Ría de Agustín Ibarrola

- Agustín Ibarrola (Basauri, 1930) painted the landscapes of the Bilbao estuary at the end of the last century, before deindustrialization. The museums are located in the place where the first shipyards were, the riverside walks in the dykes place. The Bilbao estuary may not be so gray on the surface, but the landscape is not only superficial. In the exhibition installed in the Maritime Museum you can see the paintings ambitioned by Ibarrola in the estuary.

The Sun continues to play tirelessly today. It is enough to leave the shadow so that the suffocating heat protrudes from the wind that refreshes at least a bit of the Bilbao estuary. For those of us who have not known it is difficult to imagine what the landscape of the Euskalduna area was like at the time of the shipyard. How the laugh has changed so much. Only remains. A museum that picks up the history of the shipyard and the rías, a hall of acts with the name of the shipyard, a single crane, embalmed with red paintings that renew from time to time. The Carola Red Crane is just a monument reminiscent of the industrial heritage of a not-so-distant past. We go down to the pier and the traineras of colors just taken out of the water, about to enter the water, people ready to paddle, it seems like it's the race day. On the dry pier some containers, anchors and chains on the sidewalk, to adorn. The Itsasmuseum, Bilbao Maritime Museum, is located in the location of the shipyard dikes.

It seems there are few people inside, it's Saturday afternoon and there's a good time. The woman at the entrance explains that to visit the museum you have to follow a path, which is nothing but following the marks of the soil, that you have to bring the kiss at all times, that there are enough bottles of alcohol to wash your hands. The exhibition of Agustín Ibarrola? At the end of the ground floor, to the left.

