What does the person who stops eating when he stops eating?

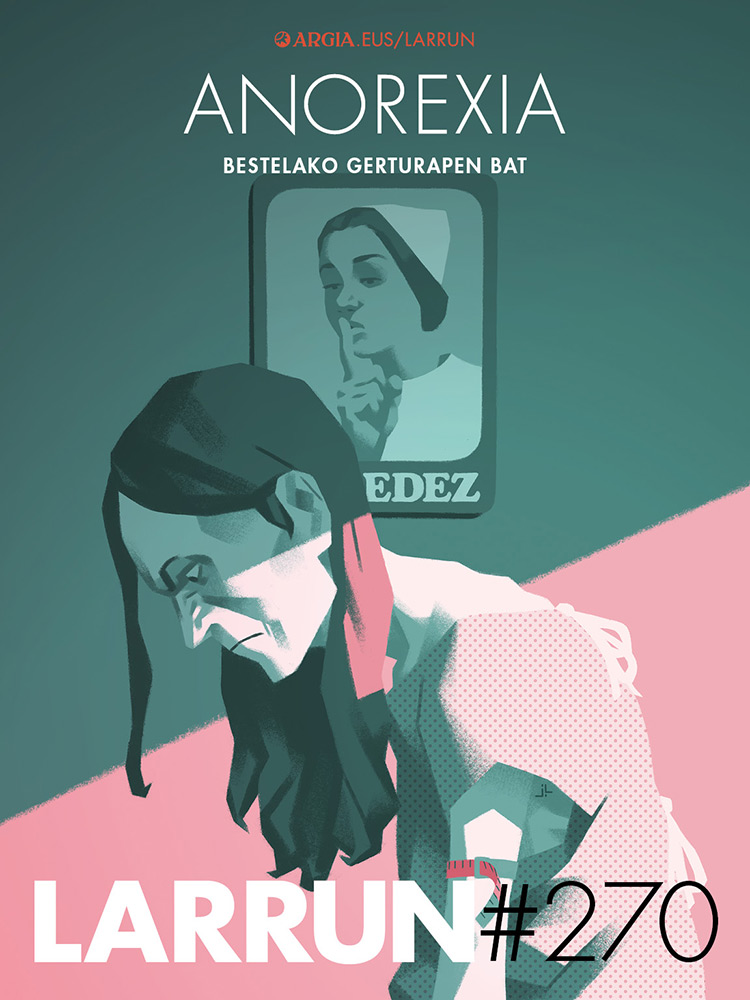

- It's a long time that people who stop voluntarily awaken the intrigue of doctors. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, fasting donors became a phenomenon that had to be analyzed closely in the eyes of soft coats; in order to clarify whether survival without food was possible or not, many of those who refused to eat – in most cases women – began to follow closely. Since then, the phenomenon has been studied by experts from different areas and has become one of the headaches of physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists and nutritionists, among others. However, most of them have drunk from the same source, and this is the origin of research that doctors began in the Modern Age. This has radically conditioned the understanding we have today of the so-called anorexia, which has been criticized by several, because it has been a dominant tendency to analyze what has given up food as an object and not as a subject with the capacity to act in front of oneself and reality, that is, as someone who, for any reason, stops eating consciously for some reason (you). Thus, the possibility of asking those who have stopped eating for the reasons they may have for it has been ruled out, and the understanding and discourse about anorexia has been imposed that little is fixed on this aspect, so that no other kind of perspective seems to be able to try to understand anorexia. On these pages we wanted to bring the issue closer through the travesías, using as a roadmap the works of several researchers and testimonies of women who have received a diagnostic anorexia at some point in their lives. What reflects a mosaic with them gives us a very different image to anorexia. The belly you're drawing can keep several clues about what you're going to scream.

Structural problems have to do with mental health and, consequently, the more entrenched the position in this structure, the less privileges it has, the more chances one has of suffering psychic. In other words, the oppressions pass the bill. In this sense, psychologist Leire Pinedo Rodríguez spoke in Larrun #268 about mental health: “If we only focus the focus of suicide on mental illness, we will not focus on other areas, and for example, not being able to lead a dignified life or lead a precarious life are risk factors.” When it comes to exploring the origin of suicides or psychic distress, since many times mental illnesses distract us from attention, as if we were faced with a single explanation in view of the complexity – or incomprehensible – of what we are studying. And so, certain ailments are individualized that do not necessarily have to be individual, inferring that instead of the context they have to do with the individual – their nature, genetics or biological factors.

