"The works of authors from all over the world translated into Basque are part of the Basque literature"

- The editorial Igela, a reference in the literature translated into Euskera, is celebrating thirty-two years this year. The translator Xabier Olarra has worked since its creation as editor and manager. In August last year, in the midst of a pandemic, he replaced Lander Majuelo. With the excuse of the relay we have met in the park of the Taconera de Pamplona to talk about the trajectory of the editorial and Olarra so far and the intentions of Majuelo.

Does the love of literature come from home to you?

Xabier Olarra: In our house there were few books besides those of the school, but our grandfather was very caring and he recited to us the fables of Esopo that he knew in memory, so we learned when we were between six and eight years old. Then, in adolescence there is an interest to know other worlds and to know other stories. I read everything, not books specifically intended for teenagers, which I hadn't read much at the time. Then, at the age of 16-18, reading for some is almost the most important thing, as for others is football. What did I like about the Basque literature? [Gabriel] Read Aresti and [Jon] Mirande. And he did what we had to read at the university that was fond of the literature of the other world, but also what we liked and what we read without further.

Lander Majuelo: In our house yes, being a master mother and a teacher father, at home there have always been many books. I think I started with imitation, because at home I was always reading someone. My sister [literary critique and translator Irati Majuelo] and I have read enthusiastically. I have the memory of reading a lot as a kid, I don't know what kind of stories would exist, and a lot of comics, and when I suspect how those horny books adults read, I started with them, long before I understood them. Then, at 14-15 years old, moved by curiosity and enthusiasm, you jump from a reference you take in a book to the next book and don't stay.

You mentioned Mirande and Aresti, Xabier. Were you about to make a thesis about Miranda, no?

B.O. : When I was thinking about doing the thesis, I went to Bordeaux to take the PhD course. I wanted to make a kind of comparison of the paths of those two poets. But there the road completely deteriorated. It gets worse or better, who knows. There I started reading a lot of black novels in French and English, and also in Spanish. One day I thought I'd start returning them, and that's where I started. The first book, which he always calls Postman, translated it twice there, and the second one, 1280 souls. Elkarri published, then still Igela and none of that in my head. There came a certain idea.

At the same time he published the anthology of Mirande's poems. Did it start to translate and edit at the same time?

B.O. : Then I had no intention of doing anything as a company in the editing world, I thought it was the most Kafkaesque. But I knew that if Elkarri wore a book a year, they would probably publish it, but I didn't think it was enough. It seemed to me that it took hundreds of black novels in Basque to make my students of the time able to read. So naively, we left, not knowing which black hole we could put in. Black, but you'd see a lot of glitter dots, far away.

So Igela starts from the need to have books translated into Euskera?

B.O. : The need was enormous. We gave the students 100 meters, because every day it starts and another two or three Basque novels, and they forced them to read poems like a poem by Aresti... It was necessary and it did not exist. We were two teachers of the founders of the [frog] and we started from that need. That was a starting point, but we did not settle for it, we have to open up a little perspective. In view of what was at the time in the translation world, the needs were much greater. Hence the appearance of EIZIE [in 1988] and of Universal Literature [in 1989]. We, too, set ourselves on that path.

You said that the editor's work touched you when it came to creating the Frog.

B.O. : I was the one who made the decision and proposed it to others, and I had, to put it in some way, the responsibility to do so as quickly as possible and to find colleagues for it, because what we could do as a professor and another translator in the Government of Navarra was very limited, although all day it was dedicated to it. That's the job of editor: look for translators, correctors and potential collaborators, and look for ways to get people what's been done. This leads to more than one head breaker. Because it's hard to translate and publish a book, but then selling is something else. And to learn that, we've taken 30 years.

What has happened to the decision to take over?

B.O. : Thirty-one years of translator or worker, or of another ten years if he had been alone in that, but a company of this kind, although small, requires a lot of work in this style: taking charge of monetary accounts, management, etc., and after thirty years it becomes the burden of Christ. On the other hand, because there are people who can do that work and the same as us with the approaches then. You can guess new paths or you can better adapt to new paths. We had life fixed and that's what we were doing with a hobby, but it seemed to me that someone could create a job with that previous experience and that background. Then we don't know, if it lasts for another thirty years, well ...

