"This book is not an ammo for the battle of the story"

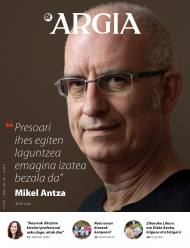

- With the work Arroz Ur (Txalaparta), published in March, we have been quoted in the Katakrak of Pamplona with Mikel Anza, not much loved by the interviews (San Sebastián, 1961). The outbreak of the Burgos Lawsuit against the leadership of ETA in 1970 with his personal biography has made a report of the last 50 years of Euskal Herria: his, “personal and introspective”. Although on several occasions we have come across themes and ideas that “cannot be spoken”, he has spoken to us long and hard about his latest work, his literature, his politics, his history (built by men), his memory and his story. The expanded version of the interview we have published in the weekly is the one that can be read below.

You've published a paper called Rice with Water. How would I define it?

It comes out as a literary essay. It has a lot of autobiography, history, research, journalism and literature. When I was writing, I realized it was something special, both structurally and fundamentally. If I tell you that I have not read that before, I may not have read you anything, but that is the case. Writing has been very organic, very much about the book. I didn't know what its shape would be and whether it wouldn't work. So far, I've been working further apart on other literary works, even with more feedback, and I knew what was going to work in a literary and comfortable way. This time it's been unknown to me, and when I had the book in my hands and read it, I realized that it worked.

The title refers to a method of getting messages out of jail clandestinely, writing things between the lines of the books from the water to cook the rice and then reading them out. Are there many things between lines in the book?

The title appeared in the center of the book and I think it indicates well what is inside it. In the writing process, there is a lot to be removed thanks to the editor. What I wrote from a bitter, acidic, vindictive tone is lowered, not from the political, but from the staff. In a couple of sentences, I would lower it a little bit more. In the latest tests before I send them to the printing press, I will take away thinking about “this phrase will not bring anything good and will hurt someone.” I didn't want to create it. However, I have not kept that I meant, that is, the book I wanted to write, in the way I wanted to. But there are many things you can't say, and yes, with rice water, between lines, there are some messages for different readers.

Burgosko Auzia is the central axis of the book, but this is not a history book. Have you had books or jobs that have served as a reference?

To my ignorance, I have to say no. I don't have another book. It originates from the comic book on the Pleito de Burgos commissioned by Adur Larrea and bioi Gara. I had to make a script, we had very little time, so I proposed adding an annex. As I wrote this, I realized that my biography was related to the Question of Burgos, that I had a relationship with the facts and protagonists of it. So I started building that annex, but it was larger than the annex, and so I pulled it apart to do another project. And to turn all of this around, I realized that in my biography was the beginning of ETA and the end of ETA, although there may be a different beginning and end. It's a very personal, introspective book on a large scale.

He says that he is very personal and that he has taken the distance later. At the same time, Mikel often speaks in third person.

I was very close to the writing process, because some things were happening to me by chance or by chance as I wrote. Meet Unai Dorronsoro, make an appointment with Arantxa Arruti, the things that happen in the chapter of Julen Kaltzada... And 3rd person writing had two reasons. A stylistic: written in the first person didn't work. I couldn't write first person, like, "I was born." Take the distance I needed...

It didn't work for you...

"Talking about myself as if it were another, when I was in prison isolation, I had such an attitude."

Yeah, yeah, me. And on the contrary, when I put myself in third person, when I talked about myself as if it were somebody else, it worked for me. Those subjected to torture, which count those who have been tortured, or when I was in prison isolation, I, for example, had such an attitude. I saw my situation and that distance allowed me to talk about myself. In the book there's third and first person, and I had to mark very clearly that moment that passes from one side to the other, although in my head it was very clear: I'm back in Euskal Herria. Here I make a little reflection: I did not return from prison, I returned from prison, also from prison.

He highlighted the work of the editor in the interview that was sometimes done in the Basque Country Irratia, Arratsalde on. What did the book fix you to the work of Garazi Arrula?

He worked a lot. I gave him a while, supposedly the book. At the time, we had the comic book in our head, and he proposed to dedicate myself to time and leave later. He said to me: “Now you have to take it off,” and I said: “In any case, I will add ...” He has done a very discreet editing work, on which I have taken off and taken off. “Mikel, this is not understood,” he said to me, and in most cases I have given him the reason.

