The memory of a democratic struggle to understand current cities

- At the beginning of the so-called transition, many popular movements and groups that have acted as active agents in the configuration of our cities were based on neighborhood associations. Recovering the memory of this democratic struggle is fundamental to trying to understand the cities we live today. We have talked to attorney Karlos Trenor, many popular movements and founder of the Eguia-Atocha Cultural Recreational Center Association. In this Donostia neighborhood, Villa Salia was occupied in July 1976.

In order to understand current cities and the struggles that take place in them, it is necessary to remember where we came from. Memory elaboration. The struggles of the neighborhoods, the associations of neighbors and the contributions of the citizens at the local level transformed our cities and towns, and continue to mark to a large extent the current Basque Country. With the help of Karlos Trenor, the Asociación Centro Cultural Recreativo Eguia-Atocha de San Sebastián, we have received a brief memory of this democratic struggle.

Trenor has reminded us of the weather he had in the last years of Franco in the so-called Transition: “In the 1960s and 1970s there was a special political environment. Repression of political and trade union organizations was violent.” It reminds us of the fear of the people who lived through the 1936 War, of the shooting. But, under the influence of the new generations of young people and international emancipatory movements, “in the workplace the organization and struggles of the workers were broken, and in the towns and neighborhoods we live the beginnings of the assembly movements, which eventually acquired great strength”.

At that time, Trenor says that the living conditions of the neighborhoods were precarious: “There were hardly any equipment: there were no schools, no health services, no sports facilities. The neighborhoods emerged in the anarchic urbanism, driven by unscrupulous builders, seeking an easy short-term benefit, with the support of the administration”. For this reason, the lawyer has emphasized that the first demands of the neighborhood associations were closely linked to urbanism.

In 1964, the Law on Associations, known as the Fraga Law, was passed, which legalized cultural and neighborhood associations for the first time in Franco. The associations had to draft formal statutes in order to achieve legalization, but Trenor stressed that in practice they functioned in an assembly way. An example of this is the Asociación Centro Cultural Recreativo Eguia-Atocha, created in the Donostiarra neighborhood of Egia: “We worked horizontally, I could participate and decide who I wanted,” he says.