To this logic is opposed the article of Carlos Cascos The commodification of mental health: it is not you, it is the system (Commodification of mental health: you are not the system), which suggests that, considering that at European level 54% of young people suffer from anxiety or depression, the one that generates figures of size is a system that must be questioned at the root. It argues that, instead of focusing on young people, it should be placed in the material and symbolic conditions of these young people. We can do the same exercise with anorexia and provide some data: if there are data that are repeated in place and year after year, 90% of the cases occur in women and the remaining 10% in men; for example, research on the profile of the user of the mental health system of Osakidetza indicates how this percentage is maintained year after year, as the variations in the data for 1995-2011 are negligible. In addition, research carried out in recent years has evidenced the discomfort that also has a great incidence in the LGTB+ group, and according to a questionnaire carried out in the United States in 2018, more than half of those aged between 13 and 24 years of this group had a diagnosis of ‘eating disorder’, with anorexia being the most frequent. And with significant data, the increase in cases of anorexia detected in the context of COVID-19 cannot go unnoticed, since only in Bizkaia have detected 153.33% more cases, according to the Report on the mental health of adolescents. The determination of gender in the development of anorexia, or the rise that the diagnoses may experience in unusual and complex contexts, among others, suggest that anorexia is also closely linked to the sociocultural context. Here, isn't it the system that needs to be questioned?

"If there are data that are repeated on site and year by year, 90% of the cases occur in women and the remaining 10% in men. In addition, research carried out in recent years has shown that it is also a discomfort with a strong impact on the LGTB+ collective"

“Under all mental illness, a social conflict is hidden,” said Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia. “We don’t lack serotonin, we are left with capitalism,” said some contemporaries who make a critical reading of health and psychology. In these pages we intend to draw from the thread of those who have pointed out that the root of many psychic sufferings is structural, an image plagued by anorexia, understanding that the one we have talked about is also closely linked to the structure and sociocultural context. At least in part, the readings on anorexia performed from different areas come to recognize that it is so, because everyone recognizes that it has a multi-causal origin and that it has influence educational, social or cultural aspects. However, researcher Eva Zafra Aparici highlights in her doctoral dissertation that, although the consensus on the multicausal origin is general, there is no consensus or consensus when it comes to determining what these factors are, “especially in social and cultural terms”. The discourse that has acquired the most strength identifies the sociocultural roots of anorexia in the weight of fashion and in the rigid aesthetic canons in function of an unattainable ideal beauty. However, if we look at the history of anorexia, it is a reading that loses consistency, since what we know as anorexia has also existed in times when there were very different ideal beauties in force. It is not a modern disease, as is often the case on many occasions. From there, the dominant discourse on anorexia has some edges that are debatable.

From sanctity to sickness

A historical review of anorexia opens the essay What you have never been told about anorexia, by the physician Paloma Gómez, who have never told you about anorexia, in order to discover from when there is an attitude to stop eating voluntarily. According to his documentation, the first documents that tell us about people who refuse to eat are those of the pre-Christian era. The Greek medicine Corpus Hipocrticum is found in the teaching pamphlet and belongs to Hippocrates de Cos (469-377 k.a. ). However, given that the lack of appetite may be due to various reasons and that it is not very clear in this sense, it cannot be concluded that the symptoms of the people who then stopped eating are similar to what we call anorexia today.

We have to take the leap to Rome in the first century to find more references to people who have stopped feeding. The Greek physician Metrodora formed a medical treatise on the diseases most suffered by women of the time, and in the chapter dedicated to young people he talks about what he called Sitergia. In Greek it means “refusal to eat”, a word he used to refer to the young Roma who stopped eating. “The main symptom was obstinate denial of food intake to maintain extreme thinness and disappearance of menstruation. This description corresponds to the characteristics attributed to the current anorexia nervosa”, reads Raquel Santiso Sanz Body, society and culture: An anthropological study of ‘eating behavior disorders’ (Body, society and culture: Anthropological study of 'eating disorders' in research work. The curiosity to know the cause of this phenomenon led Gómez to delve into the theme and conclude that those women stopped eating to get rid of their “biological destiny”. Faced with the lack of rights and freedoms of the time and forced marriages, “they had the only weapon they had to reveal: not giving children.”

.JPG)