S.L. : It's many years, eh.

B.O. (Laughter) Yeah, looking at how the years were going in the 20th century and XXI.ean how they happen -- well, please. But, well, even if it's not thirty, there are fifteen -- something will be done.

How did Lander get to Rana, how did it happen?

B.O. : That will have to be told by him himself.

S.L. : I don't know very well [Javier laughs]. Because I started the year before in Istanbul. I spent half a year studying there and went back to Berlin on this topic of the pandemic. He had been in Berlin for ten years. Once there, and being in the houses closed, my sister told me that they were looking for someone in the Igela. Imagine, I am not a translator, I have never translated anything and if I have returned it has been bad...

B.O. : But if you have the opportunity to be a good entrepreneur [barriers].

S.L. : And that, in our family, there have never been entrepreneurs. Nobody, more is the master family. But I already had in mind to come back here, and I thought it would be better to come back with a job that I could and also I was very interested in. What especially influenced me was that the year before the arrival [Bernardo] I had to return to the German Obabakoak of Atxaga for a play that went from Bilbao to Stuttgart. Then in Berlin I have an intimate friend Irati Elorrieta and he had a book [Winter Lights], and there we were working almost two years, last year he won the Euskadi Prize. I cheered. I thought, “There will be lists and there will be people, and I will do it a bit like in Euskal Herria, not like in Europe.” I sent neither resume nor anything, I sent a letter saying “I am and I have done this and now I am going back, and if you want me already prepared”, and I don’t know, I have entered. I do not want to know who has not entered.

Has there been a significant change in the operation of the company?

S.L. : Well, I don't know the above, how they worked, but I do notice it, not only that in Igela, in many other parts of the Basque culture there has also been that jump, from the militancy ... I don't know how to call the second phase.

B.O. : Professionalization.

S.L. Yes. But at the same time, there's a generation that's been working quite precarious. I've been a Berlin waitress all the time studying, because I've painted the houses. So that life experience is very different. Today, things cannot be done as before in many ways. For example, because you are asked for bills everywhere, or because it is not as quiet as before, you have to be on the networks, after a month a book is no longer new... In this sense we will not work more than the previous generation, nor will the effort be the same, but it is necessary to adapt the heritage of the Frog to the current situation, not only to save, but to continue to bear fruit. I am also studying, every week giving Xabier and with the help of Fernando Rey a “turra”, and I am talking to a lot of people. Basically that is: you have to know the reader, the bookstore, the printing press, very important, the distributor... And without fear of making mistakes, because I've realized it's not an ideal process and it's quite difficult to get the perfect book out. At the moment, we have not suffered major blows, but well, we have been in the process for six months. Very bad books and also good books will come.

To what extent has the picture changed over the last thirty years?

B.O. : The Basque literature could have almost absolute control of all the works published in the 1980s. Still in the 1990s, and that stayed until the year 2000, I would say. Since then, things have changed a lot. You don't even know what comes out.

S.L. : I believe that both the authors and many people in the sector who move around the book have the potential of Christ, and that we should not be afraid to do difficult things. Look, the revolutionary thing was to attach so much importance to translation almost thirty-three years ago. In the catalogue of the frog there is an immense quality, and I believe that the issue must continue, that certain titles that today seem difficult to sell will be grateful to the Basque reader. That's why we're going to keep on with it, especially by taking out and trying to get more of a piece from each author, not only by bringing the books to Euskera, as a dead thing, as if it were a classic, but by bringing a piece that affects today's readers. Even now we are aware of the importance of translation, and it is late, but we are always on time. Until now, the translation has been widely enjoyed as a reader, and it has not been given as much importance in education and on the road the Basque needs. I hope that more will be introduced in education and in the Basque literature will also be given greater centrality, because the level of translators is impressive, and the level of the books that are brought, I believe.

Is the publication of literature translated into Basque a disgraceful work? Is it given the importance it deserves?

B.O. : That's always the war, and if we've been in that war for 30 years. For our part, the wager was clear from the beginning, and we have occasionally taken some extremes. It wouldn't be the same thing that the Rana had a line of textbooks coming out of there and then spending on literature I don't know what wagering on. But that is not the case and we have to be much more careful when choosing the works. In education, at least in part, it is clear that we have managed to introduce our books, both from the Black Section and from Agatha Christie, for example, which have been read frankly among teenagers. If there is a desire to move forward, there are some treasures that you can taste. That's the bet. Maybe they need another thirty years, I don't know.

