Salmon in the Basque Country: fish and heritage

- Salmon has a long history rope in the Basque Country. He has created many stories, from Prehistory to the present day. Their fishing has been of great socio-economic importance, and so the rules for their regulation emerged. Then came the infringements, the conflicts between citizens and peoples, the conflicts and, in some cases, the murders. In the struggle for the continuity of Atlantic salmon in our rivers, the dissemination to society of the stories and events that have been going on over the centuries is an almost essential task. Salmon, in addition to a fish, is heritage.

A prehistoric drawing, the English king Edward I medieval, the bourgeoisies of Baiona, the mayors of Hondarribia and San Sebastián, the baserritarras and syros of the Urumea shore, the canonigo of Roncesvalles and the commander of Marina. It seems incredible, but there have been those who have linked them throughout history. Today, in Basque society it is hardly given importance, but it still retains a corner in old documents and in the memory of many older people: it is salmon. Because this fish, closer to Norway than to its rivers, has taken its place in our history in the current image of the Basques.

If salmon had no choice but to fight the stream and the open sea throughout its life cycle, it had to fight year after year against fishing with scaffolding, nets and rods, as well as against the impacts of the human being on their place of residence over the past centuries. Now that we are committed to restoring salmon stocks, it is important to talk about their ecological value. In addition, its value as a social heritage should be added. Fishing for the first Bidasoa salmon is but one of the traces of the relationship that has historically been maintained between salmon and Basque society. Let us therefore launch the network into old documents and interviews, and let us see what salmon fishing brings to us.

MAN AND SALMON: THE TWENTY-FIRST

PREHISTORY MENDERA In

the north of the Iberian Peninsula, vestiges of the human and salmon relationship have been found throughout history in various areas. Thus, in the caves of Aizpitarte, in the Urumea valley, there have been bones or branches, and hooks with fish thorns. This shows, among other things, that fishing was already a prehistoric activity, along with fruit harvesting and hunting.

The Magdalenian artists left on their drawings 14,000 years ago images of salmon, along with other animals that hunted and fished. We have a good example of this in the cave of Ekain, in the basin of the Deba. There is a drawing that shows the image of a fish. It is the image of

a salmon made by men prehistóricos.De the drawings made by the hands of the prehistoric man in the cave to the old documents, and from these to the memory of many witnesses who still live, the long history of salmon has come to us jumping.

.jpg)

SPECIALISED FISHING MODALITY:

For

centuries, salmon fishing was carried out on a large scale on the Basque coast, through a trap called "nasa". The representations of these elements are common in the ancient maps of the Basque coast as V-shaped structures that cross rivers from side to side. Its design was based on the knowledge of the biological cycle of salmon: knowing that adults go up the river, the fundamental thing was to hinder its passage through the introduction of wooden rods in the bottom of the rivers or estuaries and the construction of networks of branches between them. Thus, the fish entered a funnel shaped route and the fishermen captured the aisa.

The construction and maintenance of these elements required investment in work and resources, not of any kind, especially in areas with high water flows. Therefore, the platforms, besides having specialized production structures, were also instruments to structure power relations that allowed centralizing fishery resources and establishing inclusion/exclusion dynamics within local communities.

The oldest mentions in the Middle Ages are the oldest ones in salmon fishing with

Nasa in Baiona. In the thirteenth century, the port of Bayonne was an important shopping centre within the duchy of Aquitaine and, therefore, the kingdom of England. Most of the goods were transported by water, first by sea and along the long estuary of Aturri, to the lands of the interior of Gascuña; or to Erro upstairs, to Lapurdi and to Navarra. Thus, the city tried to protect its interests against those who hindered freedom of navigation. These included the platforms for salmon fishing, which caused problems in upstream and downstream movements.

The platforms, besides having specialized production structures, were at the same time tools to structure the power relations that allowed the centralization of fishery resources and establish inclusion/exclusion dynamics within local communities.

The oldest known platform was under the castle of Gixun, next to the island of Mirepeix, near the confluence of Atur and Biduze. Edward I.ak of England was sold in 1277 to the noble Arnaut Saubainhac of Baiona. In Errobi, Edward II.ak authorized the cure Gilen Sensac de Dax in 1289 for the construction of a new structure near the port of Berriozar. Both decisions sparked urban protests between Baiona's merchants and poor fishermen, and in 1295 the king had to send the Edmond Lancaster to mediate. According to the agreement reached, the nasa owners had to reduce the width of their structures, leaving some of the rivers free for navigation. Furthermore, between 25 December and 24 June, fishing was banned and excise duties on fish salmon would be applied.

