"I'm an old totem"

- In 1969, Jorge Herralde launched Anagram, an institution among Spanish-language publishers. Retired in 2017, and at the age of 85, follow the journal of the publisher closely, as he has recognized us in his house in Barcelona.

For readers who already have an age without being older, who call such a pompous middle age, which is condemnation, Anagram is one of the referent editorials in Spanish, if not referents. A quick review of the shelves of the house ensures it. Because the first thing I do when I walk into another's house is to look at the library -- and I know that this risks me not being invited anymore -- in the hope of finding yellowish, grayish, black books that will make me feel at home.

Already in my work for the most important cultural supplement of Euskal Herria, now missing, I had the opportunity to interview a beautiful selection of writers, I don't know if worldwide, at least international, upper-middle class, many of the Anagram group: Jonathan Coe, Jean Echenoz, Alan Pauls, Juan Villoro, for example, closer to the Catalans Quim Monó or Sergi Pàmies, all men, negative point. Not few of them marked my career, not only in the professional, but surely in the staff. With all this I mean that my reading life, and in general life, very different, I think it would be worse if Anagram had not existed.

With this heavy backpack, we have touched the bell of editor Jorge Herralde, of an elegant house located in the upper part of Barcelona, in a sunny midday spring. Lali Gubern, her wife, her assistant, her mentor, has opened the door to us -- which, from a corner, your husband, will accompany you, will continually point you, a name here, a date there. Shortly after passing to the living room for the guests, Herralde has appeared calmly, another interview!, a copite in his hand; at first I thought full of wine, but by the hour, and by the turbulent color of the liquid, Martinia could be quiet.

.jpg)

Sitting, he enlists the journalist and lets down the joke of not being able to speak in Basque, the boring Spanish word begins, easily jumping into Catalan and interspersing French, Italian or English expressions naturally. “I want to change language.” For a moment it seems that we are in any hallway of the Frankfurt book fair. I find it hard to imagine before me that I have a person who has accumulated 50 years of experience, who has published over 4,000 titles, a builder of a catalog that for many is already unforgettable.

From politician to literature

The five-decade editing work on the back is difficult to decide when to retain. The first decade, from the birth of the editorial to the disenchantment that brought the Spanish political transition, “was an era of great illusion, but also of great cracks, a continuous clash with censorship” (nine books were kidnapped to Anagram, four of them after Franco’s death). “And one day I managed to pass a book by surprise, “On the Psychology of Military Incompetence,” which I sent to Lt. Gen. “Intimate Friend Muñoz Grandes” by Franco. Asked if the publisher was more red and radical than the editor at the time, Herralde replied yes, “but this editor was the one who pulled out those books, taking all the risks.” He recalls the flower that was cast in Manolo Sacristan, the Catalan communist pop of the time, according to him “was the most left editorial in Spain”.

Changing the political situation, they experienced a great crisis that jeopardized the very survival of the publisher: they had economic problems with the distributor, burned offices for the far-right and, above all, began to lower the sale of the political book from 1977 onwards. “The readers of these kinds of books disappeared, almost overnight, after the PSOE won the elections: some went to India, others began to puncture, the political books remained in the dust store.” It followed the trend to literature, had been published by Charles Bukowski, Tom Wolfe, but the political books were covered. The literature is going to know a certain liberation in those years, and to some extent the editor.

“The readers of these kinds of books disappeared, almost from day to day, after the PSOE won the elections: some went to India, others began to puncture, the political books remained in store”

The Panorama of Narratives, which began in 1981, is the case of the Hispanic Narrative collections, which began in 1983. Those who gave the editorial a real boost and made it acquire the central place it has occupied in the next four decades in the Spanish literary system. The first, “a kind of Du monde entier collection of the editorial Gallimard”, that is, a collection of world-class writers in Spanish, with those yellow identifiers, which the editor of the Planet called “yellow fever”. Many works and authors have been published in it that have become contemporary classics and were originally completely unknown, such as the British Dream Team (Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, or the Nobel Prize Kazuo Ishiguro).

