"Santi Cobos highlights the bridges between social and political prisoners"

- Santi Cobos Fernández (León, Castilla, 1968) has been in prison for 25 years, half of his life. Reformatory, juvenile prison, for seniors. Most years classified as FIES prisoners in extreme conditions of isolation and mistreatment. ARGIA journalist Zigor Olabarria has collected his experiences in the book Txori urdin to complete his account of the prison system and the culture of punishment.

Cobos has tried to flee on several occasions: through the door, the wall, the roof, the court, kidnapped by the penitentiary or by the police. On the way he has made a great friendship with the Basque political prisoners, who will take over the reader. In 2011 he was released on parole, but in June 2021 he was imprisoned as a result of a fortuitous confrontation outside a bar. He tells the prison's experiences first in the book published by ARGIA.

From Santi Cobos' experiences, the book portrays the penitentiary system in crude form.

Precisely, on the basis of what Santi Cobos lived in prison, my intention was to reflect on the penitentiary system, which I consider necessary to go further into the subject. I have worked in the Salhaketa association and in the associations for the Basque political prisoners, I have some sensitivity in relation to the issue. I have always felt that the bridges or the relationships between social and political prisoners were less than they should have been, or that they have not emerged. Cobos also talks about these bridges in the book.

He mentioned social and political prisoners. In our case, surely, the experiences and demands of these seconds are better known.

That's right. In Euskal Herria, prison is very present, but in most cases we are talking about what internalizes political prisoners, which can be called “our penitentiary center”. The reality of “normal” and “social” prisoners is less well known. The term “social prisoner” was created in the 1980s by the collective of Spanish prisoners COPEL to overcome the term “common prisoner” depoliticized. “We are social prisoners, our being in jail has a social origin,” they said. They gave political meaning to the prison. Time has passed, but there is still a certain lack of sensitivity towards people in prison, despite the crime they have committed. The prison is a centre for the reduction of persons.

At the beginning of the book, Cobos speaks of its origin.

This part helps, on the one hand, to show who Santi is. On the other hand, there are books that capture the experiences of other social prisoners, such as Huye, man, flee and Ángel ‘Patxi’, of the Galician Xosé Tarrio, as On two sides of the wall, also of the Catalan Zamoro, also of the FIES, of the flight and of the children, of whom officials and judges have been kidnapped and of whom they have been imprisoned are very hard. To understand the penitentiary system, telling it was fundamental.

He said that they have suffered heavy jails, including Cobos...

Their personal history is part of a collective history. In the early 1990s, some 60-80 prisoners, especially conflicting, who organized escapes or riots, were welcomed and subjected to a series of measures. These are the ones known as FIES, even though FIES is legally something else. They suffered a heartbreaking isolation and terrible torture. Most of them have died in the same prison due to illness, insanity or suicide. I have the feeling that those who have survived have been the most politicised, the ones who have sought a political cause to what has been suffered. That's where we can put Santi. In this sense, he reports that his relationship with political prisoners has helped to explain politically to those who lived instinctively. He realized that the one who was living had a sphere that was not so personal, but socio-political.

Attention is drawn to the impunity of those who perpetuate the prison system, despite the fact that the prisoners have been put to death.

I've talked to several prisoners about this, very crude stories I knew, but when Santi started telling me what I had lived in jail, in the isolation or in the reformation of minors, I mixed my belly. There are exceptions between officials, and he recognizes them in the book, but ... Look also at the doctors, how they become part of the system. And Santi, without ever appearing as a victim, reports his actions, the pain caused, but also says in the book: “I did all this to achieve freedom. And on the other hand, I would tell the officials, the officials, the attempted escape, the kidnappings, the boys... that I was paying all of them, but for the torture and ill-treatment that I suffered, that the doctors would tell the officials how to beat them without killing me... that no one pays for it.” This is the logic of the system.

To finish his book he had to go to jail to visit Cobos.

Yes, most of the interviews were recorded on the street in the autumn of 2020, but last June they returned to prison unexpectedly. Before in Valencia, now in Zaballa, I have made a couple of visits and we have exchanged letters to agree details about the book and the presentation.

It seems that the objective is social reintegration.