.jpg)

Under these conditions, the road was open to the stabilization of platforms and the construction of new ones. In 1309 the Biele de Baiona family obtained permission for the installation of a platform in waters prior to Ahurti. However, Piarres-Arnaut Biel built a large structure that closed the entire estuary, allowing him to earn an annual income of 1,000 pounds, in exchange for sunk several boats and drown several men. A group led by the subainhact attacked the houses of the bielletics and burned the platform. After several incidents, Edward II.ak confirmed the ownership of the platform to Piarres-Arnaut in 1320, always with a ban on abuse.

The pier of Mirepeix was sold in 1339 by Amanieu Sabainago to Piarres Albret, the new lord of the castle of Gixun. The new owner seems to have profited from the structure to ask for tolls from traders who hindered navigation and crossed the river; in the face of the Bayonese protests, he had to order two years later the restoration of the state of Edward II.ak. In the Lower Middle Ages, the control of the platform was achieved by several nobles, among which was Gerard Tartas, owner in 1372, and Karlos Beaumont, bishop of Navarra in 1409. In 1582 he was in the hands of the Agaramont lineage of Bidaxun.

The situation changed substantially after the change of direction of the Ria de Aturri in 1578. Apart from the former mouth of the Port-d’Albret (today Vieux-Boucau, Landak), a new mouth opened between Anglet and Tarnoze, offering the city a much more direct connection with the sea. With this, the traffic from the river network would also accelerate significantly, and the platforms only hindered this trend. In 1584, advised by engineer Luis Foix, the Bordeaux Parliament ordered the dissolution of all salmon docks.

.jpg)

In lower Bidasoa, the

salmon platforms formed the centre of the tension between commercial and fishing activities. According to the urban letter of 1203, the property of all the ria and its resources corresponded to the village of Hondarribia, but the town council had to negotiate with the local lords the exercise of these rights. Thus, in 1299 he signed an agreement with the lord of the house Lastaola de Irún, which could maintain the platform that Juan Martín de Lastaola had in the Bidasoa, leaving free the third part of the estuary for navigation, to protect the traffic that came from Navarra. Upon the death of the lord, the property of the platform was to be received by the prior of the monastery of Zuberoa.

The City Hall of Hondarribia also had its own platform in the waters of the Bidasoa, located on the river Elorregi. Being away from the villa, it seems that the management of this structure caused him headaches, since the neighborhoods of Irún, Urruña and Biriatou fishing without permission in the area, without rights. Thus, in 1489, an agreement was signed with the Capital Domenja of the Buniort house of Biriatou, which, in exchange for taking care of the platform, will receive annually an economic and salmon income.

The control of the platforms played an important role in the tension environment experienced by Bajo Bidasoa at the end of the Middle Ages. Guided by the Urtubia house of Urruña, in 1509 the inhabitants of Lapurdi rejected that Hondarribia had full ownership of the estuary and began to sail and fish. The Town Hall accused the Irunanians who had the Elorregi leased platform of having taken the situation because “they have allowed the puppies to cast nets and catch fish, although it has never been done.” The environment was rapidly complicated, immersing the two sides in retaliation and a spiral counter-retaliation. Among other things, the Hondarribiarras attacked the monastery of Zuberoa and set fire to its platform alleging that being in the intertidal zone violated its jurisdiction. In response, the robbers dismantled the Elorregi platform. Finally, the intervention of both the Gipuzkoa corrector and the Senescal de Baiona calmed the environment, since in 1511 the restoration of the situation was ordered.

However, in 1532 the relatives of Domenja Capitals reported that the City of Hondarribia was not paying the rent agreed in 1489. As a result, the Buniortans felt free to break the pact and in 1533 a new platform was formed in the Alunda area. Hondarribia sued for violation of his jurisdiction, but the Lords of Biriatou received the support of Mrs. de Urtubia, committing themselves to destroy Elorregi's platform in case of damage caused by the structure of Alunda. The villa had to put armed men guarding the platform day and night.

The riots didn't end there. In 1573, the Irundarras built a platform next to the Behobia Pass, claiming that they had already had them and that they had the same right as the Labortans. In the spring of 1574 they began fishing salmon, but Hondarribia immediately denounced them and the Royal Council ordered the withdrawal of the structure in September of the same year.

