“The housing problem in Bilbao is not solved at all”

- Historian Iñigo López Simón first became acquainted with the slums of Bilbao during the thesis. The thesis, however, referred to something else, and only from the surface was the new discovery addressed. Now, thanks to the Tene Mujika scholarship, he has published in a Bilbao cottage (Elkar, 2021) a book he wanted to write “for a long time”. He analyzed the municipal archive, read the censuses and researches, collected testimonies from the neighbors who lived in the houses and, finally, took advantage to bring the book the photographs of the magnificent archive of Floren Carrón and the hamlets of Gabriel Aresti.

When and how did the phenomenon of the slums of Bilbao begin?

The cabins have always been in Bilbao. The medieval city had no place for everyone, because there is never room for the poor and the marginalized, and in the Modern Age there were also cabins or other precarious housing inside and outside the city wall. In the years 1940 to 1960, however, the phenomenon increased due to the concurrence of a series of concrete circumstances: Bilbao and Bizkaia became industrialized in the 19th century, more than other places and before, and although the process remained with the civil war, it recovered very quickly. It is true that the post-war period was very harsh – hunger, repression – but the industry grew rapidly and there was a need for labour. The Franco government made a lot of propaganda about this, saying that in Bizkaia there was work for everyone. The number of people who came to Bilbao in response to this call was very high.

There was work, but there was no house.

That's it. There were few houses, the ones that were expensive, and the process of building the new houses was very slow. Three or four families lived in many houses: the situation, conditions and congestion were imagined.

And people started building the casetas.

From the 1940s he went to the City Hall requesting a license for the construction of a house, as the City Hall heard that he gave it, although it was not true. Over the years, the phenomenon accelerated enormously, and by 1955 it was a serious problem, visible from anywhere in the city.

In the book he mentions data and concrete quantities, and he has drawn .jpg) my attention to what he says in a footnote: That 10% of the Bilbao workforce lived in the casetas.

my attention to what he says in a footnote: That 10% of the Bilbao workforce lived in the casetas.

There are two very important documents there. In 1955, the City Council created a census in which 33 neighborhoods appeared. Later, in 1960, two Deusto students conducted a new study in which 6,000 casetas, some 26,000 people, were counted. It's a stack. Imagine today 26,000 people living in Bilbao in such a situation. We are not able to represent it.

Another fact known thanks to the Patrons: People born in Euskal Herria also lived in the cottages.

Yes, about 15% were from Bizkaia, many of them coming from Arratia, for example. There were also those from Gipuzkoa, Navarra and Álava.

In addition to analyzing files and research, he has collected testimonies from people who lived in the houses.

For me, that's the most interesting thing. The documents found in the files are official and they serve us to build the story, but I didn't want to make a cold history book. I wanted to tell people's feelings, views and experiences. Let the book be starred by those who lived in the casetas. I've collected testimonies, most of Uretamendi. It's been easy, because when Uretamendi's houses were demolished, the new houses were built there, and most of the population stayed there. However, with the exception of two people, all of whom I interviewed were children at that time and have given me the vision of a child. If I had interviewed her parents, I would have received a different perspective.

She has dedicated a separate section to women in the cottages. Why?

History has always been very patriarchal and Eurocentric, and those of us who make history have to prove that history is not exclusive to men. On the other hand, women were by far the ones who spent more time in the neighborhood. Here are very significant statistics: taking off the hours of sleep, men spent one or two hours a day in the caset neighborhood between the week. Women, on the other hand, came out very few: they sought water, they bought it and they ran out. So if I have to talk about the slums in the house, I'll have to talk about the ones who spent more hours there.

"Taking off the hours of sleep, the men spent one or two hours a day in the caset's neighborhood between the week. Women, on the other hand, came out very few: looking for water, buying and finishing"

And he has devoted another section to the Roma.

Like women, the Roma community has been marginalised because of its Roma status. As I have spoken to the etxolakide payos, men and women, I would also like to speak to the Gypsy ethxolakide to tell you their story. I have told her story, but from my position of privilege and from my whiteness. In the case of women, I have been able to construct a more honest account with their testimonies. But as far as the Roma are concerned, they are a little snug. I tried to talk to the Gypsies who lived in the neighborhoods, getting in touch with the Gypsy associations, but in the end I did not succeed. I have no problem, it seems to me to be an absolutely legitimate option. However, as the Spanish version will be published, I will try again.

