An exception in the history of Euskera?

- Euskera has been represented as an oral language in most cases in the past, with only a written presence and, in any case, in religious texts. On many occasions, by means of laws and impositions, but there is evidence of something else, such as the one just presented by Euskaltzaindia and the Government of Navarra: In Goizueta, more than 300 commercial cards and ferries have been found between the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries. We have been with Patxi Salaberri Zaraitegi and Juan José Zubiri who have collected and published these letters.

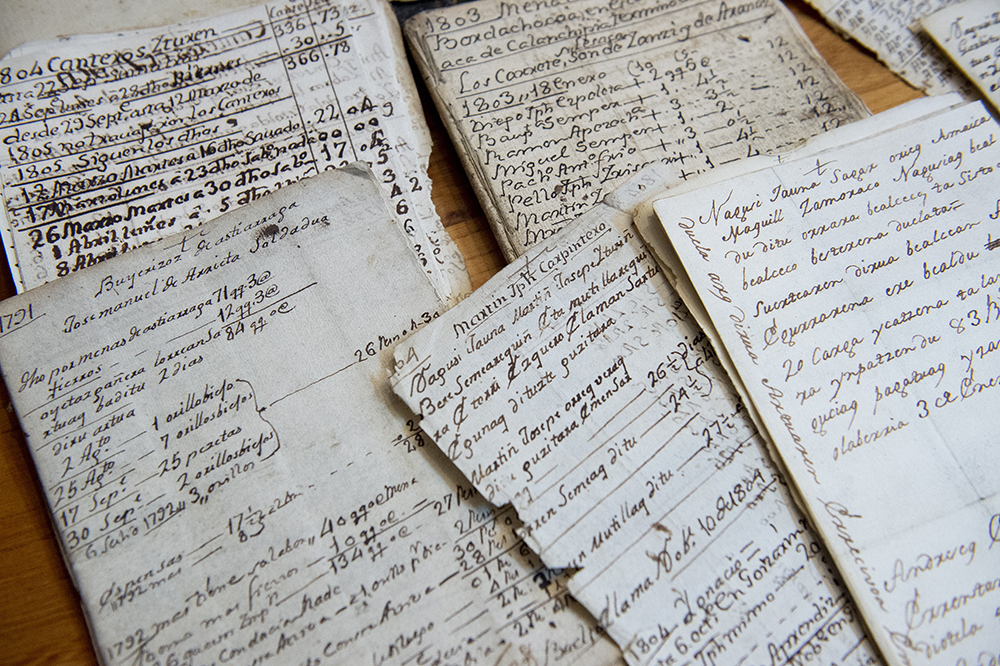

In one of the houses of Goizueta the letters have appeared, between the clothes and the old accounting papers, and have been collected in two volumes by Euskaltzaindia and the Government of Navarra, one with the letters collected and the other with its linguistic analysis. [Letters from madrugado José Ramón Minondo]. Olaberria (Oiartzun). Under the name of 1790-1807, the collection consists of letters sent by José Ramón Minondo, responsible for the Olaberria ferrería de Oiartzun, to the olajaun Juan Bautista Minondo, resident in the Goitzarin ferreria of Artikutza (Goizueta), which are mostly materials or cash accounts used in their daily activity. The publication contains letters from Oiartzun and Goizueta, but it is explained that they were also exchanged with other ferrerías from the Northern Basque Country: “They had close relationships with the ferreria of Ainhoa, that of San Juan de Luz, that of Ziburua, etc. – says Patxi Salaberri Zaraitegi, academic and author of the book. And it’s nice to see that many were in Basque.”

The letters are an “exception” depending on the people who have worked in their publication, both for their character in Basque and for their theme: “There is a rich vocabulary about the industry and the ferreries, which has worked very little in Euskera. In this sense, the letters are very important because they fill a void,” explains Salaberri. But to understand their importance, it is necessary to realize the historical moment in which they were written.

The story against itself

These were confusing times for the Basque Country at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, somewhat more than usual. On the one hand, there were explicit prohibitions for writing in Basque. This is what Salaberri says: “The President of the Academy of the Basque Language, Andrés Urrutia, stated in the presentation that during those years the Government of Spain issued a decree prohibiting the use of a language other than Spanish in commercial relations. These are not books, of course, letters, personal and without public significance. But that shows that they were Euskaldunes and that if you know how to write, they did.”

.jpg)

have appeared in the town's Paskoltzenea house. (Photo: Foku / Iñigo Uriz)

On the other hand, its influence on the recent French Revolution is undeniable. “The War of the Convention is the consequence of this revolution and all subsequent wrecks separated Ipar Euskal Herria from Hego Euskal Herria. The French army burned villages in the South, not in the North, which helped to establish what was French and Spanish. All Basques yes, but separated,” says the Basque.