.jpg)

LOCAL RULES, RELATIONS AND CONFLICTS The regulations on

the Platforms were not the same throughout the Basque coast. In Bizkaia, the Old Smoker established fishing freedom in the 15th century. The platforms clashed with this principle, as they could serve as an instrument to achieve a monopoly on fishing, so that these elements would disappear from the Biscayan landscape. In Gipuzkoa, in the Deba and Oiartzun rivers, local regulations prohibited the establishment of centralized fishing structures from the Low Middle Ages. Also in the Urumea, the municipalities of Donostia-San Sebastian and Hernani granted salmon fishing licenses up to 1564 under public auction, but from that year it was released to all neighbors.

In the other estuaries of both Lapurdi and Gipuzkoa, on the contrary, the platforms continued to be part of the daily landscape and there were few conflicts in their surroundings.

In Bizkaia,

the Old Smoker established

fishing freedom in the 15th century. The platforms clashed with this principle, as they could serve as an instrument to achieve a monopoly on fishing, so that these elements would disappear from the Biscayan landscape.

Oria: the platforms everywhere is the

Ria del Oria, perhaps the one that shows the highest concentration of nasa in the Basque coast during the Modern Age. It should be noted that the Andatza and Iria Mountains of the southern estuary were owned by the Collegiate of Roncesvalles between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. Therefore, the Pyrenean cannigos also had to do with the salmon fishing of the estuary. In 1518, for example, between the monastery where the lawsuit took place and the Municipality of Orio, there was the adaptation of the platform found in the marshes of Itzao. Although the ruling recognized the Oriotarras as the property of all the River Darisees, it made the marsh available to Roncesvalles, whose installation required the connection of both banks, who were basically condemned to understand each other.

The community of Aginaga also had its own kingdoms. In the 16th century, both the Prize and the platforms of Arruarte were rented in 1562 and 1580, among others, in order to pay off their debts. At the same time, the tower houses of Ham and Atxega also had their own dársenas, while the Gironde platform (next to the current island of Nasazar) was distributed among several owners.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the number of nasa was increasing throughout the lower course of the Oria: Aginaga, Usurbil, Zubieta, Lasarte and even Villabona. In addition to the municipal institutions, they were built by jauntxos, owners of shipyards, ferrerías or, simply, private investors, demonstrating that salmon fishing was a high-performance activity. There were also few conflicts; under the mandate of the General Boards of Gipuzkoa, to guarantee navigation it was essential to leave at least one third of the river free, and the standard was not always met.

Urola: the dock, although not in the case

of the Urola, the municipalities of Zumaia and Getaria agreed in 1416 the freedom of navigation and fishing of the inhabitants of both localities in the estuary. Accordingly, Zumaia's neighbors undertook to dismantle the existing platforms and not to make new ones in the future, ratifying the Municipal Ordinances of 1584.

However, the rule only affected the mouth of the estuary; towards the interior, the City of Zumaia had its own platform on the banks of Oikia, which was a source of conflict with the inhabitants of this neighborhood. In 1610, for example, the Dornutegi housekeeper was accused of damaging the platform and was fined a great deal. In 1680 it was Oikia’s vicar that built its own platform, and the town hall sued the Gipuzkoa corrector alleging that salmon fishing was a municipal monopoly. By the 18th century, on the contrary, references to the platforms of the Urola disappear.

Bidasoa: a rigid monopoly in

the Bidasoa, the City of Hondarribia defended for almost four hundred years the monopoly offered by the Elorregi platform (XV-XIX. centuries). Like all other public goods, the management of the structure was rented annually. In the public auction, an administrator was appointed to pay an income for the right to catch salmon. In addition, it had to sell fish at prices valued in the market of the villa and deliver to the City Hall several specimens throughout the year for the festivities.

It was also the responsibility of the administrator to guarantee the right to the monopoly of the platform, preventing those who wanted to fish in the area from passing. He sometimes had to denounce attempts to build new springs, including 1771 against the Irunans and 1797 against the Urrugnans. On other occasions, those who obstructed the platform, as well as those who fished in the Bidasoa with rods or links, should be persecuted. Tensions were frequent with the owners of the house Aruntz de Biriatou, to which the City Hall paid a rent in exchange for placing the platform on its grounds, but in 1770 and 1774 they requested that this amount be increased. In 1788, the steers denounced that the homeowner did not allow them to stabilize the platform on their grounds. Faced with the economic losses that this caused, the City Hall had to reduce the rent of the platform by a quarter.