How did the Bilbao City Hall begin to look at the situation after several years of ignorance?

In 1955 he first appeared in the press and some priests began to denounce the situation. Following this double complaint, the City Hall began to think that it might have to do something, but the problem – contrary to what was advocated by Franco – was that the Franco State was very weak; the repression was very harsh, that is true, but the State itself is very weak. It was all plugging, the mayors of Bilbao were the old names, they weren't prepared people, and there was no money to have solid structures. However, with housing they had the same problem in Madrid, Barcelona and Seville, and in the 1950s the Franco government began to carry out a series of promotions combining public and private money, and they began to build houses for all these workers. It was a policy at the state level.

.jpg)

In Bilbao, the Otxarkoaga neighborhood was built to channel the problem.

With the help of the Housing Ministry of Madrid, they got some money and started the project: they built the whole neighborhood in just one year, from 1960 to 1961. The premises were very clear: as cheap as possible, as soon as possible. Thus, they built a totally precarious neighborhood – without asphalting the streets, with a single access road, without lighting, without gardens…. According to design, cinema, schools, markets and I don't know how many things there would be, because they only built the church and police station. A cement island on the slopes of the mountain, three kilometers from the city. Three kilometres in which there was nothing but mud, in which the inhabitants of the slums got in.

One of the interviewees reports the breakdown of networks among neighbors.

Yes, they put them in the apartments as they got to Otxarkoaga, and all of a sudden they lived in huge skyscrapers, they didn't know the neighbors and there was no place to join, if it wasn't a police station. Until 1966, they didn't rebuild relationships within the neighborhood, they lost a few years. However, Otxarkoaga has been, along with Rekalde, one of the most combative neighborhoods in Bilbao. It's had a reputation for crime, but it's a neighborhood with a lot of consciousness and workers' pride, and I think that's what emerged in the slums. In the slums they had to be able to organise themselves because the city council did not listen to them or offer anything, and I believe that this boom, which seems to be very Basque, but which also the models do, has been very key – among many other factors, of course – to understanding the movement in the neighbourhood that has followed in Bilbao.

"Otxarkoaga has had a reputation for crime, but it's a neighborhood with great worker awareness and pride, and I think that's what emerged in the slums."

When he says that he also wants to make the implications of the phenomenon appear, does he mean that?

What I wanted to assert is the importance of these people in Bilbao. When talking about the topic, it is quoted as an anecdotal thing. But the footprint that these people have left in the city is obvious, and we have to accept it. It looks like the casetas disappeared and it's over, in 1961 it's all over. No, those people continued in Bilbao and their children have continued here, they have established their place and their roots here, they have participated in demonstrations, they have come into contact, they have come to San Mamés to watch matches, they have worked in workshops here… And as this there are thousands of more stories, like that of the San Francisco neighborhood, which you also have to tell, because they are bilbainos too, and they also want to talk about brilliant things and things. We also have to talk about mud, because this city is also made of mud.

In conclusion, I should like to ask you about the present. Are there currently houses in Bilbao?

This year, in January, the days after the snow, the Municipal Police shot down some houses in the park of Etxeberria, inhabited by some Maghreb, and later demolished other houses located under the bridge of Euskalduna, also inhabited by young Maghreb people. Today there's a big housing problem in Bilbao, there's a lot of evictions, there's a lot of evictions, the rents go up a lot; we've had a break for gentrification for COVID-19, but again a lot of tourists are coming to the city and the young people have nowhere to live. The phenomenon, of course, isn't the same as the time, because history doesn't repeat itself as it is, but it follows the problem, and there's no affordable housing for everyone, and there are people who still live in the bellies.

When I interviewed the caset members, they've talked proudly about their neighborhood, their life and what they've done, but that doesn't mean that what's happened has to be romantic or something anecdotal or folkloric. We must understand the reasons and the implications of what has happened, and be aware that the housing problem is by no means solved in Bilbao.