.jpg)

Therefore, the book has been summarized quite a bit from the initial version. Has there been any reason for this, there have also been safety issues?

No. The metalworking was tremendously. Some accounts have been very summarized, and I think they are more effective. When you start writing something, you count everything, and then, when you do it for the second time, you're much more effective. In this respect, it has been summarised.

Mikel Soto says in a poem in the book When the fires are turned on, that when you give it to an attorney before you post a poem, you're not a poet. Have you done this?

I was told if I would give it to an attorney, and I was clear: no. To an attorney for what? I already have an editor, he sees it. An attorney will tell me at most “hear, I don’t know what with this.” I do not see any sense to him. If I have limited myself, I do so because I see, on the one hand, the political situation and the consequences it may have, and, on the other hand, because, above all, that book is not a place to talk about many things. It's a very personal book. I personally could say a lot more about issues that occur or happen in our country, but who am I to say? I cannot speak on behalf of a group, on behalf of a group; of myself, but of me too, to a point, because that has consequences, not legal or penal, but personal in relationships with people, in mines and in experiences. A book doesn't seem like a place for it.

“To talk about what has happened or is happening in our country, who am I?” he just said. Well, anybody can be somebody, but you're also Mikel Antza and you've been where you've been. There are a lot of people who may think that “of course there is who to talk about that”, but when we advance him that we wanted to talk about it as well, he said that he did not want to talk about ETA or the political situation. Why?

"If we were free, we would have to think differently about the consequences of this armed conflict in our country and the issues of what ETA has been, but we would have to think about them, not like today"

You can't talk in Euskal Herria, to start with, because we're not a free people. If we were free, we should put in another way the consequences of this armed conflict in our country and the issues relating to what ETA has been. But you should think about it, not leave it as it is today. Because it looks like there's a pool full of I don't know what, and we're all going around, but most of all you want to throw one back to the pool. There are the prisoners, there are the victims, now a law has been brought out, then another, our people are divided... but the issue is not addressed.

The Basque conflict and its biographies are also very present in your previous work: Abroad, in the hospital, in Dreams... Do you need to write about it?

Now speaking of literature, this is the end of a trilogy:Pessoa brought out the Sarrionandia theater, the Pleito de Burgos: the revolution and the vital comic and the Rice with Water from prison. I participate three times as a writer. The first, prior to 7 July 1985; the second, which I rewrite in prison; and the third, which he wrote below. Among them is the story book entitled The Smell of Blood, when I took refuge. I use as a resource that of self-fiction abroad and in the hospital, but in all my literature there are autofiquia, literature that starts from personal experiences, although at first it is much more disguised. So I can see my life, and I turn it into literature. When I was in jail, I got writing like this. It's a conflict-related autofition, to a point. I would not like, after the publication of this book, to be an expert in “conflict literature,” quite the opposite. I will continue to do autofiquia, but I hope not.

Can it, therefore, be the closure of a cycle?

I've written it from my very special watchtower. I see the issues in order to be able to do written works relating to the conflict, I consider them necessary, but I do not want to go into that. But I'm tempted, because I see the void and what to talk about a lot, and because there's a need.

The title of the interview he conducted with lawyer Miguel Castells in December for the Gara newspaper was: “There’s no freedom to talk about ETA.” You have done the way of talking about the issue. Are you worried about the story?

This book is not an ammo for the battle of the story. We are emerging from an armed conflict – well, one part has left it even if the other one follows it – and as this ends it seems that we have to enter the battle of the story, it seems that they lead us to it. I personally am totally against it. I think it is a mistake that we could have made. In Euskal Herria, in society, I do not see the need to match another story. Now Patria has come out and we will do Anti-Patria, now a series has come out and we will do a comic book... From us and for us I see the need to write, I have done it out there. We have to reflect internally, yes, we have to talk, but not according to what others say. In writing, the attitude will be very different if I have to build a story to question defecation based on lying and manipulation, and I have to pull out the “truth”, not because it interests us, but to confront it. This brings us back to what we want to liberate. For them we have to write, we have to do it in Spanish, etc... there is no battle of the story, or at least I have no interest in it.

You insist on the need to write from us, but that “we” is also very subjective. I don't know if you've read the book by Joxe Iriarte Bikila, or by Karlos Gorrindo, by Emilio López Adan Beltza... Do you situate them within that expanse of us?

