Matanza de Ategorrieta 1931: The most violent in Euskal Herria

- Pasaitarras fishermen went on strike to improve their working conditions in the newly created Second Spanish Republic. They paid for the skin: detainees, civilian guard shots, seven deaths and dozens injured. In Ategorrieta, when clockhands sounded at 10:00. 90 years after the Ategorrieta massacre. This report has been published by Irutxuloko Hitzak and has been brought to these pages thanks to the free Creative Commons license.

On 27 May, 90 years have passed since the Ategorrieta massacre. Regardless of the war of 1936 and the shooting of Franco, San Sebastian was the largest massacre of workers in Euskal Herria during the twentieth century: The Civil Guard killed seven workers and wounded dozens of people when Ategorrieta's clock needles sounded at 10:00. Although the massacre has not been hidden, it seems that the Donostiarras have forgotten it. In fact, memory is often uncomfortable. However, the Donostian historian Josetxo Otegi has been very focused on the investigation of what happened in Ategorrieta, and his knowledge and knowledge are essential to know this important episode of our history. It is up to us to face the past: What happened in Ategorrieta on 27 May 1931?

The Ategorrieta massacre was not an isolated event, so it is essential to know the context. On April 14, 1931, the Second Republic of Spain was proclaimed in Eibar, and in the exile of King Alfonso XIII, the political regime changed in the Spanish State, where hope prevailed among the different sectors of society. “During the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera the energies were tightened, and suddenly they saw that the dictatorship was becoming weaker: the labor movement began to regain its strength and to resume its demands because there was a great need. When the Republic arrived, the Conservatives felt distress: the king has disappeared and they do not know what is going to come. The workers just upside down: they have great hope; they believe that with the Republic things will improve,” says historian Josetxo Otegi.

.jpg)

The economic crisis must be added to the implementation of the Republic: “In 1929, it was the crash in New York. So, they were in a very severe economic crisis, and the working people were having a pretty bad time,” says Otegi.

The living conditions of the workers were very precarious in the early 1930s. In the port of Pasaia, in particular, they were “very hard”, according to the historian: “Being a fisherman has always been quite tough, but more so at that time. Furthermore, we must be aware that in Pasaia the majority of the trawler fleet came from Galicia, which then moved to live here and became Basque. They came from a harsh situation, and here they also met with a harsh situation.”

However, the Pasaitarian fishermen began to organize themselves to face the harsh conditions of life and work, creating the Union Maritima union. Three were the main demands of the Passover fishermen. First of all, the men who went to fish at the Great Sole asked to win 300 pesetas a month. Secondly, having a holiday a week: “It’s a rather special fishery: you go out with the boat and don’t quickly find the fish. Once you find it, don't stay until the boat is gone or the boat is full. This may be understandable, but they also had very harsh conditions. They asked to rest once a week: if those who worked on the land had Sunday, what did the fishermen have?” Thirdly, they asked that the day should not exceed fifteen hours. “We have to bear in mind that in 1919, very recently, an eight-hour day was achieved in the Spanish State, and these workers twelve years later still spoke fifteen hours,” explains Otegi.

The Passover fishermen were highly politicized. Although the Union Maritima trade union was federated with the UGT trade union, the communists, anarchists, socialists and others were among the fishermen: “Union Maritima did not fully join UGT’s ideology; Union Maritima’s spokeswoman on this strike was Juan Astigarrabia, a well-known PCE militant.”

.jpg)

In April 1931, the fishermen made the three main requests to the shipowners, and after the employer’s refusal, the workers began the strike for the First of May: “The entire trawler fleet went on strike, which would amount to about 3,000 people,” according to Otegi. But the employer tried to frustrate the strike. “The shipowners brought other sailors from Galicia, but they did not tell them that they carried them as a skirole. In some cases, the newcomers responded with dignity and joined the strike,” explains Otegi.

The Government of the Republic tried to lay workers and shipowners around a table and to do bridging work, but the workers maintained their demands: “However, there were also tensions among the workers about the demands. And it's that when I was on strike, they didn't make money, and people were hungry. However, they organized solidarity and maintained the strike,” says Otegi.

In addition, two workers were arrested: “The shipowners could not take the tooling out of the boats in Pasaia, but they took it and took it to Getaria to be used by some fishermen in the area. The workers realized this and practiced some sabotage: they threw several utensils into the sea and arrested two people on 26 May. Juan Astigarrabia went to speak to civil governor Ramón Aldasoro and asked him to release these detainees. Aldasoro told him no and to accept the government’s bridging role,” Otegi explains. Military governor Villa Arbille asked the workers for the same, going to Pasaia personally. The workers did not accept what was said by the Republican authorities and called for the demonstration on 27 May: They were going to go from Pasaia to San Sebastian, under the slogan Pan y libertad, to ask for the freedom of the workers detained, a day of fifteen hours, a holiday and a salary of 300 pesetas. Ramon Aldasoro told them that they would use “all means” to stop the demonstration.

