It's ecology, it's nonsense!

- How much is biodiversity worth? It can be said that the climate in full emergency and Covid-19 in the ravaged world, yet it is hard for us to be aware of the cost of the destruction of nature. A report by economist Partha Dasgupta is flying because she warns that we are reaching an irreversible limit. According to this, we should avoid indicators such as Gross Domestic Product and put biodiversity at the centre of the economy.

Henry Way Kendall (1926-1999) was a climber, as well as a Nobel Prize in physics, and he learned in the grooves on the walls of Yosemite to appreciate in the open air what he could not in the labs until he fell and died while photographing the cascade of a Florida cave. In 1992 he wrote a warning to Humanity, signed by 1,700 other scientists, saying that “we were going to collide with human beings and nature.”

Twenty-five years later, in November 2017, scientists around the world published another document: the second warning. On this occasion, more than 15,000 firms have received the greatest support that a scientific article has had in history. According to this, we have not yet done our homework, including revising the economy based on unlimited growth or restoring ecosystems. We walked to an unknown place with no return.

This is precisely the main conclusion of the study that we have heard from the economist at Cambridge University, Partha Dasgupta, who has irreversibly affected many ecosystems, from coral reefs to tropical rainforests or mountains adjacent to the house, and that we are about to cross that “tipping point”.

On behalf of the UK Finance Ministry, which has read well, reader, this time it is not an initiative that has emerged from the office of the Environment Department, the ambitious 600-page report has been made public in February. Of Indian and British nationalized origin, Dasgupta has a long and prestigious trajectory in the field of social sciences, especially investigating the depletion of natural resources in developing countries. In the report (pdf) the stick stands in front of the current system: “As the biosphere has borders, so does the global economy,” and believes that this has consequences “legitimately in what we expect from the human enterprise.”

Investing in socio-ecological resilience

In the times ravaged by Covid-19, members of the Basque scientific community have also expressed their opinion in various media during the month of February, “in favour of the ecological reconstruction of the economy”. The “syndemia” that, according to them, we live has revealed the vulnerability of the economic system and the existence of “eco-dependent” human beings.

Scientists, citing Dasgupta, state that “investing in socio-ecological resilience” is necessary. In other words, we must increase the capacity to adapt to the situations of shock that this global crisis will bring us, building a strong social network of mutual care and fostering a healthy environment. In this resilient future, the inertias of an old economy that fosters hypermobility and “iconic infrastructures” do not fit in with other needs of the population, such as the APR.

The Indian economist’s report does not take long to sound, many have called it the “new Stern report”. Nicholas Stern wrote in 2006 on the impact of climate change on the global economy and was a milestone in putting the costs of “doing nothing” against global warming for the first time.

Dasgupta has gone one step further and put biodiversity at the heart of the economy. “He has given us the northern needle we needed,” says the renowned British naturalist and writer David Attenborough in the preamble.

Some data are, at least, revealing. Compared to the average of the last tens of millions of years, the rate of species disappearance today is between 100 and 1,000 times higher. Globally, 100 out of every million species are disappearing in the world and in the coming decades 20% of species would disappear: “These figures put into perspective the same importance as the presence of humanity in the biosphere, and show us why scientists and ecologists claim that it is the sixth major biological stratum since the beginning of life,” says Dasgupta.

Need to exceed the GDP indicator

Currently, only 4% of the mammals that live in the world are “wild”, the rest being composed of domesticated livestock and humans. In 1950, 2.5 billion people lived on our planet, and today we are about 7.7 billion Homo Sapiens. Economic activity has multiplied by 13 and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has multiplied by 15.

