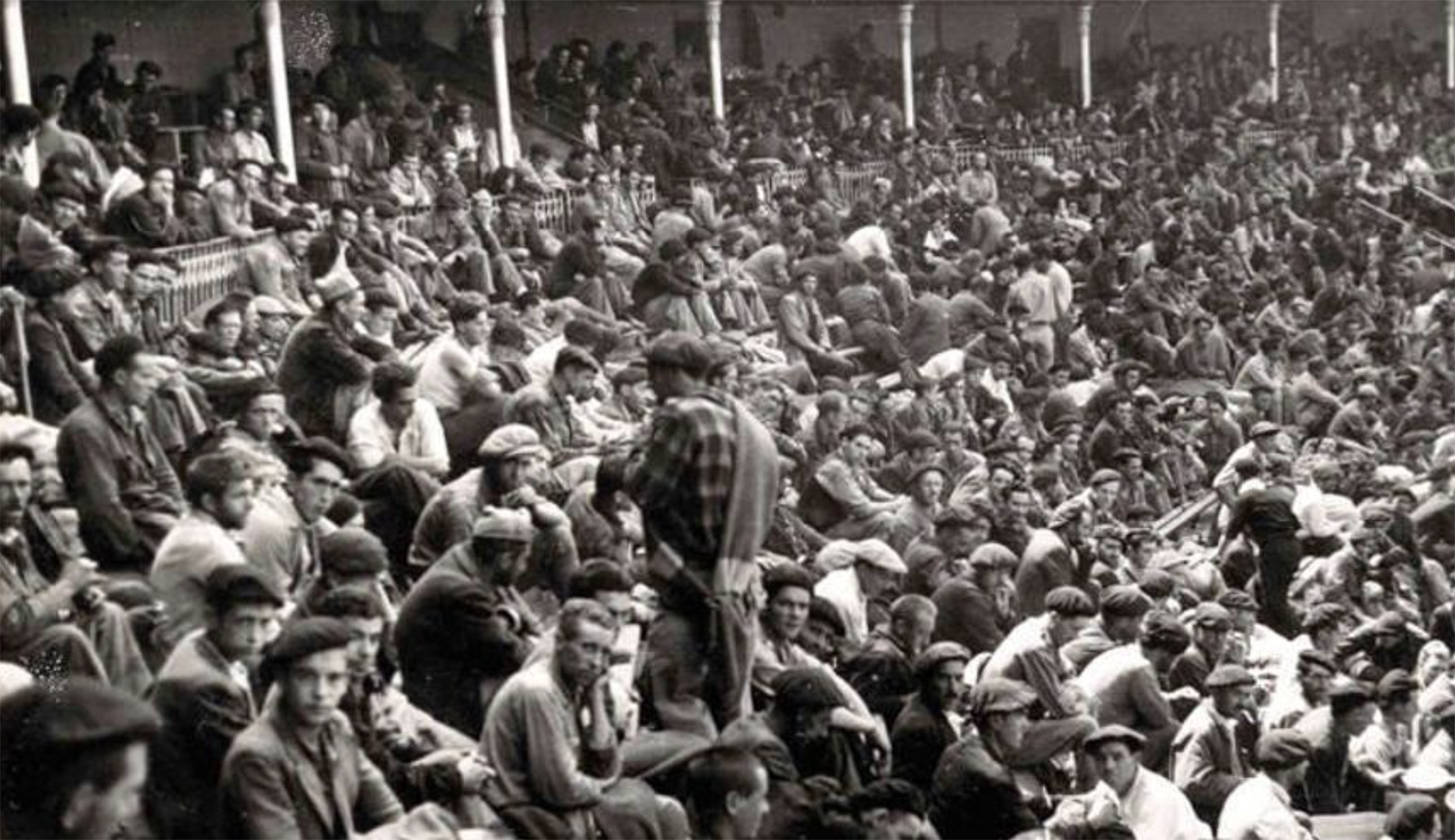

Pamplona, 1939. At the beginning of the year, the bullring in the city was used as a concentration camp by the Francoists. It was officially capable of 3,000 prisoners of war, at a time when there was no front in Navarre, so those locked up there should be regarded as prisoners... [+]

Segundo Hernandez preso anarkistaren senide Lander Garciak hunkituta hitz egin du, Ezkabatik ihes egindako gasteiztarraren gorpuzkinak jasotzerako orduan. Nafarroako Gobernuak egindako urratsa eskertuta, hamarkada luzetan pairatutako isiltasuna salatu du ekitaldian.