27 May: Day of the massacre

On May 27, 1931, at 09:00, between 1,500 and 2,000 people left Trintxerpe in a demonstration to San Sebastian, where the Civil Government was located. Upon arriving at Miraculous, the army waited for them: “It was common that when there were severe disturbances the army, the Sicilian Regiment, would go out into the street to perform public order functions,” Otegi explains. The workers talked to the soldiers and let them follow, and the same happened on a barrier of the soldiers that followed, but “the soldiers told them to walk carefully because there were civil guards in Ategorrieta, performing the order of not letting anyone go,” according to Otegi. The protesters were waiting for 40 civilian guards in Ategorrieta.

The documentary Trintxerpe: Galicians in Euskal Herria, directed by the filmmaker Josu Iraeta, has the presence of Nemesio Goia, a fisherman in Pasaia who was at that demonstration. This is how the experience told: “We came to Miraculous and the soldiers appeared to us. The sergeant let us move forward, but he told us that later on there was the Civil Guard on horseback. As we were young, we continued. They started firing, and all of us who were in front of us were lucky that, because they were high on horseback, the shots were coming to those in the back. We suffered several injuries and deaths. From there we ran back to Trintxerpe. It was a very sad day for the Trintxerpe neighborhood.”

Seven deaths and dozens wounded

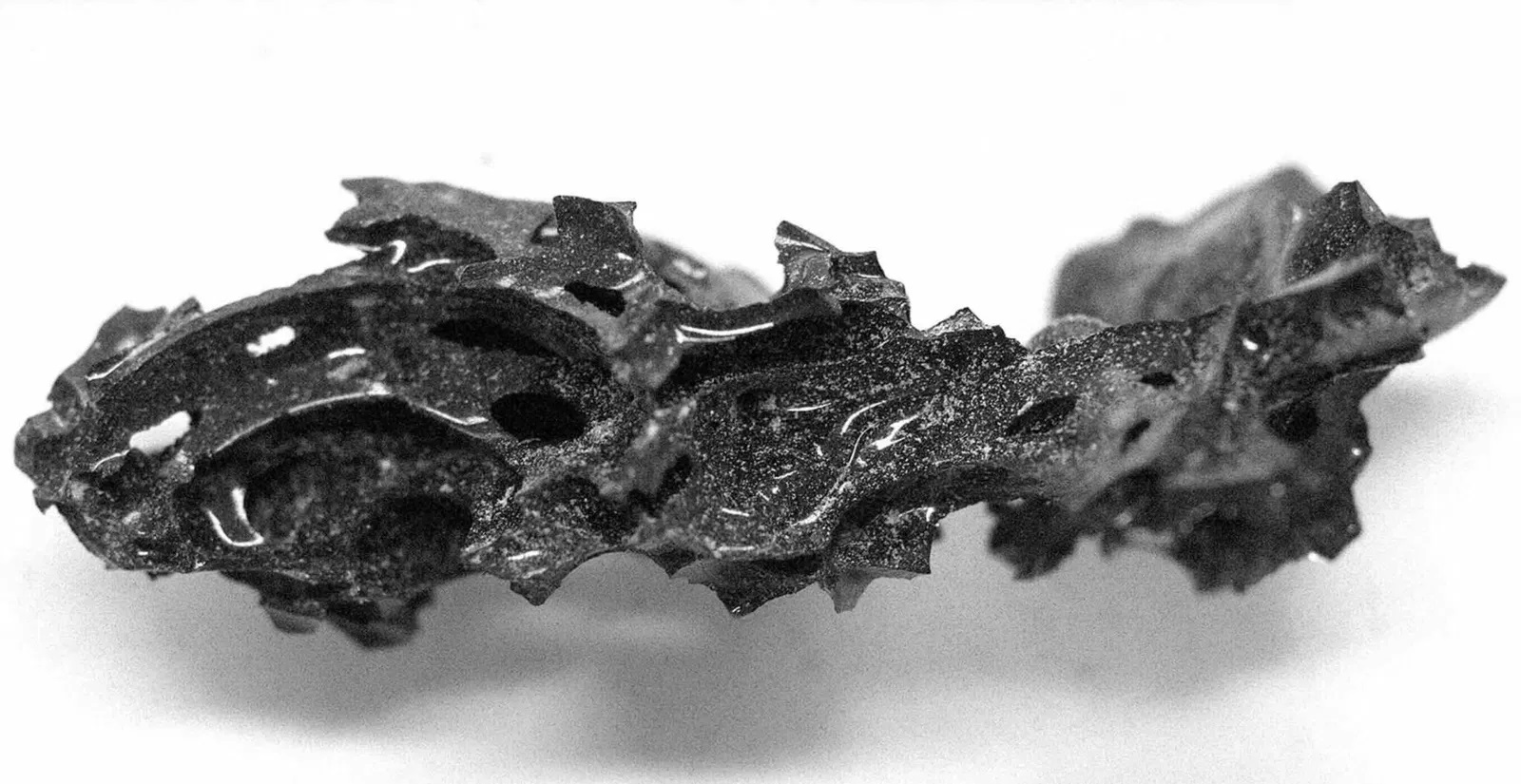

In the Ategorrieta massacre there were seven employees who were shot by the civilian guards: two died immediately, four hours later, and another lost his life on 2 June. The youngest was 19 years old and the oldest 34, were six Galicians and one from Valladolid (Spain). José Carne, Manuel Pérez, José Novo, Antonio Barro, Julian Zurro, Jesús Camposoto and Manuel López. Dozens of women were wounded. “It was a real massacre. With the exception of the 1936 war and the shooting of Franco, it is the hardest massacre in Euskal Herria: It exceeds that of Vitoria [3 March 1976]”, according to Josetxo Otegi.

.jpg)

One of the seven workers killed was José Novo, and his nephew lives in Errenteria today: It is called Cristina Novo and, in her opinion, “it is very important that young people know what happened.”

José Novo was from Galicia, specifically from Santa Eugenia de Riveira, and came to work in the Basque Country: “He arrived in Pasaia shortly before the Ategorrieta massacre took place. The shipowners traveled to Galicia in search of people to work here. When he came here, he realized the problems there were and, seeing that people were on strike, he decided not to go to work. He joined the Basque colleagues and therefore decided to join the demonstration,” explains his niece. Unfortunately, the 25-year-old was shot dead by the Civil Guard in Ategorrieta.