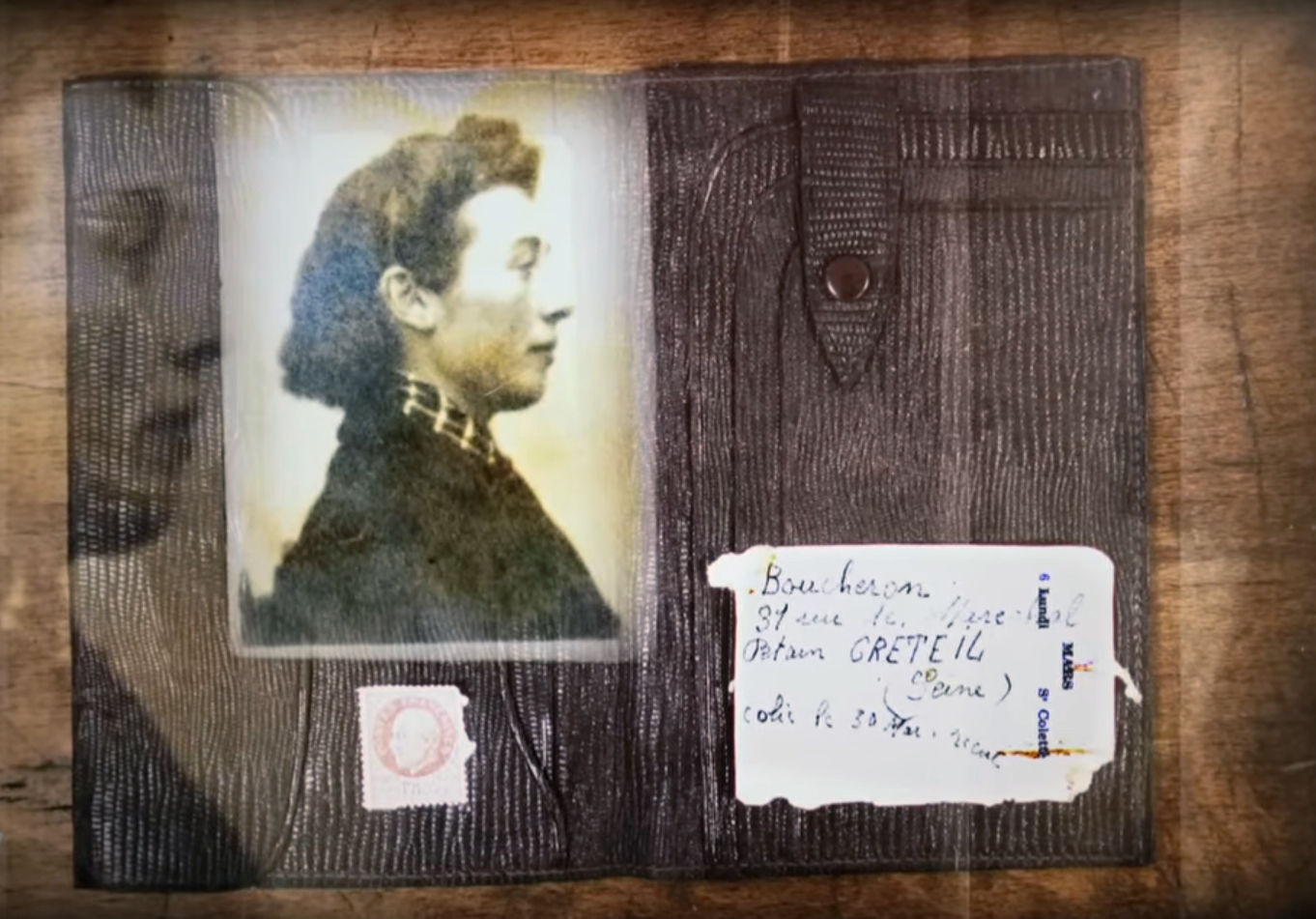

Basically, these neighborhood associations were looking for improvements in the neighborhood's living conditions. That was the main goal. “We were striving for urban improvement, traffic issues, housing, health services, cultural and sports equipment...”, Trenor said. The struggle in defense of the house Villa Salia de Egia must be framed in this context (see picture).

Both during Franco and at the beginning of the Transition, political parties were not yet legalized. Consequently, there was no room for political debate, and neighbourhood associations became, to a large extent, places for this.

However, in the neighborhood assemblies there were also debates that went beyond the concrete problems of the neighborhoods. Both during Franco and at the beginning of the Transition, political parties were not yet legalized. Consequently, there was no room for political debate, and neighbourhood associations became, to a large extent, places for it. For example, Trenor remembers that they were acting around amnesty. But not only in the dialogue, but also in the struggles, beyond the local level, not limited to the concrete problems of the neighborhoods. The fight against repression, internationalist solidarity or nuclear energy also took place in neighbourhood associations. “There was a lot of activism, and the participation of young people was massive, in demonstrations, assemblies and making banners or propaganda,” the true asserts.

Although there was a contempt for neighborhood associations for their inter-class or inter-class character, they did not focus on the anti-system axis, i.e., the conflict between capital and labor. However, “it was proved that these struggles were able to complement each other and feed each other. For example, the neighborhoods were solidary with the struggles of the workers’ movement, developing mobilizations, boxes of resistance...”. Proof of this is the strong response from the neighbourhood associations of San Sebastian to the events of 3 March.

Legacy to this day

All of these neighborhood associations and struggles have left a profound imprint. Its political influence stands out: it was a space of politicization and awareness, a space of training in basic militancy, a space for the development of Basque identity and the consciousness and pride of class. As if that were not enough, they also served to test new forms of organization and struggle. In short, fighting in the neighborhoods, tending the political systems towards democratization, projecting the inhabitants of the neighborhoods as “citizens” with rights, extending the political rights. Neighborhood associations were an organizational reflection of this, as they became an instrument to boost the political participation of the social sectors – of the staff, etc. – that the system left out.

Also from the urban point of view, important inherited transformations occurred. Thanks to them, the neighborhoods have reached a generally acceptable level of amenities, as Trenor reminded us: ikastolas, sports clubs, cultural houses or associations of neighbors.

Today it is clear that the social reality, and especially the neighborhoods, has changed a lot, the facilities have nothing to do with those of the Transition. But the lawyer is clear that new challenges have emerged: “The housing, the gentrification, the situation of adults... Future generations will have to respond to these problems and invent other forms of organization and struggle.”

.jpg)

Villa Salia izeneko etxea Donostiako Egia auzoan dago. Gizarte Aurreikuspeneko Institutu Nazionalarena (INP) zen eta medikamentu biltegi moduan funtzionatu izan zuen, baina 70eko hamarkada erdialdean abandonaturik zegoen, eta botika iraungiz beteta. Auzoan beharrezko jarduerak aurrera eramateko tokirik ez zegoenez, begiz jo zuten auzokideek etxe hura. 1976ko uztailean, antolatu eta etxea okupatu zuten. Poliziak okupatzaileak kanporatu eta etxea hesiz ixtea lortu zuen.