I haven't read them. I have followed, I know they have come out, but I do not know from what point of view they are made.

Some are very critical of ETA, like Gorrindo's. Joseba Sarrionandia said in the introduction of this book, “well, this is also, and you have to talk about this.” What is there?

"Doing a first act had legal and criminal consequences; today we have to be very careful with the word"

We go back to the headline of Miguel Castells. The problem is that, once again, some of us are forced to write with rice water, between lines and invisible. Not all speeches are possible because today our country is oppressed, because the Spanish and French jurisdictions decide what is the sustainable discourse and which is not. Each one has his own experiences:The Black has his own, Bikila his own, Gorrindo his own, but if we work with a little fair play we should all be aware of what Castells says. That there is a community made up of people who have fought for the freedom of Euskal Herria and who have forbidden the word. The implementation of a first act had legal and criminal consequences; today we have to be very careful with the word. That makes me uncomfortable. That is, you can say what you mean, but I can’t say “that’s not the case” or “I see this as well”. Why? Because we're not at liberty.

In this sense, the book makes little explicit assessment of ETA's trajectory, few self-critical comments... However, the chapter of Sulatino Xanpier Etxegoihen draws our attention: In the book it has been collected that it has helped ETA and has blamed it on what ETA was doing at a given time.

I have collected it to demystify the monolithic and uncritical vision that has emerged from ETA militants. Here I put Xanpier Etxegohui to show, on the one hand, the plurality of people who have worked in the organization or militant of the organization. On the other hand, one thing is what one can think of what an organization does at a given moment, and another thing is that you in your militant or citizen power – Xanpier did not see yourself as a militant, but as a citizen – could have a hyper critical view of what an organization did at a given moment. I have been a militant of ETA and from what I have seen that is absolutely normal. With every action, with every event -- but how do you eliminate that with the pain that comes from it, with the pain that you feel and in the midst of an existing war? That's the question.

George Orwell in his work, Why I Write, listed four reasons for writing: absolute selfishness, the aesthetic goal, the historical momentum and the politics understood in the broad sense. Do you feel identified with any of these?

Why you write and why you publish are two different things. Writing can have a very bital pulsation. Writing is a way of self-understanding, of reading, of analyzing. Like putting yourself in front of a mirror, putting and seeing in paper the eddies, phrases, feelings that are in the head, when they materialize, we can say yes or no, or well, now I see it clearer. It's a very human exercise. And publishing is showing that mirror from one self to another. It becomes something that is done directly with the aim of showing the initial personal exercise. In my case, and being faithful to the literature, the things I have wanted to publish have always been thinking of the reader. I want whoever reads my book to enjoy and feel pleasure, as I feel when reading. I don't know for what purpose that is linked to in Orwell... Maybe aesthetic selfishness? [Laughter].

And literary Mikel jonki, what does he read?

I read a lot in jail. I signed up on an Excell table and read over 500 books. When I went out little, and now I'm reading a lot again, even if I don't like it. I'm finishing the small town of Ene, the town of Gaël Faye, and then I intend to read the Winter lights of Irati Elorrieta, before I read the VHS of Oier Gillan, before the Xabier Montoia Taxis never stay...

"I'm very interested in literature written by women, I think there's something special."

I'm especially interested in literature written by women and lately I'm reading a lot: The Mothers of Katixa Agirre do not have, Basa de Miren Amuriza, Dendaostekoak de Uxue Alberdi, Alaine Agirre's white nightgown, Casa del Padre de Karmele Jai, Moyo de Kattalin Miner... I was particularly interested in the manifesto of Andrezahar de Mari Luz Esteban. In the groups of readers I have dedicated myself to them and it seems to me that there is something special in the literature made by women. Perhaps not new, but different, another vision that interests me a lot and that leads me to many reflections.

Going back to the book, it draws attention to the accuracy you handle with some issues. To give you two examples, the details of the car they used to kidnap Consul Eugene Beihl or the full listings with names and surnames of the people who were tried together with their father. It is clear that he wanted to leave certain things accurately documented.

Not everything can be told, and therefore, in history we have some remains of this kind. I studied history, and I wanted to extract that data from the excavation that I've done in writing the book for many reasons. Especially to leave a mark. Subsequently, I have received an echo of some of the names that appear in it, thanking for their presence. Otherwise they disappear. I insist, it's a book about me and my environment, I've collected the names that affect me.