S.L. : Poorly thanked, equally, by the institutions. Because translation has not been given proper centrality. But people moving in the book sector tend to criticize the reader, so I've seen in these six months: not selling enough, not reading enough, etc. That seems to me to be wrong. Because, on the one hand, people read what they want and what they want, and that happens everywhere and it's not going to change. On the other hand, if you want people to read more, you have to offer something better. In Euskal Herria, indeed, there is an audience that buys fairly militarily books in Euskera, at least from Basque writers, just as much translations, but I don't think the problem is people. What is more, the cultural position given to translation and the impetus given by those responsible for it. Not to create a raft of classics, but to complete the competences that the Basque country needs and that the Basque culture can achieve. Bringing to our world works by authors from all over the world is not something stagnant, but a concrete part of the Basque literature; the Basque is growing enormously, as the unified Basque did, it is, in short, a way to create more complete things.

So, I do not believe that the public is ungrateful, more so for the administration, and that is that there are subsidies and without those subsidies we could not make progress. It is not a question of money, but an idea of translation. If not, at the trade shows, people, and especially many adults, laugh at Agatha Christie being in Basque, as if it were absurd. This is not the fault of what you read, but the place where the media, the institutions, etc. You put the translation in.

B.O. Yes, that's true. But, well, we've been in that war for 30 years, and I think the situation has improved. You can't compare the echo of those books that we published at the beginning with the one that they've had afterwards.

S.L. : In the end, the literature or book sector is linked to society. In Euskal Herria we have been immersed in our wars, where the Basque writer has highlighted more. Now, for better or for worse, it's different, the question is changing. Being a more normal people, without positive or negative burdens, implies that in other places the type of market, the type of audience, the type of reader, etc. already existed. What we are in favour of is that those who have gone there and those who are now very good, that the sector is not unassembled. There are many good translators, and they are also increasingly specialized in languages. Little fear in this regard.

B.O. : At that time, at first, we were looking for people to translate the books, and the most reliable people were very busy. When you make an approach like the one we had now, you know that without much effort you will find those who will bring those texts right. That has changed.

The initial plan of the frog was to publish a hundred books in ten years.

B.O. But it cost us twice as much! What I came up with was that instead of taking a book out of each author, three had to be taken out. So, with 33 authors, 99 books came out, with the hundredth I don't know what we were going to do.

What is left of this plan today and what is the plan for the future?

B.O. : In the Black Section we have 25 of every 100 books left, but there are repeated authors. So if you want to follow that path, you would have to look up to 33 other six or seven authors and follow them, that would be possible. We didn't have any plans at the Literature Department. We knew roughly what kind of books we wanted to bring, Truman Capote, [Louis Ferdinand] the journey to the end of Céline Night, and many more. We have been completing and innovating, providing modern classics and no more new books: Annie Ernaux, Amélie Nothomb, [Alessandro] Baricco, [Natalia] Geneva... We've come a longer path if we have 61 to 62 titles, and the path is easier to reach 100. There is a kind of line, and now that times have changed so much, you could complete that journey and follow other paths. We walk with our mentality and with our idea in thirty years trying to do something and now we have to do something else. This corresponds to the new editor.

S.L. : I do not dare to make a plan of a hundred titles at all, but I do see that the principal treasure of the Frog is its catalogue. It's a very small but dignified, very concrete editorial, and I think that should never be changed. The sections are quite well organized and if the Black Section is a little the flag of the Igela. If you take the titles there, you can make almost a list of the best titles in the history of the black novel. This is very difficult to do in other languages that are standardised. I mean, if nobody does, you have total freedom and you don't have competition, and that's a wonderful thing. Looking to the future, I think it's very interesting to bring an author and keep taking out more of his book. It is about exploring new paths in two authors and topics; the Black Section itself, for example, is composed of 25 books and all writers are men. This has changed a lot in recent years, for example, there are Scandinavians ...

B.O. : [Patricia] We also brought Highsmith.