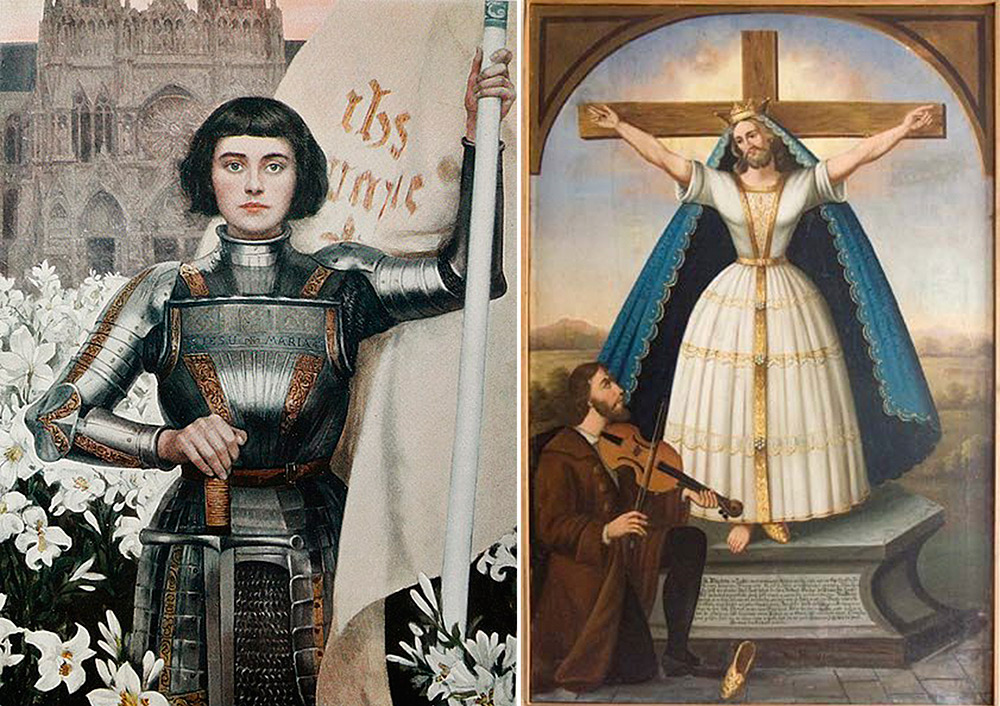

The conclusions of Gómez were identical to those of Trotula de Salerta (1110-1160), almost a millennium earlier, in a context very different from that of Metrodora, when focusing attention on the possible reasons why some women stopped eating. Christianity was expanding in Europe, and many women would start to join the Ascartic practices, bringing fasting to the extreme. Proof of this are references to young people who refuse to eat in theological literature from the 5th to 16th centuries. According to Trotula de Salero, the adolescent women who stopped eating sought to get rid of the function of creating children. And in the context of the time, moreover, far from receiving reproach back, they produced admiration. “With the guarantee of this new doctrine that values virgin women more than married women, the women of the first centuries of our age suddenly found themselves in the possibility of freeing themselves from their unworthiness and inferiority to men,” says Gómez in Anorexia nervosa: a feminist approach. On the phenomenon, the Italian historian Rudolph Bell wrote and collected the biographies of 261 Italian saints in Holy Anorexia (Santa Anorexia), all of which would meet the current diagnostic conditions to consider them anorexic. According to Bell, most medieval saints were anorexic.

"References from young people who refuse to eat can be found in theological literature from the 5th to 16th centuries. According to Trotula de Salero, the adolescent women who stopped eating sought to get rid of the function of creating children"

But how things are, from that sanctification to criminalization there was only one step. “Mistrust towards the fasting believer will grow. There will be widespread suspicion that they are Hereje because they lived from an internal fire rather than from the food of the earth,” says Santiso. At the time of inquisition, the attitude considered divine became a sign of demonization and a reason to burn in the fire. Here begins the spies of anorexium, first by the clergy, and later by the doctors.

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the secularization of society will occur, and the same will happen with the anorexic practice: those who refuse to eat will no longer bet on religious life. They will become a source of curiosity in the eyes of those who want to find reason for the phenomenon. Thus, experts from different areas will make trips to the homes of these fasting. “The supernatural causes will continue to be the main explanation, but the tension began to emerge between the magical, religious and scientific interpretations,” says Santiso. The doctors tried to analyze the phenomenon and to figure out whether it was possible to survive without food. The followings were so rigorous that, more than an observation, they can be considered as spies: in some cases, they were temporarily closed with the person who stopped eating by the doctor, in order to document all the details of the march of the same. As has been seen, the women who died as a result of a more extreme observation were quite a lot, since if the observed hang something, even if the amount is minimal, fasting was considered a fraud. Far from drawing clear conclusions from these observations, scientific theories and interpretations multiplied and, as stated by Santiso, “many of them originated the female reproductive system and the manipulative, fascinating and misleading personality of women, who sought to draw attention to this attitude”. Today, this interpretation echoes. Finally, the anorexia practice would be associated and diagnosed with hysteria until the term anorexia nervosa has been generated.

The term will be born in the nineteenth century with the stabilization of biomedical science and the rise of psychiatry. The French physician Charles Lasegue gave the name “hysterical anorexia” to the clinical description of the disease and the English psychiatrist William Withey Gull used the term “anorexia nervosa”. Both used “women’s irrational naturalness” to support their scientific reasoning. This is what Santiso explains: “They tried to unsuccessfully search for the organic causes that would explain anorexia nervosa. Then they transferred attention to the mind, attributing the origin of anorexia to the psychic state of the patients”. Through this process, anorexia became understood as a disease, and “once the term was stabilized, repression, domination and punishment were the treatment received by patients with anorexia nervosa. With them, the psychiatrization of anorexia begins”.