He has said that his father was one of ETA’s first militants, participated in the attack on the Francoist train in the 1960s and was sentenced to 20 years in prison, after several decades like you. Your mother, when you were a child, was hiding ETA’s propaganda under the ballast of her cart along the streets of San Sebastian. In those days of Franco, what was the atmosphere they had at home?

We didn't talk about politics. Upon entering our house, Castilian was left out. Only Basque was spoken in our country. He did not know to what extent the parents agreed or disagreed with the institution's incidences. Dad started militating later in the ESB, there were magazines and books in Euskera... but we talked little about politics. We knew my father was in jail, but he was good, he wasn't bad, and so on. All these things that I tell in the book I've met once inside ETA, are things that I've asked you during a visit. I know my father's because I asked him exactly how he was arrested. Orga's is important to me, because that means that I had been during the two months that my birth and my father's arrest lasted, or that my mother had been distributing propaganda after my father's arrest. I think it is important that in one chapter we reflect on the participation of women as militants.

You can see that the Pleito de Burgos left a mark on you. Did anybody expect that explosion?

I have to say that in writing that script about the Burgos Affair, in documenting it, I realized those two things. I had a relationship with me, the cassette [how Mario Onaindia relieves the lawsuit and how the defendants sang Eusko Gudariak] was brought by my father... but by documenting it about the comic I realized what the Burgos Lawsuit really was from a historical perspective. ETA was born in 1958, but until 1970, let's say, it was nothing. And then, not only did it become something, it geopolitically placed Euskal Herria on a global level. When talking to older people in the book presentation, it's clear that it was an explosion.

You also convey the emotion with what happened. Has it been created as it has been documented?

No, I don't think. I have a concern, and then I wrote as a critic a chapter that I've greatly reduced. Ten years after the first elections of the Pleito de Burgos, "we have won" in the singing mittens. I was 18-19, when the Burgos Lawsuit happened nine, and I didn't understand it. We were on the expansive wave of that explosion, of that Big Bang, but nevertheless, we didn't understand how that world came about. In the demonstrations, for example, I lived politically all that salsa, the actions, the repression -- but we didn't know where that salsa came from. What did it mean to this people? What about Spain? For France? For the world? We weren't politically conscious. The politicians at the time knew where they came from and why, but the young people didn't know. It is my concern today to know to what extent we young people come from where we come from.

"My concern is to know where we are, why we are -- what's happened?"

After Arjel's process, we talked to the young militants who were then 10 years old and didn't know what it was. But there was a struggle that gave explanations. That is my concern, the transmission – not to continue in politics, but to understand it – to know where we are, why we are, what has happened, not to value it or to applaud it, but to know what has happened. Here we come back to the previous account: as you cannot speak, you cannot convey it clearly, my concern is whether you are not silencing. "I didn't have to have happened," some say, or "I don't agree." Now -- but it happened, so let's know what happened and why. What has led us to this situation? I think that is the exercise that needs to be done. You have to understand it, you have to agree or not, that is in the background. I've tried to take him to the personal section in the book, counting my personal process. How did I get into that organization, etc.

Do you see epic as an important element in politics?

This point I put with rice water as well, it's lowered in the book. I think these are also constructed speeches. Maybe someone needs that epic. By saying “it takes a new epic,” I don’t know what it is.

Bertold Brecht has a widely used poem. "Man," he says, but good. "There are people fighting for a day, and those are good. There are people fighting for a year and they are very good. And there are people who struggle all their lives, and those are the essentials." I am totally against it. I believe that all those who fight one day are essential. One day in one, another in another and another in the next... Otherwise we cannot explain, as Castells says, how we have arrived here. Those who fight throughout their lives are very few and cannot do much with them. "What do you do? "He's left the fight, he's making kids." OK, he's fought, now he's doing something else, OK. In the field of epic, I think we have to go further. As Arantxa Arruti says, have women not been in ETA? That's not true, they've always been there. As I say in the book, which is most important, the militant who is in the meeting, or the one who has prepared the food, or the one who has left the house ... That must be turned around, we are all important and not a few.

For some here, there's very little self-criticism. Would it be easier to be more self-critical if the possibility of praising those who want to praise were free?