The second collection takes advantage of greyish skins and shows authors writing in Spanish. Carmen Martín Gaite, Alvaro Pombo, Soledad Puertolas or Rafael Chirbes have grown there – “Their beginnings were doubtful”, says the editor – and more recently Marta Sanz and Sara Mesa. Latin American writers also highlighted Chilean writers Roberto Bolaño. “The authors have given me more satisfaction, they are the real protagonists of the edition, and I have tried to maintain a close relationship, not only professional, I can go quietly to take a drink with them”. Thus, Anagram has managed to change and consolidate the contemporary panorama of reading in Spain over the last 40 years.

.jpg)

Basque writers

What has surely been the most important editorial in Spanish, instead, began with a book in Catalan. “By chance”, with two books provided by each collection, but L’de viure de Cesare Paves (The Trade of Life) and Tristos tròpics (Sad Tropics) by Claude Levi-Strauss first came, “two terrible books”, by April 23, 1969. The Catalan collection was not successful, but they did not sell 300 copies of the book, “being masterpieces”. The collection was interrupted with five titles. “It seems that in those years there were no people to read books translated into Catalan.” In 2014, the Llibres Anagram collection was launched in Catalan, with original authors – Irene Solà, Mercè Ibarz – and translations. Now it seems that there are also people who are willing to read the translations in Catalan.

Opening the melon of so-called peripheral literatures, I have quoted the total absence of the authors who have written in Basque. “In those years the only name we heard was Bernardo Atxaga. And it was taken, of course.” There are Basque authors who do not write in Basque in the catalog of Anagram, such as Marie Darrieussecq or Miguel Sánchez-Ostiz (“I have published several great books”). At the time I did not remember that Hasier Etxeberria also had a close relationship with the publisher, to the point of interviewing Paul Auster in the ETB Sautrela literature program, “Jorge Herralde is really a great editor, no doubt,” wrote Etxeberria. And I have not dared to say that every major writer and Basque friend has always dreamed of publishing in Anagram, in the Panorama of Narrations with yellowish lids, of course.

So far we have talked about the editor Herralde, but with his own name he has already published three books that come to show that the editor is a frustrated writer and that he is willing to bear witness to his work in 50 years. “Well, the editor is also, to some extent, a writer: our books would be the words of the writer and the catalog the novel.” He has just published a new book, The Herralde Papers (The Herralde Papers), written by him incorrectly: Along with the story of Anagram, by essayist Jordi Gràcia, you can read dozens of letters written and sent by Herralde himself, directed by writers, other editors, literary agents, literary critics. “It seems that letters have aroused interest, it will not be very common to see an editor fighting with literary people.”

"Bad books?" '97; What a caress! All I've been interested in is publishing not only good books, but also relevant books. I think I haven't let good books go."

It is not very common, far from it, that knowing the hermetism of the editorial system, internal conflicts, numerical accounts, personal contingencies are seen this way. It is not very common to discover a letter from Herralde to literary critic Rafael Conte: “I have just read, with the vote you can imagine, that defines my work as an editor from your pulpito in El País: ‘Anagram is committed to light literature’. Despite the hardness of some letters, “I have never been overhead to deny greetings to anyone, or to close a door for negative criticism.” The opposite would have happened, and someone would have given the door blow to the relationship with Herralde, like the writer Javier Marias, who has been so notorious the public enemy between the two.

The task of an editor

However, is the task of an editor this task of marking? As a writer is asked to be above criticism, if it is ugly for a creator to drown the work of the critic, does the editor have to go down to those barros? There are also, of course, negative myths about Herralde: unfair contracts, unbearable treatment, the shattering of progress. And there are also those who tell the story of Anagram according to the enemies of Herralde: in the first stage were Franco and disillusion; in the second, El País and agent Carme Balcells. If an editor is defined more than by the books he has published, by which he has not published, there may be a real value of these letters in what they do not show.

But what more regrets the editor, the good books he hasn't published or the bad books he's published? “Bad books? '97; What a caress! All I've been interested in is publishing not only good books, but also relevant books. I think I haven't let good books go. There have been good books that I haven’t been able to publish, that’s right, because usually the big editorial groups have made out-of-place deals.” In fact, the incorporation of large business groups into the publishing world in the late 1980s represented a paradigm shift. “These groups may belong to television channels, bookstores, etc., and paying barbarity for a writer does not hurt the economy. But we also overcome it.”