However, family members stayed in the Basque Country. The Novo were 22 brothers and José was one of the first to come: then another five brothers and mothers came to Euskal Herria. Cristina's father came to Trintxerpe after the 1936 war, and then Cristina was born: At Casa Trintxerpe. She currently lives in Errenteria with her husband and two daughters.

Consequences of the massacre

The news of the Ategorrieta massacre spread rapidly in San Sebastian and a general strike was called. “On Garibai Street a tram was turned and the weapon on Avenida de la Libertad was put in a store and tried to take weapons, but municipal police appeared there,” explains Otegi.

“One wrong thing that Ramón Aldasoro did was to consider these kinds of manifestations as an act against the republic: it was not his personal mistake, it was common. They only saw that they questioned the republican authority, and so did those of the PSOE and those of the UGT, who opposed the strike. In San Francisco Street, the PSOE councilman, Guillermo Torrijos, had a firework and went to close a piquet, which said they would not close it. Most of the company's workers belonged to the PSOE and shot inside the pickets with a shotgun: eight were injured, one was serious. There were contradictions between the left: Torrijos was arrested in the district of Egia in 1934, as the top leader of the October revolution in Guipuzkoan. They were in favor and against the armed struggle, depending on their interests,” explains Otegi.

.jpg)

A war situation was established in San Sebastian and the strike continued. The repression against the Communists was obvious: “Eleven people were arrested at a bar in Martutene and named responsible for the massacre in the press,” says Otegi.

Finally, the demands of the workers were approved.

Finally, however, the shipowners accepted the demands of the fishermen and reached an agreement. “The fishermen returned to work a few days later, because they got more or less the demands. After what happened, the government could not act as if nothing had happened, and after the massacre, letting the owners come out with it would be a very bad image, although the republic never realized it was communist neglect. The government of the Republic pressured the shipowners to accept the demands of the fishermen,” according to Otegi.

However, within the Union Maritima Union there were political divisions: “The discrepancies between socialists and communists were accentuated: Union Maritima was federated with UGT and then went into the CGTU created by the Communists. Anarchists said the communists were irresponsible.”

On the other hand, what happened to Ramón Aldasoro? Despite being the first Republican civil governor of Gipuzkoa, civilian guards fired on orders at Ategorrieta. In 1936, Aldasoro was Trade and Supply Advisor to the first Basque Government in history, on the eve of the 1936 war. The Autonomous Government Public Works Advisor was Juan Astigarrabia, spokesman for Union Maritima five years earlier. Therefore, Aldasoro and Astigarrabia were part of the same government, five years after the Ategorrieta massacre.