Urte bete pasata, 1977ko uztailean, INPk etxea saldu behar zuenaren zurrumurrua zabaldu zen. Egoera horren aurrean, berehala elkartu ziren batzarrean auzotarrak eta salmenta hori saihesteko antolatzen hasi. Lehen pausu gisa, batzorde bat osatu eta Donostiako Udalarekin zein INPrekin hitz egitera joan ziren. Udalari eskaera luzatu zioten etxea erosi eta auzoaren esku jar zezan.

.jpg)

Udalaren partetik mugitzeko intentziorik ikusten ez zutenez, uztailaren 14tik aurrera auzoan ekintzak gogortzen joan ziren: batzarra eta manifestazioa egin zituzten egun horretan bertan; 15ean, kontzentrazioa INPren eraikinean, enkantea gerarazi zezaten exijitzeko; 16an, kontzentrazioa gobernu zibilaren aurrean; 19an, batzarra frantziskotarren komentuan. Eta beste batzar bat 22an. Hala ere, INPk partikular bati saldu zion etxea. Egiatarrak sutan zeuden.

Uztailaren 24an, 500 bat lagun udaletxe parean agertu ziren, etxearen salmenta atzera bota zedila eskatzeko eta udalak eros zezala exijitzeko. 26an, bigarren manifestazio bat egin zuten udaletxeraino. Orduan ere 500 bat lagun abiatu ziren Egiatik, baina beste auzoetako jende asko elkartu zitzaien bidean. Hedabideetara ere iritsi zen gaia, hiri guztian bolo-bolo hedatuz. Manifestariek indarka udaletxera sartzea lortu eta udalbatzaren aretoa okupatu zuten.

Biharamunean, INPk enkantea bertan behera utzi zuela zabaldu zuten hedabideek. Auzoko jendea fidatu ez, eta berriz ere udalbatza aretoa okupatzea lortu zuten. Hantxe, beste erremediorik ez zuela, jarduneko alkate gisa ari zen Florencio Muñoz Múgicak –Fernando Otazu kanpoan baitzen–, etxea erosi eta auzoari uzteko konpromisoa sinatu zuen. Eta bete zuen hitzemandakoa: Villa Saliako etxea auzotarren esku utzi zuen udalak.

Orduz geroztik, Villa Saliako etxeak Egiako unean uneko arazo eta premiei erantzuteko espazio gisa funtzionatu du. Bertan izan dira, besteak beste, haurtzaindegia, euskaltegia edo Helduen Hezkuntza Iraunkorreko Ikastetxea, auzoko beharren zerbitzura.

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1930. The U.S. Congress passed the Tariff Act. It is also known as the Smoot-Hawley Act because it was promoted by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley.

The law raised import tax limits for about 900 products by 40% to 60% in order to... [+]

During the renovation of a sports field in the Simmering district of Vienna, a mass grave with 150 bodies was discovered in October 2024. They conclude that they were Roman legionnaires and A.D. They died around 100 years ago. Or rather, they were killed.

The bodies were buried... [+]

My mother always says: “I never understood why World War I happened. It doesn't make any sense to him. He does not understand why the old European powers were involved in such barbarism and does not get into his head how they were persuaded to kill these young men from Europe,... [+]

Until now we have believed that those in charge of copying books during the Middle Ages and before the printing press was opened were men, specifically monks of monasteries.

But a group of researchers from the University of Bergen, Norway, concludes that women also worked as... [+]

Florentzia, 1886. Carlo Collodi Le avventure de Pinocchio eleberri ezagunaren egileak zera idatzi zuen pizzari buruz: “Labean txigortutako ogi orea, gainean eskura dagoen edozer gauzaz egindako saltsa duena”. Pizza hark “zikinkeria konplexu tankera” zuela... [+]

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]

Linear A is a Minoan script used 4,800-4,500 years ago. Recently, in the famous Knossos Palace in Crete, a special ivory object has been discovered, which was probably used as a ceremonial scepter. The object has two inscriptions; one on the handle is shorter and, like most of... [+]

Londres, 1944. Dorothy izeneko emakume bati argazkiak atera zizkioten Waterloo zubian soldatze lanak egiten ari zela. Dorothyri buruz izena beste daturik ez daukagu, baina duela hamar urte arte hori ere ez genekien. Argazki sorta 2015ean topatu zuen Christine Wall... [+]