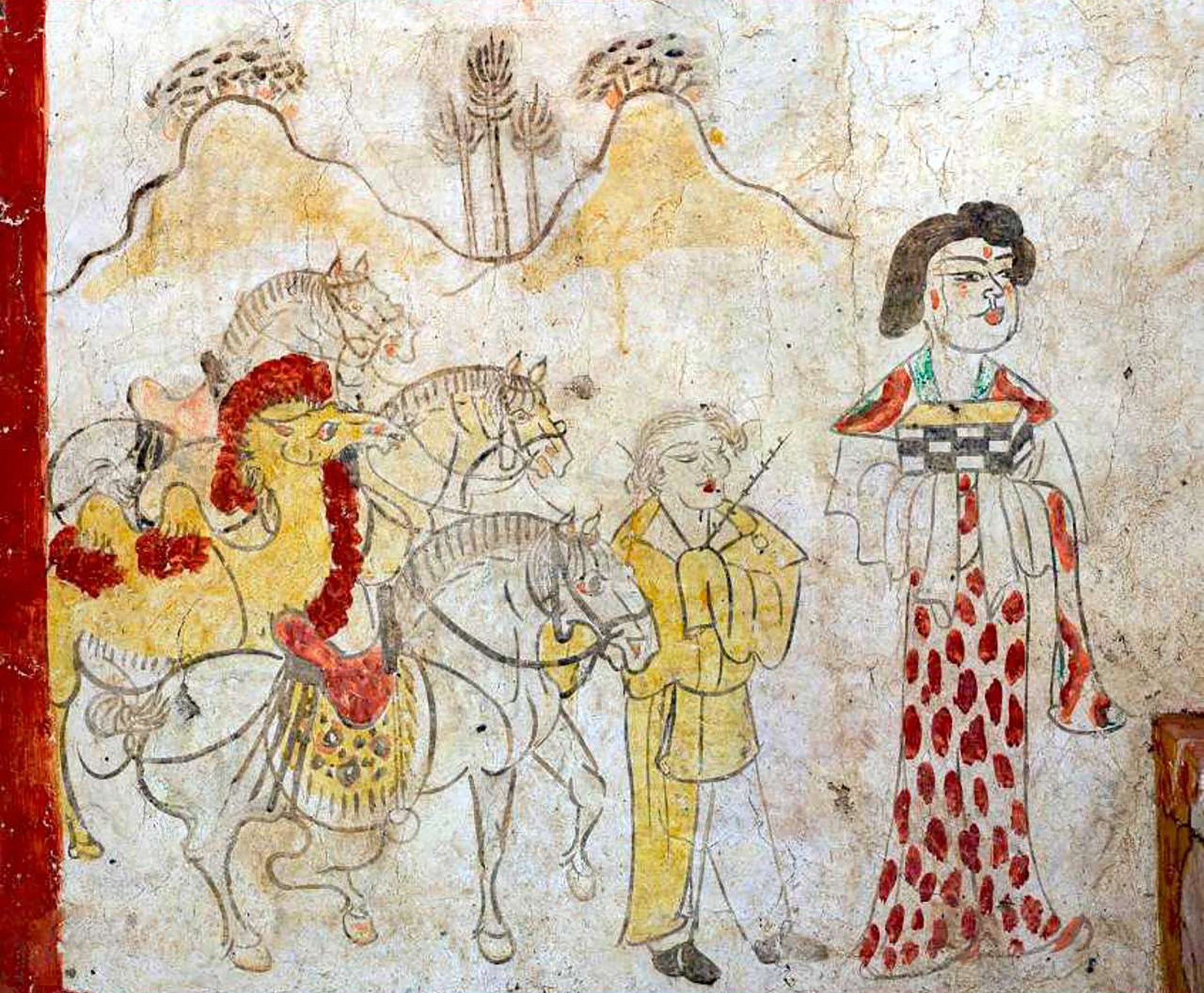

In the Chinese province of Shanxi, in a tomb of the Tang dynasty, paintings depicting scenes from the daily lives of the dead are found. In one of these scenes a blonde man appears. Looking at the color of the hair and the facial expression, archaeologists who have studied the... [+]

Carthage, from B.C. Around the 814. The Phoenicians founded a colony and the dominant civilization in the eastern Mediterranean spread to the west. Two and a half centuries later, with the decline of the Phoenician metropolis of Tyre, Carthage became independent and its... [+]