According to the explanations of Santiso, a “large part” of the experts who today treat anorexia, considers that people who voluntarily abandoned the term anorexia nervosa in times prior to the production of the term, could not be diagnosed as anorexia, for one reason: the fear of thickening did not determine the reasons why it did not eat. Others object to this point of view, understanding that anorexia goes hand in hand with the sociocultural context and is very sensitive to it, reacting in front of it as a chameleon; as the context changes the way of manifesting itself from anorexia. If we consider that all these cases that have been raised through the historical review follow him, we agree with the following observations made by Santiso and Gómez: the historical analysis highlights the persistence of the protests through food against those with less power, being age and gender in most of the decisive cases; and the second notes that “this is a typical manifestation of anorexia, of a young man and of a woman”.

Need to observe the meaning

It is a biomedical reading that considers anorexia as a mental illness and is diagnosed with the criteria collected in the manual of mental disorders DSM: decreased eating and consequent weight decrease, fear of gaining weight and alteration of perception of one's own weight or physical complexity. Psychoanalysts Mitchell Wilson and Umberto Galimberti point out that, however, the clinical gaze of DSM is centered on the body and is limited to observing the symptoms, regardless of the discomfort that can be kept behind them. “In this way, the symbolic and social meaning is extracted to the body, distributing the mental disorder and the social framework that generates it,” says Eugenia Gil García in his thesis Anorexia and bulimia: medical discourses and discourses of diagnosed women (Anorexia and bulimia: medical discourses and diagnosed women). At this point of departure, Gil insisted on the need to analyze the meanings of anorexic practices instead of studying them, conducting research in that direction.

Or not, from Bedi, or it will not be Gil's motivation to carry out the research in the interview offered to the program in 2019. It was the beginning of the new millennium and its initial intention was to analyze the prevalence of eating disorders in Andalusia. However, as we read on the topic to find out what the research consisted of, a critical view of the reading on the theme emerges, with the idea that what he read did not correspond to what he saw in the future. In fact, she had a teenage daughter, and two or three of her friends had been diagnosed with a feeding disorder. “I saw that these girls were neither slogans, nor frivolous, nor capricious. I wondered. What's going on here?" He took advantage of this question and decided to change the direction of research.

Between 1971 and 2003 it analyzes the medical literature on anorexia published in the Spanish State, with a clear conclusion: two discourses have been imposed on it, the nutritionist and the preventive. According to the first, the person with anorexia is capricious and psychologically weak but of great will, which leads to the end the desire to be thin. According to the second, women are more at risk of suffering discomfort due to the pressure exerted by fashion on them and the desire to be thin. That is, anorexia presents itself as a person totally dependent on the beauty canon. Gil concludes that the understanding of the malaise is based on prejudices linked to both genders, to which will be added the perspective that will deepen the prejudices at the end of the 90's: will centralize the family in the development of anorexia and will impose responsibility on the figure of the mother, responsible for the family breakdown and insufficient control of the feeding of her daughter as a result of her integration into the labor market.

"According to the philosopher, sociologist and anthropologist Bruno Latour, medical discourse will form the "black box" of anorexia, making it part of the inalienable truth of malaise"

According to the philosopher, sociologist and anthropologist Bruno Latour, the medical discourse will create the “black box” of anorexia, making it part of the irreproachable truth of malaise, of which the speeches we have just mentioned will be part, leaving aside other points of view, such as the one that the psychologist Conxa Perpiñá published in 89. For Perpigná, the pathology does not reside in the weight, but in the attitudes and beliefs surrounding it and in the “need” of the individual to reduce it. It focused primarily on the need to focus attention on meanings and not on symptoms. Gil continues his underlined path, aware of the need for a perspective that pays attention to what are going to be said about anorexic practices. Fourteen women with diagnostic anorexia were interviewed for their study. The research closes with the consequences of observing discomfort with other eyes and complexity, also accommodating the voices of those who experience anorexia in the skin.

Gil stresses that the renunciation of food is a rationally adopted decision in all analyzed cases and that it follows one objective: safety, acceptance of others and the achievement of one's own autonomy. For example, the desire to be independent is manifested time and again in the testimonies. The researcher clarifies that “the body is used as a space for presentation and representation, and the interviewees use it to improve social relationships”. Proof of this is Bethlehem or Antonia. As explained by the first, its main objective was to be good in studies of young people, so it had little relationship with those of the same age; as age increased, there was a need to be accepted of them, along with concern about diet. “I had problems in class and thought that if I slimmed down and made myself more beautiful, the next course things would leave me better,” we can read. Antonia, for her part, has as a father a man of strict discipline, who from a young age finds in his studies a field that allows him to escape his control and develop his identity. As in Bethlehem, focusing on studies will make it difficult for him to relate with them and slimmer his strategy during adolescence.

