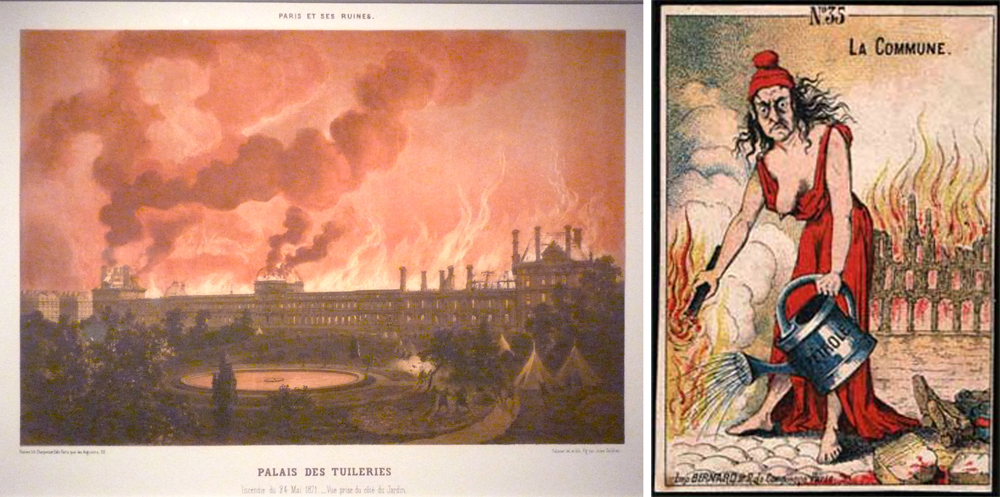

'Pétroleuses', myth of the Paris Commune

- It's been 150 years since the Paris Commune was formed in 1871. After two months, the toilets were persecuted and numerous buildings burned. The authorities called the Pétroleuse women who were attributed fires using the ignition oil. Hundreds of people were arrested and many died without trial. But what were they? Were they themselves the ones who gave fire to the city of fireworks? What did the conservatives of Versailles want to achieve by doing against them?

Paris, 28 March 1871. Ten days after the people rose up, the Paris Commune was formed, considered the first government of the working class. The Loialists severely repressed the Community and, two months later, on 28 May, the government was suspended. This last week of May was called Bloody Week: thousands of toilets were arrested or executed without trial. And in the hostilities, Paris caught fire.

The blame for these fires was mainly attributed to pyromanas in favor of the Pétroleuse or the Toilet. They were told that they were using oil to ignite fires. At the end of the bathing, hundreds of people were arrested and transferred to Versailles for trial there; many others were killed without trial. And in the coming months, the sale of combustible liquids in the capital was banned to prevent oil tankers from returning to business.

Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray (1838-1901) witnessed the event and noted the chronicle of the W.C. Write the following about the presumed bonfires: “Any badly dressed woman, carrying a milky or empty bottle, was considered a Pétroleuse, took her clothes hard, put her on the nearest wall and threw her to death right there.” Therefore, the chronicler questioned from the very beginning the guilt of these women. But Lissagaray was a revolutionary socialist, a communal, so his “biased” vision was not taken into account for a long time. In the same decade of 1870, writer Maxime Du Camp published a “more objective” chronicle of the Community, in which she also denied the participation of pétroleuse. But the myth continued to grow.

At the end of the twentieth century, the declassification of the documentation on the Bathroom allowed historians to delve into the phenomenon of the Pétroleuse, confirming what Lissagaray said in the last century. Robert Tombs and Gay Gullickson, among others, worked on the documentation study and found no case demonstrating that the pétroleuse had produced fires. At the end of the bath, only a few of the hundreds of women tried in Versailles were condemned for actions in favour of the toilet, but none related to the fires. The responsibility for these bloody week fires is now attributed to the conflict itself and, therefore, to both sides.

According to Gullickson, the Pétroleuse myth was part of the propaganda campaign of the politicians of Versailles. It was a gesture against bathing reforms, as some of the measures taken in those few weeks slightly improved the situation of women. In addition to the practical victory on the streets, the conservatives sought a moral victory over those barbaric and devastating toilets.

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]

The title of Communal Luxury suggests a controversial definition of luxury, beyond the conventional connection between luxury and big capitalists. It brings us to the head of the Italian autonomous movement, how it denounced in the 1970s the pretension of limiting workers’... [+]

An apocryphal anecdote says, and Kristin Ross picks up at Communal Luxury that on the seventy-three day of the Russian Revolution, when the Paris Commune passed the 72-day border, Lenin danced on the snow in front of the Winter Palace. Soviet historiography perfectly explores... [+]