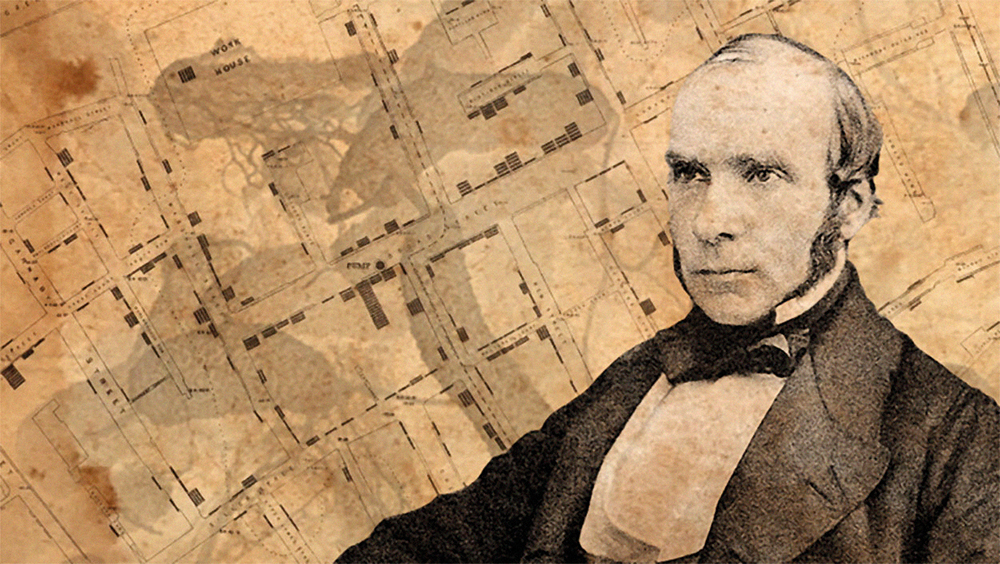

Precursor of cholera plague with maps

- London, 1848. The cholera epidemic spread throughout the city and doctors were divided into two camps due to the origin of this and other diseases.

Most physicians continued to rely on miasmatic theory. According to this theory, which came from ancient times, the miasmas, which in Greek is pollution, produced a series of diseases, that is, smelly emanations of soiled lands and waters. Others began to defend Louis Pasteur's new microbial theory. The latter included John Snow (1813-1858). Born within a family of peasants, the cholera that spread among the Killingsworth mining coal in his youth witnessed a terrible plague that led him to fight the disease and study medicine for it.

In that 1848 cholera outbreak, Snow used an innovative method. He did not visit the sick at home, placed the cases on a map and concluded that most of the sick and dead concentrated around public or private water pumps. It was the first time that the geographic method was used to study an epidemic. The following year he founded the pioneering London Epidemiological Society with other doctors.

In 1854, another outbreak of cholera allowed him to continue the investigation. In the Soho neighborhood, half a kilometer in diameter around Broad Street, it caused more than 700 deaths in a single week. He took a map of Soho and, with the help of the parish priest and the archive of the Middlesex hospital, he placed all the deaths in September. He found that the epicenter of all the points on the map and, therefore, the origin of the outbreak was the Broad Street public bomb. He got the authorities to close the bomb and the plague stopped immediately.

Years later, members of the London Health Council decided to re-believe in the myasthmatic theory because they were unwilling to invest to ensure the water supply in Soho. The Broad Street bomb was reused and cholera came back stronger than ever to Sohora. Even though John Snow was already dead, hundreds and hundreds of people who caused cholera were right.

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

Indartsua, irribarretsua eta oso langilea. Helburu pila bat ditu esku artean, eta ideia bat okurritzen zaionean buru-belarri aritzen da horretan. Horiek dira Ainhoa Jungitu (Urduña, Bizkaia, 1998) deskribatzen duten zenbait ezaugarri. 2023an esklerosi anizkoitza... [+]

Pazienteek Donostiara joan behar dute arreta jasotzeko. Osasun Bidasoa plataforma herritarrak salatu du itxierak “are gehiago hondatuko” duela eskualdeko osasun publikoa.

EAEn BAMEa (famili medikuen formazioa) lau urtetik hiru urtetara jaistea eskatu du Jaurlaritzak. Osakidetzaren "larritasunaren" erantzukizuna Ministerioari bota dio Jaurlaritzako Osasun sailburu Alberto Martinezek: "Ez digute egiten uzten, eta haiek ez dute ezer... [+]

Sare sozialen kontra hitz egitea ondo dago, beno, nire inguruan ondo ikusia bezala dago sare sozialek dakartzaten kalteez eta txarkeriez aritzea; progre gelditzen da bat horrela jardunda, baina gaur alde hitz egin nahi dut. Ez ni optimista digitala nauzuelako, baizik eta sare... [+]