Urumea: The competition for the installation and exploitation of

salmon platforms of the Urumea estuary during salmon fishing from the Santa Catalina Bridge of San Sebastián was in the hands of the municipalities of Donostia-San Sebastián and Hernani in the 16th century, and in exchange for an income in the attempt. The situation turned in 1564, when the two municipalities opened up to all neighbours the possibility of fishing salmon and the monopolies of the past were suspended.

The new regulations allowed salmon fishing to all the rich and poor neighbours of the river, from San Sebastian to Goizueta, but also raised new problems. On the one hand, the pressure on the species increased until its conservation was questioned. In a report prepared in 1769, the Town Hall of Hernani proposed banning salmon fishing from October to January, at laying time, while in the rest of the months, although fishing is allowed, fishing could only be done with bait or grille, and the nets should have certain measures to prevent catching too small fish and closing the entire width of the rivers. The platforms would therefore no longer be allowed in the waters of the Urumea.

.jpg)

what was at the Ezio mill in Hernani. / Source: Hernani Municipal Archive

On the other hand, conflicts between citizens and peoples also increased. In 1816, for example, in Hernani he was a lawsuit against Pascual Zuaznabar and other citizens. Reason: Because of the fishing problems in the Urumea River, there was one dead and one wounded after a debate. In 1824, for their part, the anger occurred among the peoples of the Urumea Valley. Representatives of the municipalities of Goizueta, Arano and Hernani, including the mayors, met with representatives of the City Hall of Donostia-San Sebastián in the Plaza de Loiola (Donostia-San Sebastián) and a representative of the Canonigos of Roncesvalles, owned by the Artikutza site and the monastery of Discurarbe. The first three peoples complained that in San Sebastian and Astigarraga the platforms that had stalls to catch salmon did not allow the fish to go up the river. This caused two major damage: on the one hand, families living in the Urumea above and engaged in salmon fishing could not work. On the other hand, by catching the salmon from the sea to the bank, the fish did not lay eggs in the high regatta of the Urumea and thus avoid future salmon in the Urumea. This would damage their economy and their environment, jeopardising the future of fish in the Urumea River.

In 1841, Hernani City Hall denounced several residents of Astigarraga for the installation of a platform occupying the entire river in front of the Olatxo farmhouse. They responded by attacking, both at the Santa Catalina Bridge in San Sebastian and at Hernani, between the Ezio Mill and the Pikoaga Ferreria, by placing similar structures. In 1846 there was a similar denunciation as a result of a salmon fishery with links in the Ergobi pass; and in 1868, by another platform located opposite the Txurriategi farmhouse of San Sebastián.

The complaint of seventeen Donostiarras who, years later, in 1879, were engaged in salmon fishing is also well known. They were concerned that the Navy commander banned salmon fishing on the city's Santa Catalina Bridge. The signatories assured that salmon fishing had been practised for years, which for the majority was the sole breadwinner of the family. The ban on salmon fishing on the Santa Catalina Bridge was based on the fact that the mouth of the Ría del Urumea was less than 500 metres away. However, the signatories argued that they had measured it and that it was 577 meters away. In other words, they had the right to fish.

As if that were not enough, the document submitted to the City Hall of Donostia-San Sebastián reported that in the Osiñaga district of Hernani there was also a parapet in the form of a trap for the capture of salmon that did not comply with the law, and that gave all the details adding a nice hand drawing. In the Ezio mill of Hernani there were two platforms in favor, which allowed their owners to receive all the salmon that were introduced. According to the fishermen of San Sebastian, salmon could not cross them and could only overcome them when the waters were growing. In short, the platform caused problems for the salmon to lay their eggs at the root. The mill also had a water reservoir that allowed catching salmon or salmon pups born in the river. The Donostian fishermen said that the ban on fishing on the Santa Catalina Bridge was based on injustice. He was told that the Hernani mill was doing more damage and that nothing was done against it. In addition, they showed their complaint, as they had to fish according to the tides, while the Hernaniarras could do it all year round.

The documents indicate, therefore, that conflicts and anger were not very common among salmon fishermen and peoples. Because salmon fishing was not a whim of leisure, but a trade of support for many families.