Eugenia Gil García: “The body is used as a space for presentation and representation, and the interviewees use it to improve social relationships”

Losing weight as a strategy to improve social relationships and self-assertion is, therefore, a parity among the interviewees, but not the only one. In Gil's words, all interviewees experience a conflict between the identity they should have based on the system of domination and the identity they want to build: “The interviewees perform female roles that they accept with difficulty. They experience the fissure by accepting the role according to the norm and building their own identity.” They experience decoupling in themselves, explicitly rejecting patriarchal ideology but at the same time internalizing domination: parents are not models, but figures of “independent women”, but nevertheless seek recognition from parents; they show resistance to the hegemonic model of femininity, but in turn generate conflict, stress and uncertainty, etc. Manuel's story is significant in this sense: he began fighting for his own space and autonomy before an authoritarian father, but also fulfilled his wishes, leaving the house on the excuse of his studies, but enrolling in medicine as his father wanted. He developed anorexia throughout his career.

.jpg)

“When contradictions become abrupt and unbearable, situations of stress and uncertainty can occur that produce deep discomfort. The ways of expressing this discomfort depend on the historical context,” says Gil. He points out that fasting or vomiting emerge in situations of difficult context, and that for these practices to become anorexic the individual must find in their repetition the way of expelling the tension caused by everyday situations. If they are effective in calming the tension, they allow you a sense of control over the situation, you will repeatedly resort to this solution, creating a relationship based on addiction. That is, assuming the anorexic practice.

Meanings of not eating different according to gender

The psychologist María Asunción González de Chávez acknowledges in Gil’s conclusions the indicators of the so-called “power of the weak”. According to González de Chávez, those who are subjected to the system of domination, by their subjugation, have disabilities to meet their needs orally and express their discomfort clearly, so they are forced to resort to other strategies that make up the “power of the weak”. “Only aggressiveness is manifested and imposed indirectly (…), even if it is passive and not directly, it allows to express discomfort, anger and resentment,” says Gil. The conclusions show that anorexia would also be one of the ways to externalize these feelings to women in situations of inequality; the interviewees speak through the body of what they cannot say upwards. Although in practice receivers do not interpret the message at the will of the issuer. Although in most cases they do not look at the existence of the message. .jpg)

The anthropologist Eva Zafra Aparici confirms this. After conducting observations and interviews with students in four educational centers in Catalonia, in 2007 he published the study Learning to eat: socialization processes and “Eating Behavior Disorders”. He studied whether people's socialization processes have anything to do with the attitudes and practices they develop regarding food, demonstrating that they are closely related. According to this approach, food goes beyond the nutritional scope, has a sociocultural dimension, so attitudes towards food acquire contextual meanings. In the words of Zafra: “Food does not depend only on nutrition. Eating more or less, or not eating, is also related to other areas of life, such as the family, the emotional, the economic, the political… We not only eat nutrients, but also meanings”. Thus, when analyzing why someone does not eat, Zafra argues that the first step is to contextualize this practice with the individual. Said and done, the same exercise did with a very broad collective: the data that point out that the eating practices corresponding to eating disorders are much more frequent in women, the researcher contextualized this reality. The conclusions of the study were clear: as age progressed, the more advanced the socialization process, the eating practices differ between boys and girls. Both eat in relation to satisfaction and pleasure at early ages, but as age progresses, they develop different attitudes. “It has become clear that the meaning of eating or not eating for girls and boys is different (and unequal), as is their socializing context.”

As explained in the study, this difference refers to socialization according to the binary gender standard. Because men socialize towards the public sphere and to have an active role, and the socialization of women interiorizes more complex and ambiguous messages; although some roles are breaking down – for example, today it is no longer rare for women to practice sport, and girls are taught in the kitchen less frequently than in the past, as something that belongs to them because they are women – sometimes patriarchal inertia and values linked to passivity appear. “These ‘lessons’ have social consequences and are manifested through food,” explains Zafra. Men eat until they satiate, because being more active means having an appetite, and because it's an attitude related to masculinity satiating personal whims and eating for pleasure. Among women, on the contrary, “self-control” attitudes are manifested for some or several reasons: when educated in the passive model they have a lower activity than men, they limit what they eat in order to control weight; following what they have seen at home, they have normalized the diet from a young age, or the family considers that thinness is an important value; or clarity as a criterion of recognition and taste for the fungus. In relation to the last reason, Zafra says: “We have detected that thinness is more linked to being part of a group that is considered successful than the desire to be lean.” Following what Gil has perceived, slimming is also presented here as a strategy to improve social relations.

