“We become losers as we advance in life”

- I remember the autobiographical book that Aritz Galarraga doesn't want to be read personally. Assuming the formula that Joe Brainard uses in his book I remember (Oroitzen dut), he has enclaved life memories in a long line, giving way to the capricious mechanism of memory. Simple phrases sometimes, more complete images in others, for literary purposes and that build a page to page character. We have talked about the literature of the self, of the homeland, of Catalonia, and of other issues that appear in the book.

Aritz Galarraga (Hondarribia, 1980) would like to spend eternity in the cemetery of Biriatou: “I don’t think it’s the worst place, although I know they’ll do whatever they want.” Not only for the rest of the day, but for dialogue, and above all for photographs, it seems to him to be a unique place, let us not say at sunset: “There far away the sun disappears in a very beautiful way.” However, once an inn, he chooses as stage the tomb of Joseph Eyheramendy, killed in the battle of Galipoli in 1915. He's happy and largely blames the book. “I didn’t have much expectations, and what I’m getting is being beautiful. I believe that the book manages to connect in one way or another with the reader’s memory, activates something and is remembered.” It has rained us, but in the hope that it will not hurt us, we have kept ourselves in a breath and we have dialogue.

This is the first book on its own, but it has devoted a lot of time to literature: behind what you do collective writers, critics, columnists -- you almost always notice the literary intention.

Yes, I try to look at things differently. In columnality – and in journalism in general – people perceive it as being closely linked to the present, and I am not interested in current affairs, at least not as able to write: it is very ephemeral, which today seems of great interest perhaps tomorrow we are not interested in anything. So, yes, I try to look a little bit up and write something that can be legible tomorrow or the past. In the end, the literary themes, which impact us, are not many. Actually, to do something more timeless is very simple: it demands to take literature as a source of very important knowledge and experience, that is, what people have written previously and, above all, what has lasted from the written to today. I think there is a very interesting material here, which can be used to speak from today.

And now, just after the age of 40, you have published – to put it another way – a book of memory. Memory exercises are performed at the end of a life cycle, when you look back and you have to count. Is it a sign that it is at that time?

Yes, I think it has too. In any case, I think you would have to write a memory book at any time, first because we don't know if we're going to be 80 to be able to write a conventional memory book. But if the book is the closing or grieving of something. The age of 40 is symbolic – half of life, according to statistics –. As Stefan Zweig said, a kind of ascension is half of life, while the second half is the descent.

I have heard that quote before.

Yeah, but I'm going to make a quote that I wanted to bring expressly for this interview, at any time, to see if you catch it [laughter]. Continuing with the thread, therefore, right now would be at that middle point, which many have called the floria of life, that is, so that the vicissitudes of the aged youth are not yet noticeable, and so that they no longer fall into the innocence of youth. Dante said [laughs]: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita. Well, that's what we're in the middle of life, if everything goes well. And there's a grief, a desire to close things. What's the balance? In this first half we'll cry and discover what we've been on that climb.

.jpg)

You started writing these memory exercises to accumulate material, and then using them in columns or I don't know where to use them. When and why did you think there could be a book here?

At first, I would point the memories in a notebook as I arrived. By then I had read Joe Brainard's book I remember. It struck me: memory was a book, yes, but nothing conventional, and his mechanics caught you in a flood and carried you. I thought it was a good formula for accumulating material for columns, with no more intentions. One day the account took a little bit of volume, I collected hundreds of memories, and I realized that the collection had traits that were attributed to literature: the composition of a character, like peripecia, and a tone. I started making a more active search for memories, looking at photos, watching movies, visiting new places… It hasn’t been a very deep search, because I wanted to let the memory do its capricious work. Finally, I wanted to round out the work using elements of literature so that the result is identified as a literary work and not as a mere collection of memories.

Will we have to include it in the literature of the self?

This is the subject that has given me a lot to think about lately. Kontxo, I've been writing, publishing things in the press for 20 years, and I'm talking quite often about myself, or putting in a character that looks like me. I, who have someone who wants to go unnoticed, who I think I have no ambition or ambition, why do I talk so much about myself? Well, I think it's what I know best, even though I know it badly, because it's me. On the other hand, I don't have any fancy, maybe if I started writing a fictional novel I would, but at least fictional science, or that for me means inventing a very strange world, no. So my fuel is what I've experienced, what I've felt, what I've been told. And I go to the self, thinking that by doing around I can reach out to more people, and that I can talk about us and what's around us. The literature of the self is related to the situation, but it is not in my interest to tell what happened to me yesterday without more. I only use it if what has happened to me has a more universal reading.

"I only use it if what has happened to me has a more universal reading"

Ana Arsuaga told me something like this in an interview: that the anecdote that may be her life is not of interest to art. Have you had that concern when writing the book, to stay in the anecdotes?

Yes. And above all, we should not be read as something personal – even if that is necessarily the case. I haven't published this book because I think my life is very special, but because, adapted to the literary code, I could have a more universal reading. Satiating my ego in other ways, but not through literature: I don't understand literature as therapy, let alone as therapy for the writer, or for the reader. I haven't written this book to overcome trauma, for which I would go to a psychologist. It's true that I've presented it as an autobiographical book. But Flaubert said… [laughing].