THE TIMES OF LIBERALIZATION

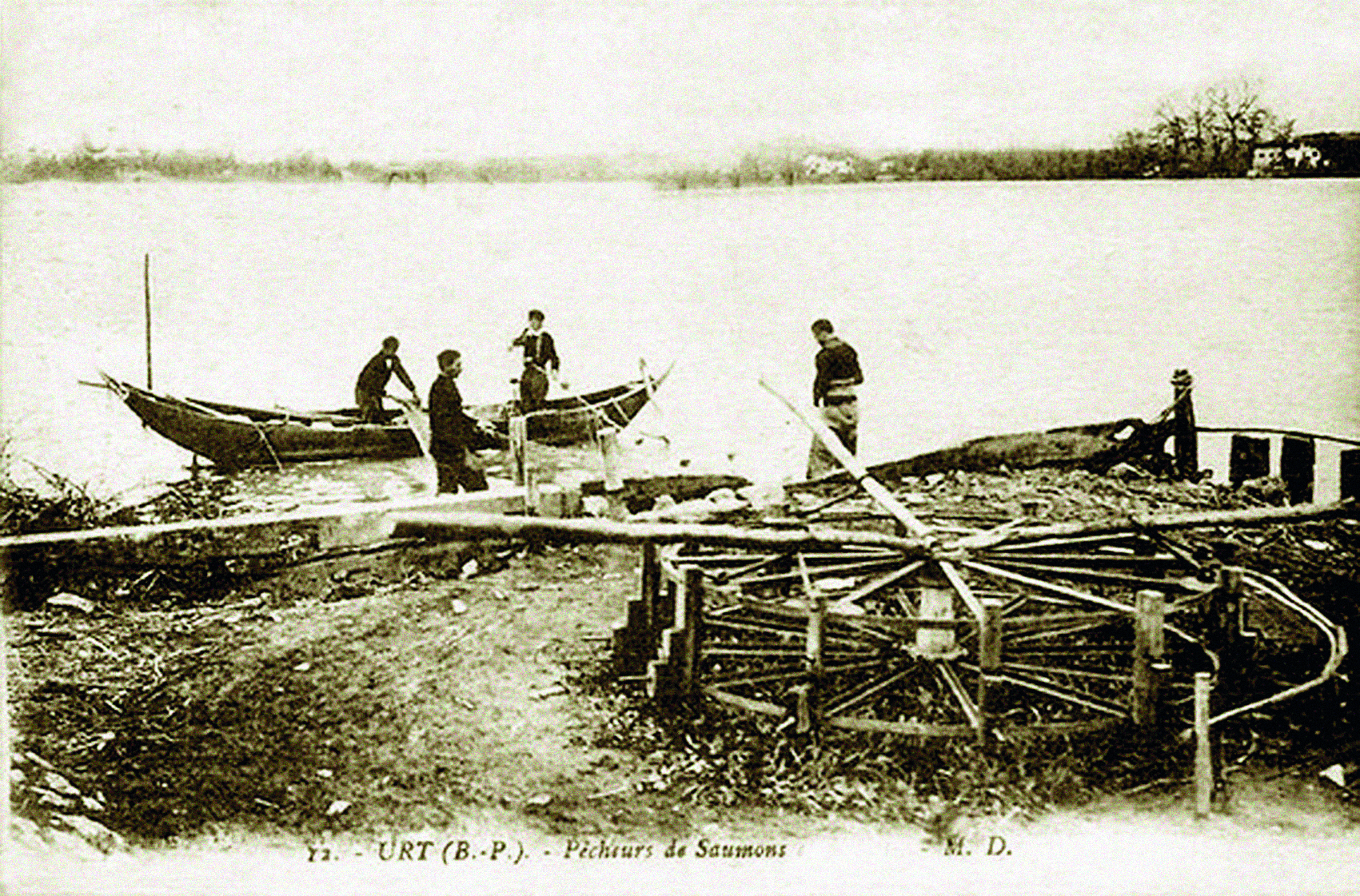

The fishing model linked to the Andenes disappeared in the nineteenth century due to the importance of defending private property and market freedom in the construction of the liberal state. Fishing was first liberalised in the Northern Basque Country, following the French Revolution. From the beginning of the 19th century, the inventions of Aturrin and Errobin baro became fashionable, with the help of numerous private investors. These mechanized network systems allowed for constant and autonomous fishing, but very aggressive for river salmon populations. Exacerbated by the risks of overfishing, its use was suspended in 1926.

In the Bidasoa it was also a time of change in the 19th century. Zuberoa's platform was lost by the dissolution of the monastery of the same name after the French Revolution. Shortly thereafter, in 1856, Spain and France signed the Bayona Treaty, according to which the border between the two states was fixed at half the Bidasoa. Hondarribia ' s ownership of the whole of the estuary disappeared, but it had no choice but to dismantle the Elorregi platform, although the French Government paid heavy compensation. The remains of the structure can still be seen on low water, under the bridge of the Biriatou motorway.