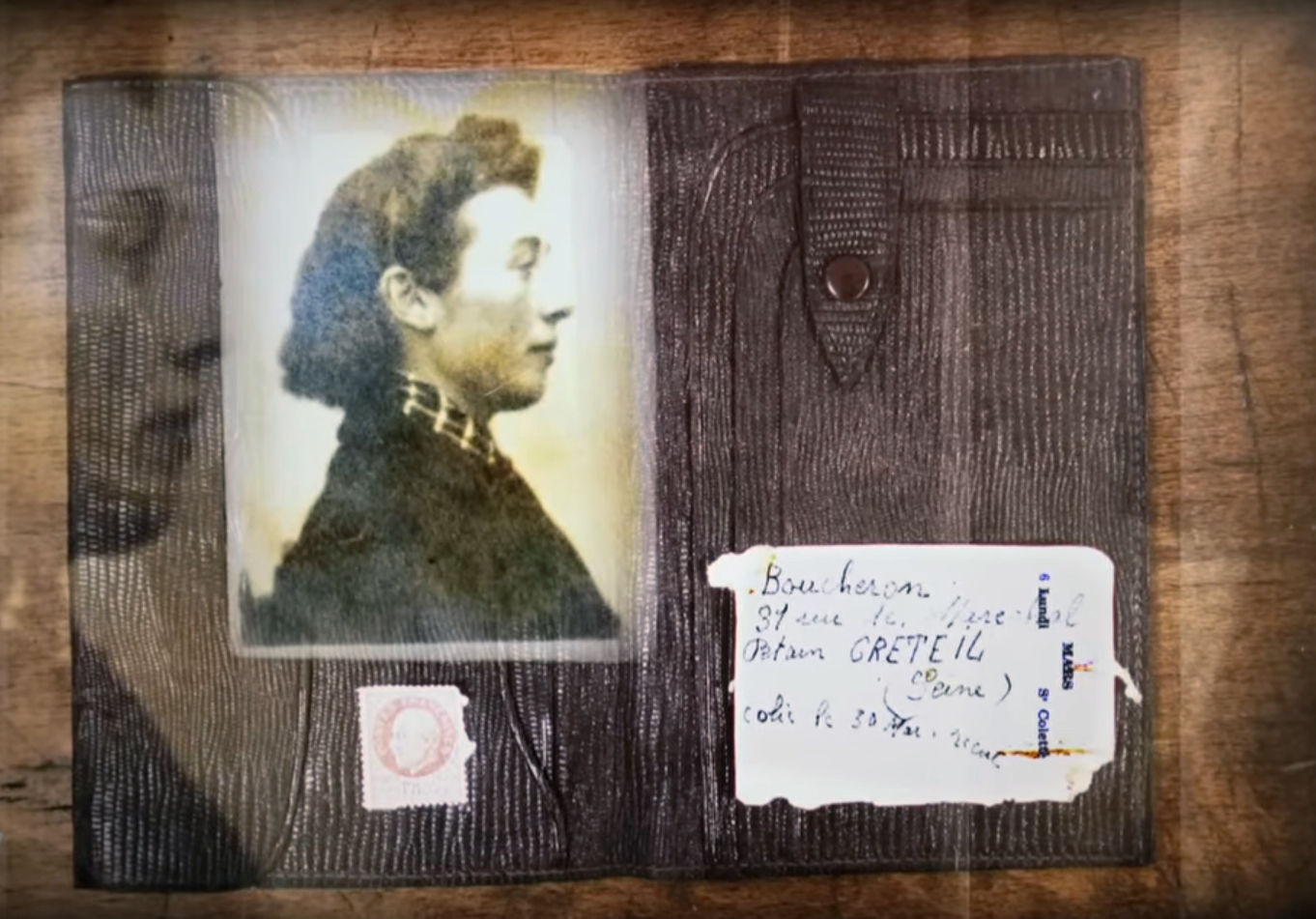

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

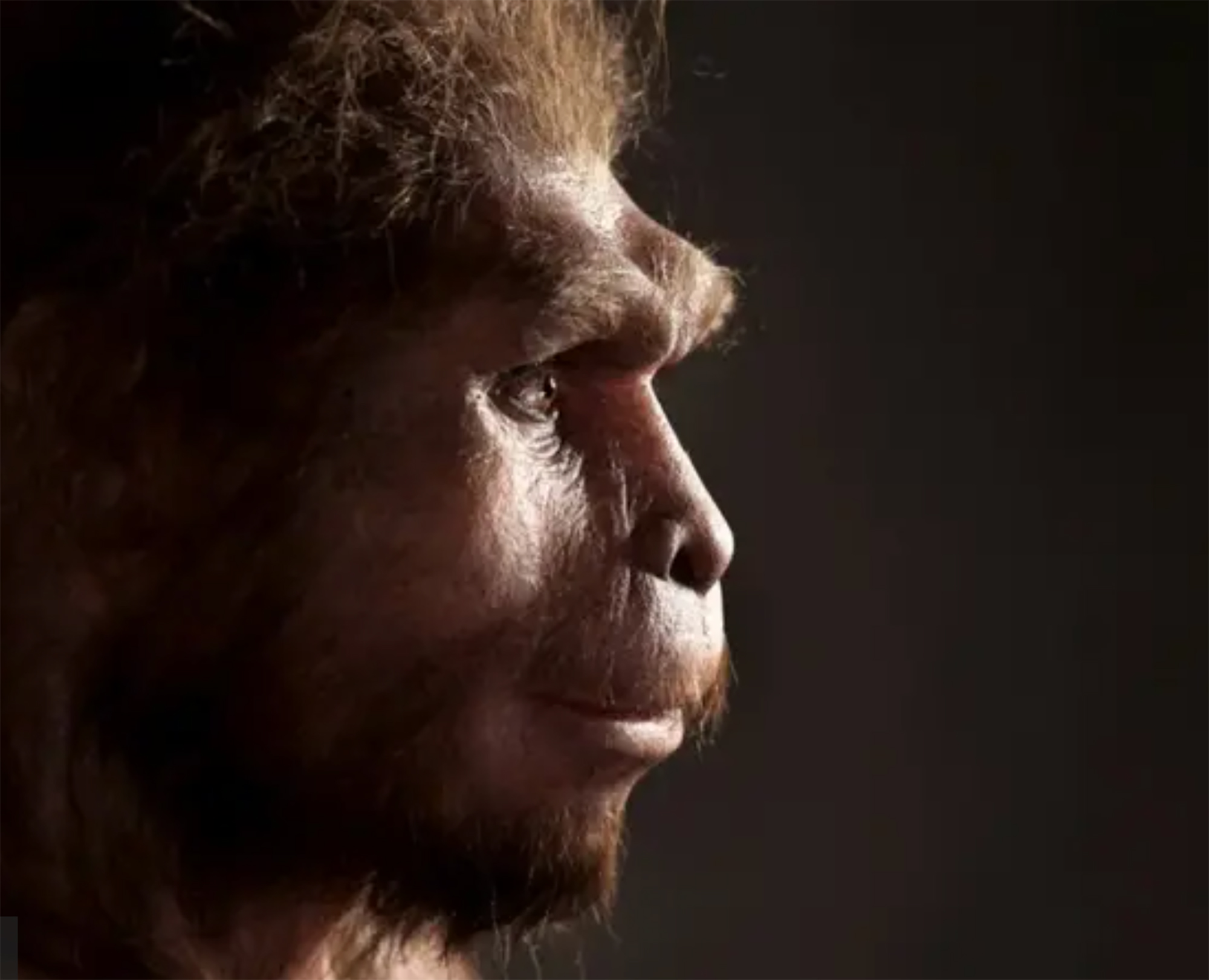

Rudolf Botha hizkuntzalari hegoafrikarrak hipotesi bat bota berri du Homo erectus-i buruz: espezieak ahozko komunikazio moduren bat garatu zuen duela milioi bat urte baino gehiago. Homo sapiens-a da, dakigunez, hitz egiteko gai den espezie bakarra eta, beraz, hortik... [+]

Böblingen, Holy Roman Empire, 12 May 1525. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg overthrew the Württemberg insurgent peasants. Three days later, on 15 May, Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Saxony joined forces to crush the Thuringian rebels in Frankenhausen, killing some 5,000 peasants... [+]

During the renovation of a sports field in the Simmering district of Vienna, a mass grave with 150 bodies was discovered in October 2024. They conclude that they were Roman legionnaires and A.D. They died around 100 years ago. Or rather, they were killed.

The bodies were buried... [+]

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1930. The U.S. Congress passed the Tariff Act. It is also known as the Smoot-Hawley Act because it was promoted by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley.

The law raised import tax limits for about 900 products by 40% to 60% in order to... [+]