After the 1936 war and Franco, dark times covered the Ategorrieta massacre. Let us not forget our history.

Atapuercako aztarnategian hominido zahar baten aurpegi-hezur zatiak aurkitu dituzte. Homo affinis erectus bezala sailkatu dute giza-espezieen artean, eta gure arbasoek Afrikatik kanpora egindako lehen migrazioei buruzko teoriak irauli ditzake, adituen arabera.

Chão de Lamas-eko zilarrezko objektu sorta 1913an topatu zuten Coimbran (Portugal). Objektu horien artean zeltiar jatorriko zilarrezko bi ilargi zeuden. Bi ilargiak apaingarri hutsak zirela uste izan dute orain arte. Baina, berriki, adituek ilargietan egin zituzten motibo... [+]

Hertfordshire (Ingalaterra), 1543. Henrike VIII.a erregearen eta Ana Bolenaren alaba Elisabet hil omen zen Hatfield jauregian, 10 urte besterik ez zituela, sukarrak jota hainbat aste eman ondoren. Kat Ashley eta Thomas Parry zaintzaileek, izututa, irtenbide bitxia topatu omen... [+]

Kanakyko Gobernuko kide gisa edo Parisekilako elkarrizketa-mahaiko kide gisa hitz egin zezakeen, baina argi utzi digu FLNKS Askatasun Nazionalerako Fronte Sozialista Kanakaren kanpo harremanen idazkari gisa mintzatuko zitzaigula. Hitz bakoitzak duelako bere pisua eta ondorena,... [+]

Urte bat beteko da laster Pazifikoko Kanaky herriko matxinada eta estatu-errepresiotik. Maiatzaren 14an gogortu zen giroa, kanaken bizian –baita deskolonizazio prozesuan ere– eraginen lukeen lege proiektu bat bozkatu zutelako Paristik. Hamar hilabete pasa direla,... [+]

Hiru bideo dira (albiste barruan ikusgai). Batak jasotzen du, grebak antolatzea leporatuta, Carabanchelen espetxeratu zituzten Jesús Fernandez Naves, Imanol Olabarria eta Juanjo San Sebastián langileak espetxetik atera ziren unea, 1976ko abuztuan. Beste biak Martxoak... [+]

Otsailean bost urte bete dira Iruña-Veleiako epaiketatik, baina oraindik hainbat pasarte ezezagunak dira.

11 urteko gurutze-bidea. Arabako Foru Aldundiak (AFA) kereila jarri zuenetik epaiketa burutzera 11 urte luze pasa ziren. Luzatzen den justizia ez dela justizia, dio... [+]

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

79. urtean, Vesubio sumendiaren erupzioak errautsez eta arrokaz estali zituen Ponpeia eta Herkulano hiriak eta hango biztanleak. Aurkikuntza arkeologiko ugari egin dira hondakinetan; tartean, 2018an, gorpuzki batzuk aztertu zituzten berriro, eta ikusi zuten gizon baten garuna... [+]

Luxorren, Erregeen Haranetik gertu, hilobi garrantzitsu baten sarrera eta pasabide nagusia aurkitu zituzten 2022an. Orain, alabastrozko objektu batean Tutmosis II.aren kartutxoa topatu dute (irudian). Horrek esan nahi du hilobi hori XVIII. dinastiako faraoiarena... [+]

AEB, 1900eko azaroaren 6a. William McKinley (1843-1901) bigarrenez aukeratu zuten AEBetako presidente. Berriki, Donald Trump ere bigarrenez presidente aukeratu ondoren, McKinleyrekiko miresmen garbia agertu du.

Horregatik, AEBetako mendirik altuenari ofizialki berriro... [+]

Andeetako Altiplanoan, qocha deituriko aintzirak sortzen hasi dira inken antzinako teknikak erabilita, aldaketa klimatikoari eta sikateei aurre egiteko. Ura “erein eta uztatzea” esaten diote: ura lurrean infiltratzen da eta horrek bizia ekartzen dio inguruari. Peruko... [+]

1936ko Gerran milaka haurrek Euskal Herria utzi behar izan zuten faxisten bonbetatik ihes egiteko. Frantzia, Katalunia, Belgika, Erresuma Batua, Sobietar Batasuna eta Amerikako herrialdeetara joandako horien historia jasotzeko zeregin erraldoiari ekin dio Intxorta 1937... [+]