I would say that now comes the curse…

You've been right [laugh]. Well, now I have to throw it right. Flaubert said that the autobiographical genre is the most false of all genres, precisely because it wants to give an image of honesty. Being aware of this, and presenting the book as an autobiographical, I would like to overcome the personal reading and not stay in detail: it is not a cancellation – I am at peace with the people, at least I know myself.

As I read the book, I've distinguished two kinds of voices: simple memories, on the one hand, and the actual comments of memories, which are usually given in an ironic tone, on the other. Is there not a conservative resource in this ironic tone, as if the mere issuance of memories was not enough?

It's curious, no one asked me, but one of those who read the book before publishing it pointed out these valuable comments, saying that maybe they didn't match the spirit of the book. You caught the damn quote, but look, Julian Barnes said he was reminded of it, but the emotions associated with those memories were not. Two things have happened to me: to come only a memory, but also to feel at the moment some emotion associated with that memory – sometimes the emotions of the time and others that have arisen in the present. And that's why there are these valuable comments in the book, because sometimes I see memories with an ironic distance from the perspective of time. In any case, it has been difficult to find the measure: I did not always want to do one thing, not always another.

Can you say the feathers to realize the irony?

Yes, no doubt. And that is precisely what I have had to curb so that the book does not get too loaded in that direction. It happens to me in columns and in any human activity, both oral and written. According to the interlocutor, I need to stop so as not to be too heavy. I have often thought that humor, and more specifically irony, is a two-mouthed knife: as a way of unlocking something complicated, it can also serve to not confront something. I try to take action. In any case, nothing is so important. To begin with, we ourselves. Anyone who takes too seriously has a big problem. And from there, everything: if there is an era of strong ideologies or very strong identities… that scenario gives me a lot of fear. The harder the defended identities are, the less the distance to freedom. It happens with national identity, sexual identity ...

"In any case, nothing is so important. To begin with, we ourselves. Those who take too seriously have a big problem."

The book rejects, among other things, hegemonic masculinity.

I think it's an unopened door that forces us to be men. In Spain there are people – Antonio J. Rodriguez, for example, or also in France, Ivan Jablonka, who are opening roads that may be of interest to others. Those of us who have a conflict with the issue should be talking about the matter.

“I remember that vasquity has become a problem,” he says at another time.

This memory is related to the need to always present oneself as a Basque in the world. Especially on the outside, you see to what extent the image people have of the Basques is stereotyped and full of clichés. So, in a moment, you might want something more neutral. To answer the question “Where are you from?” of “X” and that “X” does not generate anything, I generally prefer to provoke indifference rather than a dazzling and unfounded fascination. But then I get the feeling that the Basques are partly to blame, because we are always going, for example, up the Basque country and down the Basque country, with all those cops in the language, more concerned about how things should be said correctly than with nothing. We live our existence in a very agonistic way, as if we disappear tomorrow. Well, maybe yes -- and what? We lose too much time and energy in the shattering, and I do not know whether this agonizing attitude accentuates the possible process of disappearance. On the contrary, if we had a calmer attitude, no drama, if we lived in a more natural way, I do not guarantee anything, but maybe…

There is also a kind of fatigue with respect to the idea of the homeland.

Yes, and at one time, quite a long time ago, also fixing. Homeland is one of those ideas that you receive through your context and your education, and what you do, because there seems to be nothing else in the world, and what you don't question until you have a more mature and critical consciousness. But yes, nationalism itself is a rather dangerous issue. They say it's curated on a trip, but on the couch of your house you can also be cured with some books.

Bartleby, from Herman Melville, also appears in the book, and I think it is a good descriptor of his attitude towards life: “To choose, I prefer no.”

Yes, but then I do. I live in a big contradiction: I'm a kind of very little energy, but there's still something, an internal force, that drives me to participate. A battle arises between your supposed natural situation – lying on the couch – and your desire to belong to something. However, when it comes to participating, from far away, among other things because I am convinced that the exterior view is a privileged view and not that of the one in the middle of the whirlwind. It happens to me many times with Catalonia, people call me thinking that I can have a privileged view of the one there because I live, and I think it's just the opposite.

Look, another one that can allow the privilege of equidistance.

Equidistance has a bad reputation, especially in times of polarization. In Catalonia, the political conflict acquired a certain dimension, as it forced people to occupy a certain position. Of course, the more crude the conflict, the more and more extreme positions: the more black or white. In this panorama, he greatly appreciated the voices that were in either of the two, or those that spoke at some point in between, or directly from another. Guillem Martínez, for example, was the only one who at one point talked about the conflict, but when more people started, he kept offering a different look, because he was not united with anyone, and he was able to offer a panoramic and critical look.

"Equidistance has a bad reputation, especially in times of polarization"

It happens in many debates on the network: the clash covers the debate on concrete facts, and the calculation of position on the event becomes more important than the event itself.