S.L. : But Higsmith is so good that he's in the Literature Section.

B.O. : Because she didn't want to be a black novels writer, but a mainstream writer, so we got her out in the Literature Department.

S.L. : It was important for me to see how things have been done so far. The ones we have brought out in the last few months were already semi-related because they were translations that were in the process. Among those we are going to take from now on, for example, Ursula K. There's a science fiction book by Le Guin and [W.G.] Some sebalde. On the other hand, we will probably create a new section, the shortest text that emerged from texts related to literature and other areas such as journalism, history, philosophy, etc., but which has had a literary life, in which, for example, we will publish the eighteenth part of the Brumario of [Karl] Marx, of Louis Bonaparte. But this collection may include an essay from Virginia Woolf or something from Walter Benjamin. There are many authors to bring. But don't rush, because I see that the easiest and most beautiful thing is to always make lists of books [Xabier laughs], what it brings, who it's going to bring, etc., and the hardest thing is to get the rights of the book, translate it, assemble everything and then sell it.

1959an publikatu zen literatura galiziarra astindu zuen nobela hau, baina duela gutxi arte ez dugu euskaraz irakurtzerik izan, Ramon Etxezarretaren itzulpena 2015ean argitaratu baitu Igelak.

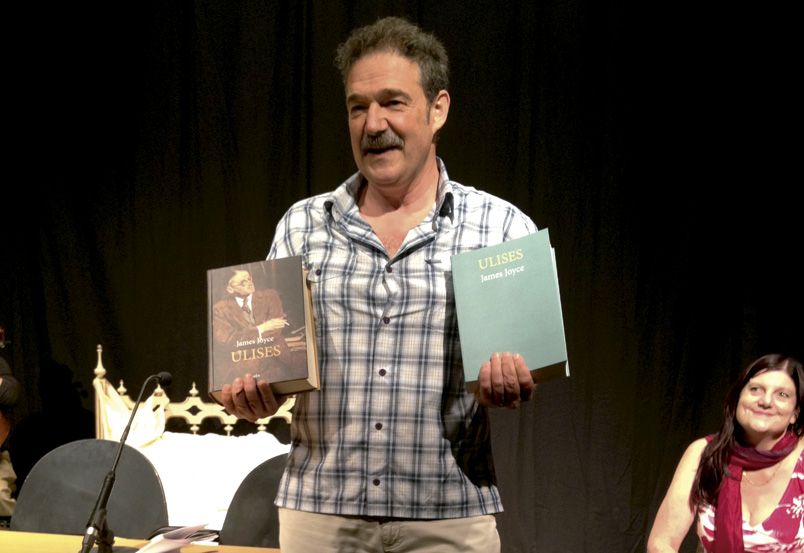

We already have Ulysses in Basque by James Joyce. On September 7, the editorial Igela presented the translation of the work considered the summit of 20th century literature. Xabier Olarra has done so and, given the peculiarities and difficulties of the text, it seems that it... [+]

Badaukagu James Joyceren Ulises euskaraz. Astelehen goizean aurkeztu du Igela argitaletxeak XX. mendeko literaturaren gailurtzat jotzen den obraren itzulpena. Xabier Olarrak egin du eta, testuaren berezitasun eta zailtasunak kontuan izanda, euskarazko itzulpengintza literarioan... [+]

Road to the city

Natalia Ginzburg

Translation: Pinch Lizarralde

Rana, 2001

“It is often said that the house where there are many children is joyful, but I found nothing of joy in ours.” Delia is the one who speaks that way. A 17-year-old girl. The second of five siblings... [+]

2014ko Nobel Saria Patrick Modianorentzat izango dela jakin eta biharamunean, haren obretako bat, Udaberri alua, frantsesetik euskarara itzuli duen Pello Lizarralderekin hitz egin du Natxo Velezek EITBren webgunean (euskaraz dagoen beste liburua Villa triste da eta Joseba... [+]

25 urteurrenera gazte eta berde iritsi da Igela argitaletxea. Nola lortu duten jakin nahian galdezka hasi garenean, Basic instinct filmeko Sharon Stonen gisa, lotsarik gabe erantzun digu Xabier Olarrak, Igelako editore, arduradun eta kulpante nagusiak.