Eva Zafra Aparici: “It has become clear that the meaning of eating or not eating for girls and boys is different (and unequal) from its socializing context”

The fear of lack of control over food is a fear for many of the women who have participated in the research, and what is behind this fear is a possible social consequence of excessive consumption: that if they get fat, they become an object of the thicket, that is, they suffer discrimination. However, in all cases this is not the reason why you choose to eat. “It can also express redemption, liberation, attention or claim of love…”, says Zafra. The case of a woman interviewed by him can be illustrative: Lucia feels overwhelmed by various aspects of life – studies, group of friends, couple, economic problems of her mother, etc. – and decides to stop eating in the face of the pressure that all this produces, as a gesture of giving in. In their words: “I stop eating when I can’t anymore, when I don’t care about everything around me, when I want to stop existing.” Zafra warns that the case is significant because it clearly indicates that many women seek redemption and release when they stop eating. “They seek liberation through food because they do not have other means or means to cope with their situation.” The refusal to eat, here, has little to do with the dependence on the mandates of fashion, and is related to the need to lead the stress of the moment or discomfort. The conclusions of Gil's research reinforce those of Zafra: the denial of food is a practice that hides multiple meanings, much more complex than the whim for the formation of a rigid aesthetic canon. The approach to anorexia should focus on them and start from the deciphering of meanings.

Limits of the nutritionist approach

At the same time that the limitation of focus on symptoms diverts attention and hinders the knowledge of the meanings that anorexia holds in the liver, neither does it favor prevention and attention. Because, if you don't decipher the meanings, you can't do either one or the other with full success. The result of the research in hand, Zafra states that this is the case in the case of prevention: in doing so from a nutritional point of view, the focus is placed on concrete positions regarding food (eating a lot or not eating anything) and prevention is oriented to avoid them. “However, ethnography has shown that this method is not enough,” he says. In his view: “The ‘feeding problems’ require being addressed and heard in a way that is very different from those considered ‘rational and objective’. We can treat them as diseases or deviations, or respond to what is being called ‘screams’.”

What is said about prevention can also be extrapolated to the realm of art, which is largely oriented to intervene on the symptoms of anorexia, and not so much on the agents, and this is done through feeding, that is, giving centrality to the nutritionist approach. In his study, Raquel Santiso stated that the main objectives of the therapies are to recover weight, to avoid the physical symptoms that pose a risk to the life of the patient and to teach to eat in a normalized way. That is, the priority is to ensure the proper functioning of the anorexium body.

If the priorities have not just attracted attention, but there is the question. If we go to the Osakidetza website, the treatment of eating disorders presented to us ranges from nutritional counseling to psychiatric assessment, medication and psychotherapy. However, although at first the gaze goes much further, Santiso insists on the words of anthropologist Mabel Gracia Arnaiz, that “treatments are considered effective if patients manage to gain weight”. Some testimonies suggest that it is like this: “I didn’t leave the entire hospital, but with a diet, and if I ate more than the diet specified, I became nervous, and I was just vomiting. I didn’t get out of the hospital,” explains Belén in an interview with María Eugenia Gil, and reports how the nutritionist focus treatment exacerbated the discomfort summarized by Charlotte Beale When Treatment Makes You Sick that we bring to these pages: The Eating Disorder Clinic (When Treatment Makes You Sick: Eating disorders clinic). There is no shortage of examples. The explanation can be kept in the following reading by Zafra: “It is increasingly recognized that sociocultural factors influence ‘eating disorders’, but there is no consensus on them and, therefore, there are no effective strategies that take these factors into account.”

Would the model of care that, far from being limited to symptoms, would permit exploring the meanings of the anorexic practice not entail the rate of perpetuation? Will the current chronification data not be a consequence of the care model that fails to give the right key?

Having said that, the paragraph cannot be closed without paying attention to data on the perpetuation of anorexia cases. The widespread belief that anorexia tends to chronification is both perceived and impossible to overcome. The widespread belief that the anoxic will have to learn to live in discomfort. This perception refers to the evolution of the cases under treatment, as the reality presented is not encouraging: “The total complement rate does not exceed 50-60% of the cases and in the case of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa the tendency to perpetuate is 20-30%”, can be read in the publication of the journal Nutrición Hospitalaria de primavera de 2018. However, it is legitimate to ask whether these data would not undergo changes if the doors were opened to the transformation of the care model. In other words, would the perpetuation rate not lead to a model of care that, far from being limited to symptoms, would permit inquiring about the meanings of the anorexic practice? Will the current chronification data not be a consequence of the care model that fails to give the right key?

In the words of Santiso: “Curing is not only about recovering a minimum weight or being able to eat, but it is necessary to resolve conflicts that use food and the body as a form of expression. Disease allows space, time and the excuse to resolve these conflicts.” What if it was as simple as serving the bellies that are drawing the matter?

When your treatment gets sick: eating disorders clinic, some episodes of Charlotte Beal's testimony:

Eight years after the ‘Treatment for Eating Disorder’, she ate worse than ever before. On the contrary, three years after leaving the ‘treatment’, food is pleasure, not a problem. Curious, right?"