I have no need or desire to praise. In my view, there are realities. I have come to Pamplona and here we are talking in Basque in Katakrak. What do I have to praise for? But, well, everything is political. I'm going to talk a little bit about politics. There was a group with some goals, a group of people, a people. And they were in front, other groups of people with other goals, some states. Some wanted one thing and others. I do not have to praise anything, I see the reality. What I can't do is insist too much on what that reality looks like, because if not, someone will say I'm exalting, and I don't need it.

Self-criticism goes at once. I say again, if there were conditions to speak, if it were clarified what the objective of this self-criticism is -- it would be something else. Do you have to self-critique that tortured me? But I want to know why you tortured me. I'm sure you're a sadist, but also, why did you torture me? That's the goal, what we need to know. I know why I have fought, why he did that institution, well, badly ... Why you've fought, that's what you should explain. Why.

In the book he also talks about Martutene's escape. If we were not mistaken, for the first time he told us that he was there with details, what the day was like...

Yes? Do I tell you? What do I tell?

Well... he tells you how he came out of the house leaving your girlfriend, who had the van rented in Bilbao in the parking lot of Alderdi Eder, who you went to Martutene with two empty bafles inside, you entered, you went out with the filled bafles, the joy of the moment... and the floor that were hidden for three months in the neighborhood of Egia...

Yes, but most things had come out in the Major Water program that ETB did. If I have not wanted to talk about this leak, it is above all because most of the data was pulled out by the police as a result of a tortured fall. So I didn't want to talk about it. The actions are collective and I do not count on anything in the book. The new thing I'm telling you is how I got out of my house, I'm telling you where the van was parked because it was important for the script, but you know where I rented the other car, which I rented it for me ...

...all right, but forgive me, we didn't want to ask him that. We wanted to ask him what it feels like to help someone escape jail.

"When someone escapes from jail, we all flee."

Ah ... [Awe]. Anyone can imagine: happiness. I put it in the book, when someone escapes from jail, we all flee. I have tried to summarise the feelings that may exist around a leak, for those inside or outside, for whom it has participated. You have to ask someone who has escaped: “What did you feel when you fled?” I think it'll be like re-birth. Birth. And therefore, helping is like being a midwife. It is a very feminine action from my point of view.

And what does it feel like when you meet with the person who helped you work as a midwife after 35 years?

I once found myself in Usurbil by chance [Iñaki Pikabea] with Piti, after many years... joy. And with Joseba -- weird. After all, in the photos we have seen a lot of how we have changed. However, this issue is very intimate.

So you don't want to tell more about the leak...

It is an act claimed by ETA, like others. My name is known because it was essential to make himself known and that of another member because he was arrested. But it is a collective action, actions have no name, neither one nor the other. That is why I do not want to talk about this action. “What a nice action,” someone might think. I always remember that two days later in the Treasury delegation there was an act against two civil guards. It was also a collective action. Everything is conflict, then we are glad of some things, but the conflict is everything and I think that is important.

It talks about the leaks, it is not as well known as Martutene's, but the Operation Bottle that the members of ETA VI.eko were about to release the prisoners by tunnel under Burgos prison, he picks it up in his book. What consequences could it have?

I use it as philosophical or political reflection. Everything is history, but history has crosses that can change radically. The Pleito de Burgos was thus with all its components. But it had outputs that would completely change the story. It would be very different if, in a cassette, instead of listening to the voice of Mario Onaindia, he escaped from prison and saw himself at a press conference in Paris, giving his face to the 16 involved. The story would have been completely different if that leak had gone ahead. In the political analysis, this was the most decisive of the initiatives.

The subject of torture is much in the book. Many of the protagonists were tortured, when you started in ETA, in the first years you were computer biting the songs of the detainees [details of what the police said under torture] or the testimonies of torture... How does it affect someone?

When I walked in, I started to computerize the organization and take and transcribe the material that my colleagues gave me. And how does it influence? With lots of distances. You have to try to understand what you put there with such a small letter. First you do one, then another, but then over time, if there is a fall, suddenly the testimonies of ten people about their suffering arrive. They were very well made, responding with pens of different colors, because that's how it was done. A jail official who took the prisoner who had just been tortured, helped him write down what happened, what they had done to him, and there was a path that wasn't rice with water and had to get to where he had to go.