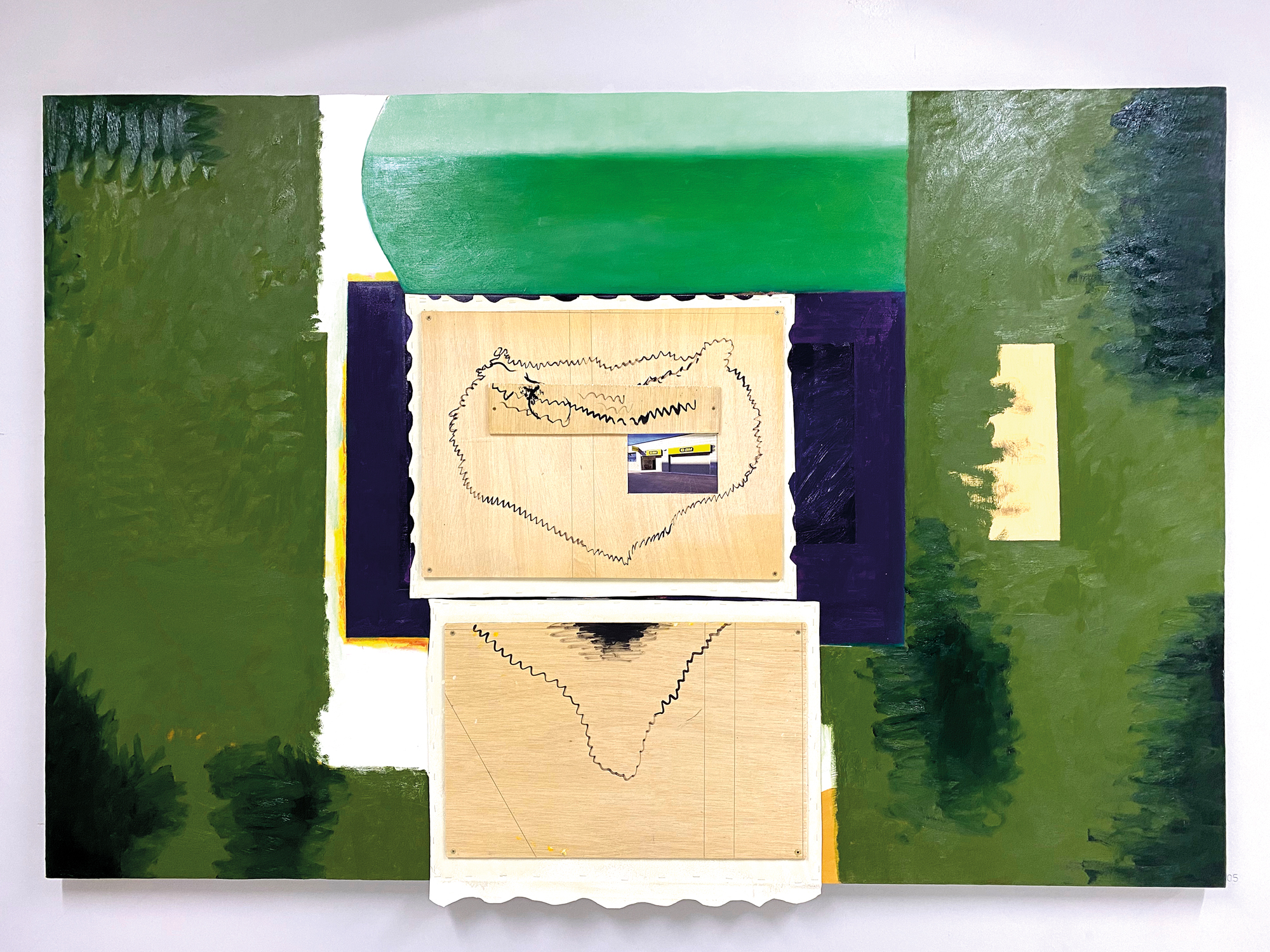

Agustin's son, Irrintzi Ibarrola, has been in charge of curating the exhibition they have made in collaboration with Laboral Kutxa. Seventeen paintings of large oil, twenty drawings and a small sculpture that capture the estuary of Ibarrola. The museum seems a good place for this exhibition. Painting of the surroundings and time of the shipyard on the yard grounds. As the subtitle of the exhibition says, “water, fire, iron and air” appears. These works recover a landscape that no longer exists. There are few texts in the exhibition, and it is useless to look alongside the works for some distresses that mark dates, titles, etc. They say that these works are dated and not named by the artist’s decision, “you know what artists are like” tells me the women at the entrance. The title, two quotations, and part of a catalog, maybe next to the drawings, just some hand-made note by Ibarrola. The viewer faces the images on days like the current one and thanks for the calm and the freshness. This is a simple exhibition, in which many of the canvases lack wooden frames. The colors of a distant landscape occupy the space, too small and large, too dark and bright, colorful and gray, figurative and abstract, the contradiction predominates. The echoes of water, fire, iron and air come from the canvases. A similarity to the outside landscape, like the red trainee in the air in the blue waters.

Colour and geometry

According to the exhibition catalogue, Juan Ángel Vela del Campo, the exhibition of the Maritime Museum is not only an exercise in recovering the aesthetic memory of the past. He claims the humanistic and social roots of a creator committed to the time when Ibarrola has lived. In a way, these works occupy an intermediate space in the chronology of the known works of Ibarrola. No colourings or pure figurative pieces have been engraved at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao, also of a grey colour. Nor are the colorful interventions he has made in nature in recent years. But there are the figurative forms, framed by geometry, and also colors. The colours of the estuary are combined with those of the “working world”. According to Ibarrola: “The world of work has form and color, it is a world that has shaped my sensitivity. I have reflected on aesthetics throughout my life through the forms, structures and relationships generated by work.”

Among the large canvases, three types of islands are distinguished. A small bronze sculpture that shows a single silhouette, a table filled with varied drawings and a cell with more drawings. These drawings, the sketches, are important to Ibarrola, as they keep a first raw impression. They are these research materials, the first raw approximations, but they help explain the evolution of the artist's work.