«[Psychologist] sent me to the clinic nutritionist. In 30 minutes, he made me a daily feeding plan. It had to go at all costs. For breakfast, a cereal bowl and two toast. Food sandwich. At four o'clock in the afternoon, I had to eat a cereal bar. Dinner meats, rice and vegetables. Three times a week I could eat dessert. A snack (25-30 grams of nuts) was recommended before bedtime. Alcoholic beverages were allowed in very small quantities, according to the hand sheet provided to me by the nutritionist because ‘it increased the risk of attracting’ (…) I was told that leaving the snacks without making the snacks increased the risk of taking them’

“Dining under France’s skies at 11:00 p.m. was a problem, as the food plan had difficulty joining spontaneity, chaos and joy”

"During all these years my stomach was never empty"

“In fact, they told me that my thing was an eternal illness and that it could only be controlled by continuous and conscious care. I am surprised that he has risen up and pulled out forces to move forward, indoctrinated in that fictional nihilism.'

“If a meal did not comply with the food plan, it was not able to work. I didn't know who I was or where I was. That was the only thing that defined my identity."

“Everything I was told at that nutrition clinic was fiction. Nothing they recited to me had ‘repaired’ [discomfort]. Until they understood it as a meaningful expression of feelings that were unbearable to me, and not as a result of erroneous thinking patterns, I would continue to express pain through food.”

“I started not paying attention to meal times and the size of rations. I ate for pleasure only. I fasted later without fear of taking my calluses. I was drunk alone at home for the first time and for the second and third time, and that was what the pasta, the fillets and the ice cream followed; I did not eat too much, as the clinic has warned me. I allowed myself to starve to remember what it felt like. If I didn't feel like it, I didn't learn to eat. I learned that the world doesn't give up if I don't make a meal, just as I learned that eating two donuts one after the other is no problem."

“I came to this point with the help of a psychoanalyst who spoke the word ‘eating disorder’ as if I had dirty clothes in my hand to throw away as far as possible. He never punished me for not eating. He was surprised to learn that even when I wasn’t hungry I was forced to eat, because the hours said so (…) The boring terrazzo of the disease and the compulsion that used to surround the food disappeared»

From individual to collective. If we give the dimension that corresponds to anorexia, what?

Irritability, anxiety, stress, self-assertion, loss of interest in the environment, loss of sexual desire or derivation of all attention to eating. These characteristics constitute, among others, the profile of the person anorexia, as confirmed by dozens of writings on the subject and, to a large extent, as a consequence, practically the majority of the testimonies of anorexia follow the same scheme. In the list of characteristics of the anorexia profile, the possible causes of anorexia are confused with the lateral damage of fasting, as highlighted by Zafra in his study. Result: confusion between cause and effect.

“Both in the case of anorexia and bulimia, the multi-causal factors that articulate them are emphasized. Personal characteristics (low self-esteem, difficulties of integration, emotional conflicts, hypercontrol, irritability...); family conflicts; or disorders (depression, obsession, etc. ),” says Zafra. However, points out that these characteristics considered as a cause of anorexia become a consequence of anorexia considering the description of the so-called “food reduction syndrome” by the psychiatrist Gerard Apfeldofer. According to Apfeldofer, these characteristics are psychic consequences of not offering the body enough kilocalories. From this perspective, therefore, the fact that all anorexia follows the same pattern is more related to the side damage of fasting than to the possible common characteristics of individuals who develop anorexia.

.jpg)

The confusion between the factors that can trigger anorexia and the consequences of lack of food is not a small thing. As a consequence, it is “naturalized” that a certain age range and/or gender corresponds to a certain identity,” says Zafra. That is, it is concluded that the predominant profile of people suffering from anorexia - young women - is characterized by low self-esteem, a tendency to depression, etc., suggesting that the incidence of anorexia is so high in this multitudinous sector. The focus is on the individual rather than on supra-individual factors that have propitiated the development of anorexia. In this way, relating ourselves to what we said in the first pages, discomfort is individualized and, instead of the context, the personality of the individual is problematized. In other words, the structural character of anorexia is hidden. There is not much to be scrutinized to find messages that strengthen this idea; without going any further, the motto of the Association against Anorexia and Bulimia (ACAB) says: “When you don’t like it, you get sick.” According to this statement, the lack of individual self-esteem would be the cause of anorexia, while the possible causes of the lack of self-esteem are not verbal.

What happens if we change our perspective and give a structural dimension to the problem? What does anorexia point to us in relation to society and its organization? Nine out of ten cases are clearly related between discomfort and gender, which together with the high incidence in the LGTB+ group reinforces this relationship. The discomfort developed above all by women and some members of the LGTB+ group has a great chance of suffering one of the collateral damages of the gender norm, that is, patriarchal oppression; harming some men should not be an argument to refute what has been said, because, despite the privileges that the gender norm provides to men, it can also harm men, even if the possibilities of developing the discomfort are lower. Zafra reinforces the idea that arises: “Eating disorders are metaphorical expressions of identity, sexual conflicts and freedom between women and men. There is a close relationship between the development of these disorders and the conflict with the contradictory roles assigned to women in this society”.