In the penitentiary discourse, this word often appears to justify its existence. There is talk of punishment, but we are told that the perpetrator of the crime has an inclusion problem, that he does not understand or accept the codes of society, that he is not integrated, because he has values that do not correspond to drugs, to monetary accounts or to society. The approach is very contradictory, because you say that a person has problems with insertion, and at the same time isolates him from society as punishment. You get into a space where the norms of life are absolutely opposed to those of the outside, which infantilizes you. The more socialization problem, the more punishment, the more time outside society. Theoretically, it aims at reinsertion, but the opposite is true. It makes you more economically vulnerable, it cuts off your relationships with your family, with your friends... It is absurd. Most people recognize that from every prison it is a failure in terms of reinsertion or non-repetition of crimes, but no one disputes it.

To rejoice some of the experiences that Cobos tells in his book, the escapes, the torture suffered, seem to be taken out of a film...

In the book, on the one hand, it counts very eye-catching, spectacular things. For me, the age of minors, the reformatory, the psychiatric module -- all of that is terrible. Or the kidnapping of the Zamora official to escape, a shooting at the Gijón court, where a police officer was killed and the police were wounded...

There are very bloody passages, let us say, that are the torture and the mistreatment it is suffering. Besides all this, it tells what is a FIES file, what it is to spend days in isolation, without hours of patio... Also, when it comes time to leave prison, how is the process to follow to banish those tools of violent hatred that the prisoner has assumed to survive; or others of tinted humor, such as the interview with a prosecutor of the National Court of Spain. Cobos is accused of forming an anarchist cell, and his conversation with the prosecutor is completely surreal. There is also room for reflection, not only with a cultured political discourse, but with what happens in jail with sexuality, senses, feelings...

To survive inside the prison, “the inmate should not be a hunting but a predator.”

That's what he says, or you're a hunting piece, or a predator. On the one hand, you have to prove that you're a predator so that no one will oppose you. But on the other hand, that -- and beatings, isolation -- arouses hatred in you, leads you to consider violence as a point of arrival, and you have to strive not to limit yourself to it, maintain solidarity between members and values, behave tenderly -- not to become a product of jail. This tension relates to the title Blue Bird, extracted from a poem by Bukowski that recited to me in an interview: how to harden to survive, without giving up tenderness at once.

But prison is nothing more than a reflection of society, more radical but faithful. To be a hunter or a predator, to have to camouflage sensitivity to poverty or injustice to energize everyday life, to use hatred and violence, not to fight the higher but the next ... Those of us who live on the streets in freedom – or, as Sarri said, in the large prison – also have the same “adaptive” attitudes, do not think that we are better than prisoners. It would be interesting to read Santi's testimony as a mirror.

It talks long and hard about the large amount of legal drugs that are consumed in prison.

I have heard from many prisoners that the introduction of television in every cell and the promotion of the use of legal drugs (Tranquimazin-eta) was the way to put an end to care or solidarity between them and to end conflicts.

Former political prisoners Otxoa de Retana and Gorka Lazkano have written the prologue, Salhaketa hitzostea... The book is partly collective, although its main protagonist is Santi Cobos.

As one of Santi's values, it seemed nice to me to build a bridge between political and social prisoners. In addition, I personally, as in the center of the jail, had a special illusion of being born from the jail. That is why we have also brought to the book the illustration made by the prisoner Itziar Moreno. My job is to sort out Santi's voice. It often happens that whites talk about racists, men of women -- and in this case, we're on the street of jail. I wanted to avoid it as much as possible.

Santi Cobos

"I needed to flush laughter after so many years of prison suit."

Zigor Olabarria Oleaga

(This interview is by letter, Santi Cobos answers questions from Zigor Olabarria from Zaballa in early November)

Before, they have proposed to collect in a book the avatars of your life. Why now? What's your motivation?

Yes, I have been proposed several times. One of the main reasons for giving the yes has been the possibility of doing so through recorded interviews, for their martyrdom, which has had to listen and transcribe everything. From the 15th year of imprisonment, after many writings, I started to pick up the pen, and the truth is that I have not yet reconciled with him.

I have the need and desire to empty laughter, after so many years of troop in the prison system. In the book I presented many of the things I denounced and denounced them long ago in the courts, many were archived without punishing anyone, in most cases I did not receive an answer either. I wanted to contribute to the list of prisoners who have brought their experiences to the book. From reading these books it is clear that prisons are not five-star hotels sold by their managers.

He has spoken to me about prison and what he has experienced with hatred and crudety, but also with humor, or with social and political reflections ...