Given Ibarrola’s long journey, it is difficult to take this into account. From a very young, intuitively, he didn't want to go to school and instead he filled the notebook with drawings, took a great record, took him to the dwelling and made a sculpture with him. He studied his first studies at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bilbao and after his first exhibition, while still young, he moved to Madrid to study as an assistant in the study of painter Daniel Vázquez Díaz, with a scholarship from the Provincial Council of Bizkaia and the City Council of Bilbao. From there, its trajectory begins to expand and become more complicated. He returned to Euskal Herria and maintained a relationship with Jorge Oteiza. Subsequently, Paris was exiled and, above all, the team Equipo 57 turned from the second half of the 50's. Equipo 57 delved into the theories of the currents of the avant-garde of the early twentieth century, especially on the road of constructivism, where Ibarrola found a theoretical basis, a direction for his artistic activity.

The landscape is also done by people, and Ibarrola not only teaches these people, but wants to question them.

The exposition is broadened with Ibarrola’s words on the social function of the work:

“The work of art that identifies the artist’s dialogue with the reality of his time is more than translating that reality, it helps to sort it out. It expands and enriches the understanding of this reality and gives us greater capacity to influence it. The influence of the artistic work on social life makes us more aware of the facts around us, cultivate sensitivity and thought and strengthen moral principles.”

It says Ibarrola

Ibarrola de Aresti and is thought of in two images. Intervention on Mount Oma (Kortezubi, Bizkaia), on the one hand Painted Forest. On the other hand, black and white engravings. Some of these prints are easily related to the poetry of Gabriel Aresti.

Three years younger than the painter, Aresti and Ibarrola found themselves young. According to Anjel Zelaieta in the poet's biography, Gabriel arrived at the cafeteria La Concordia at the hand of his older brother, where writers and artists met. Besides Ibarrola, Zelaieta mentions Emiliano Serna, Blas de Otero, Vidal de Nicolás and Gabi del Moral. By then, he was already "Basque aware" among the "Castilian speakers".

The relationship between Ibarrola and Aresti came to fruition shortly afterwards. In 1965 Aresti won the Lizardi Award with the book Euskal Harria. He published his book in 1967, in the newly created editorial Kriseilu. At first he had 120 poems, but half were censored. Along with the poems he was engraved with Ibarrola, some of which were also censored. In addition, Ibarrola was arrested again before the book was published in a demonstration in favor of striking workers at the Strip Mill factory. The third part of the book, in Spanish, is dedicated to Ibarrola, and is one of the proper names that appears repeatedly in the works of Aresti.

The humanity of the

landscape The engravings of Ibarrola and the so-called social painting are exciting. Representations to the return of industry that show and denounce the way of life that comes with the work. The many interventions and sculptures he has made in nature are also exciting.

But this spectacularity goes beyond the work in the case of Ibarrola. He did so publicly against Franco, and from there he also suffered the repression. After the so-called Spanish transition, especially since the 1990s, the name of Ibarrola has also appeared on the political pages of the newspapers. Enough is enough! He was one of the founders of the Ermua Forum and was about to sound as a result of the statements made against ETA and Basque nationalism in general.

The works of Ibarrola have also been attacked on several occasions. For example, the sabotages that have been carried out in the Oma Forest are known. There are other attacks on the newspaper library. Its uniqueness calls attention: In 1992, several sculptures were destroyed in the streets of Vitoria-Gasteiz. The painter Santos Iñurrieta tore down a series of sculptures made by Ibarrola with wooden sleepers at the time the then councillor of culture of the city passed by the side. The event caused a scandal. Iñurrieta explained her action to protest the cultural policies of the city of Vitoria-Gasteiz. It is the public work that opens up to the landscape and its people.

Landscapes are not just images. Landscapes are made by people, and Ibarrola not only showed those people, but he wanted to question them. What can be felt between the water I wanted to transmit, the fire, the iron and the air. The landscape of the estuary has changed, but you can still feel similar things. A few meters later, the Guggenheim cleaners are now on strike with their shapes and colors.