.jpg)

Someone can see Anagram as a great publisher, even now since Herralde sold his shares to the Italian group Feltrinelli in 2014. “Anagram is an editorial that changes ownership but remains independent, as always, but with a new direction.” The policy of the editorial has been not to go fishing for the youngest: “No small editor can say I’ve taken an author from him.” It continues, therefore, with its vocation as a small editor, medium billing and large literary publisher. Although the editor itself has also changed, as Herralde retired in 2017. “I was able to choose Silvia Sesé and I am very happy. We have a perfect relationship, we talk a lot, he tells me things, I tell him. Now I am an old totem in Anagram.”

He has confessed to us a lot that he has read especially in this last year “perhaps more than ever”. Memory books, memories, editors, editors, writers; “I am an insatiable padding.” Of course, also Anagram's books. It doesn't lose any thread. Some say that the publisher is no longer what it was. He has lost the influence and spirit of yesteryear. It is at the center of the respectable, right and discreet at present, losing the critical, provocative, transgressive spirit of the past. Other publishers now occupy that place that Anagram has occupied for decades. “Who knows. Turning 50 and being as it is, I find it a great success, however much the editorial moves tomorrow.” Before concluding the interview and leaving Herralde's house, I told him that I am going to send him the result of what we have talked about in Spanish. “You don’t have to. I trust. Then we’ll talk, if needed.”

Perhaps we could say that this text is the result of an appraisal meeting. However, valuation meetings often leave a dry and bittersweet taste in the mouth. It's a sunny Tuesday afternoon. 16:53. We've connected to the valuation meeting, and we've decided to put a lemon candy in... [+]

I'm talking about Interview. With water and sand

Authors: Telmo Irureta and Mireia Gabilondo.

The actors: Telmo Irureta and Dorleta Urretabizkaia.

Directed by: Assisted by Mireia Gabilondo.

The company is: The temptation.

When: April 2nd.

In which: At the Victoria Eugenia... [+]

On March 7, the 150th anniversary of the birth of Maurice Ravel, the best Basque composer of all time. And in LA LUZ a tribute was paid to this composer, recalling the influence of the famous Bolero on the collective imagination.

By chance, Deutsche Grammophon has just released... [+]

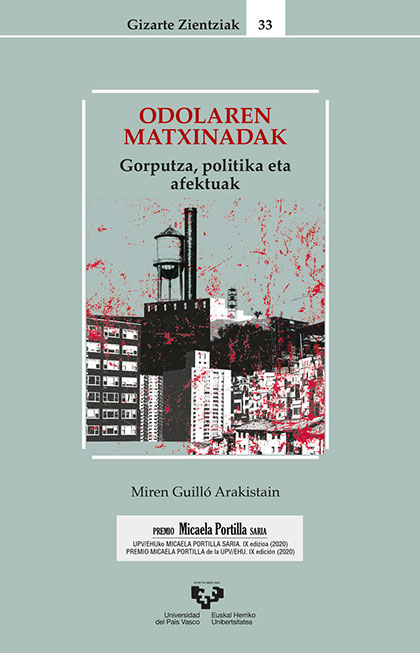

Odolaren matxinadak. Gorputza, politika eta afektuak

Miren Guilló

EHU, 2024

Miren Guilló antropologoaren saiakera berria argitaratu du EHUk. Odolaren matxinada da izenburu... [+]

Lantegia espazioa, Esperantza liburutegia, Arte Ederren Museoko eta Euskal Museoko lanak, Urdaibaiko Guggenheim proiektua... Ugari dira Bilbon eta Bizkaian kulturaren ikuspegi utilitarista eta pribatizazioa agerian uzten dituzten adibideak. Alde Zaharreko haur eta gazteentzako... [+]

The lights of the theater are on. Discreetly, I’m walking on the steps: the school performance is about to begin. The young men run to their seats, full of life and joy. The retreat has the taste of liberation, but this feeling of freedom speaks Spanish or French. This... [+]