In short, because prison is not the world of ideas, but a reality of life, in my case multiannual, and that gives for many and diverse experiences. For some prisoners, prison has a very different meaning than I give it. It may seem hard to believe, but jail can also create customs and “comforts.” Unfortunately or luckily, I have never been able to live like this and I have paid dearly.

He was born in the Castilian city of León. What is your link to Euskal Herria?

Great affection. I made a friendship with the Basque political prisoners in prison. Once on the street, here I have received affection and understanding difficult to find in many other places. The stigma of being in prison is very real, but in Euskal Herria, on the contrary, I felt supported and protected. It's my favorite land, it makes me feel good, I have friends there, especially in Vitoria. That's why they also want to learn their language.

With the book you want to reflect on the penitentiary system beyond counting your life. That is why I also wanted it to be published in the context in which the CAV has received the transfer of prisons. Do you expect any improvement? Are there alternatives to the prison?

The truth is that, despite the comments, I do not expect any significant change. I am very concerned about the lack of regulation when it comes to cutting rights in jail. As I'm seeing, COVID-19 has become a blank cheque to further reduce the few rights we have that we are forced to live here. If, at least, all this is compensated in some way by a greater promotion of permits, conditional freedoms or the third grade.

You're the protagonist of the book, but you won't be able to be physically in the presentation. Is it worth you?

The truth is that it gives me great anger, because I thought I was going to be among others and not locked up here. I demand, however, that everything that is done be accompanied by grape juice and barley and adequate food. And not taking advantage of the day to make without me a memorable orgy, even in the Basque Country... A strong embrace of solidarity for all, health and freedom!