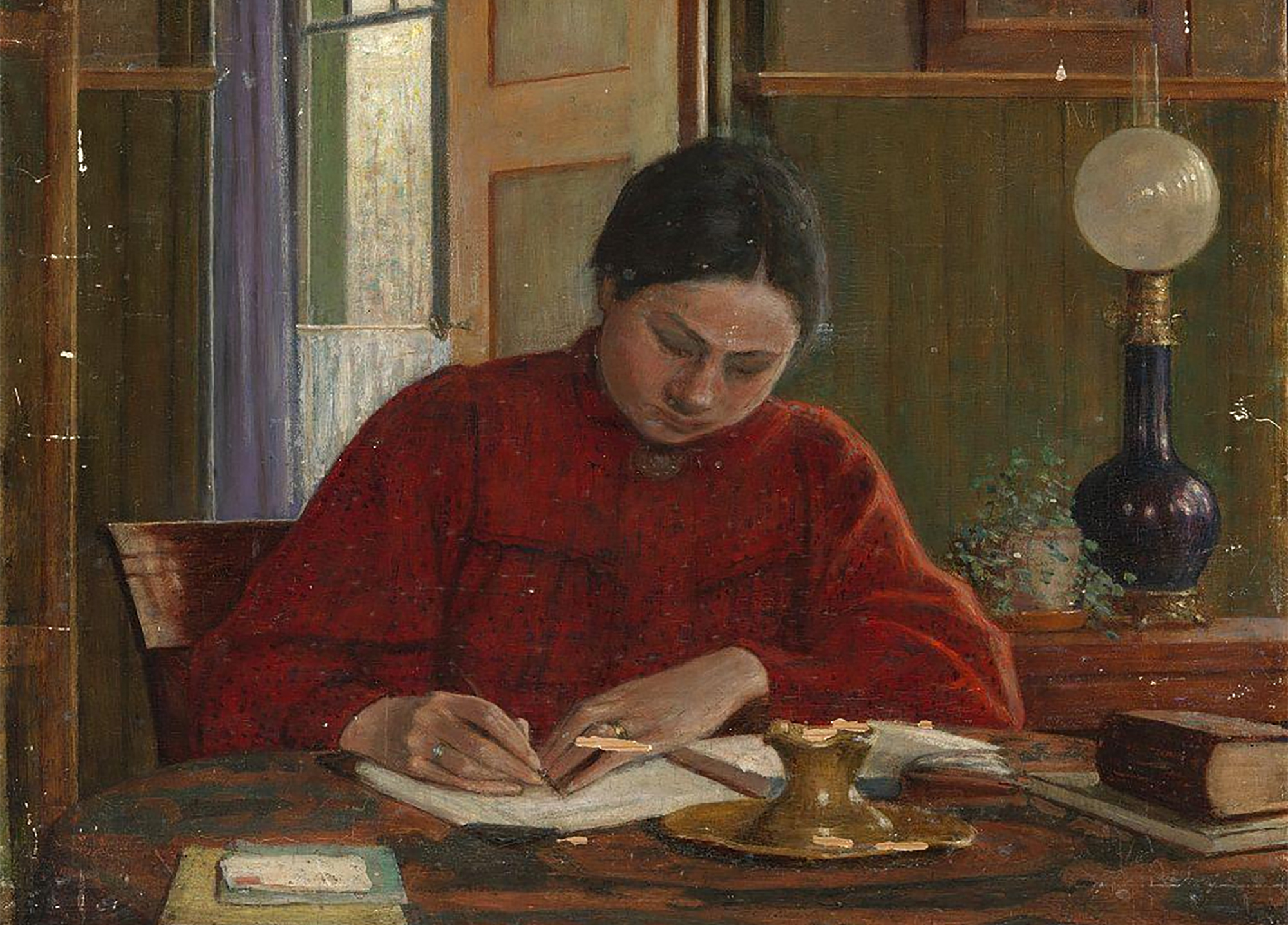

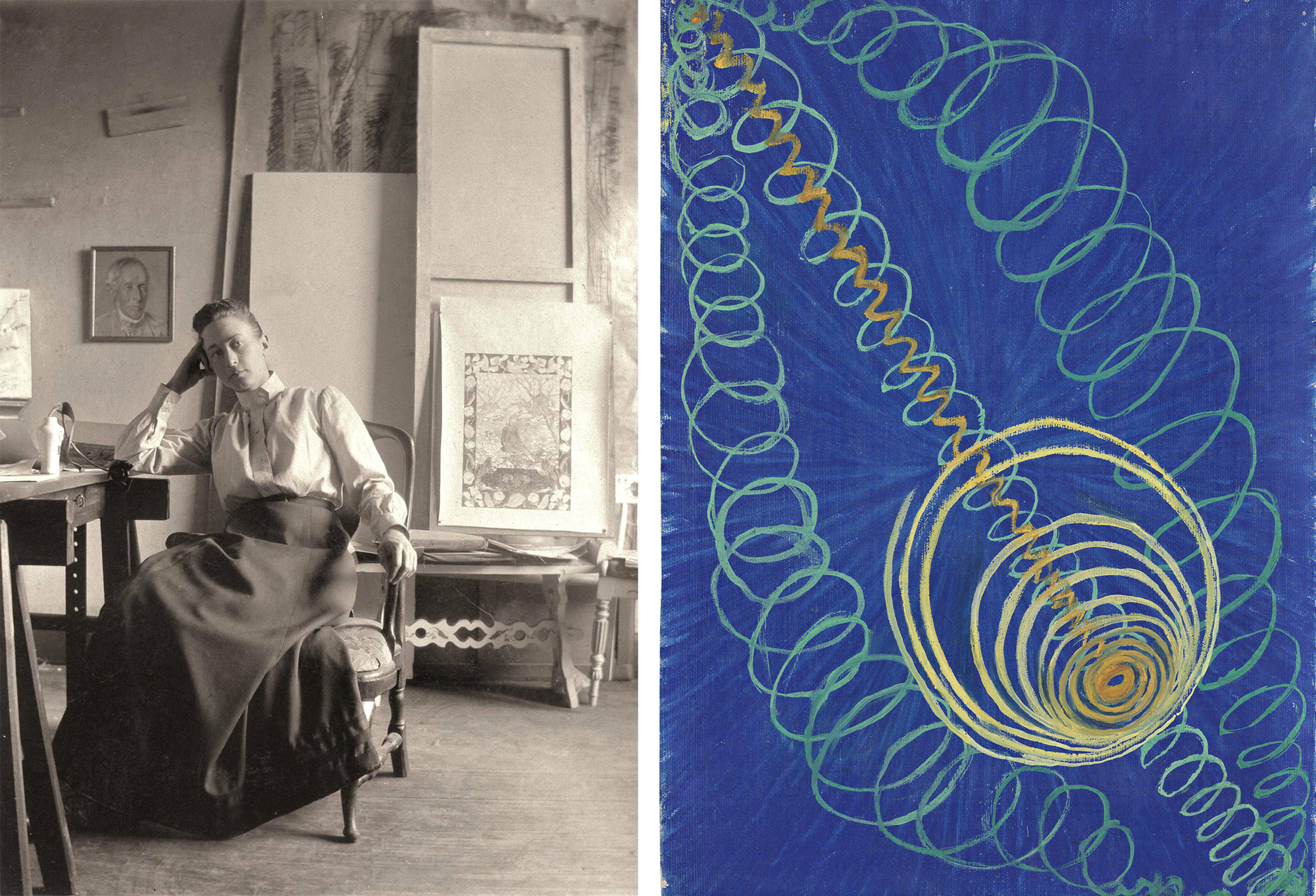

Bussum (Netherlands), 15 November 1891. Johanna Bonger (1862-1925) wrote in his journal: “For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on earth. It was a long and wonderful dream, the most beautiful one I could dream of. And then came this terrible suffering.” She wrote... [+]