Within reach of a few

Despite the limitations, it may seem barbaric to recognize the importance of such letters written in Basque, but researchers have highlighted the context. To begin with, knowing how to write: “Most did not go to school, the number of illiterates was quite large,” says Salaberri. Because knowing how to write was a matter for the wealthy or clergy at the time: “Who did you learn to read and write? Certainly the ones who had money, the high-class ones. Everyone else had to work,” explains Juan José Zubiri, a member of the Basque Language Academy and co-author of the book, along with Patxi and Iker Salaberri. In addition, those who knew how to write did not know, in most cases, how to write in Basque: “In the schools they studied in Spanish, French or Latin, at least in Basque, because it was totally forbidden.”

If those who spoke Basque wanted to write in their language, they also faced another obstacle: the lack of rules for writing in Basque. They knew the forms and rules in Spanish or French, which they studied in school in those languages, but there was no Basque: “Then there was no Euskaltzaindia, nor a unified way of writing. That’s why each of them managed as they could,” says Zubiri. This is what the letters analyzed and the methods they used to write in Basque: “José Ramón Minondo writes quite well, systematically, and has his ‘tz’ system to make ‘ts’ and ‘tt’,” the researcher explains.

These, to take into account any text in Basque of the time. But in this case, as they were commercial issues, for Zubiri the minondotarras also needed extraordinary linguistic resources. For example, to do accounts, they also studied in Spanish at school, and they found it in the letters. “When it comes to writing in Basque, the numbers or quantities are constantly passed on to Spanish. But this is still normal today among the Basques,” Salaberri said.

All these sieves have had to pass in order to write these letters in Euskera, and the subject of these texts is another: talking in Euskera about trade turns those manuscripts into a small treasure. Zubiri says: “They knew how to write priests, even the wealthy, but the latter, instead of dedicating themselves to religious issues, did business. And in this sense, Minondo’s letters are an exception, due to the issue they dealt with in Euskera”.

Researchers continually use the word “exception” and believe that this discovery will bring a small light to the secret history of the Basque Country.

The word “exception” is a constant word in the mouth of the interviewees, who believe that the discovery will bring a small light in the secret history of the Basque Country. Another aspect that has been highlighted to highlight the singularity of the texts is their number and duration. These are not the first texts in Basque found outside the religious sphere: “Ekaitz Santazilia and Mikel Taberna published an administrative text found in the Municipality of Bera. The mornings also featured the city ordinances of the 19th century... If they are like that,” says Salaberri. But it says that they are short or rare texts, and in the case of Minondo not: “Here are 318 texts, sometimes all written in Basque, something very unusual. On the one hand, the exception is that it belongs to the world of ferries and, on the other, that it is so much”.

democratic Basque

It was not an easy time to publish the Basque language in the books, as it was a privilege limited to a few texts. But because language is the people's, it's democratic. Thus, from these letters it can be concluded that the use of Euskera was very extensive. The authors studied in another language at school, but performed better in the mother tongue: “Of course they did it in Basque, we do it today, how wouldn’t they do it two hundred years ago? They were genuine Basques,” says Salaberri. Zubiri agrees with him: “We in the book have not done any socio-linguistic study, but it is to be assumed that most of the relations were produced at that time in Basque.”

It seems suspicious, but Salaberri has defended his opinion: “It is not known what the use of Euskera was like at that time. We know that in Iparralde the change coincided with the First World War, in which the Basques of the North had to head the war and in which French sentiment and language itself were reinforced. Despite being purely vasco-speakers, they felt French because they were against the Germans. That was a great incentive, in my opinion, in the French of Iparralde.” But this happened a hundred years after writing the letters. He said earlier that the Basque country predominated in both the North and the South, as well as in the area where the members of the Minondo family lived (Errenteria, Oiartzun, Irún..): “Today these peoples could be giants, but by 1800 they were smaller and relations were made in Euskera.”

In the mouths of the citizens, Euskera was the daily language, and served to “unite” both sides of the border, even through the sea. In Salaberri ' s words, the soldiers at the border were often paralyzing the goods, and in Goizueta and its surroundings there was “an escape to transport and remove the material through the Urumea”. He says that many of these relations were in Basque, and that what was a mere trade operation became a tool for the union of the Basques: “The North and South of the Basque Country appear in a way united. It’s nice to see that many relationships were in Basque, the language always helped that.”

We are seeing more and more spelling errors in the writings of social networks, not only of young people, but also of the media. Some have become so common that they hardly hurt their eyes.

In this way, we can read in Spanish many things like: "You lose a dog," "It'll be that or k... [+]

Euskaltzaindia's motto is "ekin eta jarrai" ("ekin eta jarrai"), the outlawing of Euskaltzaindia. I don't know why the Academy wasn't outlawed, all three words appeared on its logo. The allegations have been made with less - and (those of one age remember the cassette of The Mondragon... [+]

Euskararen biziberritzea Ipar Euskal Herrian jardunaldia antolatzen du ostiral honetan Baionan Euskaltzaindiak. Euskararen alde egiten dena eta ez dena eztabaidatzeko mementoa izango da. Eragileak eta politikariak bilduko dira egun osoan.

In a one-hour commute to the workplace, I am accompanied by the car radio. On yesterday's journey, I had the opportunity to enjoy a short story program, as the last port of the road, full of curves, began in Karrantza. Short legends, yes, of few words, but stories of great... [+]