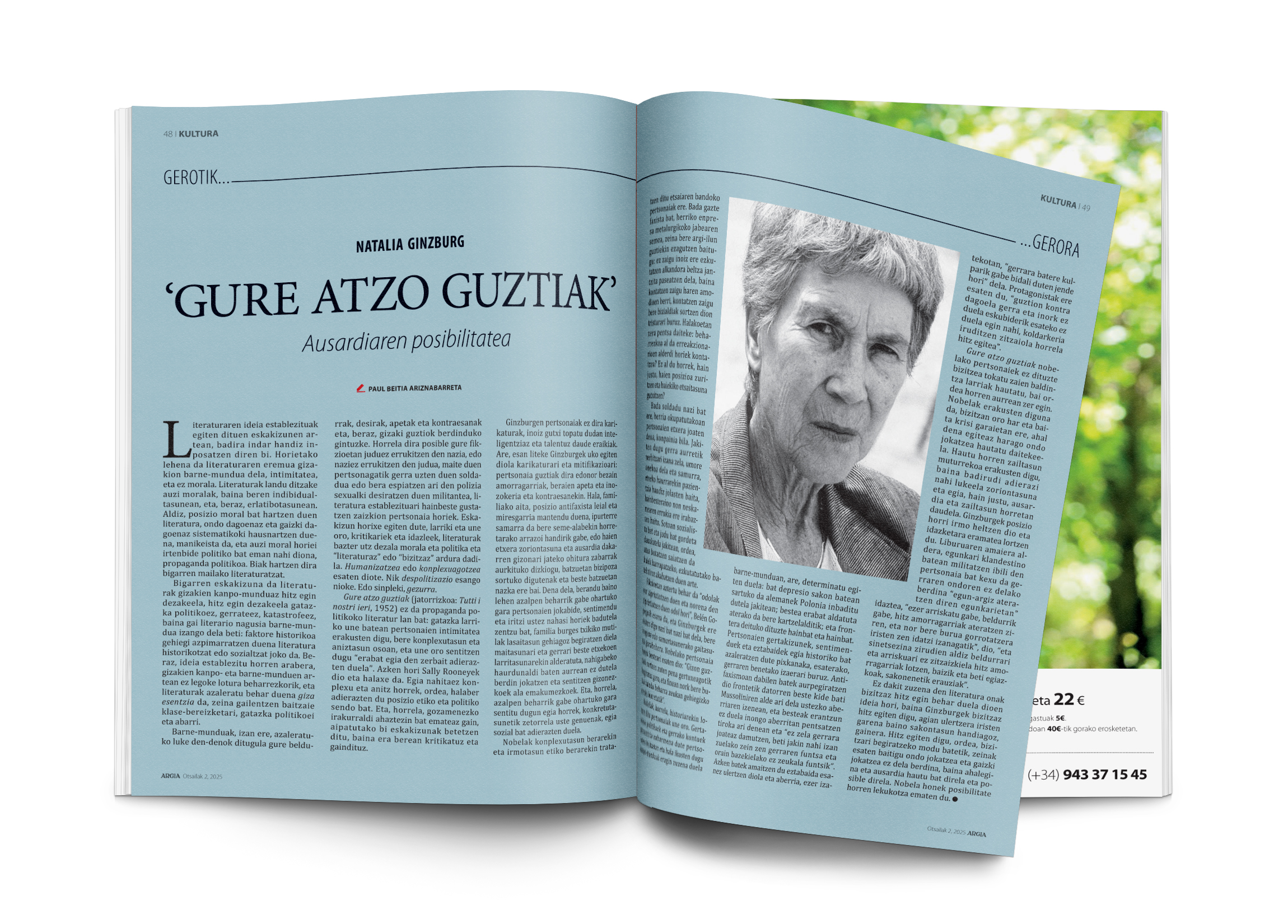

Literaturaren ideia establezituak egiten dituen eskakizunen artean, badira indar handiz inposatzen diren bi. Horietako lehena da literaturaren eremua gizakion barne-mundua dela, intimitatea, eta ez morala. Literaturak landu ditzake auzi moralak, baina beren indibidualtasunean,... [+]

Behin batean, gazterik, gidoi nagusia betetzea egokitu zitzaion. Elbira Zipitriaren ikasle izanak, ikastolen mugimendu berriarekin bat egin zuen. Irakasle izan zen artisau baino lehen. Gero, eskulturgile. Egun, musika jotzen du, bere gogoz eta bere buruarentzat. Eta beti, eta 35... [+]

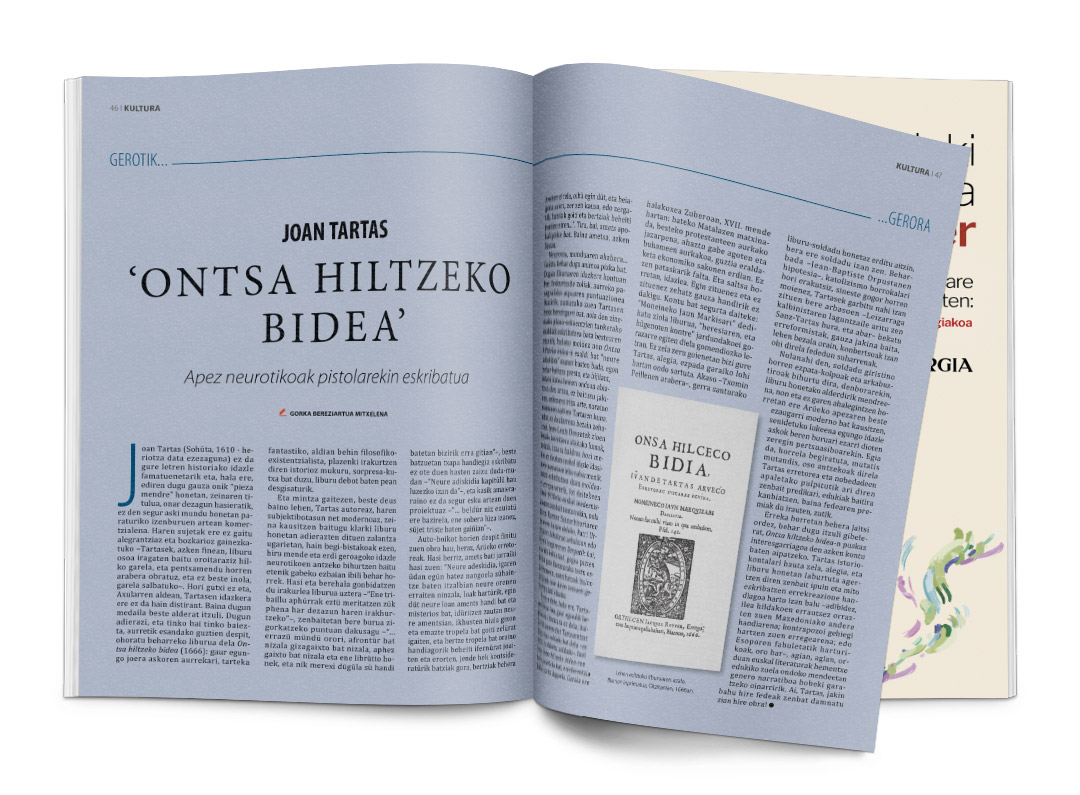

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]