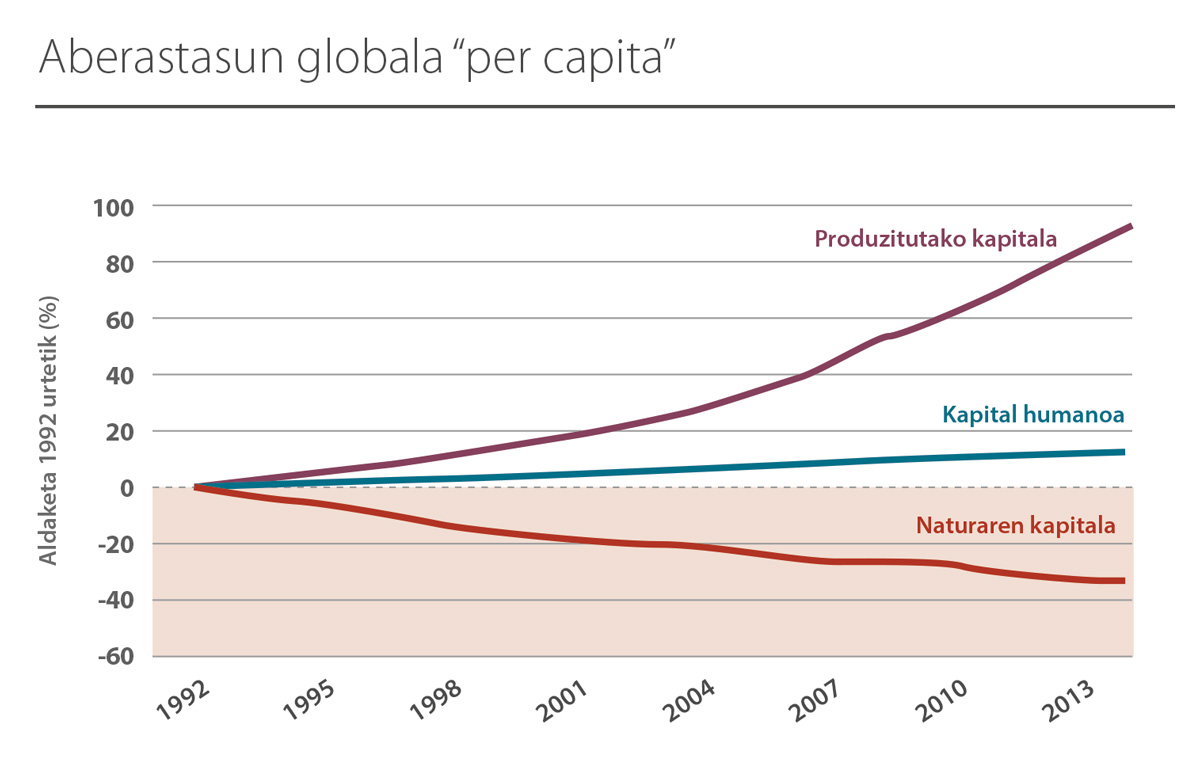

However, this economic growth has been achieved by eliminating ecosystems, according to the economist: Between 1992 and 2014, the “produced capital” per capita (buildings, machinery, infrastructure…) has doubled, the “human capital” (education, health, capacity…) has grown by 13%, but that other asset that does not receive the annual accounts, the “nature capital”, has decreased by 40% in those years (see infographic).

Dasgupt's report remembers research published by Science. According to this, these “biosphere services” or nature capital had a value of 33 billion euros in the 1990s, twice as much as world GDP: “It could be thought that with this data we should take into account the importance of the biosphere in the economy, but that was not the case.” In fact, the value of the biosphere is not appreciated in market prices, as it is available to all without monetary cost. This value has nothing to do with short-term results, “but with the well-being of man and thousands of other species.”

GDP creator Simon Kuznets himself said that this macroeconomic indicator does not measure human well-being. He created GDP after the crack of 1929 or the Great Depression, but to do U.S. national accounting. Since the 1940s, however, it began to be used for the economic ranking of the countries of the world and has served as the basis for other indicators such as the Human Development Index used by the United Nations.

Reproductive work, the shadow economy, the quality of education, social equality… All this is not reflected in GDP or natural heritage. Dasgupta defends in his study the overcoming of this indicator, “because it leads to unsustainable growth and economic development”, and proposes to replace it with an idea of “inclusive” wealth that contemplates biodiversity and improves the well-being not only of the present, but of the future.

We pay to exploit nature

In addition to making a diagnosis of the situation, the person responsible for it puts the work done for the British Government in some way at stake. Thus, it can be read that “governments in almost every place of the world aggravate the situation by paying more to people than to protect nature.” In this respect, the report recalls that fossil fuels, estractivism, overfishing, intensive farming, polluting livestock, such as big jeans, are subsidised.

Compared to the average of the last tens of millions of years, the rate of species disappearance today is between 100 and 1,000 times higher.

Dasgupta also tells us about the role of technology. Although he considers it important to reduce the ecological footprint of human beings, he believes that “we cannot rely solely on it”. We will not find miracles in electric cars, digitalized cars, hydrogen, etc., we will have to radically “restructure” the current patterns of consumption and production. To maintain the current lifestyle of people in high-income countries, we would only need 1.6 planets like Earth.

And, of course, those who lose the least are the ones who lose the most, as we rise their natural heritage. This is not just a demographic or technical problem, it has a lot of geopolitics. Food sovereignty programmes must be put in place in poor countries, women’s access to financial resources must be increased, sustainable activities and consumption promoted… rather than asking for sheep’s hair. The Dasgupt report makes this clear: it will cost us less to act as soon as possible in favour of biodiversity than to leave the measures for later.

Biologian doktorea, CESIC Zientzia Ikerketen Kontseilu Nagusiko ikerlaria eta Madrilgo Rey Juan Carlos unibertsitateko irakaslea, Fernando Valladares (Mar del Plata, 1965) klima aldaketa eta ingurumen gaietan Espainiako Estatuko ahots kritiko ezagunenetako bat da. Urteak... [+]

Nola azaldu 10-12 urteko ikasleei bioaniztasunaren galerak eta klima aldaketaren ondorioek duten larritasuna, “ez dago ezer egiterik” ideia alboratu eta planetaren alde elkarrekin zer egin dezakegun gogoetatzeko? Fernando Valladares biologoak hainbat gako eman dizkie... [+]

Nekazal eremu lehor baten erdian ageri da putzua. Txikia da tamainaz, eta ez oso sakona. Egunak dira euririk egiten ez duela, baina oasi txiki honek oraindik ere aurretik bildutako urari eusten dio. Gauak eremua irentsi du eta isiltasunaren erdian kantu bakarti bat entzun da... [+]

Eskoziako Lur Garaietara otsoak itzularazteak basoak bere onera ekartzen lagunduko lukeela adierazi dute Leeds unibertsitateko ikertzaileek.. Horrek, era berean, klima-larrialdiari aurre egiteko balioko lukeela baieztatu dute, basoek atmosferako karbono-dioxidoa xurgatuko... [+]

_Glaciar.png)