.jpg)

In addition, in 1859 a new regulation was adopted that recognizes the neighbours of Hondarribia, Irún, Urruña, Biriatou and Hendaia the freedom to fish for salmon and to sell and buy on both sides of the border. Census of residents authorized to catch salmon began in each locality, annually reviewing the number of nets in each locality. A limited timetable was approved, and each year the draw was carried out to the first round of fishing: the puppies or the Gipuzkoans. However, once the monopolies had disappeared, it was necessary to adopt measures to guarantee the conservation of the species. The documentation at the time highlights this concern, inter alia, with regard to the minimum measures for authorised fish and the limitation of potentially harmful instruments. The mesh, for example, was banned in 1897, as it caused the capture of too young salmon, while the jacket was placed in the mouth of the ria in 1927. As for cane fishing, only three specimens could be caught per person, banning longlines.

The Urumea valley underwent significant changes throughout the twentieth century. Changes, both by fishing methods and by the decline in the population of the area. According to an article in Munibe magazine from 1950, in 1900 the Urumea River was known for its fishermen and for its tourism. Before the Civil War, between 1933-36, many salmon were still being fished in the Urumea. It has been documented that some 2,000 kilos of salmon were caught a year, with a catch of 200 specimens a year and 300 in the best years. On 14 March 1939, the Ministry of Agriculture issued an order stating the prohibition of fishing salmon with nets in the rivers throughout Gipuzkoa, with the exception of the Bidasoa, in which an international treaty was in force. From there, therefore, it would be necessary to fish with cane.

.jpg)

LAWS AND STANDARDS BASED ON KNOWLEDGE As can

be read from many documents, salmon fishing has played an important role in the economy of many citizens and families and, therefore, in their survival. There are documents indicating that this trade is the only way of life for a family. In 1879 in San Sebastian: “This industry was the only support of their families,” or in 1880 also in San Sebastian: “Salmon fishing is the only activity that provides resources for life to many families, and in particular ferrons.”

These incomes, however, not only remained at the domestic level, but, as we have seen, the municipalities also granted embargoes and authorizations for salmon fishing for various municipalities were a source of income. All this has given rise to conflicts and conflicts for the interest that was aroused. To avoid this, local authorities established laws and standards. However, its development focuses on deep knowledge of the life cycle and salmon biology. That is, those who set the rules knew what the biology of fish was, and if they made the laws without taking it into account, they immediately complained to the fishermen. One thing was clear: the disappearance of salmon was to the detriment of all. In other words, fishing had to be sustainable, because in the future there was a need for salmon to exist.

Those who put the rules on the river knew what the biology of fish was, and if they did the laws without taking it into account, they immediately complained to the fishermen. One thing was clear: the disappearance of salmon was counterproductive for everyone.

Some examples of this knowledge can be found in oral and written sources. The fishermen complained that in Santa Catalina you could not fish, for example: “Salmon usually begins to climb the river towards March. From this month to June, large salmon will rise and from the latter until small August. The pups that emerge in the river will always go up until March of the following year…”. And in 1905 the fishermen complained that “the dams that have been created in the Urumea River do not meet the conditions that are based on the rules, so that the salmon cannot climb down the root to the areas where the eggs are laid, and so they return to the sea and go to the other banks. Thus, day by day salmon is disappearing from the Urumea and with it wealth”.

The fisherman Joxe Oiarbide Ttanttua, interviewed for the Burbunak and etsayak project by Hernani, also explained the knowledge that people engaged in salmon fishing have and, what is more curious, how they managed it: “[Salmon] two years ago here [at the root]. In the area called Nazabal, where the Ereñotzu Canal was located, we took the salmon pups that went down the river and with the scissor we would cut the small tail tip and they would go back to the river… and they appeared in the fourth year (around the sea, to lay the eggs in the rail). In the fourth year one of them appeared again. There appeared two and a half kilos, three kilos.” In other words, the salmon returned to the same river they were born in and occasionally caught salmon marked with scissors.

SALMON: WHEN

HERITAGE TAKES THE FORM OF FISH From the caves of Ekain to the old medieval manuscripts, to the official roles of the current Provincial Council and the Basque Government, salmon has always had its corner, its name on the table of Basque society. It is no less important, because the importance of this fish in our society, as we have seen, has left its mark.