Nine out of ten cases are clearly related between discomfort and gender, which together with the high incidence in the LGTB+ group reinforces this relationship

Giving anorexia a dimension that goes beyond the individual, in addition to pointing out the structural character of the discomfort, necessarily implies making its collective character visible. In fact, being classified as a mental illness, the person diagnosed with anorexia is usually charged with the stigma of madness, which entails attributing – to individualize – the discomfort to one’s own characteristics and carrying it hidden and secret, as if it were something personal. Santiso explains how Arta reinforces this trend: “Patients are often reminded that they are in it [under therapy] because they are sick, because they move badly and deform reality. This is a strong strategy for silencing and for them to lose authority, power and security.” This mutism in the experience of anorexia hinders the visualization of the structural character of the discomfort, as it is something that everyone lives in their loneliness, regardless of the medical group, as it is not usual to share and contrast experiences, headaches, feelings, opinions, conceptions and other experiences with or with people who are in the same situation. Even when the interaction occurs, in general, the same reading prevails and is reproduced as a common aspect of anorexic when treating mental illness. Because, if not explored enough, we are presented as a unique example the profile of anorexia that makes the dominant discourse about anorexia: the patient. Anorexian will cost you more or less to identify with it, but in the absence of more references, you will need to place yourself with more or less effort within this scheme, to give an explanation of what happens to you. Until the mutism is broken, stigma is broken and explanations are started elsewhere.

Talking about the theme without tobacco allows us to show that the experiences of anorexia come from the rigid pattern of anorexia formed by the medical literature, since in the personal experiences some nuances can be found that do not collect the medical manuals. This opens the opportunity for those who have (ha) a living anorexia to see it identified in the testimonies of others; in the symptomatological picture of a disease yes or no will have to fit more if it is more reflected in the testimony of it. It has the key to situate their experience as a consequence of a collective and, therefore, structural problem. And when we get to this point, we have the opportunity to politicize the issue: the issue is no longer a matter of madness, because we can verify its relationship with the structure, and with the place where one occupies. From this point of departure, anorexia occupies a very different place, as, as Naomi Wolf warned, “self-defense, unlike dementia, is a legitimate allegation in relation to feeding problems. Self-defense is not a stigma, while madness is shameful.” This was stated by the theorist in his essay The Beauty Myth: “Pain is real when it is possible to convince others of the existence of this pain. If no one believes in it, except the one who suffers, our pain is the madness, the hysteria or the inability we have as a woman. When we hear people with authority such as doctors, priests or psychiatrists who say that what we feel is not pain, we have learned to bow to pain.”

There is, therefore, a difference in the sense of observing and counting anorexia. Consideration of the structural character of the discomfort in the mouth, of the meanings that the anorexic practice may have, should be essential. From the words of Gil and Zafra, where the way passes to relieve the discomfort. This is how Greece Guzman comes to defend through his testimony; how did feminism help me understand my discomfort? (How has feminism helped me understand my discomfort?) Article 6 reads as follows: “What I lacked was not psychiatry, other relationships that I lacked, other narratives, other experiences and possibilities. I was lacking in politicizing my malestars and feminism has taught me to do so.” The fact of meeting and talking to women who had gone through the same life experience, along with deepening feminist theory, helped her understand her discomfort.

Greece Guzman: “What I lacked was not psychiatry, other relationships that I lacked, other narratives, other experiences and possibilities. I was lacking in politicizing my malestars and feminism has taught me to do it.”

In line with the above, Gil concluded in his study that if attention to anorexia cases drank from the feminist perspective, a very prosperous path would be opened. The integration of the gender perspective in health care would be a significant advance, as it would allow a more comprehensive understanding of anorexia and, consequently, facilitate access to well-being. In any case, it seems impossible to find the formula to end the disease, if not for the revolution of the capitalist and patriarchal system. Throughout the current social structure, anorexia agents will continue to exist and, consequently, the malestars that produce them and their channels of channeling. And feeding, as Zafra warned, “is, has been and will be a technique of expression of discomfort.” In this sense, the article The Politics that Vows (Politics that Vows), published in Pikara Magazine, speaks of the need to legitimize the use of food to channel discomfort until structural changes take place: “Our hysteria is to legitimize our methods to channel the harm that this damn society causes us.” It seems reasonable to do so while minimizing collateral damage to the so-called anorexia and increasing the recovery rate while improving care. As Anari sings, among all the ways of escaping, because each of us has his own. The challenge would be to put an end to flight needs, not to prevent escapes. Just as anorexia is an expression and solution in bad ways metaphorically speaking, the closure of this escape route would amount to an ambush. And that, of course, has little help. Instead of disobeying the belly that is blocking the outings and starving, let's look at the attention. By deciphering what the one who stops eating says he stops eating, there's the key.