"It could be hypothesized: If Spain and France had not used the weapon of torture, where would we be as a people?"

I was touched to do it without being very conscious, although now I do it as a literary figure. I wanted to write poetry and I was writing that other. I transcribed a lot of them, and then I've also read a lot of testimonies.

Torture has been the main method used by the Spanish and French states against those fighting for the freedom of the Basque Country from the beginning to the end. Better said, from before you start, to after you finish. It could be hypothesized, if they hadn't used that weapon, where would we be as a people? Torture is a silent weapon, in which an explosive device is seen. If your main weapon is kept secret, and there is also complicity so that that is so, for example, not to give credibility when you manage to visualize... Even when he arrives in Strasbourg, they punish the Spanish State, but they punish him because he has not investigated the complaint. Torture has been a continuum in my life, which is why it comes out in so many books.

As the main evidence of the Burgos Lawsuit is statements extracted from torture, the Basque Government in exile declared any conclusion unacceptable and the Lehendakari Leizaola summoned the citizens for the first day of strike. How things change...

I prefer to draw your own conclusions.

Beyond Euskal Herria, fighting centered on armed struggle was a global reality in the 1970s... We are talking about a generation. As in Euskal Herria there were also divisions, mines, internal clashes, fluctuating evolutions of fights... Renato Curcio, one of the founders of the Italian Red Brigades, summed up in a book of interviews the contribution of his Italian generation: "Maybe too dogmatic, but very generous." Does your phrase serve Euskal Herria?

I have not known any dogmatic institution. When I entered there was only one ETA, before there were many misgivings. To talk about this, after Burgos there is another key moment in the history of the world: Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This went up to the organizations fighting in the armed struggle with the goal of a purely social change. In Euskal Herria, the struggle continued, but the truth is that the objectives were not the same. Yes, they used crutches, but the goals were not the same, the Italian armed struggles and those of the Basque Country had nothing to do with it. Understanding this costs a lot.

That does not detract from the fact that the militant entering ETA does not have a transformative ideology, but the situation and objectives are not the same. We are an oppressed people, we have no freedom. "They're two sides of the same coin," ha, but one side has more weight or influence.

.jpg)

Most men appear in the book.

Yes, it is something I have tried to express in the book, which obsesses me. There is a very critical line that critiques from militarism to ETA as an armed group. I am not left with the fact that, as in other human groups, there has been no sexual and gender harassment in ETA, but it is worth doing another reading. But for some, that would be to do apology or whatever, and we go back into the field of things that you can't talk about.

And also the authors of the latest works on memory and story mentioned (Gorrindo, Beltza, Bikila, zu zeu...), all of them men.

Of course, it's a scourge, it's like this. So I've also tried to write the book from me, not trying to represent a collective voice.

"If different kinds of zancuds persist, if you don't get a solution, the young people will respond."

To finish, he also tells the story of Marixol Iparragirre, how they murdered their partner, how they tortured their whole family...

Marixol Iparragirre is one of the people who read the manifesto of the disappearance of ETA. I start the book with my parents and end with Marixol. Because I have a personal relationship, it seemed to me that there was something that shaped the book.

"In order for the conflict not to recur, everyone must be able to speak freely and open a process in which all victims are recognized and observed." This was stated a few months ago by Marixol Iparragirre at the National Audience of Spain.

Let's see if someone clings to that, if there's no danger. If the different types of carrots persist, if they are not given a solution, the young people will respond. It's not a threat, it's a constancy, the story is like this. We have the opportunity to fix things. What price do you have to pay for that repair? If someone wants to talk and raise things ...