Today, the fighting and anger among the citizens have ended. The conflicts arising from the prohibition of fishing, the pollution of rivers, the influence of the works initiated during the breeding season of salmon or the dams of hydroelectric plants on their migration, among others, are others.

The situation of salmon in the Basque Country is fluctuating, as its population must be managed according to the characteristics and problems of the river. Thus, administrations have developed salmon recovery plans. As can be seen from the old documents, pups are released each year to help repopulate salmon, and in recent years results have also been achieved in some basins with the recovery of the quality of river waters. There is, for example, the Urumea, which in the 1970s barely contained salmon, and which currently receives more than a hundred each year; or the Oria River, which still has a long road to improvement, has seen salmon again in recent years. However, there are still rivers that need to improve the quality of the water or that, once achieved, now have to work in the hydromorphology and hydrodynamics of the regatta and take into account the fish habitat to start the recovery work. Work to be carried out includes e.g. facilitating the migration of salmon upstream to find new outbreaks of laying and downstream not targeting hydroelectric turbines.

Salmon conservation is not a small challenge. At the limit of their distribution area, experts say that climate change can condition the future of salmon populations in the rivers of the Basque Country. From prehistory to the present day, salmon has had to cope with the obstacles that man has placed on it and has, to a large extent, managed to make progress against the current. Doing the same way in the future depends to a large extent on us.

When we talk about salmon, therefore, we are not only talking about a fish that can be found in some rivers of the Basque Country and that is catalogued as “of special interest”. The path he has taken and the footprints he has left in Basque society are important in managing salmon, so that he also has to take care of it for its historical importance. Salmon, because it's also a fish-shaped heritage.

.jpg)

Izokin atlantikoa (Salmo salar) salmonidoen familiako arraina da. Anadromoa da, alegia, itsasoan egiten du bere biziaren zati handi bat, eta ugaltzeko ibaian gora egiten du. Izokina, beraz, ur gaziaren eta gezaren artean mugituko da. Errioan jaioko da, eta bertan igaroko ditu bere bizitzako lehen hilabeteak. Euskal Herrian, izokinek urte bat eta bi urteren artean egiten dute ibaian, eta gutxienez 12-13 cm-ko luzera dutenean, itsasora migratzen dute, udaberri inguruan. Izokinek apirilean eta maiatzean izaten diren euriteek sorturiko ibaien hazierak baliatzen dituzte uretan behera egiteko. Hala, euren bizi-zikloaren une garrantzitsu batera igaroko dira: ur gezatik gazira pasatzeko momentua iristen da, eta horretarako, aldaketa ikusgarriak jasaten ditu, bai gorputzaren forman, baita jarreran ere. Nabarmenena dudarik gabe, osmosia erregulatzeko duen sistemarena da, kanpo-inguruneko eta gorputzeko gatzaren maila orekatzen duena. Horrez gain, gorputzean ere aldaketak izaten dira, luzatu egiten dira, eta zilar kolorea hartzen dute, urdin arrasto batzuekin. Jarrerari dagokiolarik ere ezberdintasunak antzeman daitezke, bakarrik eta leku nahiko jakinetan bizi diren animalia oldarkorrak izatetik, taldean ibiltzera pasatzen dira.

Ibaitik itsasorako bidaia horretan, izokin gazteak, edo izokikumeak (dokumentu askotan agertzen den moduan) taldean jaisten dira bokaleraino. Bidaia horretan, jaio diren ibaiaren ezaugarriak “memorizatzen” dituzte. Izan ere,

Itsasotik bueltan, ugaltzera datozenean, haiek jaiotako ibaira bueltatuko dira izokinak

Bokalean aldaketa epe bat igaro ostean, itsasora joaten dira izokinak, eta bertan bidaia luze bati hasiera emango diote. Feroe irlak, Labrador, Islandia eta Groenlandia ingurura joango dira, haien jaiolekutik 5.000 kilometro baino gehiagora. Talde txikietan pilatuta, krill-a jango dute bertan, eta pixkanaka tamainaz handitzen hasiko dira, berriz ere, ugal-garaia iristean, jaiotako ibaira bueltatzeko, ingelesez “homing” edo “etxeratzea” izeneko bidaian. Itsasoan igaro duten urte kopuruaren arabera aldatuko zaie pisua. Arruntenak 2-3 urtekoak izan ohi dira gure ibaietan, eta 2-4 kg artekoak.