Even if the sides are not well defined. Whatever the issue, we identify people with the sides. “This is on my side, that other is not.” That is very clear in the Basque literary world: there will be some outsiders who walk alone, but most writers are very well structured by groups. And you oppose something in your texts, but if someone on your side does that, then you will praise what you have criticized now because your friend has done it. The crew is a logic, in short, an institution so Basque, retrograde and antinature, that it will give you support, but you're losing a lot. The world is much larger and beautiful than your crew.

In the book, there's also a distance to groups of people.

Surely disability is more than anything else. It is not “I am special and I don’t want to have a relationship with them.” Because then I also have the need to be with people with a kind of people, that's right, that's what I'm a little selective about. But yes, the group and the stream don't attract me. What Chirbes was saying – and I promise this is the last quote – is that if most people are in one thing, I tend to go somewhere else. It's kind of a suspicion of massive things. If something likes you, I suspect you – then I can make a mistake, of course. We in the group are very manipulable and we can get to do things that we don't want to do. Great ideologies are oriented to move masses in an uncritical way to do what a few want. And, well, it surely has a lot of character.

To the extent that the book has a literary intention, it also has the construction of the character. He is not a prototypical Basque, but he has realized that he is identifiable with a very broad literary tradition: a mature man, unattached, ironic, loser… There is a very well known way.

Yes, the result of the character that can be formed throughout the book can be framed in a tradition – Thomas Bernhard comes to mind. As a reader, this tradition attracts me much more than the narratives of heroes or winners. I'm not interested in anything, because in principle I don't know if they actually have something like that. Who can see the winner in the fight against life? It is of great pretension and does not correspond to the life of the majority. Most of us become losers as we move forward in life, even physically. Eider Rodriguez has a very nice story: it is a woman who gets the tile, how before death we die the parts of the body, how we lose our hair, the physical form… The loss is an accumulation of life, more than anything else. Therefore, I find the life of those who show their wounds more inspiring than that of those who show their victories and gold medals.

"I wanted to pay tribute to my friends, especially my literary friends. I'm very lucky to have a very interesting literary environment."

You talk about a lot of people. Many anonymously, but with other names: Santi Leoné, Itxaro Borda, Patxi Larrion, Ibon Rodriguez, Gorka Bereziartua, Beñat Sarasola… Why that distinction?

I wanted to pay tribute to my friends, especially my literary friends. I'm very lucky to have a very interesting literary environment, and I can comment on my writings, the reads, the writings, etc. We talk every day, and that, except for those at home, doesn't happen to me with anyone else. From the moment you choose literature as a way of life - not of life - that is, when you choose it, not from literature, but to live in literature, because the friends of that world are very valuable, and the book is also a recognition to them.

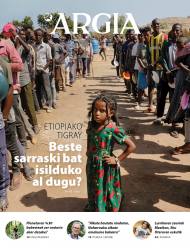

Ihes plana

Agustín Ferrer Casas

Itzulpena: Miel A. Elustondo

Harriet, 2024

---------------------------------------------------------

1936ko azaroaren 16an Kondor legioko hegazkinek Madrilgo zenbait museori egin zieten eraso. Eta horixe bera da liburu honetara... [+]

Joan den urte hondarrean atera da L'affaire Ange Soleil, le dépeceur d'Aubervilliers (Ange Soleil afera, Aubervilliers-ko puskatzailea) eleberria, Christelle Lozère-k idatzia. Lozère da artearen historiako irakasle bakarra Antilletako... [+]

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

Etxe bat norberarena

Yolanda Arrieta

Alberdania, 2024

Gogotsu heldu diot irakurketari. Yolanda Arrietaren obra aski ezaguna zait eta iragan maiatzean argitaratu zuen proposamen honetan murgiltzeko tartea izan dut,... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]

SCk Zerocalcareri egindako galdera sorta eta honen erantzunak, jarraian.

Euskal Herriko literatura gaztearen eta idazle hauen topagune bilakatu nahi den proiektu berriaren inguruan hitz egingo dugu gaur.

Rosvita. Teatro-lanak

Enara San Juan Manso

UEU / EHU, 2024

Enara San Juanek UEUrekin latinetik euskarara ekarri ditu X. mendeko moja alemana zen Rosvitaren teatro-lanak. Gandersheimeko abadian bizi zen idazlea zen... [+]

Idazketa labana bat da

Annie Ernaux

Itzulpena: Leire Lakasta

Katakrak, 2024

Decisive seconds

Manu López Gaseni

Beste, 2024

--------------------------------------------------

You start reading this short novel and you feel trapped, and in that it has to do with the intense and fast pace set by the writer. In the first ten pages we will find out... [+]

Istorioetan murgildu eta munduak eraikitzea gustuko du Iosune de Goñi García argazkilari, idazle eta itzultzaileak (Burlata, Nafarroa, 1993). Zaurietatik, gorputzetik eta minetik sortzen du askotan. Desgaitua eta gaixo kronikoa da, eta artea erabiltzen du... [+]

When the dragon swallowed the

sun Aksinja Kermauner

Alberdania, 2024

-------------------------------------------------------

Dozens of books have been written by Slovenian writer Aksinja Kermauner. This is the first published in Basque, translated by Patxi Zubizarreta... [+]