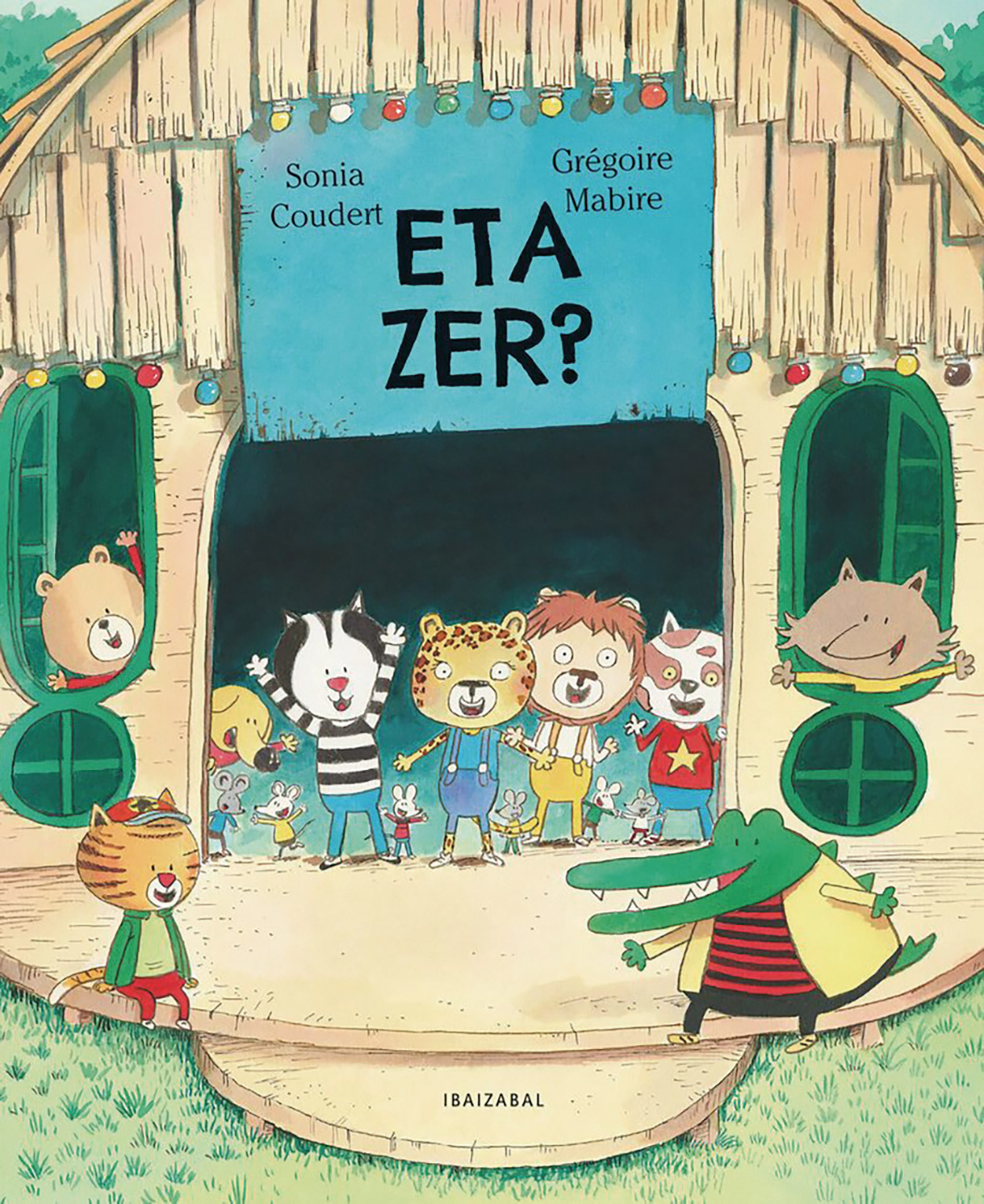

The one who approaches this book, first of all, will be with G. It meets the images of Mabire. They are comic style images, very accurate strokes and celestial experiences that help to easily interpret characters and situations. These images coincide with the text, which is... [+]

The Park of Doña Casilda in Bilbao becomes once a year the meeting point of the street theatre. This year, the Kalealdia festival is 25 years old, and in the first week of July, 86 performances have been seen from 32 different companies.

On July 3, I was struck by the colorful... [+]

18:45. My friends have been quoted by 7 p.m., but the mobile alarm has caught me far from being ready. Dressed in a pajamas with drawings of sandie and looking only at the Google document of the computer, I have admitted that today I will not arrive in time either. However, this... [+]

When I published my first book of poems, they offered me a recital at a university. The musician charged in money and I was given a book about Jorge Oteiza, which I didn't take because I was in my house. This was the first of the unacceptable requests that I have accepted. It was... [+]

For a matter of work, I had to reread this wonderful book. A short book that brings together feminist theory, genealogy and history, and that will surely have a lot of criticism looking on the net and, surprise! I found one, which Irati Majuelo wrote in Berria.El book published... [+]