Bueltakoan, izokinak kostaldean izango dira, eta ibaiek haien bokaletatik botatzen duten urari esker, jaiolekua dagoen errioa identifikatuko du. Euskal Herrian, Lapurdi, Nafarroa iparraldea, Gipuzkoa eta Bizkaiko ibaiak dira izokinak jaso izan dituztenak, nahiz eta haien artean alde nabariak dauden batetik bestera. Batzuk izokin ibai ezagunak eta garrantzitsuak izan diren moduan, badira ere izokinarentzat horren erakargarriak izan ez direnak ere.

Behin ibaia identifikatuta, izokina bokalean egongo da epe batean, berriz ere ur gezara ohitzeko. Garai horretatik aurrera, izokinek jateari utziko diote, nahiz eta hasieran aurre egiteko instintua mantenduko duten, arrantzaleen amuak heltzea egiten diena.

Negu amaiera inguruan hasiko dira igotzen izokinak. Handienak hasieran, ondoren, pixkanaka, txikiagoak etorriko dira. Izokinak errioan sartzen joango dira udazkena arte. Errioan gora egingo dute korrontearen, arrantzaleen eta ibaian gora igotzea zailtzen dieten presen kontra. Azaro amaieran hasi eta urtarrila erdira arte ugalketa gertatuko da.

Ugaltzeko, sakonera gutxiko leku legartsuak behar dituzte izokinek, eta ugal-aurreko momentuak ederrak izaten dira. Emea zorrotza da arrautzak jartzeko lekua aukeratzeko garaian. Behin aukeratuta, “ohea” egingo du, arrautzak jartzeko lekua prestatuz. Orduan, bere inguruan arrak agertuko dira, eta emea estaltzeko lehia hasiko da. Ugalketa prozesu deigarria da. Arra eta emea bata bestearen ondoan jarriko dira, igeri biak. Arra, noizbehinka, emera gerturatzen da, eta gorputz osoarekin dar-dar antzeko bat egingo du, emea estimulatuz. Klimaxa lortzean, emeak arrautzak botako ditu, eta arrak horiek ernaldu. Amaitzean, emeak harriz estaliko du eremua.

Prozesu horretan, bada kuriosoa bezain garrantzitsua den gertakari bat. Oraindik ere itsasora jaitsi ez diren izokin kume batzuk estaldura momentua aprobetxatzen dute izokin handien artean sartzeko, eta arra konturatu gabe, emeak botatako arrautzen zati bat ernaltzen dute. Hala, emeak askaturiko arrautzek ez dute beti aita bera izango.

Horrela jaioko da belaunaldi berri bat, eta ugaldu diren heldu asko, oso ahul, hil egingo dira, edota asko jota, urak haien burua errioan behera eraman dezala uzten dute, itsasoraino bideratu, eta berriz jaten hasteko, baldin eta indarrik badute.

1919an jaio zen Joxe Oiarbide Ttanttua zenak ere azaldu zituen bizi izan zen ia mende beteko urteetan izokin kontuak nolakoak ziren. Ttanttotarrak arrantzale amorratuak ziren, eta izaten zituzten haserreak batzuetan Altzutarrekin. Haiek ere arrantzale sutsuak izan, eta izokin-arrantzan aritzen baitziren denak. Komeni zenean, ordea, elkarlanean ere aritzen ziren, Oiarbidek kontatu zuen moduan: “Izokina nik ikusi dudan handiena, 6 kilo eta erdikoa. Epele-Etxeberriko presaren azpian, eta han harrapatu genituen bi. Orduan altzuetarrak eta gure aitak eta denek sozio egin zuten. Bazekiten handiak zirela, eta, sareak eta jarri zituzten, eta bat harrapatu zuen gure aita difuntoak, sarea jartzen ari zela. Handiena hark harrapatu zuen.”

Berrogeiko hamarkadan, ordea, Urumea ertzean ezarritako paper fabrikak direla-eta, ibaiaren ur-kalitatea izugarri jaitsi zen, eta izokina desagertu egin zen erriotik. Laurogeiko hamarkadan, uraren kalitatea berreskuratzeko egindako lanei esker, eta izokinek presak igarotzeko egindako eskalak direla medio, izokin populazioa berreskuratzen hasi zen. Asko badira ere azken urteetan egindako aurrerakuntzak, izokin-arrantza debekatuta dago Urumea bailaran. Espeziearen kontserbazioan dago jarria begirada.